Swami Vivekananda Prema Nandakumar ISBN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda

Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters (Fifth Series) Lectures and Discourses Notes of Lectures and Classes Writings: Prose and Poems (Original and Translated) Conversations and Interviews Excerpts from Sister Nivedita's Book Sayings and Utterances Newspaper Reports Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters - Fifth Series I Sir II Sir III Sir IV Balaram Babu V Tulsiram VI Sharat VII Mother VIII Mother IX Mother X Mother XI Mother XII Mother XIII Mother XIV Mother XV Mother XVI Mother XVII Mother XVIII Mother XIX Mother XX Mother XXI Mother XXII Mother XXIII Mother XXIV Mother XXV Mother XXVI Mother XXVII Mother XXVIII Mother XXIX Mother XXX Mother XXXI Mother XXXII Mother XXXIII Mother XXXIV Mother XXXV Mother XXXVI Mother XXXVII Mother XXXVIII Mother XXXIX Mother XL Mrs. Bull XLI Miss Thursby XLII Mother XLIII Mother XLIV Mother XLV Mother XLVI Mother XLVII Miss Thursby XLVIII Adhyapakji XLIX Mother L Mother LI Mother LII Mother LIII Mother LIV Mother LV Friend LVI Mother LVII Mother LVIII Sir LIX Mother LX Doctor LXI Mother— LXII Mother— LXIII Mother LXIV Mother— LXV Mother LXVI Mother— LXVII Friend LXVIII Mrs. G. W. Hale LXIX Christina LXX Mother— LXXI Sister Christine LXXII Isabelle McKindley LXXIII Christina LXXIV Christina LXXV Christina LXXVI Your Highness LXXVII Sir— LXXVIII Christina— LXXIX Mrs. Ole Bull LXXX Sir LXXXI Mrs. Bull LXXXII Mrs. Funkey LXXXIII Mrs. Bull LXXXIV Christina LXXXV Mrs. Bull— LXXXVI Miss Thursby LXXXVII Friend LXXXVIII Christina LXXXIX Mrs. Funkey XC Christina XCI Christina XCII Mrs. Bull— XCIII Sir XCIV Mrs. Bull— XCV Mother— XCVI Sir XCVII Mrs. -

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda India 2010 These precious memories of Swami Prabuddhanandaji are unedited. Since this collection is for private distribution, there has been no attempt to correct or standardize the grammar, punctuation, spelling or formatting. The charm is in their spontaneity and the heartfelt outpouring of appreciation and genuine love of this great soul. May they serve as an ongoing source of inspiration. Memories of Swami Prabuddhananda MEMORIES OF SWAMI PRABUDDHANANDA RAMAKRISHNA MATH Phone PBX: 033-2654- (The Headquarters) 1144/1180 P.O. BELUR MATH, DIST: FAX: 033-2654-4346 HOWRAH Email: [email protected] WEST BENGAL : 711202, INDIA Website: www.belurmath.org April 27, 2015 Dear Virajaprana, I am glad to receive your e-mail of April 24, 2015. Swami Prabuddhanandaji and myself met for the first time at the Belur Math in the year 1956 where both of us had come to receive our Brahmacharya-diksha—he from Bangalore and me from Bombay. Since then we had close connection with each other. We met again at the Belur Math in the year 1960 where we came for our Sannyasa-diksha from Most Revered Swami Sankaranandaji Maharaj. I admired his balanced approach to everything that had kept the San Francisco centre vibrant. In 2000 A.D. he had invited me to San Francisco to attend the Centenary Celebrations of the San Francisco centre. He took me also to Olema and other retreats on the occasion. Once he came just on a visit to meet the old Swami at the Belur Math. In sum, Swami Prabuddhanandaji was an asset to our Order, and his leaving us is a great loss. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

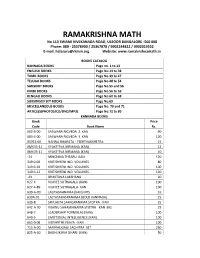

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi

american vedantist Volume 15 No. 3 • Fall 2009 Sri Sarada Devi’s house at Jayrambati (West Bengal, India), where she lived for most of her life/Alan Perry photo (2002) Used by permission Holy Mother, Sri Sarada Devi Vivekananda on The First Manifestation — Page 3 STATEMENT OF PURPOSE A NOTE TO OUR READERS American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is dedicated to developing VedantaVedanta in the West,West, es- American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is a not-for-profinot-for-profi t, quarterly journal staffedstaffed solely by pecially in the United States, and to making The Perennial Philosophy available volunteers. Vedanta West Communications Inc. publishes AV four times a year. to people who are not able to reach a Vedanta center. We are also dedicated We welcome from our readers personal essays, articles and poems related to to developing a closer community among Vedantists. spiritual life and the furtherance of Vedanta. All articles submitted must be typed We are committed to: and double-spaced. If quotations are given, be prepared to furnish sources. It • Stimulating inner growth through shared devotion to the ideals and practice is helpful to us if you accompany your typed material by a CD or fl oppy disk, of Vedanta with your text fi le in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Manuscripts also may • Encouraging critical discussion among Vedantists about how inner and outer be submitted by email to [email protected], as attached fi les (preferred) growth can be achieved or as part of the e mail message. • Exploring new ways in which Vedanta can be expressed in a Western Single copy price: $5, which includes U.S. -

—No Bleed Here— Swami Vivekananda and Asian Consciousness 23

Swami Vivekananda and Asian Consciousness Niraj Kumar wami Vivekananda should be credited of transformation into a great power. On the with inspiring intellectuals to work for other hand, Asia emerged as the land of Bud Sand promote Asian integration. He dir dha. Edwin Arnold, who was then the principal ectly and indirectly influenced most of the early of Deccan College, Pune, wrote a biographical proponents of panAsianism. Okakura, Tagore, work on Buddha in verse titled Light of Asia in Sri Aurobindo, and Benoy Sarkar owe much to 1879. Buddha stirred Western imagination. The Swamiji for their panAsian views. book attracted Western intellectuals towards Swamiji’s marvellous and enthralling speech Buddhism. German philosophers like Arthur at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche saw Bud on 11 September 1893 and his subsequent popu dhism as the world religion. larity in the West and India moulded him into a Swamiji also fulfilled the expectations of spokesman for Asiatic civilization. Transcendentalists across the West. He did not Huston Smith, the renowned author of The limit himself merely to Hinduism; he spoke World’s Religions, which sold over two million about Buddhism at length during his Chicago copies, views Swamiji as the representative of the addresses. He devoted a complete speech to East. He states: ‘Buddhism, the Fulfilment of Hinduism’ on 26 Spiritually speaking, Vivekananda’s words and September 1893 and stated: ‘I repeat, Shakya presence at the 1893 World Parliament of Re Muni came not to destroy, but he was the fulfil ligions brought Asia to the West decisively. -

The Chronology of Swami Vivekananda in the West

HOW TO USE THE CHRONOLOGY This chronology is a day-by-day record of the life of Swami Viveka- Alphabetical (master list arranged alphabetically) nanda—his activites, as well as the people he met—from July 1893 People of Note (well-known people he came in to December 1900. To find his activities for a certain date, click on contact with) the year in the table of contents and scroll to the month and day. If People by events (arranged by the events they at- you are looking for a person that may have had an association with tended) Swami Vivekananda, section four lists all known contacts. Use the People by vocation (listed by their vocation) search function in the Edit menu to look up a place. Section V: Photographs The online version includes the following sections: Archival photographs of the places where Swami Vivekananda visited. Section l: Source Abbreviations A key to the abbreviations used in the main body of the chronology. Section V|: Bibliography A list of references used to compile this chronol- Section ll: Dates ogy. This is the body of the chronology. For each day, the following infor- mation was recorded: ABOUT THE RESEARCHERS Location (city/state/country) Lodging (where he stayed) This chronological record of Swami Vivekananda Hosts in the West was compiled and edited by Terrance Lectures/Talks/Classes Hohner and Carolyn Kenny (Amala) of the Vedan- Letters written ta Society of Portland. They worked diligently for Special events/persons many years culling the information from various Additional information sources, primarily Marie Louise Burke’s 6-volume Source reference for information set, Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discov- eries. -

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda Swami Vivekananda (Bengali: [ʃami bibekanɔndo] ( listen); 12 January 1863 – 4 Swami Vivekananda July 1902), born Narendranath Datta (Bengali: [nɔrendronatʰ dɔto]), was an Indian Hindu monk, a chief disciple of the 19th-century Indian mystic Ramakrishna.[4][5] He was a key figure in the introduction of the Indian philosophies of Vedanta and Yoga to the Western world[6][7] and is credited with raising interfaith awareness, bringing Hinduism to the status of a major world religion during the late 19th century.[8] He was a major force in the revival of Hinduism in India, and contributed to the concept of nationalism in colonial India.[9] Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission.[7] He is perhaps best known for his speech which began, "Sisters and brothers of America ...,"[10] in which he introduced Hinduism at the Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago in 1893. Born into an aristocratic Bengali Kayastha family of Calcutta, Vivekananda was inclined towards spirituality. He was influenced by his guru, Ramakrishna, from whom he learnt that all living beings were an embodiment of the divine self; therefore, service to God could be rendered by service to mankind. After Vivekananda in Chicago, September Ramakrishna's death, Vivekananda toured the Indian subcontinent extensively and 1893. On the left, Vivekananda wrote: acquired first-hand knowledge of the conditions prevailing in British India. He "one infinite pure and holy – beyond later travelled to the United States, representing India at the 1893 Parliament of the thought beyond qualities I bow down World's Religions. Vivekananda conducted hundreds of public and private lectures to thee".[1] and classes, disseminating tenets of Hindu philosophy in the United States, Personal England and Europe. -

Swami Vivekananda's Devotion to His Mother Bhuvaneshwari Devi

Swami Vivekananda’s Devotion to His Mother Bhuvaneshwari Devi By Swami Tathagatananda The study of the cultural history of the world gives us an insight about the deep impact of religion on human development. Religious ideals, unflinching faith in divinity and a spiritual orientation permeate daily life. To understand a culture, we must evaluate the harmonious religious values of that culture. The English historian Christopher Dawson expressed this view: . throughout the greater part of mankind’s history, in all ages and states of society, religion has been the great unifying force in our culture. It has been the guardian of tradition, the preserver of the moral law, the educator and the teacher of wisdom. In all ages, the first creative works of a culture are due to a religious inspiration and dedicated to a religious end. The spiritual and ethical culture of any race preserves its noble characteristics. Swamiji says, “It is a change of the soul itself for the better that alone will cure the evils of life.” In his lecture, “The Future of India, Swamiji highlights the true role of culture: It is culture that withstands shocks, not a simple mass of knowledge. You can put a mass of knowledge into the world, but that will not do it much good. There must come culture into the blood. We all know in modern times of nations which have masses of knowledge, but what of them? They are like tigers, they are like savages, because culture is not there. Knowledge is only skin-deep, as civilization is, and a little scratch brings out the old savage. -

Hollywood Temple Santa Barbara Temple

HOLLYWOOD SANTA BARBARA RAMAKRISHNA TEMPLE TEMPLE MONASTERY ORANGE COUNTY 1946 Vedanta Place 927 Ladera Lane 19961 Live Oak Canyon Road Hollywood, CA 90068-3996 Santa Barbara, CA 93108 P.O. Box 408 323-465-7114 805-969-2903 Trabuco Canyon, CA 92678 949-858-0342 Temple Hours: 6:30 AM–7 PM Temple Hours: 6:30 AM–7 PM Visiting Hours: 9–11 AM, 3–5 PM FEBRUARY 2017 FEBRUARY 2017 FEBRUARY 2017 SUNDAY SPIRITUAL TALKS 11 AM SUNDAY SPIRITUAL TALKS 11 AM SUNDAY SPIRITUAL TALKS 11 AM Sunday School 11 AM–Noon, Ages 6–Teens 5 Swami Vedarupananda 5 Swami Yogeshananda 5 Swami Sarvadevananda The Practice of Contentment How God Speaks to Us Life After Death 12 Pravrajika Krishnaprana 12 Swami Sarvadevananda 12 Swami Vedarupananda Many Faces of Love Life After Death The Practice of Contentment 19 Swami Sarvadevananda 19 Swami Dhyanayogananda 19 Pravrajika Sevaprana Life After Death Beyond Life and Death Do You Feel for Others? 26 Swami Harinamananda 26 Swami Vedarupananda 26 Swami Mahayogananda Discovering Yourself The Practice of Contentment The Night of Shiva OTHER EVENTS WEEKLY CLASSES 7:30 PM OR AS NOTED OTHER EVENTS 4, 11 Saturday 5:30 PM Reading Wednesdays 7:30 PM Scripture Class Tuesday Katha Upanishad Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna 7, 14, 21, 28 Swami Sarvadevananda 6:30 PM Mahabharata at the Convent Wednesday Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna 1, 8, 15 Swami Sarvadevananda 18 Saturday 4:30 PM Class 22 Swami Atmatattwananda Nectar of Supreme Knowledge SAN DIEGO Thursday Pravrajika Sevaprana with Swami Sarvadevananda CENTER 2, 16 Vivekananda’s Inspired Talks 24 Friday 6–11:30 PM SHIVA RATRI Swami Vedarupananda 1440 Upas Street 9 Drugs, Hypnosis, and Spirituality 25 Saturday 10:30 AM–1 PM Retreat San Diego, CA 92103-5129 23 The Vision Quest with Swami Harinamanada 619-291-9377 Spiritual Café: Relationships Friday 3, 10, 17 Teachings of Ramakrishna’s Disciples Sign-up required: 805-969-5697 FEBRUARY 2017 Sundays 9–10:35 AM Sanskrit Class Bring Bag Lunch 28 Tues. -

Chicago Calling

CHICAGO CALLING A Spiritual & Cultural Quarterly eZine of the Vivekananda Vedanta Society of Chicago No. 27, 2020 Table of Contents Page EDITORIAL: BACK TO GOD 3 SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND SPIRITUAL RETREAT 5 SWAMI SARVADEVANANDA SANATANA DHARMA AND SPIRITUAL RETREAT 9 SWAMI BRAHMARUPANANDA GANGES RETREAT : AS WE SAW IT 11 DEVOTEES’ REMINISCENCES HISTORY OF GANGES 13 SWAMI VARADANANDA BHAGAVATA (2): RESPECTED RISHIS LEARN FROM A HUMBLE SUTA 15 SWAMI ISHATMANANDA INTRODUCTION TO THE COVER PAGE 17 ADVERTISEMENTS 28 Editor: Swami Ishatmananda Vivekananda Vedanta Society of Chicago 14630 Lemont Road, Homer Glen. 60491 email: [email protected] chicagovedanta.org ©Copyright: Swami-in-Charge Vivekananda Vedanta Society of Chicago NO 26, 2020 Chicago Calling 2 Editorial: BACK TO GOD One feeling is common in every human devotees to follow them also. Pilgrim centers like without any exception and that is dissatisfaction. Belur Math, Jayrambati (Holy Mother's birthplace) A king is dissatisfied because he can't become and Kamarpukur (Sri Ramakrishna's birthplace) an emperor, an emperor is dissatisfied because he have elaborate arrangements for the devotees. cannot rule the whole world. A singer is Most Vedanta Societies (Branches of the dissatisfied seeing the popularity of another singer. Ramakrishna Mission) in Northern America have A lady is dissatisfied seeing another lady wearing spiritual retreat centers. Devotees get both holy jewelry costlier than hers. Each and every human guidance and a secluded place to meditate on the is dissatisfied. ideals. Why this dissatisfaction? Is this a defect in the This year, 2020, on 11th September the human character? Vivekananda Vedanta Society of Chicago No. -

154Th Birthday Celebration Of

154th Birthday Celebration of 15th Inter School Quiz Contest – 2016 IMPORTANT & URGENT NOTE FOR THE KIND ATTENTION OF PRINCIPALS OF SCHOOLS Std. VII to Std. IX QUIZ PLEASE PHONE & CONFIRM IN WRITING THE NUMBER OF COPIES REQUIRED : 1) QUIZ BOOKLETS : To be given in advance to interested students. 2) QUIZ QUESTION : To be kept CONFIDENTIAL until the day of PAPERS the contest at school level. 3) ANSWER SHEET : For Correction RAMAKRISHNA MATH, 12th Road, Khar (West), Mumbai - 400 052. Ph : 6181 8000, 6182 8082, 6181 8002 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.rkmkhar.org Contents Unit 1: Multiple Choice Questions(50questions) Unit 2: Fill in the Blanks 2a. Swami Vivekananda’s Utterances by theme (24 questions) 2b. Utterances of Swami Vivekananda (13 questions) 2c. Life of Swami Vivekananda (26 questions) Unit 3: Choose any one option (10 questions) Unit 4: True or False 4a. From Swamiji’s life (11 questions) 4b. From Swamiji’s utterances (8 questions) Unit 5: Who said the following 5a. Who said the following to whom (5 questions) 5b. Who said the following (10 questions) Unit 6: Answer in one line (4 questions) Unit 7: Match the following (28 questions) 7a. Events and Dates from Swamiji’s first tour to the West 7b. Incidents that demonstrate Swami Vivekananda’s power of concentration 7c. The 4 locations of the Ramakrishna Math 7d. People in Swami Vivekananda’s life who helped him in bleak situations 7e. Events in Swamiji’s life with what we can learn from them 7f. Period of Swamiji’s life with events from his life Unit 8: Identify the Pictures (16 questions) Note: Any of the questions below can be asked in any other format also.