Meena Kandasamy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications MONOGRAPHS (MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE) Amrita Pritam (Punjabi writer) By Sutinder Singh Noor Pp. 96, Rs. 40 First Edition: 2010 ISBN 978-81-260-2757-6 Amritlal Nagar (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Narinder Bhullar Pp. 116, First Edition: 1996 ISBN 81-260-0088-0 Rs. 15 Baba Farid (Punjabi saint-poet) By Balwant Singh Anand Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 88, Reprint: 1995 Rs. 15 Balwant Gargi (Punjabi Playright) By Rawail Singh Pp. 88, Rs. 50 First Edition: 2013 ISBN: 978-81-260-4170-1 Bankim Chandra Chatterji (Bengali novelist) By S.C. Sengupta Translated by S. Soze Pp. 80, First Edition: 1985 Rs. 15 Banabhatta (Sanskrit poet) By K. Krishnamoorthy Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 96, First Edition: 1987 Rs. 15 Bhagwaticharan Verma (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Baldev Singh ‘Baddan’ Pp. 96, First Edition: 1992 ISBN 81-7201-379-5 Rs. 15 Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha (Punjabi scholar and lexicographer) By Paramjeet Verma Pp. 136, Rs. 50.00 First Edition: 2017 ISBN: 978-93-86771-56-8 Bhai Vir Singh (Punjabi poet) By Harbans Singh Translated by S.S. Narula Pp. 112, Rs. 15 Second Edition: 1995 Bharatendu Harishchandra (Hindi writer) By Madan Gopal Translated by Kuldeep Singh Pp. 56, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1984 Bharati (Tamil writer) By Prema Nand kumar Translated by Pravesh Sharma Pp. 103, Rs.50 First Edition: 2014 ISBN: 978-81-260-4291-3 Bhavabhuti (Sanskrit poet) By G.K. Bhat Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 80, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1983 Chandidas (Bengali poet) By Sukumar Sen Translated by Nirupama Kaur Pp. -

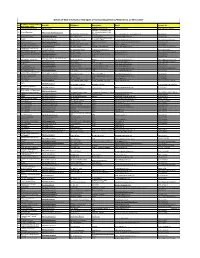

List of 253 Journalists Who Lost Their Lives Due to COVID-19. (Updated Until May 19, 2021)

List of 253 Journalists who lost their lives due to COVID-19. (Updated until May 19, 2021) Andhra Pradesh 1 Mr Srinivasa Rao Prajashakti Daily 2 Mr Surya Prakash Vikas Parvada 3 Mr M Parthasarathy CVR News Channel 4 Mr Narayanam Seshacharyulu Eenadu 5 Mr Chandrashekar Naidu NTV 6 Mr Ravindranath N Sandadi 7 Mr Gopi Yadav Tv9 Telugu 8 Mr P Tataiah -NA- 9 Mr Bhanu Prakash Rath Doordarshan 10 Mr Sumit Onka The Pioneer 11 Mr Gopi Sakshi Assam 12 Mr Golap Saikia All India Radio 13 Mr Jadu Chutia Moranhat Press club president 14 Mr Horen Borgohain Senior Journalist 15 Mr Shivacharan Kalita Senior Journalist 16 Mr Dhaneshwar Rabha Rural Reporter 17 Mr Ashim Dutta -NA- 18 Mr Aiyushman Dutta Freelance Bihar 19 Mr Krishna Mohan Sharma Times of India 20 Mr Ram Prakash Gupta Danik Jagran 21 Mr Arun Kumar Verma Prasar Bharti Chandigarh 22 Mr Davinder Pal Singh PTC News Chhattisgarh 23 Mr Pradeep Arya Journalist and Cartoonist 24 Mr Ganesh Tiwari Senior Journalist Delhi 25 Mr Kapil Datta Hindustan Times 26 Mr Yogesh Kumar Doordarshan 27 Mr Radhakrishna Muralidhar The Wire 28 Mr Ashish Yechury News Laundry 29 Mr Chanchal Pal Chauhan Times of India 30 Mr Manglesh Dabral Freelance 31 Mr Rajiv Katara Kadambini Magazine 32 Mr Vikas Sharma Republic Bharat 33 Mr Chandan Jaiswal Navodaya Times 34 Umashankar Sonthalia Fame India 35 Jarnail Singh Former Journalist 36 Sunil Jain Financial Express Page 1 of 6 Rate The Debate, Institute of Perception Studies H-10, Jangpura Extension, New Delhi – 110014 | www.ipsdelhi.org.in | [email protected] 37 Sudesh Vasudev -

The Social Context of Nature Conservation in Nepal 25 Michael Kollmair, Ulrike Müller-Böker and Reto Soliva

24 Spring 2003 EBHR EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH European Bulletin of Himalayan Research The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR) was founded by the late Richard Burghart in 1991 and has appeared twice yearly ever since. It is a product of collaboration and edited on a rotating basis between France (CNRS), Germany (South Asia Institute) and the UK (SOAS). Since October 2002 onwards, the German editorship has been run as a collective, presently including William S. Sax (managing editor), Martin Gaenszle, Elvira Graner, András Höfer, Axel Michaels, Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, Mona Schrempf and Claus Peter Zoller. We take the Himalayas to mean, the Karakorum, Hindukush, Ladakh, southern Tibet, Kashmir, north-west India, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and north-east India. The subjects we cover range from geography and economics to anthropology, sociology, philology, history, art history, and history of religions. In addition to scholarly articles, we publish book reviews, reports on research projects, information on Himalayan archives, news of forthcoming conferences, and funding opportunities. Manuscripts submitted are subject to a process of peer- review. Address for correspondence and submissions: European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, c/o Dept. of Anthropology South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University Im Neuenheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg / Germany e-mail: [email protected]; fax: (+49) 6221 54 8898 For subscription details (and downloadable subscription forms), see our website: http://ebhr.sai.uni-heidelberg.de or contact by e-mail: [email protected] Contributing editors: France: Marie Lecomte-Tilouine, Pascale Dollfus, Anne de Sales Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UPR 299 7, rue Guy Môquet 94801 Villejuif cedex France e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain: Michael Hutt, David Gellner, Ben Campbell School of Oriental and African Studies Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square London WC1H 0XG U.K. -

Jupiter Institute Current Affairs March 2019 E.Pdf

Jupiter Institute Current Affairs - March 2019 Table of Contents Current Affairs: Important Days ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Current Affairs: Appointments ......................................................................................................................................... 2 International Appointments: ........................................................................................................................................ 2 National Appointments: ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Current Affairs: Awards and Honours ............................................................................................................................... 3 Current Affairs: Banking and Finance ............................................................................................................................... 4 Current Affairs: Defence .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Current Affairs: Economic Affairs ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Current Affairs: International ..........................................................................................................................................11 -

Dr. Manmohan Singh a Fit Case for Impeachment B

Social Science in Perspective EDITORIAL BOARD Chairman & Editor-in-chief Prof. (Dr.) K. Raman Pillai Editor Dr. R.K. Suresh Kumar Executive Editor Dr. P. Sukumaran Nair Associate Editors Dr. P. Suresh Kumar Adv. K. Shaji Members Prof. Puthoor Balakrishnan Nair Prof. K. Asokan Prof.V. Sundaresan Shri. V. Dethan Shri. C.P. John Dr. Asha Krishnan Managing Editor Shri. N. Shanmughom Pillai Circulation Manager Shri. V.R. Janardhanan Published by C. ACHUTHA MENON STUDY CENTRE & LIBRARY Poojappura, Thiruvananthapuram - 695 012 Tel & Fax : 0471 - 2345850 Email : [email protected] www.achuthamenonfoundation.org ii INSTRUCTION TO AUTHORS / CONTRIBUTORS Social Science in Perspective,,, a peer reviewed journal, is the quarterly journal of C. Achutha Menon (Study Centre & Library) Foundation, Thiruvananthapuram. The journal appears in English and is published four times a year. The journal is meant to promote and assist basic and scientific studies in social sciences relevant to the problems confronting the Nation and to make available to the public the findings of such studies and research. Original, un-published research articles in English are invited for publication in the journal. Manuscripts for publication (articles, research papers, book reviews etc.) in about twenty (20) typed double-spaced pages may kindly be sent in duplicate along with a CD (MS Word). The name and address of the author should be mentioned in the title page. Tables, diagram etc. (if any) to be included in the paper should be given separately. An abstract of 50 words should also be included. References cited should be carried with in the text in parenthesis. Example (Desai 1976: 180) Bibliography, placed at the end of the text, must be complete in all respects. -

20Years of Sahmat.Pdf

SAHMAT – 20 Years 1 SAHMAT 20 YEARS 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements 2 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 YEARS, 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements © SAHMAT, 2009 ISBN: 978-81-86219-90-4 Rs. 250 Cover design: Ram Rahman Printed by: Creative Advertisers & Printers New Delhi Ph: 98110 04852 Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust 29 Ferozeshah Road New Delhi 110 001 Tel: (011) 2307 0787, 2338 1276 E-mail: [email protected] www.sahmat.org SAHMAT – 20 Years 3 4 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 Years 5 Safdar Hashmi 1954–1989 Twenty years ago, on 1 January 1989, Safdar Hashmi was fatally attacked in broad daylight while performing a street play in Sahibabad, a working-class area just outside Delhi. Political activist, actor, playwright and poet, Safdar had been deeply committed, like so many young men and women of his generation, to the anti-imperialist, secular and egalitarian values that were woven into the rich fabric of the nation’s liberation struggle. Safdar moved closer to the Left, eventually joining the CPI(M), to pursue his goal of being part of a social order worthy of a free people. Tragically, it would be of the manner of his death at the hands of a politically patronised mafia that would single him out. The spontaneous, nationwide wave of revulsion, grief and resistance aroused by his brutal murder transformed him into a powerful symbol of the very values that had been sought to be crushed by his death. Such a death belongs to the revolutionary martyr. 6 PUBLICATIONS Safdar was thirty-four years old when he died. -

Next 4 Weeks Crucial to Bring Down Covid Second Wave

Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 Established 1864 ANALYSIS 7 MONEY 8 SPORTS 12 Published From HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW GEOPOLITICS TRUMPS SURGE IN CORONAVIRUS CASES MAY CLINICAL CSK REGAIN BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH GEOECONOMICS PUT ECONOMIC RECOVERY AT RISK TOP SPOT BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN VIJAYAWADA *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 189 HYDERABAD, THURSDAY APRIL 29, 2021; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable PRABHAS-NAG ASHWIN FILM TO LAUNCH ON DIWALI { Page 11 } www.dailypioneer.com SONY'S PROFIT ZOOMS TO RECORD LEVEL US RUSHING ASSISTANCE TO INDIA TO MAHA GIVES RS 1,500 EACH TO 9.17 FOUR-DAY LOCKDOWN IN GOA FROM ON VIDEO GAMES, ‘DEMON SLAYER’ COMBAT COVID SURGE: JOE BIDEN LAKH CONSTRUCTION WORKERS TODAY AS CASES SPIKE: CM ony's January-March profit zoomed eight- ashington, Apr 28 (PTI) The US is rushing he Maharashtra government has transferred he Goa government on Wednesday fold to 107 billion yen (USD 982 million) a whole series of help, including life- Rs 1,500 in the bank accounts of each of decided to impose a strict lockdown Sfrom a year earlier as people stuck at Wsaving drugs and machinery, that India Tthe 9.17 lakh registered construction Tin the state beginning April 29 till home during the coronavirus pandemic needs to combat the massive surge in workers as assistance in view of the May 3, Chief Minister Pramod Sawant turned to the Japanese electronics and COVID-19 cases, President Joe Biden has COVID-19-induced restrictions, state said. Speaking to reporters, he said entertainment company's video games and said, as he again recalled New Delhi's Labour Minister Hasan Mushrif said on essential services and industries will other visual content. -

Details of Web Information Managers of Various Departments/Websites As on 06-11-2017

Details of Web Information Managers of Various Departments/Websites as on 06-11-2017 Department/Organization/ SR. No Site URL WIM Name Designation Email Contact No Directorate name 1 Uttarakhand State Portal http://uk.gov.in Additional Secretary(IT) as-it-ua[at]nic[dot]in 0135-2712013, 2708122 PROJECT CO-ORDINATOR, 2 School Education http://schooleducation.uk.gov.in UTTRAKHAND EDUCATION Mr. MUKESH BAHUGUNA PORTAL [email protected], [email protected] 9412029617 3 Budget Directorate http://budget.uk.gov.in Shri Amit Verma Research Officer [email protected] 135-2651822, Unit Coordinator (Monitoring & 4 Swajal http://swajal.uk.gov.in Mr. Sanjay Kumar Singh Evaluation / HRD) [email protected] 135-2643455,8191830001 5 Commercial Tax http://comtax.uk.gov.in Neelam Dhyani Deputy Commissioner neelam_baunthi[at]yahoo[dot]co[dot]in 0135-2654588 7 Stamps and Registration http://registration.uk.gov.in Shri Roop Narayan Sonkar AIG [email protected] 135-2669656, 8 State Election Commission http://sec.uk.gov.in Ms. Nidhi Rawat Assistant Commissioner [email protected] 135-2670457,9412969354 Uttarakhand Public Service 9 http://ukpsc.gov.in Commission Mr. Banshidhar Tiwari, Controller of Examination 91-01334-244677 10 Sarva Shiksha Abiyan http://ssa.uk.gov.in Sh. K.K. Gupta Expert PMIS [email protected] 135-2781943,9837205059 11 ACCOUNTANTS GENERAL http://agua.cag.gov.in Shri N.K. Dabral Deputy Accountant General [email protected] 0135-2644965 12 ITDA http://itda.uk.gov.in Ms. Rajni Joshi WIM 135-2708122, http://res.uk.gov.in, http://rwd.uk.gov.in 13 Rural Engineering Service (new address) Dr. -

GNP Or GNH: How Realistic Is the Choice? B.K

hi adri 4 D O O N L I B R A R Y June, 2010 & R e s e a r c h C e n t r e GNP or GNH: How realistic is the choice? B.K. Joshi n a recent issue of the Nepali programmes within the nationally and procedures. Unfortunately, it ITimes1, Artha Beed2 has written determined framework. remains a fact that the notion of a thought-provoking column titled GNH as distinguished from GNP is “Himalayan experiments: Can Bhutan The choice, however, is not an easy nowhere on the horizon of possible get it right?” Based on his recent visit one. It would, in fact, mean turning options in India today. No political to Bhutan he says: “The Bhutanese our back on many of the conveniences party has espoused the idea as talk extensively about Gross National that we now take for granted and evidenced by their manifestoes in Happiness (GNH) as a counter to are becoming increasingly addicted the last parliamentary election; market and consumption driven to. These would doubtless include neither does it figure in academic GDP. For instance, mountaineering in the private car/motor cycle/scooter, debates and discussions. On the Bhutan is not allowed, as it has been internet, cable or dish television and contrary a wide consensus seems to deemed that the mountains should mobile phone to name just a few. exist in the country on the notion of be kept as they are. Their conception Artha Beed poses these questions in inclusive growth. The issue therefore of measuring people's happiness the context of Bhutan in the following is can and should the notion of Gross as opposed to consumption or words: National Happiness become the production is unique, and is a counter “While a small population can allow new orthodoxy in development? Is it to western measures of prosperity.” for Singapore-style governance and desirable? Is it possible? If so how? We feel that this sentiment will control, the opening up of information We are posing this question with find resonance in many people access will be difficult to stem. -

Syllabi for Common Course in Hindi for Model I BA/Bsc/Bcom and Model II Programmes Under Credit Semester System (With Effect from 2019 Admissions)

DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL LANGUAGES Syllabi for Common Course in Hindi for Model I BA/BSc/BCom and Model II Programmes Under Credit Semester System (with effect from 2019 admissions) Expert Committee in Hindi 1. Dr. Jyothi Balakrishnan (External Expert) (Asso. Professor & Head, P.G. & Research Dept. of Hindi, N.S.S. Hindu College, Changanassery) 2. Dr. Issac K. S. (Member) (Asso. Professor, Dept. of Hindi, S.B. College, Changanassery) 3. Dr. Mathew Abraham (Member) (Asso. Professor, Dept. of Hindi, S.B. College, Changanassery) 4. Dr. Roy Joseph (Chairman) (Asso. Professor & Head, Dept. of Hindi, S.B. College, Changanassery) Decisions of the Expert Committee held on 1-11-2018 Subject: Common Course Hindi It has been decided to restructure and modify the syllabus for the Common Course in Hindi in St. Berchmans College, Changanassery from June 2019 onwards. The modification and minor changes that have been brought in are in conformity with the broader aims and objectives stipulated by the Mahatma Gandhi University. The pattern of the redesigned curriculum for BA/BSc/BCom and BA English Model II is as follows: BA/BSc Degree Programme 1. Semester – I Prose and One Act Plays (BCHB101) 4 Hrs (Credit - 4) 2. Semester – II Short Stories and Novel (BCHB202) 4 Hrs (Credit - 4) 3. Semester – III Poetry, Grammar and Translation (BCHB303) 5 Hrs (Credit - 4) 4. Semester – IV Drama and Long Poem (BCHB404) 5 Hrs (Credit - 4) BCom Degree Programme 1. Semester – I Prose and Mass Media (BCHC101) 4 Hrs (Credit - 4) 2. Semester – II Poetry, Commercial Correspondence and Translation (BCHC202) 4 Hrs (Credit - 4) BA English Model II English Common Course Hindi 1. -

Geographies That Make Resistance”: Remapping the Politics of Gender and Place in Uttarakhand, India

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 34 Number 1 Article 12 Spring 2014 Geographies that Make Resistance”: Remapping the Politics of Gender and Place in Uttarakhand, India Shubhra Gururani York University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Gururani, Shubhra. 2014. Geographies that Make Resistance”: Remapping the Politics of Gender and Place in Uttarakhand, India. HIMALAYA 34(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol34/iss1/12 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Geographies that Make Resistance”: Remapping the Politics of Gender and Place in Uttarakhand, India Acknowledgements I would like to profusely thank the women who openly and patiently responded to my inquiries and encouraged me to write about their struggle and their lives. My thanks also to Kim Berry, Uma Bhatt, Rebecca Klenk, Manisha Lal, and Shekhar Pathak for reading and commenting earlier drafts of the paper. This research article is available in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and -

Festival of Letters 2014

DELHI Festival of Letters 2014 Conglemeration of Writers Festival of Letters 2014 (Sahityotsav) was organised in Delhi on a grand scale from 10-15 March 2014 at a few venues, Meghadoot Theatre Complex, Kamani Auditorium and Rabindra Bhawan lawns and Sahitya Akademi auditorium. It is the only inclusive literary festival in the country that truly represents 24 Indian languages and literature in India. Festival of Letters 2014 sought to reach out to the writers of all age groups across the country. Noteworthy feature of this year was a massive ‘Akademi Exhibition’ with rare collage of photographs and texts depicting the journey of the Akademi in the last 60 years. Felicitation of Sahitya Akademi Fellows was held as a part of the celebration of the jubilee year. The events of the festival included Sahitya Akademi Award Presentation Ceremony, Writers’ Meet, Samvatsar and Foundation Day Lectures, Face to Face programmmes, Live Performances of Artists (Loka: The Many Voices), Purvottari: Northern and North-Eastern Writers’ Meet, Felicitation of Akademi Fellows, Young Poets’ Meet, Bal Sahiti: Spin-A-Tale and a National Seminar on ‘Literary Criticism Today: Text, Trends and Issues’. n exhibition depicting the epochs Adown its journey of 60 years of its establishment organised at Rabindra Bhawan lawns, New Delhi was inaugurated on 10 March 2014. Nabneeta Debsen, a leading Bengali writer inaugurated the exhibition in the presence of Akademi President Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari, veteran Hindi poet, its Vice-President Chandrasekhar Kambar, veteran Kannada writer, the members of the Akademi General Council, the media persons and the writers and readers from Indian literary feternity.