Vasudha Pande.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley Room One Thousand

UC Berkeley Room One Thousand Title Kingship, Buddhism and the Forging of a Region Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8vn4g2jd Journal Room One Thousand, 3(3) ISSN 2328-4161 Author Hawkes, Jason Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Jason Hawkes Kingship, Buddhism and the MedievalForging Pilgrimage of a inRegion West Nepal West Nepal provides a unique space to think about pilgrimage in the past. For many centuries, this central Himalayan region lay at the fringes of neighboring states. During the 13th century CE, the Khasa Malla dynasty established a kingdom here with seasonal capitals at Sinja and Dullu, which soon grew to encompass the entire region as well as parts of India and Tibet (Adhikary 1997; Pandey 1997) (Figure 1). With these developments, the region became a key zone of interaction. Capitalizing on pre-existing routes and connections, it connected India to the Silk Road, and provided a conduit for the spread and survival of Indian Buddhism. Pilgrimage would have been an important component of the movement of people and ideas within and across the region— interactions that shaped the socio-cultural and economic dynamics of the area. However, due to its liminal position, the study of West Nepal has been neglected in favor of more ‘important’ neighboring regions. As such, we have only n outline understanding of pilgrimage and the societal framework within which it took place. The monuments built during the reign of the Khasa Malla provide tantalizing clues that can be used to study pilgrimage and the movement Figure 1 243 Jason Hawkes of people and ideas in the Himalaya. -

Faculty Profile

Format-II FACULTY PROFILE 1. Name: Dr. SHOBHA RAWAT 2. Designation: ASSISTANT PROFESSOR (Guest Faculty) 3. Qualification: M. Sc. BOTANT, Ph. D 4. Area of Specialization/Research field: LICHENOLOGY 5. Awards/Recognitions: RGNF- JRF (2007) RGNF- SRF (2009) UGC-POST DOCTORAL FELLOW (2012) 6. Number of Research projects: 01 i) Completed Sl. No. Title of the project Funding Agency Amount(Rs.) Year (From-To) 1 UGC- (PDF) UGC 18,75, 883 Rs. 2012-2017 ii) On-going: NA 7. Number of Ph. D candidates successfully completed: NO 8. Number of Ph. D candidates currently working: NO 9. Publications: 20 i) Books: NO ii) Research Articles published in journals 1. Rawat, S., Upreti, D. K. and Singh, R. P. (2009). Lichen flora of Mandal and adjoining localities towards Ukhimath in Chamoli district of Uttarakhand. Journal of Phytological Research 22 (1) 47-52. ISSN: 0970-5767. 2. Rawat, S., Upreti, D. K. and Singh, R. P. (2010). Lichen diversity in Valley of Flowers National Park Western Himalaya, Uttarakhand, India. Phytotaxonomy 10 112-117. ISSN 0972-4206. 3. Rawat, S., Upreti, D. K. and P. K. Divakar (2011). Xanthoparmelia xizangensis (J. C. Wei) Hale, a new record of lichen from India. Geophytology 41 (1-2) 101- 103. ISSN 0376-5561. 4. Rawat, S., Upreti, D. K. and Singh, R. P., (2011). Estimation of epiphytic lichen litter fall biomass in three temperate forests of Chamoli district, Uttarakhand, India. International Society for Tropical Ecology 52 (2) 193-200. ISSN 0564-3295 5. Rawat, S., Singh, R. P. Upreti, D. K., (2013). Lichen Diversity Of Durmi Forest In Chamoli District, Uttarakhand, Journal Of Economic and Taxonomic Botany, 37(2), 223. -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

Appendix 5A – Consultations the List Includes Stakeholders Interviewed During the Inception and Field Phase of the Joint Evaluation

Joint Evaluation of the Secondary Education Support Programme Appendix 5a – Consultations The list includes stakeholders interviewed during the inception and field phase of the joint evaluation. In addition, the joint evaluation has benefited from feedback made by participants at the inception seminar and the seminar arranged to present the draft report. These included government officials, researchers, peer reviewers, civil society representatives and development partners. Appendix 5b has details on stakeholders consulted at districts and school level. Name Position Institution 1. Arjun Bahadur Bhandari Joint Secretary MoE 2. Janardhan Nepal Joint Secretary 3. Dr. Lava Deo Awasthi Joint Secretary 4. Bharat Nepali Pyakurel Under Secretary School Inspectorate, MoE 5. Ram Bahadur Khadka Section Officer 6. Ms. Usha Paudel (Kandel) Section Officer 7. Gopal Prasad Bhandari Section Officer 8. Nakul Baniya Section Officer Policy Analysis & Planning 9. Pralhad Aryal Section Officer Section, MOE 10. Deepak Sharma Under Secretary 11. Geha Nath Gautam Section Officer Planning Section, MoE 12. Narayan K Shrestha Section Officer Foreign Aid Coordination 13. Indra Bahadur Kunwar Section Officer Section (FACS), MOE 14. Mukunda Khanal Section Officer 15. Lesha Nath Poudel Under Secretary 16. Subhadra Kumari RC Thapa Under Secretary 17. Frank Jensen Chief Technical Adviser Education Sector Advisory Team / MoE 18. Mahashram Sharma Director General DoE 19. Chudamani Poudel Section Chief Gender Equity Section, DOE 20. Damodar Regmi Section Officer 21. Dibya Dawadi Section Officer 22. Kamala Gyawali Section Officer 23. Ram Hari Rijal 24. Arun Tiwari Section Chief Inclusive Education Section, 25. Ganesh Poudel Section Officer DOE 26. Narayan Subedi Section Officer 27. Kumar Bhattarai Section Officer 28. -

Kumaun Histories and Kumauni Identities C.1815–1990'S

Research Articles Kumaun Histories and Kumauni Identities c.1815–1990’s Vasudha Pande* The emergence of ‘History’ as a practice and as a fauna, geography, religious beliefs and caste practices. discipline, which transformed inherited oral traditions Atkinson’s understanding of the history of the region into textual products, has to be located in the modern was foundational and continues to resonate in histories of period.1I. Chambers says that history transcribed all Kumaun even today. It may be summarised as follows:- human practice- ‘it registered, transmitted and translated the original residents of the hills were the Dasyus, also the past, and it reordered and rewrote the world.’2The referred to as Doms, (aboriginal) ‘the Doms in the hills discipline, as it emerged in Europe, was predicated are not a local race peculiar to Kumaun, but the remains upon an understanding of the past as a period when of an aboriginal tribe conquered and enslaved by the men were not free, whereas the ‘modern’ present was immigrant Khasas.’7The Khasas were of, ‘an Aryan considered emancipatory because in modernity, ‘identity descent in the widest sense of that term much modified becomes more mobile, multiple, personal, self-reflexive by local influences, but whether they are to be attributed and subject to change and innovation.’3 The modern was to the Vedic immigration itself or to an earlier or later therefore understood as rupture, which made the writing movement of tribes having a similar origin, there is little of history possible.4 The extension of this project to the to show. It is probable, however, that they belong to a colonies also generated a history of the colonial peoples. -

R&D-FIAN Parallel Information Nepal

Reference: The Second Periodic Report (Art.1-15) of Nepal to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UN Doc. E/C.12/NPL/2) Parallel Information The Right to Adequate Food in Nepal (Article 11, ICESCR) Submitted at the occasion of the 38th session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (30 April - May 2007) by FIAN International, an NGO in consultative status with ECOSOC, working for the right to feed oneself and Rights & Democracy, a Canadian institution in consultative status with ECOSOC working to promote the International Bill of Human Rights. - 1 - Table of Contents I. Preliminary remarks p.3 II. The situation of the Right to Food in Nepal p.4 III. Legal Framework of the Right to Food in Nepal p.16 IV. Illustrative cases of violations of the Right to Food p.22 V. Concluding remarks p.27 VI. Recommendations to the CESCR p.28 Annex I - Description of the International Fact-Finding Mission p.29 Annex II - List of Acronyms p.37 - 2 - I. Preliminary remarks The present document is presented to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights as parallel information to the second periodic report of Nepal to the CESCR. The submitting organizations would like to acknowledge the opportunity given by the CESCR procedures and share with the Committee the first findings of two research projects which have been carried out by Rights & Democracy and FIAN International. 1. The Fact-Finding Mission to Nepal (coordinated by Rights & Democracy) The first measure is the Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) which took place from 8 to 20 April 2007 and was organized by the Canadian institution Rights & Democracy in collaboration with the Right to Food Research Unit at the University of Geneva, FIAN International and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). -

November, 1989

Regmi Research (Private) Ltd. ISSN: 0034-348X Re i Research Series �ear 21 , No • 11 Kathmandu . November. 1989 Edited By Mahesh· C. Regmi Contents Page 1 • The Jaisi Caste . 151 2. Miscellaneous Royal Orders . 156 3. Trade Between British India. and Nepal . .. 160 ********* Regmi Resea'r�ch (Private) Ltd. Lazimpat, Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: 4-11927 (For private study and research only; not meant for public sale, distribution and display). 151 The Jaisi Caste Previous References: 1. "The ,Jaisi Caste", Regmi Research Series, Year 2, No. 12, December 1, 1970, pp. 277-85. 2. "Upadhyaya Brahmans and Jaisis", Regmi Research Series, Year, 18, No. 5, May 19 81 , pp • 77-78. Public Notification: The following public notification was issued under the rQyal seal on Marga. Badi 3, 1856 for the following regions: (1) Dudhkosi-Arun region ( 2) Patan town (3) Rural areas of Pa.tan (4) Chepe/Narsyangdi-Gandi region (5) Pallokira.t region, east of the Arun river (6) Kali/Modi-Bheri region (7) Chepe/Marsyangdi-Kali/N.o�i region (8) Kathmandu town (9) Bhadgaun town (10) Rural areas of Bhadgaun (11) Trishuli-Gandi region (12) Tamakosi-Dudhkosi region (13) Sindhu-Tamakosi region. "You Jaisis are sons of whores. Our great-grandfather (i. e. King Prithvi Narayan Shah) had promulgated regulations prohibiting you from engaging in priestly (swa.ha., swadha) functions, and offering blessiilP'S (ashish) and greetings (Pranama), and ordering you to offer salnams instead. However, you have acted in contravention of those regulations. We accordingly punish you with fines as follows. Pay the fines to the men we have sent to collect them. -

VBST Short List

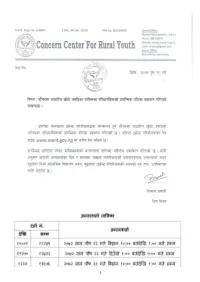

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

The Social Context of Nature Conservation in Nepal 25 Michael Kollmair, Ulrike Müller-Böker and Reto Soliva

24 Spring 2003 EBHR EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH European Bulletin of Himalayan Research The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR) was founded by the late Richard Burghart in 1991 and has appeared twice yearly ever since. It is a product of collaboration and edited on a rotating basis between France (CNRS), Germany (South Asia Institute) and the UK (SOAS). Since October 2002 onwards, the German editorship has been run as a collective, presently including William S. Sax (managing editor), Martin Gaenszle, Elvira Graner, András Höfer, Axel Michaels, Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, Mona Schrempf and Claus Peter Zoller. We take the Himalayas to mean, the Karakorum, Hindukush, Ladakh, southern Tibet, Kashmir, north-west India, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and north-east India. The subjects we cover range from geography and economics to anthropology, sociology, philology, history, art history, and history of religions. In addition to scholarly articles, we publish book reviews, reports on research projects, information on Himalayan archives, news of forthcoming conferences, and funding opportunities. Manuscripts submitted are subject to a process of peer- review. Address for correspondence and submissions: European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, c/o Dept. of Anthropology South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University Im Neuenheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg / Germany e-mail: [email protected]; fax: (+49) 6221 54 8898 For subscription details (and downloadable subscription forms), see our website: http://ebhr.sai.uni-heidelberg.de or contact by e-mail: [email protected] Contributing editors: France: Marie Lecomte-Tilouine, Pascale Dollfus, Anne de Sales Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UPR 299 7, rue Guy Môquet 94801 Villejuif cedex France e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain: Michael Hutt, David Gellner, Ben Campbell School of Oriental and African Studies Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square London WC1H 0XG U.K. -

Four Ana and One Modem House: a Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery

I Four Ana and One Modem House: A Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery Andrew Stephen Nelson Denton, Texas M.A. University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, December 2004 B.A. Grinnell College, December 2000 A Disse11ation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Virginia May 2013 II Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: An Intellectual Journey to the Urban Periphery 1 Part I: The Alienation of Farm Land 23 Chapter 2: From Newar Urbanism to Nepali Suburbanism: 27 A Social History of Kathmandu’s Sprawl Chapter 3: Jyāpu Farmers, Dalāl Land Pimps, and Housing Companies: 58 Land in a Time of Urbanization Part II: The Householder’s Burden 88 Chapter 4: Fixity within Mobility: 91 Relocating to the Urban Periphery and Beyond Chapter 5: American Apartments, Bihar Boxes, and a Neo-Newari 122 Renaissance: the Dual Logic of New Kathmandu Houses Part III: The Anxiety of Living amongst Strangers 167 Chapter 6: Becoming a ‘Social’ Neighbor: 171 Ethnicity and the Construction of the Moral Community Chapter 7: Searching for the State in the Urban Periphery: 202 The Local Politics of Public and Private Infrastructure Epilogue 229 Appendices 237 Bibliography 242 III Abstract This dissertation concerns the relationship between the rapid transformation of Kathmandu Valley’s urban periphery and the social relations of post-insurgency Nepal. Starting in the 1970s, and rapidly increasing since the 2000s, land outside of the Valley’s Newar cities has transformed from agricultural fields into a mixed development of planned and unplanned localities consisting of migrants from the hinterland and urbanites from the city center. -

Dr. Manmohan Singh a Fit Case for Impeachment B

Social Science in Perspective EDITORIAL BOARD Chairman & Editor-in-chief Prof. (Dr.) K. Raman Pillai Editor Dr. R.K. Suresh Kumar Executive Editor Dr. P. Sukumaran Nair Associate Editors Dr. P. Suresh Kumar Adv. K. Shaji Members Prof. Puthoor Balakrishnan Nair Prof. K. Asokan Prof.V. Sundaresan Shri. V. Dethan Shri. C.P. John Dr. Asha Krishnan Managing Editor Shri. N. Shanmughom Pillai Circulation Manager Shri. V.R. Janardhanan Published by C. ACHUTHA MENON STUDY CENTRE & LIBRARY Poojappura, Thiruvananthapuram - 695 012 Tel & Fax : 0471 - 2345850 Email : [email protected] www.achuthamenonfoundation.org ii INSTRUCTION TO AUTHORS / CONTRIBUTORS Social Science in Perspective,,, a peer reviewed journal, is the quarterly journal of C. Achutha Menon (Study Centre & Library) Foundation, Thiruvananthapuram. The journal appears in English and is published four times a year. The journal is meant to promote and assist basic and scientific studies in social sciences relevant to the problems confronting the Nation and to make available to the public the findings of such studies and research. Original, un-published research articles in English are invited for publication in the journal. Manuscripts for publication (articles, research papers, book reviews etc.) in about twenty (20) typed double-spaced pages may kindly be sent in duplicate along with a CD (MS Word). The name and address of the author should be mentioned in the title page. Tables, diagram etc. (if any) to be included in the paper should be given separately. An abstract of 50 words should also be included. References cited should be carried with in the text in parenthesis. Example (Desai 1976: 180) Bibliography, placed at the end of the text, must be complete in all respects. -

(A) S. Trrrs{ (B) St Ig{Qi 1A)Ffi

SET-A I Administrative tribunals in India are not I qnt d wrsatq qqftrq {Eii q1 rqrq-cr r'at established by : q1qrfi t' : (A) President (B) Supreme Court (A) n6qqfr ERr (B) sdqqrqEqERr (C) Chief Minister (D) All ofthese (C) E@c* ERr (D) sri-fi sqt ERr 2. Chairman of l4th Finance Commission is : 2. ffi fq-d en+rr * erqs{ * : (A) C. Rangrajan (B) Raehurajan (A) S. trRrs{ (B) st Ig{qi (C) Y. V. Reddy (D) V.K. Menon (c) sri.d tq$ (D) d. d'. trr 3. The Consumer Protection Act,, 1986 came ., sq+ftI qtqTUI sfqt{qq 1986, sil tTrrl into force on : Eiff ? (A) 1e87 (B) r9e0 (A) 1e87 (B) 19e0 (C) 1991 @) Noneof these (c) leel (D) fl+ t 6ti Tfi 4. Arsenic poisoning from drinking water leads 4 ++ + q+ q s16f65-t*v* +'nq wr *m to: B: (A) Cold @) Keratosis (A) ssT (B) +{dFss (C) Ttphoid @) None of these (q zIqsl{s (D) 3T+{a{+$:rd 5. The aim of "Skill India Mission" is to equip 5. "fisa EFsqr fts1q" q1 g-<{q f"-s s{ 500 million Indians with skills by which year- a-*'soo fqfu{H Sqlet qi g{(r< q{r+ t z (A) 2030 (B) 202s (A) 2030 (B) 202s (c) 2022 @) 2020 (c) 2022 (D) 2020 6, In which state the first Non-Government 6. r+q {q c qr{dlq Td 6,,r T6-dr rR-qrsrt Railway Project oflndian Railways has been i-d cRqhi-{ Erd d i W E1 .rfr- commissioned recently ? 1a)ffi (B) f{ffiq (A) Delhi (B) Sikkim (c) q6Rrq (D) re{rd (C) Maharashtra (D) Gujarat 7.