Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personality Profiles of Florence And

A REVIEW OF BRUCE ROBINSON'S BOOK AND THE MAYBRICK CONNECTION By Chris Jones (author of the Maybrick A to Z) If you haven't read Bruce Robinson's recent book on Jack the Ripper and the alleged connection to Michael Maybrick, then you must. It is long and detailed, though you maybe shocked by some of his language; for example, he refers to the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, as the 'boss c--t of his class.'1 Robinson makes a strong case that there was a Masonic link to the murders and that the Establishment were keen to cover up certain incidents; for example, the truncated manner in which the coroner's inquest into the death of Mary Kelly was conducted. Robinson also makes a strong case that many of the letters sent to the police may have come from the serial killer himself. As well as the canonical murders, he also examines some less well known events which he argues are linked to the Ripper killings; for example, the 'Whitehall Mystery' and the discovery of the human headless, limbless torso on the building site that was to become New Scotland Yard. Some of the most important sections of Robinson's book deal with the relationship between Michael Maybrick and his brother James, and with James's wife, Florence. Three of his core arguments are that Michael 'fingered' James to be Jack the Ripper and (with the help of others) had him murdered and finally, with the help of high-ranking Masonic figures, had Florence blamed for the crime as she had 'discovered the truth of a terrible secret.'2 Although many of Robinson's arguments are supported by research, some of the important assertions he makes concerning the Maybricks, lack evidence and are therefore open to question. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Acta Pediátrica de México ISSN: 0186-2391 ISSN: 2395-8235 [email protected] Instituto Nacional de Pediatría México Avilés-Martínez, Karla Isis; Villalobos-Lizardi, José Carlos; López-Enríquez, Adriana Venta clandestina de rodenticidas, un problema de salud pública. Reporte de dos casos Acta Pediátrica de México, vol. 40, núm. 2, 2019, pp. 71-84 Instituto Nacional de Pediatría México Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=423665708004 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto CASO CLÍNICO DE INTERÉS ESPECIAL Acta Pediatr Mex. 2019 marzo-abril;40(2):71-84. Venta clandestina de rodenticidas, un problema de salud pública. Reporte de dos casos Clandestine sale of rodenticides, a health problem. Report of two cases Karla Isis Avilés-Martínez,1 José Carlos Villalobos-Lizardi,2 Adriana López-Enríquez3 Resumen ANTECEDENTES: La venta clandestina de rodenticidas es una manifestación de la pobreza y la exclusión social. Los rodenticidas adquiridos en estas circunstancias son accesibles porque tienen un canal de distribución eficiente. Su disponibilidad en casa, sin medidas de seguridad adecuadas y estrictas, representa un problema de salud potencialmente letal debido al contenido, falsificación, adulteración y etiquetado inadecuado o ausente. CASOS CLÍNICOS: Se reportan dos casos clínicos, no letales, de niños previamente sanos que ingirieron rodenticidas no etiquetados y obtenidos de la venta ilegal ambulante. El primer caso sufrió intoxicación por difetaliona (Clase Ia), rodenticida anticoagulante de segunda generación (en la bibliografía se reporta intoxicación en dos niños). -

Martin Fido 1939–2019

May 2019 No. 164 MARTIN FIDO 1939–2019 DAVID BARRAT • MICHAEL HAWLEY • DAVID pinto STEPHEN SENISE • jan bondeson • SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST NINA & howard brown • THE BIG QUESTION victorian fiction • the latest book reviews Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 164 May 2019 EDITORIAL Adam Wood SECRETS OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH David Barrat DEAR BLUCHER: THE DIARY OF JACK THE RIPPER David Pinto TUMBLETY’S SECRET Michael Hawley THE FOURTH SIGNATURE Stephen Senise THE BIG QUESTION: Is there some undiscovered document which contains convincing evidence of the Ripper’s identity? Spotlight on Rippercast THE POLICE, THE JEWS AND JACK THE RIPPER THE PRESERVER OF THE METROPOLIS Nina and Howard Brown BRITAIN’S MOST ANCIENT MURDER HOUSE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: NO LIVING VOICE by THOMAS STREET MILLINGTON Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Poison Prevention Packaging: a Guide for Healthcare Professionals

PPooiissoonn PPrreevveennttiioonn PPaacckkaaggiinngg:: AA GGuuiiddee FFoorr HHeeaalltthhccaarree PPrrooffeessssiioonnaallss REVISED 2005 CPSC 384 US. CONSUMER PRODUCT SAFETY COMMISSION, WASHINGTON, D.C. 20207 THIS BROCHURE BROUGHT TO YOU BY: U.S. CONSUMER PRODUCT SAFETY COMMISSION Washington, DC 20207 Web site: www.cpsc.gov Toll-free hotline: 1-800-638-2772 The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) is a federal agency that helps keep families and children safe in and around their homes. For more information, call the CPSC’s toll-free hotline at 1-800-638-2772 or visit its website at http://www.cpsc.gov. Poison Prevention Packaging: A Guide For Healthcare Professionals (revised 2005) Preface The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) administers the Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970 (PPPA), 15 U.S.C. §§ 1471-1476. The PPPA requires special (child-resistant and adult-friendly) packaging of a wide range of hazardous household products including most oral prescription drugs. Healthcare professionals are more directly involved with the regulations dealing with drug products than household chemical products. Over the years that the regulations have been in effect, there have been remarkable declines in reported deaths from ingestions by children of toxic household substances including medications. Despite this reduction in deaths, many children are poisoned or have "near-misses" with medicines and household chemicals each year. Annually, there are about 30 deaths of children under 5 years of age who are unintentionally poisoned. Data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (a CPSC database of emergency room visits) indicate that in 2003, an estimated 78,000 children under 5 years of age were treated for poisonings in hospital emergency rooms in the United States. -

Strange, and Ultimately Dangerous, Credentialing Scenarios Highlight the Need for Msps’ Roles to Protect the Public

Strange, and ultimately dangerous, credentialing scenarios highlight the need for MSPs’ roles to protect the public April 3, 2018 For those of you who were unable to join us at NAMSS this year, we thought you might enjoy a recap of our session regarding strange credentialing scenarios. It is true that fact can be stranger than fiction, but these situations make it very clear that the role of the MSP is critical in today’s fast-paced world. The Danger of Not Doing Your Homework We begin with a history lesson — Michael Swango. He was valedictorian of his class and awarded a National Merit scholarship. His favorite movie was “Silence of the Lambs,” and he kept a scrapbook of car wrecks. He graduated from medical school in 1983, and during that time, five of the patients he cared for died. He obtained a surgical internship and subsequently, despite a poor evaluation, a neurosurgery residency at The Ohio State University College of Medicine (from which he was ultimately terminated for slovenly work). His nickname was “Double-O Swango.” Nursing staff expressed their concerns, but administration thought they were being “paranoid.” He was licensed as a physician in the state of Ohio in 1984. This is where it gets interesting. In 1991, he legally changed his name to Daniel Adams after having been sentenced to five years in prison for aggravated battery — he poisoned his coworkers while working as an EMT. He then forged his criminal record to reduce the charge and created a “Restoration of Civil Rights” letter allegedly from the Governor of Virginia. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

Approach to the Poisoned Patient

PED-1407 Chocolate to Crystal Methamphetamine to the Cinnamon Challenge - Emergency Approach to the Intoxicated Child BLS 08 / ALS 75 / 1.5 CEU Target Audience: All Pediatric and adolescent ingestions are common reasons for 911 dispatches and emergency department visits. With greater availability of medications and drugs, healthcare professionals need to stay sharp on current trends in medical toxicology. This lecture examines mind altering substances, initial prehospital approach to toxicology and stabilization for transport, poison control center resources, and ultimate emergency department and intensive care management. Pediatric Toxicology Dr. James Burhop Pediatric Emergency Medicine Children’s Hospital of the Kings Daughters Objectives • Epidemiology • History of Poisoning • Review initial assessment of the child with a possible ingestion • General management principles for toxic exposures • Case Based (12 common pediatric cases) • Emerging drugs of abuse • Cathinones, Synthetics, Salvia, Maxy/MCAT, 25I, Kratom Epidemiology • 55 Poison Centers serving 295 million people • 2.3 million exposures in 2011 – 39% are children younger than 3 years – 52% in children younger than 6 years • 1-800-222-1222 2011 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System Introduction • 95% decline in the number of pediatric poisoning deaths since 1960 – child resistant packaging – heightened parental awareness – more sophisticated interventions – poison control centers Epidemiology • Unintentional (1-2 -

Davince Tools Generated PDF File

oRAGNET ·THE DAILY ··NEWS MOZART 1,.\NUARY • 21, 22, available al 23. 24, 25, 26 ~~· Vol. 64. No. 18 ST. JOHN'S, NEWFOUNDLAND, TUESDAY, JANUARY 22/1957 (Price .5 cents) Charles Hutton & Sons. - ~----------------·--~--------·----------~---------------------------------·----------------------------~----~~~~~---------- Of larva .. Debate On ·oristructio·n roup irited .' .. • eechl From Throne' oustn , , ;· - r::crtion-hrr·llhc Conscrvatil"es around theil· : assistance for rcdcl"eloping !bCU" 0 osts 1 1 I ' .. ·.' . · , .'·Jf,rll m the motion's claim that tb~ govcJ\i·! won1out areas. · i• ·• · ... I ment has lost the confidcuc~ I REDEVELOP SLUliiS ' -----------~--..._,.;---------.....:....----------- ··:·. ;,, ·:\- ;, c bunched a of Parliament and the conntr1· 'I The National Housing Act pro- .::";,· . f •nnrt· CC'Frr, through its "incliffercncc, inerli:t, ·vidcd that the federal SOI'~rn- - ·. ,. ,, Hn11 tiryin;: i and lack of leadership." 1 ment, through its Central :llort- Help' Lower . · .... , ·' :1 he tr:·in~ i The ''cxtr:wr1iinary" t h i •i r: · gng~ and Housing Corporation, . _ '· , · p.,rty mal·~·· , about this "is that in fact tb~ I would share costs of sturlying • :1 ..~ 1 .. , . :. 111 !he next i only group lu this House to whicll 1 municipal areas for redevelop. _- , .·., , · ,:,llHiay .•Tun~ tho<c words Ci\n be properly as· , mcnt. It also would split costs · . .• ,, dwt:.~nt:r'i I crihcd is the official OJ1position: ol acquiring R\111 clearing such Income Groups .. ' 1: • , · 1;.miin~r 10 , Thi~ had been particularly nJl· 1areas, either on a fcdcrnl-prov- • 1!w ~o1·crn· ' parent when Opposition Leaer . ineial-munlcipnl basis or, with TORONTO (CP) - The Canadian Construction .1;:riculture ! Dtrfcnh:~k·~r. in re;:nril to the rcc· 1 prol'incial approval, directly with r.i\ CPR firemen's strike, said I the munlcipa!lly. -

Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non-Target Organisms Katherine Horak U.S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Publications Health Inspection Service 2018 Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non-target Organisms Katherine Horak U.S. Department of Agriculture, [email protected] Penny M. Fisher Landcare Research Brian M. Hopkins Landcare Research Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Part of the Life Sciences Commons Horak, Katherine; Fisher, Penny M.; and Hopkins, Brian M., "Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non- target Organisms" (2018). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 2091. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/2091 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Chapter 4 Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non-target Organisms Katherine E. Horak, Penny M. Fisher, and Brian Hopkins 1 Introduction The concentration of a compound at the site of action is a determinant of its toxicity. This principle is affected by a variety of factors including the chemical properties of the compound (pKa, lipophilicity, molecular size), receptor binding affinity, route of exposure, and physiological properties of the organism. Many compounds have to undergo chemical changes, biotransformation, into more toxic or less toxic forms. Because of all of these variables, predicting toxic effects and performing risk assess- ments of compounds based solely on dose are less accurate than those that include data on absorption, distribution, metabolism (biotransformation), and excretion of the compound. -

Serial Killers

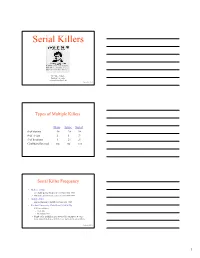

Serial Killers Dr. Mike Aamodt Radford University [email protected] Updated 01/24/2010 Types of Multiple Killers Mass Spree Serial # of victims 4+ 2+ 3+ # of events 1 1 3+ # of locations 1 2+ 3+ Cooling-off period no no yes Serial Killer Frequency • Hickey (2002) – 337 males and 62 females in U.S. from 1800-1995 – 158 males and 29 females in U.S. from 1975-1995 • Gorby (2000) – 300 international serial killers from 1800-1995 • Radford University Data Base (1/24/2010) – 1,961 serial killers • US: 1,140 • International: 821 – Number of serial killers goes down with each update because many names listed as serial killers are not actually serial killers Updated 01/24/2010 1 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics - Worldwide • Male – Our data base: 88.27% – Kraemer, Lord & Heilbrun (2004) study of 157 serial killers: 96% • White – 66.5% of all serial killers (68% in Kraemer et al, 2004) – 64.3% of male serial killers – 83% of female serial killers • Average intelligence – Mean of 101 in our data base (median = 100) –n = 107 • Seldom involved with groups Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Age at First Kill Race N Mean Our data (2010) 1,518 29.0 Kraemer et al. (2004) 157 31 Hickey (2002) 28.5 Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics – Average age is 29.0 • Males – 28.8 is average age at first kill • 9 is the youngest (Robert Dale Segee) • 72 is the oldest (Ray Copeland) – Jesse Pomeroy (Boston in the 1870s) • Killed 2 people and tortured 8 by the age of 14 • Spent 58 years in solitary confinement until he died • Females – 30.3 is average age at first kill • 11 is youngest (Mary Flora Bell) • 66 is oldest (Faye Copeland) Updated 01/24/2010 2 General Serial Killer Profile Race Race U.S. -

The Persecution of Doctor Bodkin Adams

THE PHYSICIAN FALSELY ACCUSED: The Persecution Of Doctor Bodkin Adams When the Harold Shipman case broke in 1998, press coverage although fairly extensive was distinctly muted. Shipman was charged with the murder of Mrs Kathleen Grundy on September 7, and with three more murders the following month, but even then and with further exhumations in the pipeline, the often scurrilous tabloids kept up the veneer of respectability, and there was none of the lurid and sensationalist reporting that was to accompany the Soham inquiry four years later. It could be that the apparent abduction and subsequent gruesome discovery of the remains of two ten year old girls has more ghoul appeal than that of a nondescript GP who had taken to poisoning mostly elderly women, or it could be that some tabloid hacks have long memories and were reluctant to jump the gun just in case Shipman turned out to be another much maligned, benevolent small town doctor, for in 1956, a GP in the seaside town of Eastbourne was suspected and at times accused of being an even more prolific serial killer than Harold Shipman. Dr Bodkin Adams would eventually stand trial for the murder of just one of his female patients; and was cleared by a jury in less than three quarters of an hour. How did this come about? As the distinguished pathologist Keith Simpson pointed out, the investigation into Dr Adams started as idle gossip, “a mere whisper on the seafront deck chairs of Eastbourne” which first saw publication in the French magazine Paris Match - outside the jurisdiction of Britain’s libel laws.