Personality Profiles of Florence And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Fido 1939–2019

May 2019 No. 164 MARTIN FIDO 1939–2019 DAVID BARRAT • MICHAEL HAWLEY • DAVID pinto STEPHEN SENISE • jan bondeson • SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST NINA & howard brown • THE BIG QUESTION victorian fiction • the latest book reviews Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 164 May 2019 EDITORIAL Adam Wood SECRETS OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH David Barrat DEAR BLUCHER: THE DIARY OF JACK THE RIPPER David Pinto TUMBLETY’S SECRET Michael Hawley THE FOURTH SIGNATURE Stephen Senise THE BIG QUESTION: Is there some undiscovered document which contains convincing evidence of the Ripper’s identity? Spotlight on Rippercast THE POLICE, THE JEWS AND JACK THE RIPPER THE PRESERVER OF THE METROPOLIS Nina and Howard Brown BRITAIN’S MOST ANCIENT MURDER HOUSE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: NO LIVING VOICE by THOMAS STREET MILLINGTON Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. -

Timothy Ferris Or James Oberg on 1 David Thomas on Eries

The Bible Code II • The James Ossuary Controversy • Jack the Ripper: Case Closed? The Importance of Missing Information Acupuncture, Magic, i and Make-Believe Walt Whitman: When Science and Mysticism Collide Timothy Ferris or eries 'Taken' James Oberg on 1 fight' Myth David Thomas on oking Gun' Published by the Comm >f Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION off Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAl (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts and Loren Pankratz, psychologist Oregon Health Toronto Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University of Miami Sciences Univ. Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Oregon Al Hibbs. scientist Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist, MIT Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, execu England Journal of Medicine understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky Indiana Univ Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Chicago consumer advocate. Allentown, Pa. and professor of history of science. Harvard Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor of Barry Beyerstein.* biopsychologist. -

THE FIRST PURPOSE BUILT MOSQUE in BRITAIN (BEAT THAT LONDON & CARDIFF & LIVERPOOL) Iain Wakeford 2015

THE FIRST PURPOSE BUILT MOSQUE IN BRITAIN (BEAT THAT LONDON & CARDIFF & LIVERPOOL) Iain Wakeford 2015 ometimes Local History can be just that – purely local, the opening of a new school, the building of a chapel or church – but other times it can have a national or even international angle. This week, as we reach the year 1889, there are at least three S pieces of local history that meet that criteria, making Woking known the world over in Victorian Times (even if it is forgotten in some places now)! The former Royal Dramatic College bought by Dr Leitner for his Oriental Institute. ou may recall from earlier articles that in Dr Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner, founder of the Oriental enhanced in status to become the University of 1877 the Royal Dramatic College at Institute in Woking - Surrey’s First University. the Punjab! He founded schools, libraries, Y Maybury closed and the buildings were literary associations and journals in India, but in sold to a property developer called Alfred the late 1870’s decided to return to Europe to Chabot. With plenty of undeveloped land still for carry out research at Heidelberg University and sale nearby he soon found that the buildings to do work for the Prussian, Austrian and British were something of a ‘white elephant’, with his Governments. It was probably about this time only solution to try to find another institution to that he thought about setting up an ‘Oriental take over the site. In 1884 he struck lucky Institute’ – somewhere for Europeans to study when the Hungarian born, Dr Gottlieb Wilhelm oriental language and culture before they Leitner purchased the site for his new ‘Oriental travelled to the east, and somewhere where Institute’. -

The Lost Chord, the Holy City and Williamsport, Pennsylvania

THE LOST CHORD, THE HOLY CITY AND WILLIAMSPORT, PENNSYLVANIA by Solomon Goodman, 1994 Editor's Introduction: Our late nineteenth century forbears were forever integrating the sacred and the secular. Studies of that era that attempt to focus on one or the other are doomed to miss the behind-the-scenes connections that provide the heart and soul informing the recorded events. While ostensibly unfolding the story of several connected pieces of sacred and popular music, this paper captures some of the romance and religion, the intellect and intrigue, the history and histrionics of those upon whose heritage we now build. The material presented comes from one of several ongoing research projects of the author, whose main interest is in music copyrighting. While a few United Methodist and Central Pennsylvania references have been inserted into the text at appropriate places, the style and focus are those of the author. We thank Mr. Goodman for allowing THE CHRONICLE to reproduce the fruits of his labor in this form. THE LOST CHORD One of the most popular composers of his day, Sir Arthur Sullivan is a strong candidate for the most talented and versatile secular/sacred, light/serious composer ever. This accomplished organist and author of stately hymns (including "Onward, Christian Soldiers"), is also the light-hearted composer of Gilbert and Sullivan operetta fame. During and immediately following his lifetime, however, his most successful song was the semi-sacred "The Lost Chord." In 1876 Sullivan's brother Fred, to whom he was deeply attached, fell ill and lingered for three weeks before dying. -

Home Office Spin? We Remember DON SOUDEN with Two of His Greatest Articles

August/September 2017 No. 157 Home Office Spin? We remember DON SOUDEN with two of his greatest articles THE DEVIL IN SIR ARTHUR, OBITUARY: A DOMINO SCOTLAND YARD, RICHARD GORDON Simon Stern SHERLOCK HOLMES AND A SERIAL KILLER: THE BLACKHEATH JACK IN FOUR COLORS A VERY TANGLED MYSTERY and THE Dave M Gray SKEIN TOOTING HORROR Daniel L. Friedman and Jan Bondeson MAYWEATHER VS Eugene B. Friedman McGREGOR VICTORIAN STYLE DRAGNET! PT 1 VICTORIAN FICTION Brian Young Nina and Howard BrownRipperologistWilliam 118 January Hope 2011 Hodgson1 Ripperologist 157 August/September 2017 EDITORIAL: FAREWELL, SUPE Adam Wood PARDON ME: SPIN CONTROL AT THE HOME OFFICE? Don Souden WHAT’S WRONG WITH BEING UNMOTIVATED? Don Souden THE DEVIL IN A DOMINO Simon Stern SIR ARTHUR, SCOTLAND YARD, SHERLOCK HOLMES AND A SERIAL KILLER: A VERY TANGLED SKEIN Daniel L. Friedman and Eugene B. Friedman JACK IN FOUR COLORS Dave M Gray MAYWEATHER VS McGREGOR VICTORIAN STYLE Brian Young OBITUARY: RICHARD GORDON THE BLACKHEATH MYSTERY and THE TOOTING HORROR Jan Bondeson DRAGNET! PT 1 Nina and Howard Brown VICTORIAN FICTION: THE VOICE IN THE NIGHT By William Hope Hodgson BOOK REVIEWS Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.mangobooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. -

Pltutmsj 8. >. Ptent

vto'rwfOA.'v CORRECT J J i K E I 'A i p ' G OIN G Ja w k t STYLES TO G IV E Calling Cards Party or Tea ? Our presses are turn Pretty Cards for out some pretty Tbat Purpose work these days. Printed or Blank. O U R P RIC E 25 cards for 25 cents W E K B EP By mail or at the of- All Kinds Invitation flcfe. and Regret Cards. VOL. DEI/T A, OHIO, FRIDAY MORNING, JUNE 23, 1899. ' H A RRIED . The Band boys received their new ficers who have served the association A t the home of the bride’s parents, suits Wednesday morning just in time durir g the past year so faithfully and to wear them to tbe K. P. pic-nic at Mr. and Mrs. Hugh Lilly, south of so efficiently.'^ HIM ill IS IMltl. town, on Tuesday June 20, 1899 by Swanton. Tbey are a flne set of uni forms, blue trimmed in white. They That we appreciate the earnest ef Rev. Geo. McKay, W. F. Brainard. of John Johnson’s Swanton, and Mrs. Racbel Showers. were made at Columbus, but the boys forts of the various S. S. workers in S. T. Shaffer was in Toledo Monday. A son born to Mr. and Mrs. A. A. were measured by Mr. Hirschberg of by Light Fingered Gentry. After tbe wedding ceremony and re Meister, Pettisville. the several townships, which coupled o a l M it Clark and wife were in Detroit Delta and a finer fitting lot of suits Fulton County S. -

The Lives and Times of Florence Maybrick, 1891-2015

“As the times want him to decide”: the lives and times of Florence Maybrick, 1891-2015 by Noah Miller Bachelor of Arts (Honours), University of Calgary, 2011 Graduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, University of Victoria, 2015 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History Noah Miller, 2018 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisory Committee “As the times want him to decide”: the lives and times of Florence Maybrick, 1891-2015 by Noah Miller Bachelor of Arts (Honours), University of Calgary, 2011 Graduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, University of Victoria, 2015 Supervisory Committee Dr. Simon Devereaux (Department of History) Supervisor Dr. Tom Saunders (Department of History) Departmental Member ii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Simon Devereaux (Department of History) Supervisor Dr. Tom Saunders (Department of History) Departmental Member This thesis examines major publications produced between 1891-2015 that portray the trial of Florence Maybrick. Inspired by Paul Davis’ Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge, it considers the various iterations of Florence’s story as “protean fantasies,” in which the narrative changed to reflect the realities of the time in which it was (re)written. It tracks shifting patterns of emphasis and authors’ rigid conformity to associated sets of discursive strategies to argue that this body of literature can be divided into three distinct epochs. The 1891-1912 era was characterized by authors’ instrumentalization of sympathy on Florence’s behalf in response to contemporary concerns about the administration of criminal justice in England. -

THE INDIANAPOLIS JOURNAL, TRIDAY, JULY 21, 1899. Ir,Tthenera

THE INDIANAPOLIS JOURNAL, TRIDAY, JULY 21, 1899. increasing his reputation by sulted different times, gave him a pre- Hughes. Toronto. Ont. Patriotic con- tor Library, three had been discontinued, or who "Is active OF MRS. MAYBR1CK at MANSFIELD'S DGG I. D- - suspended publication. Catholic HERO OF THE CIVIL WAR operations." He had won his command at STORY scription In which arsenic had no part. J0SIE Itcv. W. T. 1'arr. had The co-opera- ted cert- lvotlons. I.. lievlew has been suspended, the Quarterly Franklin, where the navy with MRS. MAYBRICK'S PURCHASE. Fort Wayne, Intl. army in an attack, and on Oct. 22. while 8:i p. m. "Last Days of the Confederacy." Message and Mission News have been dis- the In the afternoon of May 21 Mrs. May- Besides Christian Educa- off Beaufort, with the Ellis, he ran to New Gen. John B. Gordon. Tomlinson Hall. continued. these. Topsail inlet, boldly brick called at the drug store kept by 7;.T0 p. m. English's Opera House Presi- tion, published in Chicago, and Golden Rule, entered the inlet at THE AMERICAN WOMAK SOW IX AX 1VOMAX WHO CAUSED THE DEATH publication. LIE IT. Cl'SIIISG'S EXPLOITS IX full speed, caught the schooner Adelaide, Thomas Nokes, in the Algburth road. Liv- dent, L'nlon B. Hunt, secretary of state. of Boston, have ceased x Washington. Ky. South religious papers retain their BLOCKADE RUXMXG DAYS. with GoO barrels of turpentine and thirty-si- ENGLISH JAIL FOR Ml'RDEH. FISKi: A HELPLESS PA II A LYTIC Rev. N. W. -

Desert Island Times 16

D E S E R T I S L A N D T I M E S S h a r i n g f e l l o w s h i p i n NEWPORT SE WALES U3A No.16 3rd July 2020 The Old Green from Kingsway, c1968 A miscellany of Contributions from OUR members 1 50 Mile Challenge - Penarth - Mike Brown We like to visit Penarth several times a year. With its elegant buildings and wide tree-lined streets, Penarth retains much of its original Victorian and Edwardian character. Sometimes we get there early to watch the Balmoral embarking on a cruise. visit - http://www.waverleyexcursions.co.uk We drive through the town centre and then left at the Town Clock Roundabout and park in a side street. We walk back to the roundabout (WCs in the vicinity) then first left down Windsor Terrace towards the sea, crossing the road into Alexandra Park. There are panoramic views of the Bristol Channel as we make our way down towards the sea front past colourful ornamental gardens, leafy glades, a fishpond, aviary and the bandstand. ***Crossing Bridgeman Road we enter Windsor Gardens with more floral displays and sea views. Bordering the park are magnificent large town houses of local blue lias stone, once the homes of sea captains, coal magnates and businessmen: some have been converted to retirement homes. We exit onto Cliff Hill and cross the road onto Telegraph Way. This is a mile-long cliff-top path that leads to Lavernock Point. There is a plaque on the church wall to commemorate Marconi's first transmitted radio signal across open sea to the island of Flatholm, from here, on 13th May 1897. -

Verdict in Dispute, by Edgar Marcus Lustgarten

VERDICT IN DISPUTE 1 By the same author: A CASE TO ANSWER BLONDIE 1SCARIOT VERDICT in DISPUTE EDGAR LUSTGARTEN 526633 ALLAN WINGATE LONDON AND NEW YORK First published mcmxlix by Allan Wingate (Publishers) Limited 12 Beauchamp Place London S W 3 122 East th Street New Set in Linotype Granjon and printed in Great Britain by Billing and Sons Ltd Guildford and Esher PREFACE Six famous murder trials are examined in this book. All six verdicts are open to dispute. Three, in my belief, are demon- strably bad. I have tried not only to analyse the facts but to recreate the atmosphere in which these trials were fought, so that the reader can determine the dominating influences that led to result their unsatisfactory shortcomings of counsel, inepti- tude of judge, prejudice of jury, or any other weakness to which the human race is constitutionally prone. There is reason to suppose that, in British and American courts, miscarriages of justice are relatively rare. But how- ever infrequent, they still affront the conscience, and study of will not if those that disfigure the past be profitless the know- of ledge thereby gained lessens the chance repetition. For ANNE SINNETT CONTENTS FLORENCE MAYBRICK Page 9 STEINIEMORRISON 43 NORMANTHORNE 88 EDITH THOMPSON 127 WILLIAM HERBERT WALLACE 163 LIZZIE BORDEN 2O6 APPENDIX 251 FLORENCE MAYBRICK PLANNED, deliberate killing is no drawing-room accomplish- ment. It needs callousness of heart, insensitivity of mind, in- difference to suffering and contempt for human life. These are grim qualities; repulsive in a man, in a woman against nature. The calculating murderer is vile but comprehensible; the calculating murderess is an enigmatic paradox. -

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE Steven B. Karch, MD, SERIES EDITOR CRIMINAL POISONING: INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS, SECOND EDITION, by John H. Trestrail, III, 2007 MARIJUANA AND THE CANNABINOIDS, edited by Mahmoud A. ElSohly, 2007 FORENSIC PATHOLOGY OF TRAUMA: COMMON PROBLEMS FOR THE PATHOLOGIST, edited by Michael J. Shkrum and David A. Ramsay, 2007 THE FORENSIC LABORATORY HANDBOOK: PROCEDURES AND PRACTICE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Carla Noziglia, 2006 SUDDEN DEATHS IN CUSTODY, edited by Darrell L. Ross and Ted Chan, 2006 DRUGS OF ABUSE: BODY FLUID TESTING, edited by Raphael C. Wong and Harley Y. Tse, 2005 A PHYSICIAN’S GUIDE TO CLINICAL FORENSIC MEDICINE: SECOND EDITION, edited by Margaret M. Stark, 2005 FORENSIC MEDICINE OF THE LOWER EXTREMITY: HUMAN IDENTIFICATION AND TRAUMA ANALYSIS OF THE THIGH, LEG, AND FOOT, by Jeremy Rich, Dorothy E. Dean, and Robert H. Powers, 2005 FORENSIC AND CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF SOLID PHASE EXTRACTION, by Michael J. Telepchak, Thomas F. August, and Glynn Chaney, 2004 HANDBOOK OF DRUG INTERACTIONS: A CLINICAL AND FORENSIC GUIDE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Lionel P. Raymon, 2004 DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS: TOXICOLOGY AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Melanie Johns Cupp and Timothy S. Tracy, 2003 BUPRENOPHINE THERAPY OF OPIATE ADDICTION, edited by Pascal Kintz and Pierre Marquet, 2002 BENZODIAZEPINES AND GHB: DETECTION AND PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Salvatore J. Salamone, 2002 ON-SITE DRUG TESTING, edited by Amanda J. Jenkins and Bruce A. Goldberger, 2001 BRAIN IMAGING IN SUBSTANCE ABUSE: RESEARCH, CLINICAL, AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS, edited by Marc J. Kaufman, 2001 CRIMINAL POISONING INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS Second Edition John Harris Trestrail, III, RPh, FAACT, DABAT Center for the Study of Criminal Poisoning, Grand Rapids, MI © 2007 Humana Press Inc. -

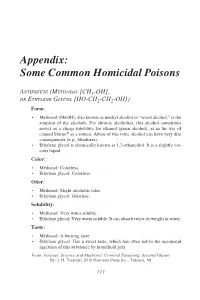

Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons

Appendix 111 Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons ANTIFREEZE (METHANOL [CH3-OH], OR ETHYLENE GLYCOL [HO-CH2-CH2-OH]) Form: • Methanol (MeOH), also known as methyl alcohol or “wood alcohol,” is the simplest of the alcohols. For chronic alcoholics, this alcohol sometimes serves as a cheap substitute for ethanol (grain alcohol), as in the use of canned Sterno® as a source. Abuse of this toxic alcohol can have very dire consequences (e.g., blindness). • Ethylene glycol is chemically known as 1,2-ethanediol. It is a slightly vis- cous liquid. Color: • Methanol: Colorless. • Ethylene glycol: Colorless. Odor: • Methanol: Slight alcoholic odor. • Ethylene glycol: Odorless. Solubility: • Methanol: Very water soluble. • Ethylene glycol: Very water soluble. It can absorb twice its weight in water. Taste: • Methanol: A burning taste. • Ethylene glycol: Has a sweet taste, which has often led to the accidental ingestion of this substance by household pets. From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ 111 112 Common Homicidal Poisons Source: • Methanol: Is a common ingredient in windshield-washing solutions, dupli- cating fluids, and paint removers and is commonly found in gas-line anti- freeze, which may be 95% (v/v) methanol. • Ethylene glycol: Is commonly found in radiator antifreeze (in a concentration of ~95% [v/v]), and antifreeze products used in heating and cooling systems. Lethal Dose: • Methanol: The fatal dose is estimated to be 30–240 mL (20–150 g). • Ethylene glycol: The approximate fatal dose of 95% ethylene glycol is esti- mated to be 1.5 mL/kg.