Verdict in Dispute, by Edgar Marcus Lustgarten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personality Profiles of Florence And

A REVIEW OF BRUCE ROBINSON'S BOOK AND THE MAYBRICK CONNECTION By Chris Jones (author of the Maybrick A to Z) If you haven't read Bruce Robinson's recent book on Jack the Ripper and the alleged connection to Michael Maybrick, then you must. It is long and detailed, though you maybe shocked by some of his language; for example, he refers to the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, as the 'boss c--t of his class.'1 Robinson makes a strong case that there was a Masonic link to the murders and that the Establishment were keen to cover up certain incidents; for example, the truncated manner in which the coroner's inquest into the death of Mary Kelly was conducted. Robinson also makes a strong case that many of the letters sent to the police may have come from the serial killer himself. As well as the canonical murders, he also examines some less well known events which he argues are linked to the Ripper killings; for example, the 'Whitehall Mystery' and the discovery of the human headless, limbless torso on the building site that was to become New Scotland Yard. Some of the most important sections of Robinson's book deal with the relationship between Michael Maybrick and his brother James, and with James's wife, Florence. Three of his core arguments are that Michael 'fingered' James to be Jack the Ripper and (with the help of others) had him murdered and finally, with the help of high-ranking Masonic figures, had Florence blamed for the crime as she had 'discovered the truth of a terrible secret.'2 Although many of Robinson's arguments are supported by research, some of the important assertions he makes concerning the Maybricks, lack evidence and are therefore open to question. -

Martin Fido 1939–2019

May 2019 No. 164 MARTIN FIDO 1939–2019 DAVID BARRAT • MICHAEL HAWLEY • DAVID pinto STEPHEN SENISE • jan bondeson • SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST NINA & howard brown • THE BIG QUESTION victorian fiction • the latest book reviews Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 164 May 2019 EDITORIAL Adam Wood SECRETS OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH David Barrat DEAR BLUCHER: THE DIARY OF JACK THE RIPPER David Pinto TUMBLETY’S SECRET Michael Hawley THE FOURTH SIGNATURE Stephen Senise THE BIG QUESTION: Is there some undiscovered document which contains convincing evidence of the Ripper’s identity? Spotlight on Rippercast THE POLICE, THE JEWS AND JACK THE RIPPER THE PRESERVER OF THE METROPOLIS Nina and Howard Brown BRITAIN’S MOST ANCIENT MURDER HOUSE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: NO LIVING VOICE by THOMAS STREET MILLINGTON Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. -

A Veritable Revolution: the Court of Criminal Appeal in English

A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS B.A. University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1986 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 Cecile Arden Phillips, Candidate for the Masters of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In a historic speech to the House of Commons on April 17, 1907, British Attorney General, John Lawson Walton, proposed the formation of what was to be the first court of criminal appeal in English history. Such a court had been debated, but ultimately rejected, by successive governments for over half a century. In each debate, members of the judiciary declared that a court for appeals in criminal cases held the potential of destroying the world-respected English judicial system. The 1907 debates were no less contentious, but the newly elected Liberal government saw social reform, including judicial reform, as their highest priority. After much compromise and some of the most overwrought speeches in the history of Parliament, the Court of Criminal Appeal was created in August 1907 and began hearing cases in May 1908. A Veritable Revolution is a social history of the Court’s first fifty years. There is no doubt, that John Walton and the other founders of the Court of Criminal Appeal intended it to provide protection from the miscarriage of justice for English citizens convicted of criminal offenses. -

The Stabbing of George Harry Storrs

THE STABBING OF GEORGE HARRY STORRS JONATHAN GOODMAN $15.00 THE STABBING OF GEORGE HARRY STORRS BY JONATHAN GOODMAN OCTOBER OF 1910 WAS A VINTAGE MONTH FOR murder trials in England. On Saturday, the twenty-second, after a five-day trial at the Old Bailey in London, the expatriate American doctor Hawley Harvey Crippen was found guilty of poi soning his wife Cora, who was best known by her stage name of Belle Elmore. And on the following Monday, Mark Wilde entered the dock in Court Number One at Chester Castle to stand trial for the stabbing of George Harry Storrs. He was the second person to be tried for the murder—the first, Cornelius Howard, a cousin of the victim, having earlier been found not guilty. The "Gorse Hall mystery," as it became known from its mise-en-scene, the stately residence of the murdered man near the town of Stalybridge in Cheshire, was at that time almost twelve months old; and it had captured the imagination of the British public since the morning of November 2, 1909, when, according to one reporter, "the whole country was thrilled with the news of the outrage." Though Storrs, a wealthy mill-owner, had only a few weeks before erected a massive alarm bell on the roof of Gorse Hall after telling the police of an attempt on his life, it did not save him from being stabbed to death by a mysterious intruder. Storrs died of multiple wounds with out revealing anything about his attacker, though it was the impression of [Continued on back flap] THE STABBING OF GEORGE HARRY STORRS THE STABBING OF JONATHAN GOODMAN OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS COLUMBUS Copyright © 1983 by the Ohio State University Press All rights reserved. -

Intouch Liverpool

WINTER 2018 InTouch Liverpool www.cii.co.uk/liverpool I @insureLiv I The Insurance Institute of Liverpool WELCOME Well doesn’t time fly when you’re having fun! I’m now half way through my year as President of the Insurance Institute of Liverpool and our committee have been extremely busy over the past six months organising and hosting events for all our members. We are very lucky to have such a dedicated This is always a fun event to get us all in group of people on our committee. So the festive mood. If you haven’t booked much energy goes into providing support your place yet, please register through our for our members at a local level and a lot of website. it is done in the committee’s own time. January will see our annual dinner take The Insurance Institute Games got off to a place at the Crown Plaza in Liverpool. brilliant start with nine teams participating. Bookings are already being taken for this After the first two events Barnett prestigious event and we hope to see many Waddingham are at the top of our leader of you there in your Black-Tie regalia. board, with Quilter Cheviot and Pavis close behind. Lots of fun was had at our To mark International Women’s Day next school sports day-style event. Participants March, we’re hosting a special social event got to enjoy lots of types of sports, it was jointly with the CISI in Liverpool with an extremely competitive, and we’re pleased emphasis on diversity and equality. -

The Lost Chord, the Holy City and Williamsport, Pennsylvania

THE LOST CHORD, THE HOLY CITY AND WILLIAMSPORT, PENNSYLVANIA by Solomon Goodman, 1994 Editor's Introduction: Our late nineteenth century forbears were forever integrating the sacred and the secular. Studies of that era that attempt to focus on one or the other are doomed to miss the behind-the-scenes connections that provide the heart and soul informing the recorded events. While ostensibly unfolding the story of several connected pieces of sacred and popular music, this paper captures some of the romance and religion, the intellect and intrigue, the history and histrionics of those upon whose heritage we now build. The material presented comes from one of several ongoing research projects of the author, whose main interest is in music copyrighting. While a few United Methodist and Central Pennsylvania references have been inserted into the text at appropriate places, the style and focus are those of the author. We thank Mr. Goodman for allowing THE CHRONICLE to reproduce the fruits of his labor in this form. THE LOST CHORD One of the most popular composers of his day, Sir Arthur Sullivan is a strong candidate for the most talented and versatile secular/sacred, light/serious composer ever. This accomplished organist and author of stately hymns (including "Onward, Christian Soldiers"), is also the light-hearted composer of Gilbert and Sullivan operetta fame. During and immediately following his lifetime, however, his most successful song was the semi-sacred "The Lost Chord." In 1876 Sullivan's brother Fred, to whom he was deeply attached, fell ill and lingered for three weeks before dying. -

Victorian Jury Court Advocacy and Signs of Fundamental Change

Victorian jury court advocacy and signs of fundamental change WATSON, Andrew <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9500-2249> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/14305/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version WATSON, Andrew (2016). Victorian jury court advocacy and signs of fundamental change. Journal on European History of Law, 7 (1), 36-44. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Victorian jury court advocacy and signs of fundamental change. Abstract. Over the last three centuries advocacy in the courts of England and Wales, and other common law countries, has been far from static. In the second half of the 19th century, roughly until the beginning years of the 1880’s, the foremost style of advocacy before juries in English criminal and civil cases was melodramatic, declamatory and lachrymose Aggressive and intimidating cross-examination of witnesses took place, sometimes, unless restrained by judges, descending into bullying. Questions asked often had more to do with a blunderbuss than with a precise forensic weapon. Closing speeches were frequently long and repetitious. Appeals to emotion, and prejudice, usually reaching their peak in the peroration, were often greater than those to reason. The Diety and the Bible were regularly invoked. Vivid and floral language was employed and poetry liberally put to use to awaken generous sympathies. Examples of this style of advocacy, parodied amongst others by Gilbert and Sullivan's in their Trial by jury - a short comic operetta, first staged in 1875, about a trial of an action in the Court of Exchequer for breach of promise to marry, are presented. -

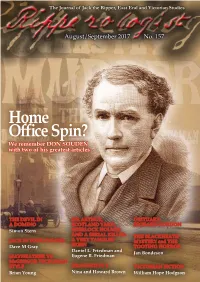

Home Office Spin? We Remember DON SOUDEN with Two of His Greatest Articles

August/September 2017 No. 157 Home Office Spin? We remember DON SOUDEN with two of his greatest articles THE DEVIL IN SIR ARTHUR, OBITUARY: A DOMINO SCOTLAND YARD, RICHARD GORDON Simon Stern SHERLOCK HOLMES AND A SERIAL KILLER: THE BLACKHEATH JACK IN FOUR COLORS A VERY TANGLED MYSTERY and THE Dave M Gray SKEIN TOOTING HORROR Daniel L. Friedman and Jan Bondeson MAYWEATHER VS Eugene B. Friedman McGREGOR VICTORIAN STYLE DRAGNET! PT 1 VICTORIAN FICTION Brian Young Nina and Howard BrownRipperologistWilliam 118 January Hope 2011 Hodgson1 Ripperologist 157 August/September 2017 EDITORIAL: FAREWELL, SUPE Adam Wood PARDON ME: SPIN CONTROL AT THE HOME OFFICE? Don Souden WHAT’S WRONG WITH BEING UNMOTIVATED? Don Souden THE DEVIL IN A DOMINO Simon Stern SIR ARTHUR, SCOTLAND YARD, SHERLOCK HOLMES AND A SERIAL KILLER: A VERY TANGLED SKEIN Daniel L. Friedman and Eugene B. Friedman JACK IN FOUR COLORS Dave M Gray MAYWEATHER VS McGREGOR VICTORIAN STYLE Brian Young OBITUARY: RICHARD GORDON THE BLACKHEATH MYSTERY and THE TOOTING HORROR Jan Bondeson DRAGNET! PT 1 Nina and Howard Brown VICTORIAN FICTION: THE VOICE IN THE NIGHT By William Hope Hodgson BOOK REVIEWS Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.mangobooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. -

The Lives and Times of Florence Maybrick, 1891-2015

“As the times want him to decide”: the lives and times of Florence Maybrick, 1891-2015 by Noah Miller Bachelor of Arts (Honours), University of Calgary, 2011 Graduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, University of Victoria, 2015 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History Noah Miller, 2018 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisory Committee “As the times want him to decide”: the lives and times of Florence Maybrick, 1891-2015 by Noah Miller Bachelor of Arts (Honours), University of Calgary, 2011 Graduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, University of Victoria, 2015 Supervisory Committee Dr. Simon Devereaux (Department of History) Supervisor Dr. Tom Saunders (Department of History) Departmental Member ii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Simon Devereaux (Department of History) Supervisor Dr. Tom Saunders (Department of History) Departmental Member This thesis examines major publications produced between 1891-2015 that portray the trial of Florence Maybrick. Inspired by Paul Davis’ Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge, it considers the various iterations of Florence’s story as “protean fantasies,” in which the narrative changed to reflect the realities of the time in which it was (re)written. It tracks shifting patterns of emphasis and authors’ rigid conformity to associated sets of discursive strategies to argue that this body of literature can be divided into three distinct epochs. The 1891-1912 era was characterized by authors’ instrumentalization of sympathy on Florence’s behalf in response to contemporary concerns about the administration of criminal justice in England. -

“I Will Take Your Answer One Way Or Another” the Oscar Wilde Trial Transcripts As Literary Artefacts

Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Anglistisches Seminar Prof. Dr. Peter Paul Schnierer Magisterarbeit “I Will Take Your Answer One Way or Another” The Oscar Wilde Trial Transcripts as Literary Artefacts Benjamin Merkler Boxbergring 12 69126 Heidelberg 06221-7350416 0179-4788849 [email protected] Magisterstudium: Anglistik Nebenfächer: Philosophie, Öffentliches Recht Abgabetermin: 02. Januar 2010 Content 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Problems of Transcription 5 1.2 New Historicism and Paratexts 8 2 The Background of the Oscar Wilde Trials 10 2.1 The Legal Sphere – Homosexuality and Law 11 2.2 The Public Sphere – Homosexuality and Society 13 2.3 Dandyism, Aestheticism and Decadence 16 2.4 Oscar Wilde Performing Oscar Wilde 18 2.5 The Relationship of Oscar Wilde and Bosie Douglas 20 2.6 Loved Friend, Unloved Son - Lord Alfred Douglas 23 2.7 Beyond Boxing Rules - Lord Queensberry 25 3 The Trial within the Work of Oscar Wilde 29 3.1 Short summary of an almost dramatic trial 29 3.1.1 Prologue – Magistrates’ Court Proceedings 29 3.1.2 Act One – The Libel Trial 33 3.1.3 Act Two – The First Criminal Trial 36 3.1.4 Act Three – The Second Criminal Trial 39 3.2 The Trial Transcripts as Literary Artefacts 44 3.2.1 Staging a trial 44 3.2.2 Fiction but Facts - The Literary Evidence 48 3.2.2.1 The Priest and the Acolyte 49 3.2.2.2 Phrases and Philosophies 52 3.2.2.3 Dorian Gray 55 3.2.2.4 The Letters 60 3.2.2.5 Two Loves 62 3.2.3 Facts but Fiction – The Real Evidence 67 3.2.4 Review of a Performance – De Profundis 70 3.3 Placing the Transcripts in his Work 75 4 Conclusion 77 5 Appendix: Quotation from Dorian Gray 79 6 Bibliography 81 2 1 Introduction Wilde is still the Crown Prince of Bohemia. -

The Importance of Being Earnestly Independent

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNESTLY INDEPENDENT Gordon Turriff, Q. C. • 2012 MICH. ST. L. REv. 281 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. HOW OSCAR WILDE GOT THE WRONG ADVICE FROM HIS SOLICITOR ............................................................................................ 281 II. PROMOTING LAWYER INDEPENDENCE INTERNATIONALLY ................ 288 Ill. LAW SCHOOL INTEREST IN LAWYER INDEPENDENCE AND REGULATION OF LAWYERS .................................................................. 290 IV. LAWYER INDEPENDENCE, REGULATION OF LAWYERS, AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY ............................................................. 298 V. THE NEED TO ENCOURAGE A LAWYER INDEPENDENCE DEBATE ....... 302 I. HOW OSCAR WILDE GOT THE WRONG ADVICE FROM HIS SOLICITOR On Wednesday, April 6, 1881, in its judgment in Wheeler v. Le Marchant, 1 the English Court of Appeal confirmed that the "rule as to the non-production of communications between solicitor and client" had "been established upon grounds of general or public policy"2 "in order that . legal advice may be obtained safely and sufficiently."3 On Friday, March 1, * Mr. Turriff was called to the bar and admitted as a solicitor in British Columbia, Canada, in 1975. His field of practice is lawyer-client financial relationships and costs of litigation (attorney fee shifting). In 2009, he was the president of the Law Society of British Columbia. That society, which is not a lawyer advocacy group, regulates British Columbia lawyers in the public interest. Mr. Turriff is a founding member and director of the Interna tional Society for the Promotion of the Public Interest of Lawyer Independence. He acknowl edges the very fine assistance of his secretary, Marianne Stoody, who has contributed invalu ably to his work over the past five years. l. (1881) 17 Ch. D. 675 (C.A.). -

Jack Is a Feminist Issue

June/July 2018 No. 162 A Tribute to Katherine Amin Jack is a Feminist Issue MIICHAEL HAWLEY SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST: COLIN WILSON AT THE 1996 CONFERENCE HEATHER TWEED NINA and HOW BROWN JAN BONDESON THE BIG QUESTION VICTORIAN FICTION THE LATEST BOOK REVIEWS Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 162 June / July 2018 EDITORIAL: WHAT’S IN A NAME? Adam Wood JACK IS A FEMINIST ISSUE Katherine Amin THE NEW YORK WORLD’S E. TRACY GREAVES AND HIS SCOTLAND YARD INFORMANT Michael L Hawley THE BIG QUESTION Did the Police Know the Identity of the Ripper? Spotlight on Rippercast COLIN WILSON AT THE 1996 RIPPER CONFERENCE ZAZEL – THE HUMAN CANNONBALL Heather Tweed BEHIND BRASS BADGES AND IRON BARS Nina and Howard Brown FORD MADOX FORD, MURDER HOUSE DETECTIVE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: GLEAMS FROM THE DARK CONTINENT: THE WIZARD OF SWAZI SWAMP By Charles J Mansford Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement.