Lessons on Protest and Dissent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

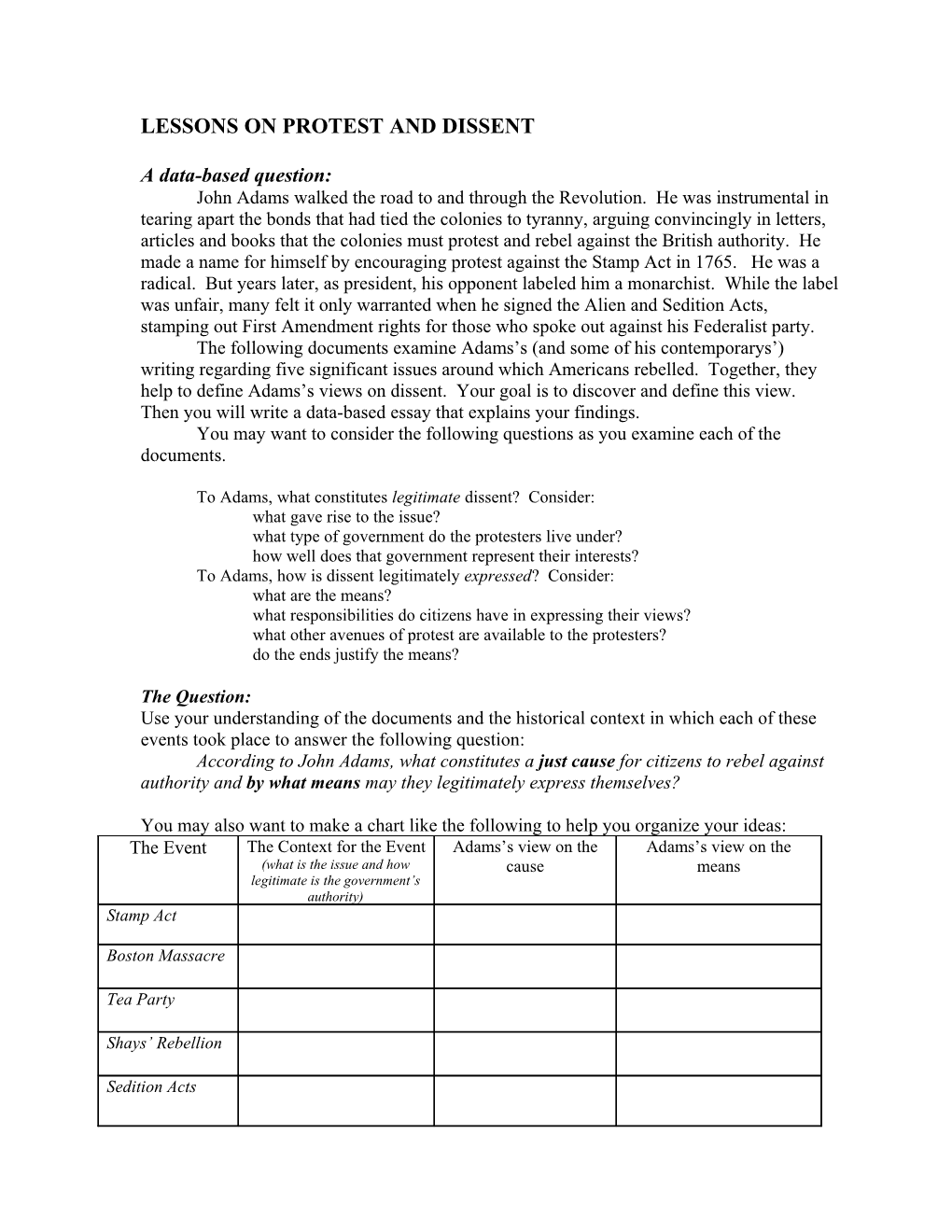

Recommended publications

-

The Federalist Era 1787-1800

THE FEDERALIST ERA 1787-1800 Articles of Confederation: the first form of government. *NATIONAL GOVERNMENT TOO WEAK! Too much state power “friendship of states” examples of being too weak: • No President/No executive • Congress can’t tax or raise an army • States are coining their own money • Foreign troubles (British on the frontier, French in New Orleans) Shays’ Rebellion: Daniel Shays is a farmer in Massachusetts protesting tax collectors. The rebellion is a wake up call - recognize we need a new government Constitutional Convention of 1787: Delegates meet to revise the Articles, instead draft a new Constitution • Major issue discussed = REPRESENTATION IN CONGRESS (more representatives in Congress, more influence you have in passing laws/policies in your favor) NJ Plan (equal per state) vs. Virginia Plan (based on population) House of Representatives: GREAT COMPROMISE Based on population Creates a bicameral Senate: (two-house) legislature Equal, two per state THREE-FIFTHS • 3 out of every 5 slaves will count for representation and taxation COMPROMISE • increases representation in Congress for South Other Compromises: • Congress regulates interstate and foreign trade COMMERCIAL • Can tax imports (tariffs) but not exports COMPROMISE • Slave trade continued until 1808 How did the Constitution fix the problems of the Articles of Confederation? ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION CONSTITUTION • States have the most power, national • states have some power, national government government has little has most • No President or executive to carry out -

John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and the Quasi-War with France

John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and the Quasi-War with France David Loudon General University Honors Professor Robert Griffith, Faculty Advisor American University, Spring 2010 1 John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and the Quasi-War with France Abstract This paper examines the split of the Federalist Party and subsequent election defeat in 1800 through the views of John Adams and Alexander Hamilton on the Quasi-War with France. More specifically, I will be focusing on what caused their split on the French issue. I argue that the main source of conflict between the two men was ideological differences on parties in contemporary American politics. While Adams believed that there were two parties in America and his job was to remain independent of both, Hamilton saw only one party (the Republicans), and believed that it was the goal of all “real” Americans to do whatever was needed to defeat that faction. This ideological difference between the two men resulted in their personal disdain for one another and eventually their split on the French issue. Introduction National politics in the early American republic was a very uncertain venture. The founding fathers had no historical precedents to rely upon. The kind of government created in the American constitution had never been attempted in the Western World; it was a piecemeal system designed in many ways more to gain individual state approval than for practical implementation. Furthermore, while the fathers knew they wanted opposition within their political system, they rejected political parties as evil and dangerous to the public good. This tension between the belief in opposition and the rejection of party sentiment led to confusion and high tensions during the early American republic. -

John Adams Contemporaries

17 150-163 Found2 AK 9/13/07 11:27 AM Page 150 Answer Key John Adams contemporaries. These students may point out that Adams penned defenses Handout A—John Adams of American rights in the 1770s and was (1735–1826) one of the earliest advocates of colonial 1. Adams played a leading role in the First independence from Great Britain. They Continental Congress, serving on ninety may also mention that his authorship committees and chairing twenty-five of of the Massachusetts Constitution and these.An early advocate of independence Declaration of Rights of 1780 makes from Great Britain, in 1776 he penned him a champion of individual liberty. his Thoughts on Government, describing 5. Some students may suggest that gov- how government should be arranged. ernment may limit speech when the He headed the committee charged public safety requires it. Others may with writing the Declaration of Inde- suggest that offensive or obscene pendence. He served on the commis- speech may be restricted. Still other sion that negotiated the Treaty of Paris, students will argue against any limita- which ended the Revolutionary War. tions on freedom of speech. 2. Adams was not present at the Consti- tutional Convention. However, while serving as an American diplomat in Handout B—Vocabulary and London, he followed the proceedings. Context Questions Adams and Jefferson urged Congress 1. Vocabulary to yield to the Anti-Federalist demand a. disagreed for the Bill of Rights as a condition for b. caused ratifying the proposed Constitution. c. until now 3. The Alien and Sedition Acts gave the d. -

Alien and Sedition Acts • Explain Significance of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions Do Now “The Vietnam War Was Lost in America

Adams SWBAT • Explain significance of the Alien and Sedition Acts • Explain significance of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions Do Now “The Vietnam War was lost in America. Public opinion killed any prospect of victory.” • What is the meaning of this statement? • What is more important, liberty (ie. free speech) or order (ie. security)? John Adams President John Adams • John Adams (Federalist) becomes President in 1797 *Due to an awkward feature of the Constitution, Jefferson becomes VP John Adams • During his presidency Adams passed the Alien and Sedition Acts • How does the cartoonist portray Adam’s actions? Alien and Sedition Acts, 1798 • Required immigrants to live in the Naturalization Act U.S. for l4 years before becoming a citizen • Allowed President to expel foreigners from the U.S. if he Alien Act believes they are dangerous to the nation's peace & safety • Allowed President to imprison or Alien Enemies Act expel foreigners considered dangerous in time of war • Barred American citizens from saying, writing, or publishing any Sedition Act false, scandalous, or malicious statements about the U.S. Gov, Congress, or the President Alien and Sedition Acts • The 4 acts together became known as the Alien and Sedition Acts • Response to the Alien and Sedition Acts: - Kentucky & Virginia Resolutions - (written by T. Jefferson & J. Madison) declared the Acts unconstitutional Virginia & Kentucky Resolutions 1. Called for the states to declare the Alien and Sedition Act null & void (invalid) 2. Introduced concept of nullification (ignoring -

Abigail Adams, Letters to from John Adams and John Quincy Adams

___Presented, and asterisked footnotes added, by the National Humanities Center for use in a Professional Development Seminar___ Mass. Hist. Soc. Mass. Hist. Soc. ABIGAIL ADAMS LETTERS TO HER SON JOHN QUINCY ADAMS 20 March 1780 Abigail Adams 26 December 1783 John Quincy Adams In Letters of Mrs. Adams, The Wife of John Adams, ed., Charles Francis Adams 3d. edition, Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841. 20 March, 1780. MY DEAR SON, Your letter, last evening received from Bilboa,* relieved me from much anxiety; for, having a day or two before received letters from your papa, Mr. Thaxter,1 and brother, in which packet I found none from you, nor any mention made of you, my mind, ever fruitful in conjectures, was instantly alarmed. I feared you were sick, unable to write, and your papa, unwilling to give me uneasiness, had concealed it from me; and this apprehension was confirmed by every person’s omitting to say how long they should continue in Bilboa. Your father’s letters came to Salem, yours to Newburyport, and soon gave ease to my anxiety, 10 at the same time that it excited gratitude and thankfulness to Heaven, for the preservation you all experienced in the imminent dangers which threatened you. You express in both your letters a degree of thankfulness. I hope it amounts to more than words, and that you will never be insensible to the particular preservation you have experienced in both your voyages. You have seen how inadequate the aid of man would have been, if the winds and the seas had not been under the particular government of * John Quincy Adams (13) and his younger brother Charles sailed to Europe in late 1779 with their father, John Adams, who had been appointed special envoy to Europe during the American Revolution. -

Massachusetts Historical Society, Adams Papers Editorial Project

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application, which conforms to a past set of grant guidelines. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the application guidelines for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Adams Papers Editorial Project Institution: Massachusetts Historical Society Project Director: Sara Martin Grant Program: Scholarly Editions and Translations Program Statement of Significance and Impact The Adams Papers Editorial Project is sponsored by and located at the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS). The Society’s 300,000-page Adams Family Papers manuscript collection, which spans more than a century of American history from the Revolutionary era to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, is consulted during the entire editing process, making the project unique among large-scale documentary editions. The Adams Papers has published 52 volumes to date and will continue to produce one volume per year. Free online access is provided by the MHS and the National Archives. -

Alien and Sedition Acts

• On your own, SILENTLY look at the three pictures and notate them as follows: • ! “reminds me of…” • ? “a question I have …” • * “an Ah-ha moment, or something interesting about the image is…” • With your partner, discuss your annotations. • Then, together write a summary statement of how this cartoon relates to the Alien and Sedition Acts. http://b1969d.medialib.glogster.com/media/8f36eeb83766a5f6047b82cfdb0e2b0c377d000ec198aab5deecb96deec3e660/sedition.jpg John Adams wins the election of 1796. • Thomas Jefferson becomes the Vice President. • The United States now has a Federalist President and a Republican Vice President. • The U.S. was in the middle of a dispute with France when Adams takes office. • President Adams would send diplomats to Paris to try to resolve the dispute. France was attacking U.S. shipping in route to England. Charles Pinkney, John Marshall, and Eldridge Gerry were U.S. Diplomats to France. 3 French envoys known as (X,Y, and Z) demanded a bribe of $250,000 to enter negotiations. The U.S. refused. The French government was corrupt and attacking U.S. merchants. The U.S. wanted war. 1797 - The XYZ Affair • In 1798 the United States stood on the brink of war with Alien and France. The Federalists believed that Democratic- Sedition Republican criticism of Federalist policies was disloyal Acts (1798) and feared that aliens (immigrants from France) living in the United States would sympathize with the French during a war. As a result, a Federalist-controlled Congress passed four laws, known collectively as the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws raised the residency requirements for citizenship from 5 to 14 years, authorized the President to deport aliens, and permitted their arrest, imprisonment, and deportation during wartime. -

American Principles of Self-Government

8 American Principles of Self-Government Michael Reber Introduction The prevailing modem way of handling exceptional moral con- duct is by categorizing it as supererogatory, where this is un- derstood to represent conduct that is morally good to do, but We have seen at the beginning of this new millennium a not morally bad not to do. But this means that exceptional moral test of the American Experiment. The corruption scandals of conduct is not required of anyone, which is to say that moral companies such as Enron, WorldCom, and their auditors development is not a moral requirement. Clearly this concep- Arthur Anderson, only highlight the greater problem of our tion of supererogatory conduct reinforces moral minimalism Republic in the 21" century—Modern Moral Minimalism. (p. 42). Modern Moral Minimalism is a moral system grounded in the ethics of realpolitik and classical liberalism. The most However, noblesse oblige is grounded in an ethics that Norton influential writers of realpolitik are Niccold Machiavelli terms eudaimonism or self-actualization. It holds that each (1947), Francis Bacon (1952), and Thomas Hobbes (1998). person is unique and each should discover whom one is (the On behalf of classical liberalism, John Locke (1988) is most daimon within) and actualize one's true potential to live the noted by scholars of political thought. Modern Moral good life within the congeniality and complementarity of Minimalism holds that we can only expect minimal moral excellences of fellow citizens (Norton, 1976). Thus, through conduct from all people. Machiavelli's moral code for princes the course of self-actualization, a person is obligated to live in Chapter XVIII of his classic work, The Prince, epitomizes up to individual expectations and the expectations of the this belief system: community. -

Chapter 6: Federalists and Republicans, 1789-1816

Federalists and Republicans 1789–1816 Why It Matters In the first government under the Constitution, important new institutions included the cabinet, a system of federal courts, and a national bank. Political parties gradually developed from the different views of citizens in the Northeast, West, and South. The new government faced special challenges in foreign affairs, including the War of 1812 with Great Britain. The Impact Today During this period, fundamental policies of American government came into being. • Politicians set important precedents for the national government and for relations between the federal and state governments. For example, the idea of a presidential cabinet originated with George Washington and has been followed by every president since that time • President Washington’s caution against foreign involvement powerfully influenced American foreign policy. The American Vision Video The Chapter 6 video, “The Battle of New Orleans,” focuses on this important event of the War of 1812. 1804 • Lewis and Clark begin to explore and map 1798 Louisiana Territory 1789 • Alien and Sedition • Washington Acts introduced 1803 elected • Louisiana Purchase doubles president ▲ 1794 size of the nation Washington • Jay’s Treaty signed J. Adams Jefferson 1789–1797 ▲ 1797–1801 ▲ 1801–1809 ▲ ▲ 1790 1797 1804 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1793 1794 1805 • Louis XVI guillotined • Polish rebellion • British navy wins during French suppressed by Battle of Trafalgar Revolution Russians 1800 • Beethoven’s Symphony no. 1 written 208 Painter and President by J.L.G. Ferris 1812 • United States declares 1807 1811 war on Britain • Embargo Act blocks • Battle of Tippecanoe American trade with fought against Tecumseh 1814 Britain and France and his confederacy • Hartford Convention meets HISTORY Madison • Treaty of Ghent signed ▲ 1809–1817 ▲ ▲ ▲ Chapter Overview Visit the American Vision 1811 1818 Web site at tav.glencoe.com and click on Chapter ▼ ▼ ▼ Overviews—Chapter 6 to 1808 preview chapter information. -

"Bound Fast and Brought Under the Yokes": John Adams and the Regulation of Privacy at the Founding

Fordham Law Review Volume 72 Issue 6 Article 3 2004 "Bound Fast and Brought Under the Yokes": John Adams and the Regulation of Privacy at the Founding Allison L. LaCroix Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Allison L. LaCroix, "Bound Fast and Brought Under the Yokes": John Adams and the Regulation of Privacy at the Founding, 72 Fordham L. Rev. 2331 (2004). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol72/iss6/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE "BOUND FAST AND BROUGHT UNDER THE YOKE": JOHN ADAMS AND THE REGULATION OF PRIVACY AT THE FOUNDING Alison L. LaCroix* The announcement of the United States Supreme Court in 1965 that a right to privacy existed, and that it predated the Bill of Rights, launched a historical and legal quest to sound the origins and extent of the right that has continued to the present day.' Legal scholars quickly grasped hold of the new star in the constitutional firmament, producing countless books and articles examining the caselaw pedigree and the potential scope of this right to privacy. Historians, however, have for the most part shied away from tracing the origins of the right to privacy, perhaps hoping to avoid the ignominy of practicing "law-office history."' Instead, some historians have engaged in subtle searches for markers of privacy-such as an emphasis on family,3 a notion of the home as an oasis,4 or a minimal * Doctoral candidate, Department of History, Harvard University. -

The First and the Second

The First and the Second ____________________________ Kah Kin Ho APPROVED: ____________________________ Alin Fumurescu, Ph.D. Committee Chair ___________________________ Jeremy D. Bailey, Ph.D. __________________________ Jeffrey Church, Ph.D. ________________________________ Antonio D. Tillis, Ph.D. Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Hispanic Studies The Second and the First, An Examination into the Formation of the First Official Political Parties Under John Adams Kah Kin Ho Current as of 1 May, 2020 2 Introduction A simple inquiry into the cannon of early American history would reveal that most of the scholarly work done on the presidency of John Adams has mostly been about two things. The first, are the problems associated with his “characteristic stubbornness” and his tendencies to be politically isolated (Mayville, 2016, pg. 128; Ryerson, 2016, pg. 350). The second, is more preoccupied with his handling of foreign relations, since Adams was seemingly more interested in those issues than the presidents before and after him (DeConde, 1966, pg. 7; Elkin and McKitrick, 1993, pg. 529). But very few have attempted to examine the correlation between the two, or even the consequences the two collectively considered would have domestically. In the following essay, I will attempt to do so. By linking the two, I will try to show that because of these two particularities, he ultimately will— however unintentionally— contribute substantially to the development of political parties and populism. In regard to his personality, it is often thought that he was much too ambitious and self- righteous to have been an ideal president in the first place. -

The “Common Sense” of Adams the Establishment of an Independent Judiciary

Country I would cheerfully retire from public life forever, renounce all Chance for Profits or Honors from the public, nay I would cheerfully contribute my little Property to obtain Peace and Liberty. — But all these must go and my Life too before I can surrender the Right of my Country Constitutionally Sound Adams had recently returned from France in 1779 to a free Constitution. when he was selected as a delegate to the Massachusetts constitutional convention and asked to write the draft constitution for the —John Adams to Abigail Adams, October 7, 1775 state. The Massachusetts Constitution remains the oldest functioning written constitution in the world to this day. The document echoed (Above) The Massachusetts Constitution, many of Adams’s recommendations in his earlier 1780. Boston Public Library, Rare Books Thoughts on Government, particularly the & Manuscripts Department. (Below) Constitutions des Treize Etats-Unis separation and balance of political powers and de l’Amerique, 1783. The John Adams Library The “Common Sense” of Adams the establishment of an independent judiciary. at the Boston Public Library. The most famous pamphlet of the American Revolution, Common Sense was written by The title page includes an image of Englishman Thomas Paine in early 1776 as a the Great Seal of the United States, provocative call to action for the colonies to John Adams purchased two which had been recently adopted copies of Common Sense en route by the Continental Congress in June declare their independence from Britain. First to the Continental Congress in 1782. It is the seal’s first known use published anonymously, Common Sense was Philadelphia in February, 1776, and in a printed book.