Abigail Adams, Letters to from John Adams and John Quincy Adams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and the Quasi-War with France

John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and the Quasi-War with France David Loudon General University Honors Professor Robert Griffith, Faculty Advisor American University, Spring 2010 1 John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and the Quasi-War with France Abstract This paper examines the split of the Federalist Party and subsequent election defeat in 1800 through the views of John Adams and Alexander Hamilton on the Quasi-War with France. More specifically, I will be focusing on what caused their split on the French issue. I argue that the main source of conflict between the two men was ideological differences on parties in contemporary American politics. While Adams believed that there were two parties in America and his job was to remain independent of both, Hamilton saw only one party (the Republicans), and believed that it was the goal of all “real” Americans to do whatever was needed to defeat that faction. This ideological difference between the two men resulted in their personal disdain for one another and eventually their split on the French issue. Introduction National politics in the early American republic was a very uncertain venture. The founding fathers had no historical precedents to rely upon. The kind of government created in the American constitution had never been attempted in the Western World; it was a piecemeal system designed in many ways more to gain individual state approval than for practical implementation. Furthermore, while the fathers knew they wanted opposition within their political system, they rejected political parties as evil and dangerous to the public good. This tension between the belief in opposition and the rejection of party sentiment led to confusion and high tensions during the early American republic. -

Massachusetts Historical Society, Adams Papers Editorial Project

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application, which conforms to a past set of grant guidelines. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the application guidelines for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Adams Papers Editorial Project Institution: Massachusetts Historical Society Project Director: Sara Martin Grant Program: Scholarly Editions and Translations Program Statement of Significance and Impact The Adams Papers Editorial Project is sponsored by and located at the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS). The Society’s 300,000-page Adams Family Papers manuscript collection, which spans more than a century of American history from the Revolutionary era to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, is consulted during the entire editing process, making the project unique among large-scale documentary editions. The Adams Papers has published 52 volumes to date and will continue to produce one volume per year. Free online access is provided by the MHS and the National Archives. -

American Principles of Self-Government

8 American Principles of Self-Government Michael Reber Introduction The prevailing modem way of handling exceptional moral con- duct is by categorizing it as supererogatory, where this is un- derstood to represent conduct that is morally good to do, but We have seen at the beginning of this new millennium a not morally bad not to do. But this means that exceptional moral test of the American Experiment. The corruption scandals of conduct is not required of anyone, which is to say that moral companies such as Enron, WorldCom, and their auditors development is not a moral requirement. Clearly this concep- Arthur Anderson, only highlight the greater problem of our tion of supererogatory conduct reinforces moral minimalism Republic in the 21" century—Modern Moral Minimalism. (p. 42). Modern Moral Minimalism is a moral system grounded in the ethics of realpolitik and classical liberalism. The most However, noblesse oblige is grounded in an ethics that Norton influential writers of realpolitik are Niccold Machiavelli terms eudaimonism or self-actualization. It holds that each (1947), Francis Bacon (1952), and Thomas Hobbes (1998). person is unique and each should discover whom one is (the On behalf of classical liberalism, John Locke (1988) is most daimon within) and actualize one's true potential to live the noted by scholars of political thought. Modern Moral good life within the congeniality and complementarity of Minimalism holds that we can only expect minimal moral excellences of fellow citizens (Norton, 1976). Thus, through conduct from all people. Machiavelli's moral code for princes the course of self-actualization, a person is obligated to live in Chapter XVIII of his classic work, The Prince, epitomizes up to individual expectations and the expectations of the this belief system: community. -

"Bound Fast and Brought Under the Yokes": John Adams and the Regulation of Privacy at the Founding

Fordham Law Review Volume 72 Issue 6 Article 3 2004 "Bound Fast and Brought Under the Yokes": John Adams and the Regulation of Privacy at the Founding Allison L. LaCroix Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Allison L. LaCroix, "Bound Fast and Brought Under the Yokes": John Adams and the Regulation of Privacy at the Founding, 72 Fordham L. Rev. 2331 (2004). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol72/iss6/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE "BOUND FAST AND BROUGHT UNDER THE YOKE": JOHN ADAMS AND THE REGULATION OF PRIVACY AT THE FOUNDING Alison L. LaCroix* The announcement of the United States Supreme Court in 1965 that a right to privacy existed, and that it predated the Bill of Rights, launched a historical and legal quest to sound the origins and extent of the right that has continued to the present day.' Legal scholars quickly grasped hold of the new star in the constitutional firmament, producing countless books and articles examining the caselaw pedigree and the potential scope of this right to privacy. Historians, however, have for the most part shied away from tracing the origins of the right to privacy, perhaps hoping to avoid the ignominy of practicing "law-office history."' Instead, some historians have engaged in subtle searches for markers of privacy-such as an emphasis on family,3 a notion of the home as an oasis,4 or a minimal * Doctoral candidate, Department of History, Harvard University. -

The “Common Sense” of Adams the Establishment of an Independent Judiciary

Country I would cheerfully retire from public life forever, renounce all Chance for Profits or Honors from the public, nay I would cheerfully contribute my little Property to obtain Peace and Liberty. — But all these must go and my Life too before I can surrender the Right of my Country Constitutionally Sound Adams had recently returned from France in 1779 to a free Constitution. when he was selected as a delegate to the Massachusetts constitutional convention and asked to write the draft constitution for the —John Adams to Abigail Adams, October 7, 1775 state. The Massachusetts Constitution remains the oldest functioning written constitution in the world to this day. The document echoed (Above) The Massachusetts Constitution, many of Adams’s recommendations in his earlier 1780. Boston Public Library, Rare Books Thoughts on Government, particularly the & Manuscripts Department. (Below) Constitutions des Treize Etats-Unis separation and balance of political powers and de l’Amerique, 1783. The John Adams Library The “Common Sense” of Adams the establishment of an independent judiciary. at the Boston Public Library. The most famous pamphlet of the American Revolution, Common Sense was written by The title page includes an image of Englishman Thomas Paine in early 1776 as a the Great Seal of the United States, provocative call to action for the colonies to John Adams purchased two which had been recently adopted copies of Common Sense en route by the Continental Congress in June declare their independence from Britain. First to the Continental Congress in 1782. It is the seal’s first known use published anonymously, Common Sense was Philadelphia in February, 1776, and in a printed book. -

John Quincy Adams Influence on Washington's Farewell Address: A

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Undergraduate Research La Salle Scholar Winter 1-7-2019 John Quincy Adams Influence on ashingtW on’s Farewell Address: A Critical Examination Stephen Pierce La Salle University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/undergraduateresearch Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, Military History Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, National Security Law Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pierce, Stephen, "John Quincy Adams Influence on ashingtW on’s Farewell Address: A Critical Examination" (2019). Undergraduate Research. 33. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/undergraduateresearch/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle Scholar at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John Quincy Adams Influence on Washington’s Farewell Address: A Critical Examination By Stephen Pierce In the last official letter to President Washington as Minister to the Netherlands in 1797, John Quincy Adams expressed his deepest thanks and reverence for the appointment that was bestowed upon him by the chief executive. As Washington finished his second and final term in office, Adams stated, “I shall always consider my personal obligations to you among the strongest motives to animate my industry and invigorate my exertions in the service of my country.” After his praise to Washington, he went into his admiration of the president’s 1796 Farewell Address. -

Part 1 John Adams, Sr., Generation 7

Part 1 John Adams, Sr., Generation 7 General Background The finding and researching of our John Adams has been long and enduring, but edifying and rewarding with, the undertaking stretching over 15 years. This account may be in essential error if early dates of arrival to the Colonies prove to be incorrect. My initial premise shows that John and his son were indentured servants to Thomas Proctor in 1771 as shown on pages 3-4. As of this writing the earliest documentation of my Adams family dates back to colonial days of pre-revolutionary America. I show our John Adams, Sen’r, (as he wrote) likely born about 1730, believed to be married to a Hamilton. His son, John, Jun’r., is shown to have been born in Northern Ireland in 1765 according to Butler County historical records. This would indicate that John was 35 years old when John was born. John Sen’r, his wife and son were all living in Washington Township of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania as indicated both in census and in Revolutionary War records. Land records will indicate that John Sr. and his family were living upon this land in 1773 when he was 43 and John Jr. was but 8 years of age. There were numerous Indian skirmishes and battles fueled by the English that required the building of high walled forts to offer protection for families. As farmers, hunters and trappers, the early Presbyterian Scottish pioneers such as the Adams’ were highly skilled in the essential requirements of survival. John and his son both fought in the Revolutionary War for the freedoms we all share today. -

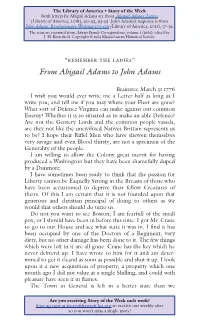

From Abigail Adams to John Adams

The Library of America • Story of the Week Both letters by Abigail Adams are from Abigail Adams: Letters (Library of America, 2016), 90–93, 93–95. John Adams’s response is from John Adams: Revolutionary Writings 1775–1783 (Library of America, 2011), 57–59. The texts are reprinted from Adams Family Correspondence, volume 1 (1963), edited by J. H. Butterfield. Copyright © 1963 Massachusetts Historical Society. “REMEMBER THE LADIES” From Abigail Adams to John Adams Braintree March 31 1776 I wish you would ever write me a Letter half as long as I write you; and tell me if you may where your Fleet are gone? What sort of Defence Virginia can make against our common Enemy? Whether it is so situated as to make an able Defence? Are not the Gentery Lords and the common people vassals, are they not like the uncivilized Natives Brittain represents us to be? I hope their Riffel Men who have shewen themselves very savage and even Blood thirsty; are not a specimen of the Generality of the people. I am willing to allow the Colony great merrit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore. I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Eaquelly Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us. Do not you want to see Boston; I am fearfull of the small pox, or I should have been in before this time. -

Guide to the John Quincy Adams Collection, 1802-1848

Bridgewater State University Maxwell Library Archives & Special Collections John Quincy Adams Collection, 1802-1848 (MSS-020) Finding Aid Compiled by Orson Kingsley, 2018 Last Updated: May 12, 2020 Maxwell Library Bridgewater State University 10 Shaw Road / Bridgewater, MA 02325 / (508) 531-1389 Finding Aid: John Quincy Adams (MSS-020) 2 Volume: 1.75 linear feet (9 document boxes containing 58 pamphlets) Acquisition: Nearly all items in this manuscript group were donated to Bridgewater State University by Jordan Fiore. Access: Access to this record group is unrestricted. Copyright: The researcher assumes full responsibility for conforming with the laws of copyright. Whenever possible, the Maxwell Library will provide information about copyright owners and other restrictions, but the legal determination ultimately rests with the researcher. Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be discussed with the University Archivist. John Quincy Adams Biographical Sketch John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) was the sixth president of the United States from 1825-1829. He had a long and fruitful career in public service, including positions such as American statesman and diplomat, ambassador to foreign nations, United States Senator and House Representative from Massachusetts, and more. He was the son of John Adams, the second president of the United States. Adams was a strong supporter of social reform, with some of the areas of specific interest being public education, abolition, and temperance. A number of the pamphlets in this collection represent his thoughts on these issues. John Quincy Adams Scope and Content Note This collection consists of published pamphlets of speeches and writings. Most are from John Quincy Adams, and a number of others are from his father, John Adams, and Timothy Pickering, an adversary of both John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams. -

Dna and the Jewish Ancestry of John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton

Journal of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JLAH) Issue: Vol. 2; No. 4; April 2020 pp. 10-18 ISSN 2690-070X (Print) 2690-0718 (Online) Website: www.jlahnet.com E-mail: [email protected] Doi: 10.48150/jlah.v2no4.2021.a2 DNA AND THE JEWISH ANCESTRY OF JOHN ADAMS, THOMAS JEFFERSON AND ALEXANDER HAMILTON Elizabeth C. Hirschman Hill Richmond Professor of Business Department of Business and Economics University of Virginia-Wise E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This research investigates the ancestry of Presidents John and John Quincy Adams, Thomas Jefferson and patriot Alexander Hamilton. Using ancestral DNA tracing and global DNA data-bases, we show that these four men, critical to the early political and economic development of the United States, were likely of Jewish ancestry. This finding casts doubt on the Protestant, Anglo-Saxon origins of American cultural ideology. Keywords: Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Genealogical DNA, Jewish Ancestry Introduction American history books consistently assume that the country’s early leaders were uniformly of British Protestant ancestry – giving rise to an ideology of White Protestant Supremacy that is pervasive in American culture to the present day. The present research calls this central assumption into question by examining the ancestry of three Presidents – Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and John Quincy Adams – and one of the central political thinkers and financial leaders of the early republic –Alexander Hamilton. In all four cases genealogical DNA samples tie these men to recent Jewish ancestors. This calls into question the ideology of White Protestant Supremacy and indicates that early American patriots were of more diverse ethnicity than previously believed. -

John Adams Thomas Jefferson Physical Characteristics

Working With Comparisons: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and the Rhetoric and Art of the American Revolution From HBO’s John Adams mini-series based on the biography by David McCullough Episode 1: “Join or Die” (The Boston Massacre) 1 C. Barrera 2012 Name ________________________________________ Date _______________ Class _________________ Viewing Guide- John Adams (miniseries) Episode 1- “Join or Die” Boston 1770 1. What is the significance of the “Tory” sign on the skeleton hanging off the trees in the opening sequence? 2. Characterize John and Abigail Adam’s relationship when Abigail looks at John and immediately knows that he has lost his case. 3. Characterize John Adams as a father. 4. John Adams hears a distant crowd yell, “fire!” What does John initially think this is? 5. Describe Samuel Adams’ reaction to the massacre. 6. What is the significance about Crispus Attucks death? 7. Why was the bloodied visitor at the Adams’ house? Speculate why he was bloodied. 8. What warning does Abigail Adams give John Adams about defending Captain Preston? 9. Explain Abigail Adams statement, “They will say you are the Crown’s man!” 2 C. Barrera 2012 10. What is Captain Wilson’s explanation for the massacre? 11. What is Sam Adams’ political motive for having a procession after the massacre? 12. Contrast Paul Revere’s sketch of the Boston massacre with reality. 13. Explain Abigail Adam’s comment to John, “Mask your intelligence with more patience than those less intelligent that you.” 14. Mr. Goddard, the first witness, admits the crowd carried clubs. Why does he admit this? 15. -

Cultural Landscape Report: Adams National Historic Site

Cultural Landscape Report Adams National Historic Site Qiincy, Massachusetts Illustrated Site Chronology United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation 99 Warren Street Brookline, Massachusetts 02146 IN REPLY REFER TO: January 12, 1998 Memorandum To: Superintendent, Adams National Historic Site From: Director, Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation Subject: Transmittal of Cultural Landscape Report for Adams National Historic Site I am pleased to enclose a copy of Cultural Landscape Report: Illustrated Site Chronology for Adams National Historic Site. The report is the result of historical research of the cultural landscape, reflecting a century-and-a-half of Adams family ownership and management. As agreed in discussions with you and your staff, the document presents illustrations integrated with a narrative site chronology, a format that provides an accessible summary of the site's history. • The report was completed by Katharine Lacy, Historical Landscape Architect with the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation; the editing and design were produced with Beth McKinney of Graphic Design and Shary Page Berg with Goody Clancy & Associates. We have published this report as part of the Olmsted Center's Cultural Landscape Publication Series. At part of the series, the Government Printing Office has printed and distributed copies of this report to 500 libraries across the country. We are sending 100 copies of the report for the Adams National Historic Site under separate cover. As required by NPS-28, the Cultural Resource Management Guidelines, we have also transmitted copies to the attached list of offices. If you have any comments or questions, please contact me at the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation (617) 566-1689 x 267.