"Bound Fast and Brought Under the Yokes": John Adams and the Regulation of Privacy at the Founding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and the Quasi-War with France

John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and the Quasi-War with France David Loudon General University Honors Professor Robert Griffith, Faculty Advisor American University, Spring 2010 1 John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and the Quasi-War with France Abstract This paper examines the split of the Federalist Party and subsequent election defeat in 1800 through the views of John Adams and Alexander Hamilton on the Quasi-War with France. More specifically, I will be focusing on what caused their split on the French issue. I argue that the main source of conflict between the two men was ideological differences on parties in contemporary American politics. While Adams believed that there were two parties in America and his job was to remain independent of both, Hamilton saw only one party (the Republicans), and believed that it was the goal of all “real” Americans to do whatever was needed to defeat that faction. This ideological difference between the two men resulted in their personal disdain for one another and eventually their split on the French issue. Introduction National politics in the early American republic was a very uncertain venture. The founding fathers had no historical precedents to rely upon. The kind of government created in the American constitution had never been attempted in the Western World; it was a piecemeal system designed in many ways more to gain individual state approval than for practical implementation. Furthermore, while the fathers knew they wanted opposition within their political system, they rejected political parties as evil and dangerous to the public good. This tension between the belief in opposition and the rejection of party sentiment led to confusion and high tensions during the early American republic. -

Abigail Adams, Letters to from John Adams and John Quincy Adams

___Presented, and asterisked footnotes added, by the National Humanities Center for use in a Professional Development Seminar___ Mass. Hist. Soc. Mass. Hist. Soc. ABIGAIL ADAMS LETTERS TO HER SON JOHN QUINCY ADAMS 20 March 1780 Abigail Adams 26 December 1783 John Quincy Adams In Letters of Mrs. Adams, The Wife of John Adams, ed., Charles Francis Adams 3d. edition, Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841. 20 March, 1780. MY DEAR SON, Your letter, last evening received from Bilboa,* relieved me from much anxiety; for, having a day or two before received letters from your papa, Mr. Thaxter,1 and brother, in which packet I found none from you, nor any mention made of you, my mind, ever fruitful in conjectures, was instantly alarmed. I feared you were sick, unable to write, and your papa, unwilling to give me uneasiness, had concealed it from me; and this apprehension was confirmed by every person’s omitting to say how long they should continue in Bilboa. Your father’s letters came to Salem, yours to Newburyport, and soon gave ease to my anxiety, 10 at the same time that it excited gratitude and thankfulness to Heaven, for the preservation you all experienced in the imminent dangers which threatened you. You express in both your letters a degree of thankfulness. I hope it amounts to more than words, and that you will never be insensible to the particular preservation you have experienced in both your voyages. You have seen how inadequate the aid of man would have been, if the winds and the seas had not been under the particular government of * John Quincy Adams (13) and his younger brother Charles sailed to Europe in late 1779 with their father, John Adams, who had been appointed special envoy to Europe during the American Revolution. -

Massachusetts Historical Society, Adams Papers Editorial Project

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application, which conforms to a past set of grant guidelines. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the application guidelines for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Adams Papers Editorial Project Institution: Massachusetts Historical Society Project Director: Sara Martin Grant Program: Scholarly Editions and Translations Program Statement of Significance and Impact The Adams Papers Editorial Project is sponsored by and located at the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS). The Society’s 300,000-page Adams Family Papers manuscript collection, which spans more than a century of American history from the Revolutionary era to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, is consulted during the entire editing process, making the project unique among large-scale documentary editions. The Adams Papers has published 52 volumes to date and will continue to produce one volume per year. Free online access is provided by the MHS and the National Archives. -

American Principles of Self-Government

8 American Principles of Self-Government Michael Reber Introduction The prevailing modem way of handling exceptional moral con- duct is by categorizing it as supererogatory, where this is un- derstood to represent conduct that is morally good to do, but We have seen at the beginning of this new millennium a not morally bad not to do. But this means that exceptional moral test of the American Experiment. The corruption scandals of conduct is not required of anyone, which is to say that moral companies such as Enron, WorldCom, and their auditors development is not a moral requirement. Clearly this concep- Arthur Anderson, only highlight the greater problem of our tion of supererogatory conduct reinforces moral minimalism Republic in the 21" century—Modern Moral Minimalism. (p. 42). Modern Moral Minimalism is a moral system grounded in the ethics of realpolitik and classical liberalism. The most However, noblesse oblige is grounded in an ethics that Norton influential writers of realpolitik are Niccold Machiavelli terms eudaimonism or self-actualization. It holds that each (1947), Francis Bacon (1952), and Thomas Hobbes (1998). person is unique and each should discover whom one is (the On behalf of classical liberalism, John Locke (1988) is most daimon within) and actualize one's true potential to live the noted by scholars of political thought. Modern Moral good life within the congeniality and complementarity of Minimalism holds that we can only expect minimal moral excellences of fellow citizens (Norton, 1976). Thus, through conduct from all people. Machiavelli's moral code for princes the course of self-actualization, a person is obligated to live in Chapter XVIII of his classic work, The Prince, epitomizes up to individual expectations and the expectations of the this belief system: community. -

Agriculture in the Fredericksburg Area Harold J

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 6-1969 Agriculture in the Fredericksburg area Harold J. Muddiman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Muddiman, Harold J., "Agriculture in the Fredericksburg area" (1969). Master's Theses. Paper 823. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AGRICULTURE IN THE FREDERICKSBURG AREA, 1800 TO 1840 BY HAROLD J. MUDDIMAN, JR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDA CY FOR THE DEGREE OF MP.STER OF ARTS IN HISTORY JUNE 1969 _j- \.-'.' S I ,, I 1 \ f ! '• '\ ~ 4' ·.,; " '''"·. ·-' Approved: PREFACE I would like to express my appreciation for the invaluable advice of Dr. Joseph C. Robert in the preparation of this paper. Thanks also to my wife, Jane, for her help in gathering information from various county tax records. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. AGRICULTURAL CONDITIONS 1 Introduction Description of Agriculture in Virginia Tobacco Wheat Corn Cotton Flax, Hemp Livestock Landholdings II. PROBLEMS FOR THE FARMER . ' . 26 Slavery Overseer Transportation Tariff Emigration III. AGRICULTURAL REFORM 43 John Taylor of Caroline Diversified Farming Agricultural Societies Agricultural Journals Manures Crop Rotation Improved Agricultural Implements IV. CONCLUSION 68 BIBLIOGRAPHY 69 VITA LIST OF TABLES TABLE PAGE I. Tobacco Shipped From Fredericksburg and Nalmouth Warehouses, 1800-1824 ......... -

The “Common Sense” of Adams the Establishment of an Independent Judiciary

Country I would cheerfully retire from public life forever, renounce all Chance for Profits or Honors from the public, nay I would cheerfully contribute my little Property to obtain Peace and Liberty. — But all these must go and my Life too before I can surrender the Right of my Country Constitutionally Sound Adams had recently returned from France in 1779 to a free Constitution. when he was selected as a delegate to the Massachusetts constitutional convention and asked to write the draft constitution for the —John Adams to Abigail Adams, October 7, 1775 state. The Massachusetts Constitution remains the oldest functioning written constitution in the world to this day. The document echoed (Above) The Massachusetts Constitution, many of Adams’s recommendations in his earlier 1780. Boston Public Library, Rare Books Thoughts on Government, particularly the & Manuscripts Department. (Below) Constitutions des Treize Etats-Unis separation and balance of political powers and de l’Amerique, 1783. The John Adams Library The “Common Sense” of Adams the establishment of an independent judiciary. at the Boston Public Library. The most famous pamphlet of the American Revolution, Common Sense was written by The title page includes an image of Englishman Thomas Paine in early 1776 as a the Great Seal of the United States, provocative call to action for the colonies to John Adams purchased two which had been recently adopted copies of Common Sense en route by the Continental Congress in June declare their independence from Britain. First to the Continental Congress in 1782. It is the seal’s first known use published anonymously, Common Sense was Philadelphia in February, 1776, and in a printed book. -

John Quincy Adams Influence on Washington's Farewell Address: A

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Undergraduate Research La Salle Scholar Winter 1-7-2019 John Quincy Adams Influence on ashingtW on’s Farewell Address: A Critical Examination Stephen Pierce La Salle University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/undergraduateresearch Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, Military History Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, National Security Law Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pierce, Stephen, "John Quincy Adams Influence on ashingtW on’s Farewell Address: A Critical Examination" (2019). Undergraduate Research. 33. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/undergraduateresearch/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle Scholar at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John Quincy Adams Influence on Washington’s Farewell Address: A Critical Examination By Stephen Pierce In the last official letter to President Washington as Minister to the Netherlands in 1797, John Quincy Adams expressed his deepest thanks and reverence for the appointment that was bestowed upon him by the chief executive. As Washington finished his second and final term in office, Adams stated, “I shall always consider my personal obligations to you among the strongest motives to animate my industry and invigorate my exertions in the service of my country.” After his praise to Washington, he went into his admiration of the president’s 1796 Farewell Address. -

Part 1 John Adams, Sr., Generation 7

Part 1 John Adams, Sr., Generation 7 General Background The finding and researching of our John Adams has been long and enduring, but edifying and rewarding with, the undertaking stretching over 15 years. This account may be in essential error if early dates of arrival to the Colonies prove to be incorrect. My initial premise shows that John and his son were indentured servants to Thomas Proctor in 1771 as shown on pages 3-4. As of this writing the earliest documentation of my Adams family dates back to colonial days of pre-revolutionary America. I show our John Adams, Sen’r, (as he wrote) likely born about 1730, believed to be married to a Hamilton. His son, John, Jun’r., is shown to have been born in Northern Ireland in 1765 according to Butler County historical records. This would indicate that John was 35 years old when John was born. John Sen’r, his wife and son were all living in Washington Township of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania as indicated both in census and in Revolutionary War records. Land records will indicate that John Sr. and his family were living upon this land in 1773 when he was 43 and John Jr. was but 8 years of age. There were numerous Indian skirmishes and battles fueled by the English that required the building of high walled forts to offer protection for families. As farmers, hunters and trappers, the early Presbyterian Scottish pioneers such as the Adams’ were highly skilled in the essential requirements of survival. John and his son both fought in the Revolutionary War for the freedoms we all share today. -

VOLUME XVL-NO. 39. MEDICAL. Fmml HAHRISONBURO, VA., THURSDAY JULY T, 1H81. Iieilfflsl, Neuralgia, Sciatica, Lumbago, Backache, S

VOLUME XVL-NO. 39. HAHRISONBURO, VA., THURSDAY JULY T, 1H81. TERMS:—$2.()() A YEAH. MEDICAL. IFrom the Washington Sunday Herald.] of the North and South, and after the pas- Marshall Was the eldest son of Thomas What an immortal epitaph 1 It might vity, and control of men. He was six ground is that of the Wilderness, where have been added, that ho was the third times Speaker of the House of Representa- THE CLASSIC TBIAtiGLE. sage of the ordinance of secession by the Marshall, a tiative of Wales, and Mary Generals R. K. Leo and U. S. Grant crossed State of Virginia, and the organization of Keith. He entered the army of General President of the United States; Washing- tives; many years United States Senator, swords for the first time, for several days, BY BIXIK ORET. fhe Southern Confederacy, the Confederate Washington with his father, who wdd Col- ton's Secretary of State; Governor of Vir- and Secretary of State under tlio adminis- in May, 1864. flag, the emblem of a separate nationality onel of the 8d Virginia regimtntt; and ginia ; Minister to France; the piirclmscr of tration of John Quincy Adams. In this county was bora and reared Chas. fmml ■What 18 "7 As OUusie Triangle f" Wc and a dissevered union of the States, could served during a part of the war oh the Lonisiana; the destroyer of the Allen and Mr. Clay was the author of three compro- Fenton Mercer, a distinguished politician, will try and explain. To traverse it you be seen from the Capitol and White ftouso. -

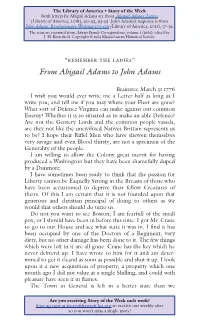

From Abigail Adams to John Adams

The Library of America • Story of the Week Both letters by Abigail Adams are from Abigail Adams: Letters (Library of America, 2016), 90–93, 93–95. John Adams’s response is from John Adams: Revolutionary Writings 1775–1783 (Library of America, 2011), 57–59. The texts are reprinted from Adams Family Correspondence, volume 1 (1963), edited by J. H. Butterfield. Copyright © 1963 Massachusetts Historical Society. “REMEMBER THE LADIES” From Abigail Adams to John Adams Braintree March 31 1776 I wish you would ever write me a Letter half as long as I write you; and tell me if you may where your Fleet are gone? What sort of Defence Virginia can make against our common Enemy? Whether it is so situated as to make an able Defence? Are not the Gentery Lords and the common people vassals, are they not like the uncivilized Natives Brittain represents us to be? I hope their Riffel Men who have shewen themselves very savage and even Blood thirsty; are not a specimen of the Generality of the people. I am willing to allow the Colony great merrit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore. I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Eaquelly Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us. Do not you want to see Boston; I am fearfull of the small pox, or I should have been in before this time. -

Property Rights in John Marshall's Virginia: the Case of Crenshaw and Crenshaw V

UIC Law Review Volume 33 Issue 4 Article 22 Summer 2000 Property Rights in John Marshall's Virginia: The Case of Crenshaw and Crenshaw v. Slate River Company, 33 J. Marshall L. Rev. 1175 (2000) J. Gordon Hylton Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Judges Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Profession Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation J. Gordon Hylton, Property Rights in John Marshall's Virginia: The Case of Crenshaw and Crenshaw v. Slate River Company, 33 J. Marshall L. Rev. 1175 (2000) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol33/iss4/22 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROPERTY RIGHTS IN JOHN MARSHALL'S VIRGINIA: THE CASE OF CRENSHAW AND CRENSHAW V. SLATE RIVER COMPANY J. GORDON HYLTON* As Jim Ely has reminded us, historians have long associated John Marshall with the twin causes of constitutional nationalism and the protection of property rights.! However, it would be a mistake to assume that these two concepts were inseparable or that it was Marshall's embrace of both that set him apart from his opponents. Nowhere is the severability of the two propositions more apparent than with Marshall's critics in his home state of Virginia. -

For the Good of the Few: Defending the Freedom of the Press in Post-Revolutionary Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2003 For the Good of the Few: Defending the Freedom of the Press in Post-Revolutionary Virginia Emily Terese Peterson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Peterson, Emily Terese, "For the Good of the Few: Defending the Freedom of the Press in Post- Revolutionary Virginia" (2003). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626416. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0hcz-hr19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOR THE GOOD OF THE FEW: DEFENDING THE FREEDOM OF THE PRESS IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY VIRGINIA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Emily T. Peterson May 2003 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 2003 Robert Gross ChrtstophW Grasso Dale Hoak TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION: DEFINING EARLY AMERICAN PRESS LIBERTY 2 CHAPTER I. ‘USHACKLED, UNLIMITED, AND UNDEFINED:’ PRESS LIBERTY IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGIN A, 1776-1811 22 CHAPTER II.