1 Rethinking Avaldsnes and Kormt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12-Death-And-Changing-Rituals.Pdf

This pdf of your paper in Death and Changing Rituals belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (December 2017), unless the site is a limited access intranet (password protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books (editorial@ oxbowbooks.com). Studies in Funerary Archaeology: Vol. 7 An offprint from DEATH AND CHANGING RITUALS Function and Meaning in Ancient Funerary Practices Edited by J. Rasmus Brandt, Marina Prusac and Håkon Roland Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-639-4 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-640-0 © Oxbow Books 2015 Oxford & Philadelphia www.oxbowbooks.com Published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by OXBOW BOOKS 10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford OX1 2EW and in the United States by OXBOW BOOKS 908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083 © Oxbow Books and the individual contributors 2015 Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-639-4 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-640-0 A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brandt, J. Rasmus. Death and changing rituals : function and meaning in ancient funerary practices / edited by J. Rasmus Brandt, Häkon Roland and Marina Prusac. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-78297-639-4 1. Funeral rites and ceremonies, Ancient. I. Roland, Häkon. II. Prusac, Marina. III. Title. GT3170.B73 2014 393’.93093--dc23 2014032027 All rights reserved. -

Iconic Hikes in Fjord Norway Photo: Helge Sunde Helge Photo

HIMAKÅNÅ PREIKESTOLEN LANGFOSS PHOTO: TERJE RAKKE TERJE PHOTO: DIFFERENT SPECTACULAR UNIQUE TROLLTUNGA ICONIC HIKES IN FJORD NORWAY PHOTO: HELGE SUNDE HELGE PHOTO: KJERAG TROLLPIKKEN Strandvik TROLLTUNGA Sundal Tyssedal Storebø Ænes 49 Gjerdmundshamn Odda TROLLTUNGA E39 Våge Ølve Bekkjarvik - A TOUGH CHALLENGE Tysnesøy Våge Rosendal 13 10-12 HOURS RETURN Onarheim 48 Skare 28 KILOMETERS (14 KM ONE WAY) / 1,200 METER ASCENT 49 E134 PHOTO: OUTDOORLIFENORWAY.COM PHOTO: DIFFICULTY LEVEL BLACK (EXPERT) Fitjar E134 Husnes Fjæra Trolltunga is one of the most spectacular scenic cliffs in Norway. It is situated in the high mountains, hovering 700 metres above lake Ringe- ICONIC Sunde LANGFOSS Håra dalsvatnet. The hike and the views are breathtaking. The hike is usually Rubbestadneset Åkrafjorden possible to do from mid-June until mid-September. It is a long and Leirvik demanding hike. Consider carefully whether you are in good enough shape Åkra HIKES Bremnes E39 and have the right equipment before setting out. Prepare well and be a LANGFOSS responsible and safe hiker. If you are inexperienced with challenging IN FJORD Skånevik mountain hikes, you should consider to join a guided tour to Trolltunga. Moster Hellandsbygd - A THRILLING WARNING – do not try to hike to Trolltunga in wintertime by your own. NORWAY Etne Sauda 520 WATERFALL Svandal E134 3 HOURS RETURN PHOTO: ESPEN MILLS Ølen Langevåg E39 3,5 KILOMETERS / ALTITUDE 640 METERS Vikebygd DIFFICULTY LEVEL RED (DEMANDING) 520 Sveio The sheer force of the 612-metre-high Langfossen waterfall in Vikedal Åkrafjorden is spellbinding. No wonder that the CNN has listed this 46 Suldalsosen E134 Nedre Vats Sand quintessential Norwegian waterfall as one of the ten most beautiful in the world. -

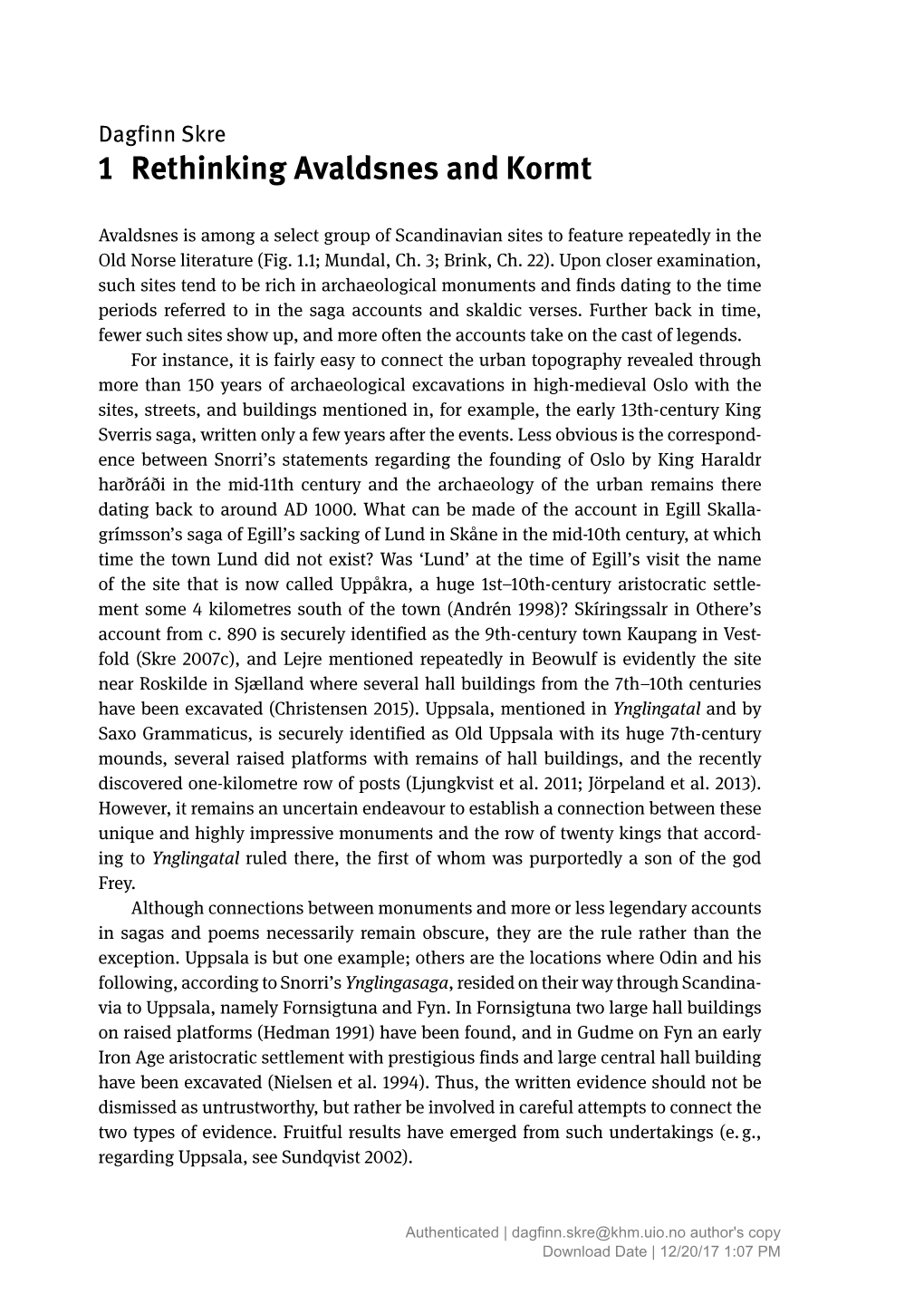

Experience Karmøy

E39 E134 Experience BUS SERVICE TO E134 VANDVIK ØRJAN B. IVERSEN, CAMILLA APPEX.NO / PHOTOS: OSLO, BERGEN, AKSDAL STAVANGER HAUGESUND DYRAFJELLET 172 M.A.S.L Karmøy FAST FERRY: N HAUGESUND - FEØY 20 MIN 9-HOLES HAUSKE GÅRD MINIGOLF 18-HOLES E134 VIKING FARM VISNES MINE AREA KVEITEVIKEN THE FIVE POOR MAIDENS E39 FV47 OLAV’S CHURCH E134 STATUE OF LIBERTY HAUGESUND AIRPORT, E134 KARMØY FV47 HÅVIK HØYEVARDE BUS SERVICE 19 KM K AR TO STAVANGER MØYTUNNELEN AND BERGEN NORDVEGEN HISTORY CENTRE FV47 16 KM Haugalands- KARMØY FISHERY MUSEUM vatnet VEAVÅGEN 12 KM FV47 KOPERVIK ÅKREHAMN COASTAL MUSEUM FV511 ÅKREHAMN 4 KM BEAUTIFUL SILKY BEACHES B SÅLEFJELL PEAK UR MA VE GE BOATHOUSES N AT HOP 8 KM E39 13 KM 8 KM 9-HOLES GREAT SURFING BEACHES FERRY: ARSVÅGEN - MORTAVIKA 20 MIN SKUDENESHAVN JUNGLE PARK STAVANGER HISTORIC SKUDENESHAVN SYRENESET FORT THE MUSEUM IN MÆLANDSGÅRDEN SKUDENESHAVN VIKEHOLMEN GEITUNGEN SIGHTSEEING HIKING AND BIKING TRAILS ACCOMMODATION COMMUNICATIONS Avaldsnes Viking Farm. Follow in the foot- The Karmøy countryside is attractive and diverse Park Inn, Haugesund Airport Hotel Airlines steps of the ancient kings through the historic with many opportunities to get outdoors and Helganesveien 24, 4262 Avaldsnes RyanAir: T: +47 52 85 78 00, www.ryanair.com landscape at Avaldsnes. Bukkøy island features be active or simply relax: T: +47 52 86 10 90 Norwegian: T: +47 815 21 815, www.norwegian.no many reconstructed Viking buildings. Meet www.haugalandet.friskifriluft.no E-mail: [email protected] SAS: T: +47 05400, www.sas.no Vikings for activities and tours in the summer www.parkinnhotell.no/hotell-haugesund Widerøe: T: +47 810 01 200, www.wideroe.no season. -

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

New Datings of Three Courtyard Sites in Rogaland

Frode Iversen 26 Emerging Kingship in the 8th Century? New Datings of three Courtyard Sites in Rogaland The Norwegian ‘courtyard sites’ have variously been interpreted as special cultic, juridical, or military assembly sites, which served at more than the purely local level. Previously, on the basis of studies of artefacts and finds of pottery from these structures, the principal period of use of the courtyard sites in Rogaland has been dated to the early and late Roman Iron Age (AD 1–400) and the Migration Period (AD 400–550) through c. AD 600. To test the validity of this date range, the Avaldsnes Royal Manor Project has commissioned thirty new radiocarbon datings of material from three courtyard sites in Rogaland that Jan Petersen had excavated in 1938–50. These are Øygarden, Leksaren, and Klauhaugane; the latter is one of the largest courtyard sites in Norway. Øygarden has not previously been radiocarbon dated. For Klauhaugene, only a few radiocarbon dates had been obtained prior to this study. Leksaren was radiocarbon dated in the 1990s, with the results rather surprisingly indicating that its use continued into the 7th century. The present study demonstrates that the three investigated sites were in use during the Merovingian Period (AD 550–800) – a finding that both confirms and develops previous chronological frameworks. The courtyard sites in Rogaland fell out of use earlier than in other areas along the western coast of Norway. It is therefore suggested that their abandonment was connected to the emergence in the 8th century of royal power accompanied by greater control over jurisdiction – a royal power that subsequently expanded within the coastal zone. -

ROGALAND 23. JULY – 4. AUGUST 2014 Sunday the 27Th We Traveled

ROGALAND 23. JULY – 4. AUGUST 2014 Sunday the 27th we traveled to Karmøy. We drove Here we have parked. through the new tunnel in the triangular connection to Skudesneshavn. We stopped at Skudenes Camping. We parked at this place. The following day, Sunday the 28th, we took a trip down to Skudesneshavn. Those who live here can park their boat right outside Here we are at Kanalen. their door. View across the strait to Vaholmen. Terraces with moored boats. View south towards the bridge that goes over to Skudenes Mekaniske Verksted was built in 1916. Here Steiningsholmen. were the Skude engines produced. I the end of the house is written the name on the wall. Here we come to the square located down by the harbor. Skudeneshavn is a town and a former municipality in Karmøy municipality in Rogaland. Skudesneshavn had 3,327 inhabitants as of 1 January 2013, and is located on Skudeneset on the southern tip of the island Karmøy. Skudesneshavn grew up in the late Middle Ages and the urban society grew rapidly during the herring fishery in the 1800s.Today, the city has modern shipbuilding industry and one of the largest offshore shipping. Solstad Offshore has one of the world's most advanced offshore fleets in service throughout the world. The well-preserved wooden buildings along the harbor, Søragadå, has become one of the region's most visited tourist destination. The flounder fisherman The lobster fisherman The statues in Nordmand valley, Denmark In Nordmandsdalen in Fredensborg Palace Gardens stand 60 statues from various parts of Norway. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Space Plants from Norway

June July, 2006 NEWSLETTER Service Dear Lodge/District Editors: We are pleased to provide the latest edition of the Newsletter Service. This complimentary service is printed six times each year and may be used as a supplement to your lodge newsletter. The Newsletter Service provides a variety of information, including current news and culture related articles. The Newsletter Service is also available on the Web at www.sonsofnorway.com, under the “Members Only” section. We hope you enjoy this issue and find its content to be beneficial. Fraternally, Eivind J. Heiberg July 2006 juli 2006 A Little in English... Litt på norsk... Olsok July 28th - 29th Olsok 28-29 juli Olsok – from the term “the wake of St. Olaf” in Olsok – fra ordet ”Olavsvaka” på norrøn – skjer Old Norse – happens primarily during the 24-hour hovedsakelig døgnet 28 til 29 juli i Norge. Olsok er period between the 28th and the 29th of July in en dag til minne om kong Olav Haraldssøn den Norway. Olsok is a day of memory for king Olav hellige, eller Sant Olav som han er bedre kjent i Haraldsson the Holy, or Saint Olav as he is better utlandet. Sant Olav krediteres med kristning av known abroad. Saint Olav is credited with Norge og han falt i slaget på Stiklestad i Trøndelag christianizing Norway, and fell in the Battle of den 29. juli i 1030. Stiklestad in Trondelag July 29th, 1030. The day is an official flag day, and in many communities, Dagen er offisiell flaggdag, og i mange bygder, especially in Western Norway, people burn særlig på Vestlandet, brenner folk bål for å markere bonfires to mark the day. -

{ }Appendix 2 to Annex

9.7.2021 - EEA AGREEMENT - ANNEX XXI – p. 58 {1} APPENDIX 2 TO ANNEX XXI {2} LIST OF EFTA PORTS {3} Please note that special aggregates are not included in the number of national ports. Nat. Statistical Special CTRY MCA UNLocode Port Name Stat. Port Aggregate Group IS IS00 ISAKR Akranes X IS IS00 ISAKU Akureyri X IS IS00 ISASS Árskógssandur X IS IS00 ISBAK Bakkafjörður X IS IS00 ISBIL Bíldudalur X {1} This heading was introduced by Decision No 152/2002 (OJ L 19, 23.1.2003, p. 39 and EEA Supplement No 4, 23.1.2003, p. 26) e.i.f. 9.11.2002. {2} This sub-heading was introduced by Decision No 152/2002 (OJ L 19, 23.1.2003, p. 39 and EEA Supplement No 4, 23.1.2003, p. 26) e.i.f. 9.11.2002. {3} Table contents was replaced by Decision No 73/2009 (OJ L 232, 3.9.2009, p. 30 and EEA Supplement No 47, 3.9.2009, p. 34), e.i.f. 30.5.2009 and subsequently replaced by Decision No 197/2019 (OJ L [to be published] and EEA Supplement No [to be published]) e.i.f. 11.7.2019 and subsequently corrected before publication by Corrigendum of 11.12.2020. 9.7.2021 - EEA AGREEMENT - ANNEX XXI – p. 59 IS IS00 ISBLO Blönduós X IS IS00 ISBOL Bolungarvík X IS IS00 ISBGJ Borgafjörður eystri X IS IS00 ISBRE Breiðdalsvík X IS IS00 ISBRJ Brjánslækur X IS IS00 ISDAL Dalvík X IS IS00 ISDJU Djúpivogur X IS IS00 ISESK Eskifjörður X IS IS00 ISFAS Fáskrúðsfjörður X IS IS00 ISFLA Flateyri X IS IS00 ISGRD Garður X IS IS00 ISGRY Grímsey X IS IS00 ISGRI Grindavík X IS IS00 ISGRF Grundarfjörður X IS IS00 ISGRT Grundartangi X IS IS00 ISHAF Hafnarfjörður X IS IS00 ISHNR Hafnir X IS IS00 ISHFN Höfn, Hornafjörður X IS IS00 ISHOF Hofsós X IS IS00 ISHVK Hólmavík X IS IS00 ISHRI Hrísey X 9.7.2021 - EEA AGREEMENT - ANNEX XXI – p. -

Kulturminner I Karmøybarnehagenes Nærmiljø

KULTURMINNER I KARMØYBARNEHAGENES NÆRMILJØ Kulturminner I Karmøybarnehagenes nærmiljø Karmøy kommune 1 I Kulturminner i Karmøybarnehagene.......................................... 3 N felles kulturminner ................................................................................ 4 N Avaldsnes barnehage .............................................................................. 8 Avaldsnes barnehage, avd. Visnes ................................................... 10 H Bygnes barnehage ..................................................................................... 12 eidsbakkane barnehage ......................................................................... 14 O Eventyrhagen barnehage .................................................................... 17 L Fladaberg barnehage .............................................................................. 19 hakkebakkeskogen barnehage .......................................................... 20 D Vormedal barnehage ............................................................................... 20 Helganes barnehage ................................................................................ 23 Karmsund barnehage .............................................................................. 24 Karmsund barnehage, avd. Fosen .................................................... 26 Kolnes barnehage ..................................................................................... 28 Århaug barnehage ................................................................................... -

Study of Heathland Succession, Prescribed Burning, and Future Perspectives at Kringsjå, Norway

land Article Study of Heathland Succession, Prescribed Burning, and Future Perspectives at Kringsjå, Norway Anna Marie Gjedrem 1,2 and Torgrim Log 1,* 1 Fire Disasters Research Group, Chemistry and Biomedical Laboratory Sciences, Department of Safety, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, 5528 Haugesund, Norway; [email protected] 2 CERIDES—Excellence in Innovation and Technology, European University Cyprus, 6 Diogenes Street, Engomi, Nicosia 1516, Cyprus * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-900-500-01 Received: 31 October 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020; Published: 2 December 2020 Abstract: The coastal heathland of Western Europe, dominated by Calluna vulgaris L., was previously maintained by prescribed-burning and grazing to the extent that the Calluna became anthropogenically adapted to regular burning cycles. This 5000–6000-year-old land management practice was essential for local biodiversity and created a vegetation free from major wildland fires. In Norway, recent neglect has, however, caused accumulation of live and dead biomass. Invasion of juniper and Sitka spruce has resulted in limited biodiversity and increasing wildland fire fuels. At the Kringsjå cabin and sheep farm, Haugesund, an area of previous fire safe heathland has been restored through fire-agriculture. Kringsjå is located close to several important Viking Age sites and the Steinsfjellet viewpoint, a popular local tourist destination. The motivation for the present study is to analyse this facility and investigate possibilities for synergies between landscape management and tourism as a route to sustainable transitions. The present study compares restored heathland vegetation with unmanaged heathland at Kringsjå. The potential for activities is also analysed based on the proximity to the tourist attractions in the region. -

Pilegrimskart for Rogaland Røldal: I Middelalderen Norges Mest Søkte Pilegrimsmål, Etter Nidaros

Pilegrimskart for Rogaland Røldal: I middelalderen Norges mest søkte pilegrimsmål, etter Nidaros. Undergjørende krusifiks. Nå arrangeres årlige pilegrimsstevner. Mål for Å legge ut på pilegrimsvandring er enkelt. Langs de pilegrimsstier som er etablert, for eksempel langs Jærkysten vandringer fra flere retninger. eller Stavanger Turistforenings hverdagstur nr. 52 i Stavanger, kan du når som helst gå alene eller sammen med familie og venner. Dessuten er enhver lokal kirke et helligsted, et pilegrimsmål. Ved å la en eller flere kirker bli turmål, kan du lage egne pilegrimsvandringer og tradisjoner. Se mer om dette på den andre siden av brosjyren. Stadig flere menigheter i Den norske kirke arrangerer kortere eller lengre pilegrimsvandringer, gjerne i nærmiljøet. Suldalsskaret Følg med i menighetsbladene, på menighetenes hjemmesider Pilegrimsvandring fra Ølensvåg Sauda til Kyrkjestaden, den gamle Bjoa kyrkjevegen i Ølen. Nesflaten Udland Saudasjøen Mokleiv. Vandringer m. m. Samarbeider med Utstein Pilegrimsgard www.mokleiv.no Skåtre Pilegrimsvandring fra Pilegrimsvandring fra Ølen Hylsskaret Bukkøy til Olavskirken på Vikebygd til Skjold. Vikebygd Sandeid Avaldsnes. Hver Olsok Skåre menighet arr. Hylen organisert vandring fra Olavsseglet Toskatjønn til Olavskirken. Vår Frelsers kirke Førre Aksdal Suldal Vikedal Imsland Gard, steinkors Skjold Udland Erord Nedstrand Erord Nedstrand Skåre Rossabø Røvær Vats Sand TorvastadVår Frelser Jelsa Jelsa Norheim Haugesund Marvik Skjolda- Rossabø Aksdal Pilegrimsreise med buss, båt og Førre straumen til