8 Avaldsnes' Position in Norway in the 14Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12-Death-And-Changing-Rituals.Pdf

This pdf of your paper in Death and Changing Rituals belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (December 2017), unless the site is a limited access intranet (password protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books (editorial@ oxbowbooks.com). Studies in Funerary Archaeology: Vol. 7 An offprint from DEATH AND CHANGING RITUALS Function and Meaning in Ancient Funerary Practices Edited by J. Rasmus Brandt, Marina Prusac and Håkon Roland Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-639-4 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-640-0 © Oxbow Books 2015 Oxford & Philadelphia www.oxbowbooks.com Published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by OXBOW BOOKS 10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford OX1 2EW and in the United States by OXBOW BOOKS 908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083 © Oxbow Books and the individual contributors 2015 Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-639-4 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-640-0 A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brandt, J. Rasmus. Death and changing rituals : function and meaning in ancient funerary practices / edited by J. Rasmus Brandt, Häkon Roland and Marina Prusac. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-78297-639-4 1. Funeral rites and ceremonies, Ancient. I. Roland, Häkon. II. Prusac, Marina. III. Title. GT3170.B73 2014 393’.93093--dc23 2014032027 All rights reserved. -

ROGALAND 23. JULY – 4. AUGUST 2014 Sunday the 27Th We Traveled

ROGALAND 23. JULY – 4. AUGUST 2014 Sunday the 27th we traveled to Karmøy. We drove Here we have parked. through the new tunnel in the triangular connection to Skudesneshavn. We stopped at Skudenes Camping. We parked at this place. The following day, Sunday the 28th, we took a trip down to Skudesneshavn. Those who live here can park their boat right outside Here we are at Kanalen. their door. View across the strait to Vaholmen. Terraces with moored boats. View south towards the bridge that goes over to Skudenes Mekaniske Verksted was built in 1916. Here Steiningsholmen. were the Skude engines produced. I the end of the house is written the name on the wall. Here we come to the square located down by the harbor. Skudeneshavn is a town and a former municipality in Karmøy municipality in Rogaland. Skudesneshavn had 3,327 inhabitants as of 1 January 2013, and is located on Skudeneset on the southern tip of the island Karmøy. Skudesneshavn grew up in the late Middle Ages and the urban society grew rapidly during the herring fishery in the 1800s.Today, the city has modern shipbuilding industry and one of the largest offshore shipping. Solstad Offshore has one of the world's most advanced offshore fleets in service throughout the world. The well-preserved wooden buildings along the harbor, Søragadå, has become one of the region's most visited tourist destination. The flounder fisherman The lobster fisherman The statues in Nordmand valley, Denmark In Nordmandsdalen in Fredensborg Palace Gardens stand 60 statues from various parts of Norway. -

Space Plants from Norway

June July, 2006 NEWSLETTER Service Dear Lodge/District Editors: We are pleased to provide the latest edition of the Newsletter Service. This complimentary service is printed six times each year and may be used as a supplement to your lodge newsletter. The Newsletter Service provides a variety of information, including current news and culture related articles. The Newsletter Service is also available on the Web at www.sonsofnorway.com, under the “Members Only” section. We hope you enjoy this issue and find its content to be beneficial. Fraternally, Eivind J. Heiberg July 2006 juli 2006 A Little in English... Litt på norsk... Olsok July 28th - 29th Olsok 28-29 juli Olsok – from the term “the wake of St. Olaf” in Olsok – fra ordet ”Olavsvaka” på norrøn – skjer Old Norse – happens primarily during the 24-hour hovedsakelig døgnet 28 til 29 juli i Norge. Olsok er period between the 28th and the 29th of July in en dag til minne om kong Olav Haraldssøn den Norway. Olsok is a day of memory for king Olav hellige, eller Sant Olav som han er bedre kjent i Haraldsson the Holy, or Saint Olav as he is better utlandet. Sant Olav krediteres med kristning av known abroad. Saint Olav is credited with Norge og han falt i slaget på Stiklestad i Trøndelag christianizing Norway, and fell in the Battle of den 29. juli i 1030. Stiklestad in Trondelag July 29th, 1030. The day is an official flag day, and in many communities, Dagen er offisiell flaggdag, og i mange bygder, especially in Western Norway, people burn særlig på Vestlandet, brenner folk bål for å markere bonfires to mark the day. -

Kulturminner I Karmøybarnehagenes Nærmiljø

KULTURMINNER I KARMØYBARNEHAGENES NÆRMILJØ Kulturminner I Karmøybarnehagenes nærmiljø Karmøy kommune 1 I Kulturminner i Karmøybarnehagene.......................................... 3 N felles kulturminner ................................................................................ 4 N Avaldsnes barnehage .............................................................................. 8 Avaldsnes barnehage, avd. Visnes ................................................... 10 H Bygnes barnehage ..................................................................................... 12 eidsbakkane barnehage ......................................................................... 14 O Eventyrhagen barnehage .................................................................... 17 L Fladaberg barnehage .............................................................................. 19 hakkebakkeskogen barnehage .......................................................... 20 D Vormedal barnehage ............................................................................... 20 Helganes barnehage ................................................................................ 23 Karmsund barnehage .............................................................................. 24 Karmsund barnehage, avd. Fosen .................................................... 26 Kolnes barnehage ..................................................................................... 28 Århaug barnehage ................................................................................... -

Study of Heathland Succession, Prescribed Burning, and Future Perspectives at Kringsjå, Norway

land Article Study of Heathland Succession, Prescribed Burning, and Future Perspectives at Kringsjå, Norway Anna Marie Gjedrem 1,2 and Torgrim Log 1,* 1 Fire Disasters Research Group, Chemistry and Biomedical Laboratory Sciences, Department of Safety, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, 5528 Haugesund, Norway; [email protected] 2 CERIDES—Excellence in Innovation and Technology, European University Cyprus, 6 Diogenes Street, Engomi, Nicosia 1516, Cyprus * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-900-500-01 Received: 31 October 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020; Published: 2 December 2020 Abstract: The coastal heathland of Western Europe, dominated by Calluna vulgaris L., was previously maintained by prescribed-burning and grazing to the extent that the Calluna became anthropogenically adapted to regular burning cycles. This 5000–6000-year-old land management practice was essential for local biodiversity and created a vegetation free from major wildland fires. In Norway, recent neglect has, however, caused accumulation of live and dead biomass. Invasion of juniper and Sitka spruce has resulted in limited biodiversity and increasing wildland fire fuels. At the Kringsjå cabin and sheep farm, Haugesund, an area of previous fire safe heathland has been restored through fire-agriculture. Kringsjå is located close to several important Viking Age sites and the Steinsfjellet viewpoint, a popular local tourist destination. The motivation for the present study is to analyse this facility and investigate possibilities for synergies between landscape management and tourism as a route to sustainable transitions. The present study compares restored heathland vegetation with unmanaged heathland at Kringsjå. The potential for activities is also analysed based on the proximity to the tourist attractions in the region. -

23 the Raised Stones

Dagfinn Skre 23 The Raised Stones The spectacular raised stone north of the St Óláfr’s Church at Avaldsnes, the so called Jomfru Marias synål (Virgin Mary’s Sewing Needle), is the most prominent preserved prehistoric mon- ument at the site. Before its height was reduced c. 1840 from approximately 8.3 metres to the present 7.2 metres, it was the tallest in Scandinavia – the others rarely surpass 5 metres. A similar stone, about 6.9 metres tall, is known to have stood on the southern side of the church until the early 19th century. A 12th–15th-century runic inscription on one of the two stones was described in 1639 but has not been identified since. The stones were mentioned by Snorri in Heimskringla, and have received copious scholarly attention from the 17th century on- wards. In this chapter, the existing evidence is reassessed, and the original number of raised stones at Avaldsnes, their sizes, and the location of the runic inscription are discussed. With the aim of arriving at a probable date and original number of stones, the monument is compared to stone settings in the same region and elsewhere in Scandinavia. It is concluded that the runic inscription was likely incised on the southern stone, which was severely damaged in 1698 and finally was taken down in the early 19th century. Probably, the two existing stones were originally corners in a triangular stone setting – a monument of the 3rd–6th centuries AD. An assumed third stone would have stood in the southeast and would probably have been removed prior to the mid-17th century, possibly around 1300 when masonry buildings were erected there. -

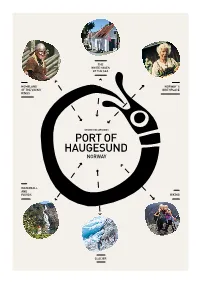

Port of Haugesund Norway

THE WHITE HAVEN BY THE SEA HOMELAND NORWAY´S OF THE VIKING BIRTHPLACE KINGS SHORE EXCURSIONS PORT OF HAUGESUND NORWAY WATERFALL AND FJORDS HIKING GLACIER CRUISE DESTINATION HAUGESUND, NORWAY CRUISE DESTINATION HAUGESUND, NORWAY NORDVEGEN HISTORY CENTRE tells the story about how Avaldsnes became The First Royal Throne of Norway. HOMELAND OF THE VIKING KINGS, FROM The Viking Farm. NORWAY´S BIRTHPLACE In Norway, and at the heart of Fjord Norway, you will find the Haugesund region. This is the Homeland of the Viking Kings – Norway’s birthplace. Here you can discover the island of Karmøy, where Avaldsnes is situated – Norway’s oldest throne. PRIOR TO the Viking Age, Avaldsnes was a seat of Avaldsnes is therefore a key point in understanding power. This is where the Vikings ruled the route the fundamental importance of voyage by sea in that gave its name to Norway – the way north. terms of Norway’s earliest history. The foundation Around 870 AD, King Harald the Fairhaired made stone of modern Norway was laid in 1814, but the Avaldsnes his main royal estate, which was country’s historical foundation is located at Avaldsnes. to become Norway’s oldest throne. Today, one can visit St. Olav’s church at Avaldsnes, From the time the first seafaring vessels were built as well as Nordvegen History Center, and the in the late Stone Age and up to the Middle Ages, Viking Farm. These are all places of importance the seat of power of the reigning princes and kings for the Vikings and the history of Norway. has been located at Avaldsnes. -

Norwegian Bergen Hosts World Cycling Championships American Story on Page 8 Volume 128, #19 • October 6, 2017 Est

the Inside this issue: NORWEGIAN Bergen hosts World Cycling Championships american story on page 8 Volume 128, #19 • October 6, 2017 Est. May 17, 1889 • Formerly Norwegian American Weekly, Western Viking & Nordisk Tidende $3 USD Who were the Vikings? As science proves that some ancient warriors assumed to be men were actually women, Ted Birkedal provides an overview of historical evidence for real-life Lagerthas WHAT’S INSIDE? « Den sanne oppdagelsesreise Nyheter / News 2-3 TERJE BIRKEDAL består ikke i å finne nye Business 4-5 Anchorage, Alaska landskaper, men å se med Opinion 6-7 In the late 19th century a high-status Viking-era were buried with a sword, an axe, a spear, arrows, and nye øyne. » Sports 8-9 grave was excavated at Birka, Sweden. The grave goods a shield. The woman from Solør was also buried with a – Marcel Proust Research & Science 10 included a sword, an axe, a spear, a battle knife, several horse with a fine bridle. Another grave from Kaupang, armor-piercing arrows, and the remains of two shields. Norway, contained a woman seated in a small boat with Norwegian Heritage 11 Two horses were also buried with the grave’s inhabitant. an axe and a shield boss. Still another high-status grave Taste of Norway 12-13 Until 2014 the grave was thought to belong to a in Rogaland, Norway, turned up a woman with a sword Norway near you 14-15 man, but a forensic study of the skeleton in 2014 sug- at her side. Many other graves throughout Scandinavia Travel 16-17 gested that the buried person was a woman. -

2 Intraregional Diversity. Approaching Changes in Political Topographies in South-Western Norway Through Burials with Brooches, AD 200–1000

Mari Arentz Østmo 2 Intraregional Diversity. Approaching Changes in Political Topographies in South-western Norway through Burials with Brooches, AD 200–1000 This chapter addresses socio-political structure and change through the examination of spatial and temporal differences in the deposition of brooches in burial contexts and aspects of burial practices. Diachronic sub-regions within Rogaland and parts of southern Hordaland are inferred, enabling a further address of the trajectories within sub-regions and how they interrelate in ongo- ing socio-political processes. The paradox of observed concurrent processes of homogenisation and upsurges of local or regional particularities is addressed through the theoretical framework of globalisation. Within the study area, the sub-regions of Jæren and the Outer coast/Karmsund appear most defined throughout the period AD 200–1000. Here, quite different trajectories are observed, indicating a parallel development of different practices and sub-regional identities. 2.1 Introduction Throughout the Iron Age, dress accessories included brooches, clasps, and pins that held garments together while simultaneously adding decorative and communi- cative elements to the dress. While the functional aspects of brooches are persis- tent, their form and ornamentation vary greatly within the first millennium AD; the typologies of brooches thus constitute a major contribution to the development of Iron Age chronology (Klæsøe 1999:89; Kristoffersen 2000:67; Lillehammer 1996; Røstad 2016a). As such, the brooches deposited in burials provide an exceptional opportunity to address both spatial and temporal variations in burial practices, and furthermore in the social groups that performed those rituals. Regionality, defined as the spatial dimension of cultural differences (Gammeltoft and Sindbæk 2008:7), is here approached on a microscale, focusing on intra-regional diversity in the selective and context-specific use of a particular part of material cul- ture, namely the brooches. -

1 Rethinking Avaldsnes and Kormt

Dagfinn Skre 1 Rethinking Avaldsnes and Kormt Avaldsnes is among a select group of Scandinavian sites to feature repeatedly in the Old Norse literature (Fig. 1.1; Mundal, Ch. 3; Brink, Ch. 22). Upon closer examination, such sites tend to be rich in archaeological monuments and finds dating to the time periods referred to in the saga accounts and skaldic verses. Further back in time, fewer such sites show up, and more often the accounts take on the cast of legends. For instance, it is fairly easy to connect the urban topography revealed through more than 150 years of archaeological excavations in high-medieval Oslo with the sites, streets, and buildings mentioned in, for example, the early 13th-century King Sverris saga, written only a few years after the events. Less obvious is the correspond- ence between Snorri’s statements regarding the founding of Oslo by King Haraldr harðráði in the mid-11th century and the archaeology of the urban remains there dating back to around AD 1000. What can be made of the account in Egill Skalla- grímsson’s saga of Egill’s sacking of Lund in Skåne in the mid-10th century, at which time the town Lund did not exist? Was ‘Lund’ at the time of Egill’s visit the name of the site that is now called Uppåkra, a huge 1st–10th-century aristocratic settle- ment some 4 kilometres south of the town (Andrén 1998)? Skíringssalr in Othere’s account from c. 890 is securely identified as the 9th-century town Kaupang in Vest- fold (Skre 2007c), and Lejre mentioned repeatedly in Beowulf is evidently the site near Roskilde in Sjælland where several hall buildings from the 7th–10th centuries have been excavated (Christensen 2015). -

114917870.Pdf

. "Order my troop to construct a barrow on a headland on the coast, after my pyre has cooled. It will loom on the horizon at Hronesness and be a reminder among my people - so that in coming times crews under sail will call it Beowulf’s’ Barrow, as they steer ships across the wide and shrouded waters." - Beowulf, 2802-2808 I. Preface Growing up as a child playing on prehistoric barrows and being told stories about long forgotten battles and mighty kings, made me realise at a young age that there was a past, present and future. However, there was one particular area in my parish that caught my attention as a child, and that was Avaldsnes. The place where Norway’s first king, Harald Fairhair, is said to have had his royal manor, but also the place where one of Norway’s largest menhirs can be found. However, out of all of these stories associated with this particular area, there was one that fascinated me the most, the long forgotten story about the Flagghaug prince. Who was this person, and why was he buried in a barrow? Those were the questions that followed me through my childhood, until I reached my youth, and the making of Nordvegen History Centre resulting in better information becoming readily available for the general public. As a result, I remember reading about how the Flagghaug prince may have served in the Roman army, and established contacts with other prince’s thorough Europe. This is the basis for me wanting to write my master’s thesis about Flagghaugen. -

Experiencekarmoy2020.Pdf

EXPERIENCE KARMØY Contents Welcome to Karmøy 4 Karmøy Guide Map 6 Avaldsnes - Norway’s birthplace 8 Skudeneshavn 26 The Great Outdoors 40 North Sea beaches 56 Activities galore 62 Festivals 70 “Yellow Pages” 80 3 Welcome to Karmøy Homeland of the Viking Kings – Norway’s Birthplace Come and experience Karmøy – with rocks and skerries protecting us from the raging sea in the West. With long, silky-smooth, sandy beaches in bays and inlets – and with eternal swells pounding the coast. Real maritime culture, dramatic ocean, silvery fresh fish and a vibrant heritage – that’s Karmøy today. With a mix of small hamlets, pleasant shopping centres, historical sights, modern industry – all jostling cheek-to-jowl with traditional agriculture and active fisheries. Walk in the footsteps of Harald Fairhair who first united Norway in a single kingdom. Olav’s Church, the Nordvegen History Centre and the Viking Farm, all at Avaldsnes, invite you to relive history. Let these chieftains and kings, with their indentured trells, be your guide. The Church and History Centre offer majestic views of sheltered Karmsund strait. 4 5 HØYEVARDE HÅVIK LIGHTHOUSE K AR BUS SERVICE MØYTUNNELEN TO STAVANGER 19KM AND BERGEN FV47 16KM Haugalands- vatnet VEAVÅGEN KARMØY FISHERY MUSEUM 12KM FV47 KOPERVIK FRISBEE ÅKREHAMN GOLF COASTAL MUSEUM FV511 ÅKREHAMN SÅLEFJELLET 132 M.A.S.L 4KM FISHERMEN´S BU RM MEMORIAL AV EG EN 8KM FRISBEE GOLF E39 13KM 8KM 9-HOLES SKUDENESHAVN JUNGLE PARK FERRY: ARSVÅGEN - MORTAVIKA (STAVANGER) 20 MIN SYRENESET FORT SKUDENESHAVN THE MUSEUM IN BEININGEN SKUDENESHAVN SKUDE LIGHTHOUSE VIKEHOLMEN LIGHTHOUSE GEITUNGEN LIGHTHOUSE Karmøy Guide Map Coastline: 140 km.