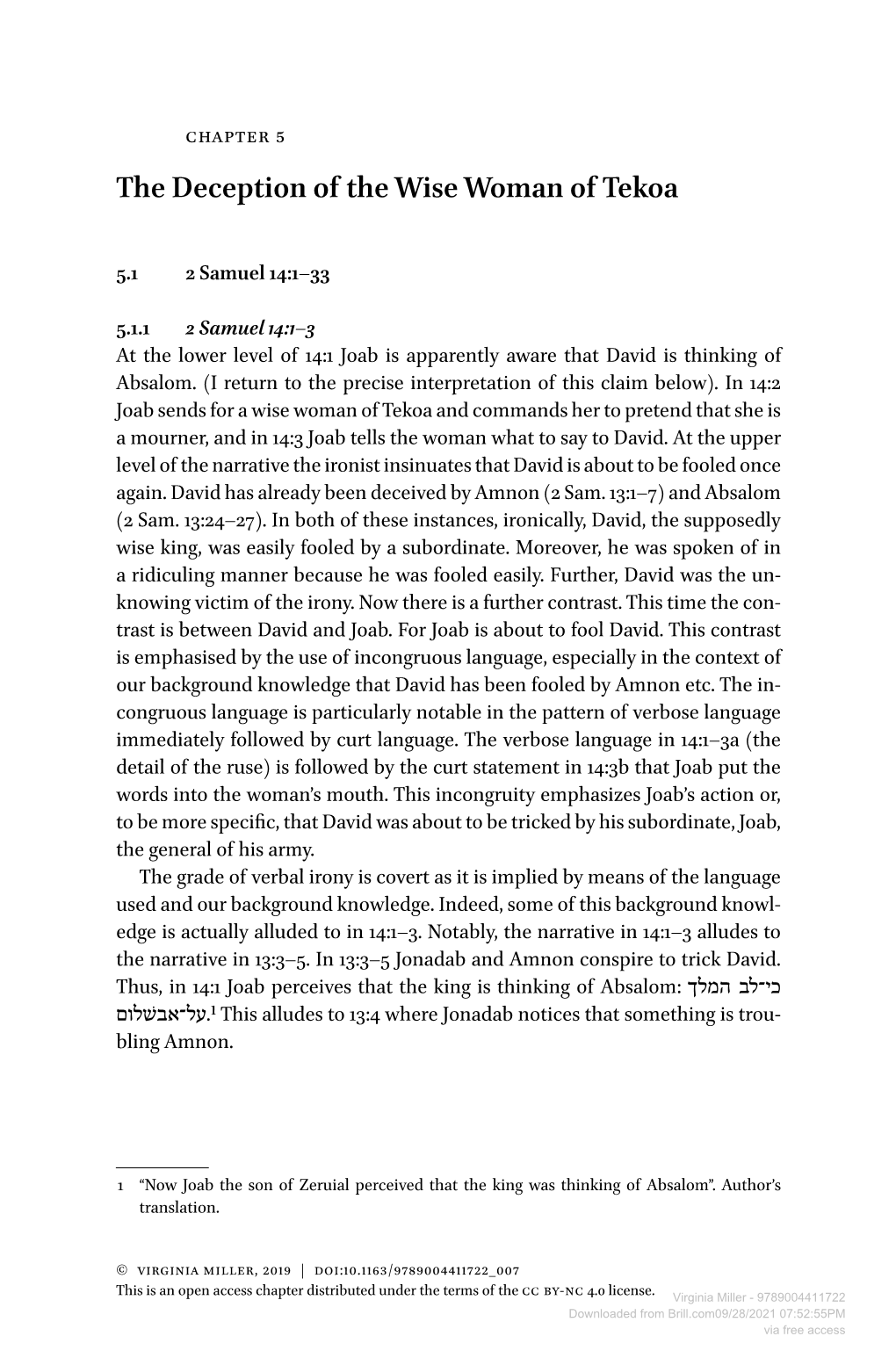

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 07:52:55PM Via Free Access 112 Chapter 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manasseh: Reflections on Tribe, Territory and Text

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Vanderbilt Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive MANASSEH: REFLECTIONS ON TRIBE, TERRITORY AND TEXT By Ellen Renee Lerner Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion August, 2014 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Douglas A. Knight Professor Jack M. Sasson Professor Annalisa Azzoni Professor Herbert Marbury Professor Tom D. Dillehay Copyright © 2014 by Ellen Renee Lerner All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people I would like to thank for their role in helping me complete this project. First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee: Professor Douglas A. Knight, Professor Jack M. Sasson, Professor Annalisa Azzoni, Professor Herbert Marbury, and Professor Tom Dillehay. It has been a true privilege to work with them and I hope to one day emulate their erudition and the kind, generous manner in which they support their students. I would especially like to thank Douglas Knight for his mentorship, encouragement and humor throughout this dissertation and my time at Vanderbilt, and Annalisa Azzoni for her incredible, fabulous kindness and for being a sounding board for so many things. I have been lucky to have had a number of smart, thoughtful colleagues in Vanderbilt’s greater Graduate Dept. of Religion but I must give an extra special thanks to Linzie Treadway and Daniel Fisher -- two people whose friendship and wit means more to me than they know. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Religious Offerings and Sacrifices in the Ancient Near East

ARAMPeriodical religious offerings and sacrifices in the ancient near east astrology in the ancient near east the river jordan volume 29, 1&2 2017 LL Aram is a peer-reviewed periodical published by the ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies The Oriental Institute University of Oxford Pusey Lane OXFORD OX1 2LE - UK Tel. +44 (0)1865 51 40 41 email: [email protected] www.aramsociety.org 6HQLRU(GLWRU'U6KD¿T$ERX]D\G8QLYHUVLW\RI2[IRUG 6KD¿TDERX]D\G#RULQVWDFXN English and French editor: Prof. Richard Dumbrill University of London [email protected] Articles for publication to be sent to ARAM at the above address. New subscriptions to be sent to ARAM at the above address. Book orders: Order from the link: www.aramsociety.org Back issues can be downloaded from: www.aramsociety.org ISSN: 0959-4213 © 2017 ARAM SOCIETY FOR SYRO-MESOPOTAMIAN STUDIES All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. iii ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies Forty-Second International Conference religious offerings and sacrifices in the ancient near east The Oriental Institute Oxford University 20-23 July 2015 iv ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies Thirty-Ninth International Conference astrology in the ancient near east The Oriental Institute Oxford University 13-15 July 2015 v ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies Forty-First International Conference the river jordan The Oriental Institute Oxford University 13-15 July 2015 vi Table of Contents Volume 29, Number I (2017) Religious Offerings in the Ancient Near East (Aram Conference 2015) Dr. -

Geshurites 140

139 Geshurites 140 Aramean Kingdom,” in Arameans, Chaldeans, and Arabs in Bab- Wieland’s Der geprüfte Abraham (1752, Abraham Justi- ylonia and Palestine in the First Millennium B.C. (ed. A. Berle- fied), and Friedrich G. Klopstock’s Der Tod Abrahams jung/M. P. Streck; Leipziger Altorientalistische Studien 3; (1753, Abraham’s Death). Formally, Gessner is partic- ■ Wiesbaden 2013) 1–29. Na aman, N., “The Kingdom of ularly influential because he uses features of bibli- Geshur in History and Memory,” SJOT 26/1 (2012) 88– 101. cal poetry as parallelism to create a prose that is Walter C. Bouzard poetic without following a strict meter (cf. Hib- berd). Gessner’s work obviously stands in the tradition Geshurites of the Christian pastoral. The action is set in a locus amoenus: in the “beautiful nature” of the “garden” 1. East of the Jordan which Adam’s family inhabits and which they con- tinually improve to make it resemble the paradise The Geshurites (MT Gĕšûrî) are the Aramaeans of they have lost. Moreover, the protagonists also act Geshur, east of the Jordan, whose boundaries are according to the conventions of the bucolic genre Gilead to the south, Mount Hermon to the north, and of the Age of Sentiment: they continually ex- and Bashan to the east (Josh 13 : 11). Though, ac- press strong feelings and passions, namely paternal cording to the book of Joshua, their land was given love, youthful rebellion, and strong compassion. to the half-tribe of Manasseh as well as to the Reub- Again and again they console each other, and even enites and the Gadites, it appears that the Israelites after the death of their son, Adam and Eve still look did not dislodge them nor the Maacathites “so that forward to the future: “The sanctifying time and Geshur and Maacath survive in the midst of Israel the victorious reason will ease our pain” (Gessner: to this day” (Josh 13 : 13). -

Baals of Bashan

RB.2014 - T. 121-4 (pp. 506-515). BAALS OF BASHAN BY Dr. Robert D. MILLER II, O.F.S. The Catholic University of America Washington, DC USA Department of Old Testament Studies University of Pretoria SOUTH AFRICA SUMMARY This essay argues that the phrase “Bulls of Bashan” is not about famous cattle but about cultic practice. Although this has been suggested before, this essay uses archaeology and climatology to show ancient Golan was no place for raising cattle. SOMMAIRE Cet essai fait valoir que l’expression « Taureaux de Basan » ne concerne pas les célèbres bovins mais des pratiques rituelles. Bien que cela ait été sug- géré auparavant, cet essai utilise archéologie et climatologie pour montrer que le Golan antique n’était pas un endroit pour l’élevage du bétail. The phrase “Bulls of Bashan” occurs twice in the Hebrew Bible (Ps 22:12; Ezek 39:18; cf. Jer 50:19), along with Amos 4:1’s mention of “Cows of Bashan.” The vast majority of commentators have under- stood this to refer to the “famous cattle” of Bashan, a region supposedly renowned for its beef or dairy production.1 I would like to challenge this 1 Thus, inter alia, Mitchell DAHOOD, Psalms AB (Garden City: Doubleday, 1979), 1.140; Klaus KOCH, TheProphets:TheAssyrianPeriod(Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983), 46; Avraham NEGEV, ed., ArchaeologicalEncyclopediaoftheHolyLand(New York: Continuum, 2005), s.v. “Bashan,” 68; Jonathan TUBB, TheCanaanites (Tulsa: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998), 91; Walter C. KAISER, HistoryofIsrael(Nashville: Broadman 997654_RevBibl_2014-4_02_Miller_059.indd7654_RevBibl_2014-4_02_Miller_059.indd 506506 222/09/142/09/14 111:301:30 BAALS OF BASHAN 507 interpretation, arguing not only that the phrase Bulls of Bashan refers not to the bovine but to the divine, but moreover that Iron Age Bashan would have been a terrible land for grazing and the last place to be famous for beef or dairy cattle. -

Joshua 13:1–33 1Now Joshua Was Old, Advanced in Years. and the LORD Said to Him: “You Are Old, Advanced in Years, and There

Joshua 13 Joshua 13:1–33 1Now Joshua was old, advanced in years. And the LORD said to him: “You are old, advanced in years, and there remains very much land yet to be possessed. 2This is the land that yet remains: all the territory of the Philistines and all that of the Geshurites, 3from Sihor, which is east of Egypt, as far as the border of Ekron northward (which is counted as Canaanite); the five lords of the Philistines—the Gazites, the Ashdodites, the Ashkelonites, the Gittites, and the Ekronites; also the Avites; 4from the south, all the land of the Canaanites, and Mearah that belongs to the Sidonians as far as Aphek, to the border of the Amorites; 5the land of the Gebalites, and all Lebanon, toward the sunrise, from Baal Gad below Mount Hermon as far as the entrance to Hamath; 6all the inhabitants of the mountains from Lebanon as far as the Brook Misrephoth, and all the Sidonians—them I will drive out from before the children of Israel; only divide it by lot to Israel as an inheritance, as I have commanded you. 7Now therefore, divide this land as an inheritance to the nine tribes and half the tribe of Manasseh.” 8With the other half-tribe the Reubenites and the Gadites received their inheritance, which Moses had given them, beyond the Jordan eastward, as Moses the servant of the LORD had given them: 9from Aroer which is on the bank of the River Arnon, and the town that is in the midst of the ravine, and all the plain of Medeba as far as Dibon; 10all 1 the cities of Sihon king of the Amorites, who reigned in Heshbon, as far as the border of the children of Ammon; 11Gilead, and the border of the Geshurites and Maachathites, all Mount Hermon, and all Bashan as far as Salcah; 12all the kingdom of Og in Bashan, who reigned in Ashtaroth and Edrei, who remained of the remnant of the giants; for Moses had defeated and cast out these. -

Queen Mothers of Judah and the Religious Trends That Develop During Their Sons' Reign

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet Honors Program Projects Honors Program 5-2021 Mothers and Sons: Queen Mothers of Judah and the Religious Trends that Develop During Their Sons' Reign Brian Bowen Olivet Nazarene University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/honr_proj Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bowen, Brian, "Mothers and Sons: Queen Mothers of Judah and the Religious Trends that Develop During Their Sons' Reign" (2021). Honors Program Projects. 120. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/honr_proj/120 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A huge special thanks to my advisor, Kevin Mellish, Ph.D. for working with me through the whole research process from the seed of an idea to the final polished draft. Without his guidance, this project would not exist. Thank you to Pam Greenlee, Sandy Harris, and the Interlibrary Loan Department for helping me to get access to resources that would not have been available to me otherwise. Thank you to Elizabeth Schurman, Ph.D., and Dan Sharda, Ph.D. for assisting with the submission process to the Honors Council for the annotated bibliography, proposal, and thesis. Also, thanks to Elizabeth Schurman, Ph.D., Eddie Ellis, Ph.D., and Larry Murphy, Ph.D. for support with the editing and polishing of my thesis. Thanks to the Olivet Nazarene University Honors Council for giving me the opportunity and means to do this research project. -

The Causes of the Division of Israel's Kingdom

Scholars Crossing SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations 7-1984 The Causes of the Division of Israel's Kingdom Wayne Brindle Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Brindle, Wayne, "The Causes of the Division of Israel's Kingdom" (1984). SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations. 76. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Causes of the Division of Israel's Kingdom Wayne A. Brinale Solomon's kingdom was undoubtedly the Golden Age of Israel. The accomplishments of Solomon and the highlights of his reign include those things which all kings and empires sought, and most did not obtain. A prominent feature of Solomon's rule was his preparation for defense. He fortified the key cities which ringed Israel's cen ter: Hazor, Megiddo, Gezer, Beth-horon, and Baalath ( 1 Kings 9:15-19). He assembled as many as 1,400 chariots and 12,000 horsemen, and maintained 4,000 stables in which to house the horses (1 Kings 10:26; 2 Chron. 9:25). And he kept a large standing army, which required enormous amounts of food and other provisions. * Solomon also had a much larger court than David's. He appointed 12 district supervisors ( 1 Kings 4) and as many as 550 supervisors of labor ( 1 Kings 9:23), who were in turn supervised by an overseer of district officers and a prime minister.2 He had 1,000 wives or concubines, and probably had a large number of children. -

A Political History of the Arameans

A POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE ARAMEANS Press SBL ARCHAEOLOGY AND BIBLICAL STUDIES Brian B. Schmidt, General Editor Editorial Board: Aaron Brody Annie Caubet Billie Jean Collins Israel Finkelstein André Lemaire Amihai Mazar Herbert Niehr Christoph Uehlinger Number 13 Press SBL A POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE ARAMEANS From Their Origins to the End of Their Polities K. Lawson Younger Jr. Press SBL Atlanta Copyright © 2016 by SBL Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and record- ing, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, SBL Press, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Younger, K. Lawson. A political history of the Arameans : from their origins to the end of their polities / K. Lawson Younger, Jr. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical literature archaeology and Biblical studies ; number 13) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58983-128-5 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-62837- 080-5 (hardcover binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-62837-084-3 (electronic format) 1. Arameans—History. 2. Arameans—Politics and government. 3. Middle East—Politics and government. I. Title. DS59.A7Y68 2015 939.4'3402—dc23 2015004298 Press Printed on acid-free paper. SBL To Alan Millard, ֲאַרִּמֹי אֵבד a pursuer of a knowledge and understanding of Press SBL Press SBL CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................... -

ABSALOM, the DISGRACED PRINCE (II Sam

ABSALOM, THE DISGRACED PRINCE (II Sam. 13-18) Absalom was the third son of King David, by one of his wives, Maacah. Quite ironically, his name means ‘father of peace’ but unfortunately, his mother’s name means ‘depression’ and she was the daughter, - the princess, - of a man called Talmai who was the king of Geshur, which lies in the northern region known today as the Golan Heights. In those days, it was quite a distance from Jerusalem, where David was living. While there is no detail given in the Bible as to how they met and married, the ancient Rabbis were very much against the union. This was because she, - Maacah, - was not a Jewess, and the law forbid such a marriage union, and they quoted from Deuteronomy, Dt. 21:10 When thou goest forth to war against thine enemies, and the LORD thy God hath delivered them into thine hands, and thou hast taken them captive, 11 And seest among the captives a beautiful woman [also Abigail (I Sam. 25:3) and Bathsheba], and hast a desire unto her, that thou wouldest have her to thy wife; 12 Then thou shalt bring her home to thine house; and she shall shave her head, and pare [‘do up’] her nails; 13 And she shall put the raiment of her captivity from off her, and shall remain in thine house, and bewail her father and her mother a full month: and after that thou shalt go in unto her, and be her husband, and she shall be thy wife. 14 And it shall be, if thou have no delight in her, then thou shalt let her go whither she will; but thou shalt not sell her at all for money, thou shalt not make merchandise of her, because thou hast humbled her. -

A Great United Monarchy?

A Great United Monarchy? Archaeological and Historical Perspectives* ISRAEL FINKELSTEIN Twelve years have passed since I first presented – to the German Insti- tute in Jerusalem – my ideas on the chronology of the Iron Age strata in the Levant and how it impacts on our understanding of the biblical narrative on the United Monarchy of ancient Israel.1 I was naïve enough then to believe that the logic of my ‘correction’ was straight- forward and clear. Twelve years and many articles and public debates later, however, the notion of Davidic conquests, Solomonic building projects, and a glamorous United Monarchy – all based on an uncritical reading of the biblical text and in contradiction of archaeological finds – is still alive in certain quarters. This paper presents my updated views on this matter, and tackles several recent claims that archaeology has now proven the historicity of the biblical account of the great kingdom of David and Solomon. The Traditional Theory The quest for the United Monarchy has been the most spectacular ven- ture of ‘classical‘ biblical archaeology. 2 The obvious place to begin the search was Jerusalem. Yet Jerusalem proved elusive: the nature of the site made it difficult to peel away the layers of later centuries and the Temple Mount has always been beyond the reach of archaeologists. The search was therefore diverted to other sites, primarily Megid- do, specifically mentioned in 1 Kings 9:15 as having been built by So- lomon. Starting over a century ago, Megiddo became the focus of the * This study was supported by the Chaim Katzman Archaeology Fund and the Jacob M. -

Bible-Lands-Travel-Guide-2019.Pdf

Contents Maps ..............................................................1 Index ..............................................................4 Quick Reference Guide for Biblical Sites and Places .................................9 Song Lyrics ....................................................45 Daily Devotions .......................................... 109 2019 Itinerary & Travelers .......................... 123 © Berkshire Institute for Christian Studies PO Box 1888 | Lenox, MA 01240 | 413-637-4673 www.berkshireinstitute.org This resource has been compiled solely for educational use in conjunction with the BICS Bible Lands Seminar, and may not be sold or distributed for any other purpose. Cover photo by Joe Hession, used by permission. Berkshire Institute for Christian Studies o 2 o Bible Lands Travel Guide Jerusalem - the Old City o 3 o Berkshire Institute for Christian Studies Index of Biblical Sites and Places Acacia Tree (Arad) .................................................................................26 Almond Tree (Tel Dan) ...........................................................................18 Arad .......................................................................................................25 Azekah (Valley of Elah) ..........................................................................36 Bedouin Tents (Arad) .............................................................................26 Bethany .................................................................................................38 Bethlehem