Baals of Bashan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manasseh: Reflections on Tribe, Territory and Text

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Vanderbilt Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive MANASSEH: REFLECTIONS ON TRIBE, TERRITORY AND TEXT By Ellen Renee Lerner Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion August, 2014 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Douglas A. Knight Professor Jack M. Sasson Professor Annalisa Azzoni Professor Herbert Marbury Professor Tom D. Dillehay Copyright © 2014 by Ellen Renee Lerner All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people I would like to thank for their role in helping me complete this project. First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee: Professor Douglas A. Knight, Professor Jack M. Sasson, Professor Annalisa Azzoni, Professor Herbert Marbury, and Professor Tom Dillehay. It has been a true privilege to work with them and I hope to one day emulate their erudition and the kind, generous manner in which they support their students. I would especially like to thank Douglas Knight for his mentorship, encouragement and humor throughout this dissertation and my time at Vanderbilt, and Annalisa Azzoni for her incredible, fabulous kindness and for being a sounding board for so many things. I have been lucky to have had a number of smart, thoughtful colleagues in Vanderbilt’s greater Graduate Dept. of Religion but I must give an extra special thanks to Linzie Treadway and Daniel Fisher -- two people whose friendship and wit means more to me than they know. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Religious Offerings and Sacrifices in the Ancient Near East

ARAMPeriodical religious offerings and sacrifices in the ancient near east astrology in the ancient near east the river jordan volume 29, 1&2 2017 LL Aram is a peer-reviewed periodical published by the ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies The Oriental Institute University of Oxford Pusey Lane OXFORD OX1 2LE - UK Tel. +44 (0)1865 51 40 41 email: [email protected] www.aramsociety.org 6HQLRU(GLWRU'U6KD¿T$ERX]D\G8QLYHUVLW\RI2[IRUG 6KD¿TDERX]D\G#RULQVWDFXN English and French editor: Prof. Richard Dumbrill University of London [email protected] Articles for publication to be sent to ARAM at the above address. New subscriptions to be sent to ARAM at the above address. Book orders: Order from the link: www.aramsociety.org Back issues can be downloaded from: www.aramsociety.org ISSN: 0959-4213 © 2017 ARAM SOCIETY FOR SYRO-MESOPOTAMIAN STUDIES All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. iii ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies Forty-Second International Conference religious offerings and sacrifices in the ancient near east The Oriental Institute Oxford University 20-23 July 2015 iv ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies Thirty-Ninth International Conference astrology in the ancient near east The Oriental Institute Oxford University 13-15 July 2015 v ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies Forty-First International Conference the river jordan The Oriental Institute Oxford University 13-15 July 2015 vi Table of Contents Volume 29, Number I (2017) Religious Offerings in the Ancient Near East (Aram Conference 2015) Dr. -

Good News & Information Sites

Written Testimony of Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) National President Morton A. Klein1 Hearing on: A NEW HORIZON IN U.S.-ISRAEL RELATIONS: FROM AN AMERICAN EMBASSY IN JERUSALEM TO POTENTIAL RECOGNITION OF ISRAELI SOVEREIGNTY OVER THE GOLAN HEIGHTS Before the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Subcommittee on National Security Tuesday July 17, 2018, 10:00 a.m. Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2154 Chairman Ron DeSantis (R-FL) Ranking Member Stephen Lynch (D-MA) Introduction & Summary Chairman DeSantis, Vice Chairman Russell, Ranking Member Lynch, and Members of the Committee: Thank you for holding this hearing to discuss the potential for American recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, in furtherance of U.S. national security interests. Israeli sovereignty over the western two-thirds of the Golan Heights is a key bulwark against radical regimes and affiliates that threaten the security and stability of the United States, Israel, the entire Middle East region, and beyond. The Golan Heights consists of strategically-located high ground, that provides Israel with an irreplaceable ability to monitor and take counter-measures against growing threats at and near the Syrian-Israel border. These growing threats include the extremely dangerous hegemonic expansion of the Iranian-Syrian-North Korean axis; and the presence in Syria, close to the Israeli border, of: Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Quds forces; thousands of Iranian-armed Hezbollah fighters; Palestinian Islamic Jihad (another Iranian proxy); Syrian forces; and radical Sunni Islamist groups including the al Nusra Levantine Conquest Front (an incarnation of al Qaeda) and ISIS. The Iranian regime is attempting to build an 800-mile land bridge to the Mediterranean, running through Iraq and Syria. -

AMOS 44 Prophet of Social Justice

AMOS 44 Prophet of Social Justice Introduction. With Amos, we are introduced to the proclamation of Amos’ judgment, but rather in the first of the “writings prophets.” They did not only social evils that demand such judgment. preach but also wrote down their sermons. Preaching prophets like Elijah and Elisha did not write down Style. Amos’ preaching style is blunt, confrontational their sermons. In some books of the Bible, Amos and and insulting. He calls the rich ladies at the local his contemporaries (Hosea, Isaiah, etc.), are country club in Samaria “cows of Basham” (4:1). sometimes called the “Latter Prophets” to distinguish With an agricultural background, he uses symbols he them from the “Former Prophets” (Joshua, Samuel, has experienced on the land: laden wagons, roaring Nathan, etc.). lions, flocks plundered by wild beasts. Historical Context. One of the problems we DIVISION OF CHAPTERS encounter when dealing with the so-called “Latter Prophets” is the lack of historical context for their PART ONE is a collection of oracles against ministry. Since little or nothing is written in the surrounding pagan nations. These oracles imply that historical books about any of the prophets, with the God’s moral law applies not only to his chosen ones exception of Isaiah, scholars have depended on the but to all nations. In this series of condemnations, text of each prophetic book to ascertain the historical Judah and Israel are not excluded (chs 1-2). background of each of the prophets. Some of the books provide very little historical information while PART TWO is a collection of words and woes against others give no clues at all. -

If Not Empire, What? a Survey of the Bible

If Not Empire, What? A Survey of the Bible Berry Friesen John K. Stoner www.bible-and-empire.net CreateSpace December 2014 2 If Not Empire, What? A Survey of the Bible If Not Empire, What? A Survey of the Bible Copyright © 2014 by Berry Friesen and John K. Stoner The content of this book may be reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ International Standard Book Number: 978-0692344781 For Library of Congress information, contact the authors. Bible quotations unless otherwise noted are taken from the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Cover design by Judith Rempel Smucker. For information or to correspond with the authors, send email to [email protected] Bound or electronic copies of this book may be obtained from www.amazon.com. The entire content also is available in PDF format reader at www.bible-and-empire.net. For the sake of concordance with our PDF edition, the page numbering in this book begins with the title page. Published in cooperation with CreateSpace, DBA On-Demand Publishing, LLC December 2014 If Not Empire, What? A Survey of the Bible 3 *** Naboth owned a vineyard beside the palace grounds; the king asked to buy it. Naboth refused, saying, “This land is my ancestral inheritance; YHWH would not want me to sell my heritage.” This angered the king. Not only had Naboth refused to sell, he had invoked his god as his reason. -

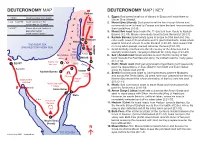

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

Intertestamental Al Survey

INTERTESTAMENTAL AL SURVEY INTRODUCTION The 400 “Silent Years” between the Old and New Testaments were anything but “silent.” I. Intertestamental sources A. Jewish 1. Historical books of Apocrypha/Pseudepigrapha a. I Maccabees b. Legendary accounts: II & III Maccabees, Letter of Aristaeus 2. DSS from the I century B.C. a. “Manual of Discipline” b. “Damascus Document” 3. Elephantine papyri (ca. 494-400 B.C.; esp. 407) a. Mainly business correspondence with many common biblical Jewish names: Hosea, Azariah, Zephaniah, Jonathan, Zechariah, Nathan, etc. b. From a Jewish colony/fortress on the first cataract of the Nile (1)Derive either from Northern exiles used by Ashurbanipal vs. Egypt (2)Or from Jewish mercenaries serving Persian Cambyses c. The 407 correspondence significantly is addressed to Bigvai, governor of Judah, with a cc: to the sons of Sanballat, governor of Samaria. The Jews of Elephantine ask for aid in rebuilding their “temple to Yaho” that had been destroyed at the instigation of the Egyptian priests 4. Philo Judaeus (ca. 20 B.C.-40 A.D.) a. Neo-platonist who used allegory to synthesize Jewish and Greek thought b. His nephew, (Tiberius Julius Alexander), served as procurator of Judea (46-48) and as prefect of Egypt (66-70) INTERTESTAMENT - History - p. 1 5. Josephus (?) (ca. 37-100 a.d.) 73 a.d. a. History of the Jewish Wars (ca 168 b.c. – 70 a.d.) 93 a.d. b. Antiquities of the Jews: apparent access to the official biography of Herod the Great as well as Roman records B. Non-Jewish 1. Greek a. -

Unorthodox Jewish Beliefs Rabbi Steven Morgen, Congregation Beth Yeshurun

Unorthodox Jewish Beliefs Rabbi Steven Morgen, Congregation Beth Yeshurun SESSION THREE: WHO WROTE THE BIBLE? 1. Traditional view: Moses as “God’s Secretary” 2. The problems with Divine/Mosaic authorship: a. Genesis Chapter 1: Not good science! (Also have all the other miracles of the Bible: 10 Plagues, Parting the Sea, Sun stands still for Joshua, etc.) b. Anachronisms: “The Canaanites were then in the land,” “King Og’s Bed,” Moses saw “Dan,” Moses wrote “Moses died”? c. Contradictions and Parallel stories: Genesis Chapter 2 – contradicts Chapter 1! AND The Brothers Try to Kill Joseph – but who saves him?? d. Moses always referred to in 3rd person e. History of Language and Literature (Homer: The Iliad and The Odyssey – written down sometime between 8th and 6th century BCE – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homer ) 3. The “Un-Orthodox” view: Modern Biblical criticism a. First, a little history: Important Dates in Biblical History b. Documentary Hypothesis: J-E-P-D (See Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible?) c. But if that is the case, what is the Torah’s authority? - 1 - DID MOSES WRITE THE ENTIRE TORAH? Subject Verses I. Anachronisms “Until today” Gen. 19:37,38/ 26:33/ Deut. 3:14/ 10:8/ 34:6 “the Canaanites were then in the Land” Gen. 12:6 (see Ibn Ezra)/ 13:7 “the land of the Hebrews” Gen. 40:15 King Og’s bed is still in “Rabba” Deut. 3:11 Who lived where, when? Deut. 2:10-12 Moses saw “Dan” ?? Deut. 34:1 (but wasn’t “Dan” until Judges 18:27-9!) Moses wrote “Moses died”? Deut. -

Geshurites 140

139 Geshurites 140 Aramean Kingdom,” in Arameans, Chaldeans, and Arabs in Bab- Wieland’s Der geprüfte Abraham (1752, Abraham Justi- ylonia and Palestine in the First Millennium B.C. (ed. A. Berle- fied), and Friedrich G. Klopstock’s Der Tod Abrahams jung/M. P. Streck; Leipziger Altorientalistische Studien 3; (1753, Abraham’s Death). Formally, Gessner is partic- ■ Wiesbaden 2013) 1–29. Na aman, N., “The Kingdom of ularly influential because he uses features of bibli- Geshur in History and Memory,” SJOT 26/1 (2012) 88– 101. cal poetry as parallelism to create a prose that is Walter C. Bouzard poetic without following a strict meter (cf. Hib- berd). Gessner’s work obviously stands in the tradition Geshurites of the Christian pastoral. The action is set in a locus amoenus: in the “beautiful nature” of the “garden” 1. East of the Jordan which Adam’s family inhabits and which they con- tinually improve to make it resemble the paradise The Geshurites (MT Gĕšûrî) are the Aramaeans of they have lost. Moreover, the protagonists also act Geshur, east of the Jordan, whose boundaries are according to the conventions of the bucolic genre Gilead to the south, Mount Hermon to the north, and of the Age of Sentiment: they continually ex- and Bashan to the east (Josh 13 : 11). Though, ac- press strong feelings and passions, namely paternal cording to the book of Joshua, their land was given love, youthful rebellion, and strong compassion. to the half-tribe of Manasseh as well as to the Reub- Again and again they console each other, and even enites and the Gadites, it appears that the Israelites after the death of their son, Adam and Eve still look did not dislodge them nor the Maacathites “so that forward to the future: “The sanctifying time and Geshur and Maacath survive in the midst of Israel the victorious reason will ease our pain” (Gessner: to this day” (Josh 13 : 13). -

A Lament for Tyre and the King of Tyre

A Lamentation for Tyre and the King of Tyre Lesson 11: Ezekiel 27-28 November 10, 2019 Ezekiel Outline • 1-33 The wrath of the Lord GOD • 1-24 Oracles of wrath against Israel • 1-3 Revelation of God and • 25-32 Oracles of wrath against the commission of Ezekiel nations • 4-23 Messages of wrath for Jerusalem • 24-33 Messages of wrath during the • 33-48 Oracles of consolation for siege of Jerusalem Israel • 34-48 The holiness of the Lord GOD • 33-37 Regathering of Israel to the land • 34-39 The Restoration of Israel • 38-39 Removal of Israel’s enemies • 40-48 The restoration of the presence from the land of the Lord GOD in Jerusalem • 40-46 Reinstatement of true worship • 47-48 Redistribution of the land Then they will know that I am the LORD 4.5 • Distribution 4 • Significance 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 0.5 1.5 2.5 3.5 4.5 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11Israel 12 13 14 15 16 17 20 22 23 24 25 26 28 29 30 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 Israel Then they will know that IamtheLORD willknowthat Then they Israel Israel Israel Israel women of Israel Israel Israel Israel Israel nations Israel Israel Israel Israel Ammon Moab Philistia Tyre Israel Sidon Israel Egypt Egypt nations Egypt Israel Israel Edom Israel nations Israel nations nations Israel nations Gog judgment restoration Chapter 27 Outline • 1-11 Tyre’s former state • 12-25 Tyre’s customers • 26-36 Tyre’s fall Tyre’s former state • A lament for Tyre Ezekiel 27:1-5 • What God says versus what Tyre 1Moreover, the word of the LORD came says to me saying, 2“And you, son of man, take up a lamentation over Tyre; 3and say to Tyre, who dwells at the entrance • Perfect in beauty to the sea, merchant of the peoples to many coastlands, ‘Thus says the Lord GOD, “O Tyre, you have said, ‘I am perfect in beauty.’ 4“Your borders are in the heart of the seas; Your builders have perfected your beauty. -

Pentwater Bible Church

Pentwater Bible Church Book of Ezekiel Message 56 October 2, 2016 Ancient Tyre Arst Unknown Daniel E. Woodhead Daniel E. Woodhead – Pastor Teacher Pentwater Bible Church The Book of Ezekiel Message Fifty-Six THE LORD JUDGES TYRE PART II October 2, 2016 Daniel E. Woodhead Ezekiel 26:19- 27:11 19For thus saith the Lord Jehovah: When I shall make thee a desolate city, like the cities that are not inhabited; when I shall bring up the deep upon thee, and the great waters shall cover thee; 20then will I bring thee down with them that descend into the pit, to the people of old time, and will make thee to dwell in the nether parts of the earth, in the places that are desolate of old, with them that go down to the pit, that thou be not inhabited; and I will set glory in the land of the living: 21I will make thee a terror, and thou shalt no more have any being; though thou be sought for, yet shalt thou never be found again, saith the Lord Jehovah. 1 The word of Jehovah came again unto me, saying, 2And thou, son of man, take up a lamentation over Tyre; 3and say unto Tyre, O thou that dwellest at the entry of the sea, that art the merchant of the peoples unto many isles, thus saith the Lord Jehovah: Thou, O Tyre, hast said, I am perfect in beauty. 4Thy borders are in the heart of the seas; thy builders have perfected thy beauty. 5They have made all thy planks of fir-trees from Senir; they have taken a cedar from Lebanon to make a mast for thee.