Vegetarian Diets EMILY R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Food Pyramid and the Environmental Pyramid Andrea Poli Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition

Roma, 5 novembre 2010 The Food Pyramid and the Environmental Pyramid Andrea Poli Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition We are aware that correct nutrition is essential to health. Development and modernization have made available to an increasing number of people a varied and abundant supply of foods. Our genes, however, maintains the “efficient” attitude (thrifty genotype) selected by evolution. Without a proper cultural foundation or clear nutritional guidelines that can be applied and easily followed on a daily basis, individual, especially in the West, risk following unbalanced –if not actually incorrect- eating habits. 2 Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition The rapid increase of obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer are now the biggest problem for public health in our society, and it also has enormous socio-economic impact Health spending in the USA 5000 4.400 miliardi di Dollari The longer life 4000 expectancy 3000 increases the 2.500 miliardi possibility that risk 2000 di Dollari factors became pathologies 1000 0 1980 1990 2010 2018 3 Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition First: investment in prevention The health spending does not guarantee a healthy life expectancy (in the absence of chronic degenerative diseases) It is estimated that 1€ of investment in prevention could save 3€ for less expenditure on disease treatment (estimated forecast) 4 Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition NUTRITION and LIFESTYLE are the two factors that can have more influence not only on longevity, but also on quality of life. 5 Barilla Center -

(1)In Bold Text, Knowledge and Skill Statement

Health Course: Health - Second Grade Designated Six Weeks: Third Grading Period Unit: Our Environment/Safety/Prevention/Drugs/Alcohol Days to teach: Adjust Days To Campus Master Schedule TEKS Guiding Assessment Vocabulary Instructional Resources/ Questions/ Strategies Weblinks Specificity Our Environment HE.2.5B Describe strategies What are the Participation in Healthy Community Teacher-Led McGraw Hill: Health & for protecting the characteristics of a healthy discussion stemming Recycling Discussions Wellness 2006 environment and the environment? from guided questions. Water disposal relationship between (Examples: Wearing Emergency the environment and earbuds – noise Air Pollution Coordinated Approach individual health, pollution; minimizing Water Pollution To Child Health such as air pollution, What do you do in your hearing loss; Using Noise Pollution (Refer to Google Drive) water pollution, noise home to keep your food sunscreen to protect pollution, land safe? your skin from UV rays) pollution and ultraviolet rays. HE.2.1D What are some healthy Make a T-chart of Healthy Food Choices Generate discussion MyHealthyplate.org Identify healthy and and unhealthy food healthy and unhealthy Unhealthy Food based on T-chart unhealthy food choices? food choices Choices choices, such as a healthy breakfast, snacks and fast food choices. HE.2.1G Participation in Describe how a Teacher-Led healthy diet can help Discussion. protect the body against some diseases. Revised Winter 2016 Health Course: Health - Second Grade Designated Six Weeks: Third -

Eating a Low-Fiber Diet

Page 1 of 2 Eating a Low-fiber Diet What is fiber? Sample Menu Fiber is the part of food that the body cannot digest. Breakfast: It helps form stools (bowel movements). 1 scrambled egg 1 slice white toast with 1 teaspoon margarine If you eat less fiber, you may: ½ cup Cream of Wheat with sugar • Reduce belly pain, diarrhea (loose, watery stools) ½ cup milk and other digestive problems ½ cup pulp-free orange juice • Have fewer and smaller stools Snack: • Decrease inflammation (pain, redness and ½ cup canned fruit cocktail (in juice) swelling) in the GI (gastro-intestinal) tract 6 saltine crackers • Promote healing in the GI tract. Lunch: For a list of foods allowed in a low-fiber diet, see the Tuna sandwich on white bread back of this page. 1 cup cream of chicken soup ½ cup canned peaches (in light syrup) Why might I need a low-fiber diet? 1 cup lemonade You may need a low-fiber diet if you have: Snack: ½ cup cottage cheese • Inflamed bowels 1 medium apple, sliced and peeled • Crohn’s disease • Diverticular disease Dinner: 3 ounces well-cooked chicken breast • Ulcerative colitis 1 cup white rice • Radiation therapy to the belly area ½ cup cooked canned carrots • Chemotherapy 1 white dinner roll with 1 teaspoon margarine 1 slice angel food cake • An upcoming colonoscopy 1 cup herbal tea • Surgery on your intestines or in the belly area. For informational purposes only. Not to replace the advice of your health care provider. Copyright © 2007 Fairview Health Services. All rights reserved. Clinically reviewed by Shyamala Ganesh, Manager Clinical Nutrition. -

Vegetarian Starter Guide

do good • fEEL GREAt • LOOK GORGEOUS FREE The VegetarianSTARTER GUIDE YUM! QUICK, EASY, FUN RECIPES +30 MOUTHWATERING MEATLESS MEALS EASy • affordABLE • inspirED FOOD Welcome If you’re reading this, you’ve already taken your first step toward a better you and a better world. Think that sounds huge? It is. Cutting out chicken, fish, eggs and other animal products saves countless animals and is the best way to protect the environment. Plus, you’ll never feel more fit or look more fabulous. From Hollywood A-listers like Kristen Bell and Ellen, to musicians like Ariana Grande and Pink, to the neighbors on your block, plant-based eating is everywhere. Even former president Bill Clinton and rapper Jay-Z are doing it! Millions of people have ditched chicken, fish, eggs and other animal products entirely, and tens of millions more are cutting back. You’re already against cruelty to animals. You already want to eat healthy so you can have more energy, live longer, and lower your risk of chronic disease. Congratulations for shaping up your plate to put your values into action! And here’s the best part: it’s never been easier. With this guide at your fingertips, you’re on your way to a fresher, happier you. And this is just the start. You’ll find more recipes, tips, and personal support online at TheGreenPlate.com. Let’s get started! Your Friends at Mercy For Animals reinvent revitalize rewrite rediscover your routine. With the your body. Healthy, plant- perfection. This isn’t about flavor. Prepare yourself easy tips in this guide, based food can nourish being perfect. -

Using Fast Food Nutrition Facts to Make Healthier Menu Selections

Teaching Idea Using Fast Food Nutrition Facts to Make Healthier Menu Selections Jennifer Turley ABSTRACT Objectives: This teaching idea enables students to (1) access and analyze fast food nutrition facts information (Calorie, total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sugar, and sodium content); (2) decipher unhealthy and healthier food choices from fast food restaurant menus for better meal and diet planning to reduce obesity and minimize disease risk; and (3) discuss consumer tips, challenges, perceptions, and needs regarding fast foods. Target Audience: Junior high, high school, or college students, with appropriate levels of difficulty included in this paper. Turley J. Using fast food nutrition facts to make healthier menu selections. Am J Health Educ. 2009;40(6):355-363. INTRODUCTION overarching goals of the Dietary Guidelines Association recently advised families to Obesity is a national and worldwide for Americans 2005, which are also echoed limit the consumption of meals outside the concern.1,2 In the United States, childhood, in the MyPyramid food guidance system, home.5 Nearly all health experts, public and adolescent, and adult obesity has steadily along with the 2006 dietary recommenda- private, agree that overweight and obesity increased. In 2007, about two-thirds (67%) tions from the American Heart Association happens when a person is in positive energy of all Americans were either overweight or and the American Cancer Society.3, 6-9 balance from chronically and consistently obese.3 Further, more children are currently Most fast food restaurants publish the consuming more Calories than they expend. in higher overweight percentile rankings, nutrition facts information on their website. -

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet a Family Resource from the Celiac Disease Program

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet A family resource from the Celiac Disease Program celiacdisease.stanfordchildrens.org What Is a Gluten-Free How Do I Diet? Get Started? A gluten-free diet is a diet that completely Your first instinct may be to stop at the excludes the protein gluten. Gluten is grocery store on your way home from made up of gliadin and glutelin which is the doctor’s office and search for all the found in grains including wheat, barley, gluten-free products you can find. While and rye. Gluten is found in any food or this initial fear may feel a bit overwhelming product made from these grains. These but the good news is you most likely gluten-containing grains are also frequently already have some gluten-free foods in used as fillers and flavoring agents and your pantry. are added to many processed foods, so it is critical to read the ingredient list on all food labels. Manufacturers often Use this guide to select appropriate meals change the ingredients in processed and snacks. Prepare your own gluten-free foods, so be sure to check the ingredient foods and stock your pantry. Many of your list every time you purchase a product. favorite brands may already be gluten-free. The FDA announced on August 2, 2013, that if a product bears the label “gluten-free,” the food must contain less than 20 ppm gluten, as well as meet other criteria. *The rule also applies to products labeled “no gluten,” “free of gluten,” and “without gluten.” The labeling of food products as “gluten- free” is a voluntary action for manufacturers. -

Foods with an International Flavor a 4-H Food-Nutrition Project Member Guide

Foods with an International Flavor A 4-H Food-Nutrition Project Member Guide How much do you Contents know about the 2 Mexico DATE. lands that have 4 Queso (Cheese Dip) 4 Guacamole (Avocado Dip) given us so 4 ChampurradoOF (Mexican Hot Chocolate) many of our 5 Carne Molida (Beef Filling for Tacos) 5 Tortillas favorite foods 5 Frijoles Refritos (Refried Beans) and customs? 6 Tamale loaf On the following 6 Share a Custom pages you’ll be OUT8 Germany taking a fascinating 10 Warme Kopsalat (Wilted Lettuce Salad) 10 Sauerbraten (German Pot Roast) tour of four coun-IS 11 Kartoffelklösse (Potato Dumplings) tries—Mexico, Germany, 11 Apfeltorte (Apple net) Italy, and Japan—and 12 Share a Custom 12 Pfefferneusse (Pepper Nut Cookies) Scandinavia, sampling their 12 Lebkuchen (Christmas Honey Cookies) foods and sharing their 13 Berliner Kränze (Berlin Wreaths) traditions. 14 Scandinavia With the helpinformation: of neigh- 16 Smorrebrod (Danish Open-faced bors, friends, and relatives of different nationalities, you Sandwiches) 17 Fisk Med Citronsauce (Fish with Lemon can bring each of these lands right into your meeting Sauce) room. Even if people from a specific country are not avail- 18 Share a Custom able, you can learn a great deal from foreign restaurants, 19 Appelsinfromage (Orange Sponge Pudding) books, magazines, newspapers, radio, television, Internet, 19 Brunede Kartofler (Brown Potatoes) travel folders, and films or slides from airlines or your local 19 Rodkal (Pickled Red Cabbage) schools. Authentic music andcurrent decorations are often easy 19 Gronnebonner i Selleri Salat (Green Bean to come by, if youPUBLICATION ask around. Many supermarkets carry a and Celery Salad) wide choice of foreign foods. -

Diet Therapy and Phenylketonuria 395

61370_CH25_369_376.qxd 4/14/09 10:45 AM Page 376 376 PART IV DIET THERAPY AND CHILDHOOD DISEASES Mistkovitz, P., & Betancourt, M. (2005). The Doctor’s Seraphin, P. (2002). Mortality in patients with celiac dis- Guide to Gastrointestinal Health Preventing and ease. Nutrition Reviews, 60: 116–118. Treating Acid Reflux, Ulcers, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Shils, M. E., & Shike, M. (Eds.). (2006). Modern Nutrition Diverticulitis, Celiac Disease, Colon Cancer, Pancrea- in Health and Disease (10th ed.). Philadelphia: titis, Cirrhosis, Hernias and More. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. Nevin-Folino, N. L. (Ed.). (2003). Pediatric Manual of Clin- Stepniak, D. (2006). Enzymatic gluten detoxification: ical Dietetics. Chicago: American Dietetic Association. The proof of the pudding is in the eating. Trends in Niewinski, M. M. (2008). Advances in celiac disease and Biotechnology, 24: 433–434. gluten-free diet. Journal of American Dietetic Storsrud, S. (2003). Beneficial effects of oats in the Association, 108: 661–672. gluten-free diet of adults with special reference to nu- Paasche, C. L., Gorrill, L., & Stroon, B. (2004). Children trient status, symptoms and subjective experiences. with Special Needs in Early Childhood Settings: British Journal of Nutrition, 90: 101–107. Identification, Intervention, Inclusion. Clifton Park: Sverker, A. (2005). ‘Controlled by food’: Lived experiences NY: Thomson/Delmar. of celiac disease. Journal of Human Nutrition and Patrias, K., Willard, C. C., & Hamilton, F. A. (2004). Celiac Dietetics, 18: 171–180. Disease January 1986 to March 2004, 2382 citations. Sverker, A. (2007). Sharing life with a gluten-intolerant Bethesda, MD: United States National Library of person: The perspective of close relatives. -

The Mayo Prescription for Good Nutrition

A PUBLICATION OF THE WELLNESS COUNCIL OF AMERICA EATING WELL: THE MAYO PRESCRIPTION FOR GOOD NUTRITION AN EXPERT INTERVIEW WITH DR. DONALD HENSRUD WELCOA.ORG EXPERT INTERVIEW EATING WELL: THE MAYO PRESCRIPTION FOR GOOD NUTRITION with DR. DONALD HENSRUD ABOUT DONALD HENSRUD, MD , MPH Dr. Hensrud is an associate professor of preventive medicine and nutrition in Mayo’s Graduate School of Medicine and the medical director for the Mayo Clinic Healthy Living Program. A specialist in nutrition and weight management, Dr. Hensrud served as editor in chief for the best-selling book The Mayo Clinic Diet and helped publish two award- winning Mayo Clinic cookbooks. ABOUT RYAN PICARELLA, MS , SPHR As President of WELCOA, Ryan works with communities and organizations around the country to ignite social movements that will improve the lives of all working people in America and around the world. With a deep interest in culture and sociology, Ryan approaches initiatives from a holistic perspective that recognizes the many paths to well- being that must be in alignment for long-term healthy lifestyle behavior change. Ryan brings immense knowledge and insight to WELCOA from his background in psychology and a career that spans human resources, organizational development and wellness program and product design. Prior to joining WELCOA, Ryan managed the award winning BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee (BCBST) Well@Work employee wellness program, a 2012 C. Everett Koop honorable mention awardee. Since relocating to Nebraska, Ryan has enjoyed an active role in the community, currently serving on the Board for the Gretchen Swanson Center for Nutrition in Omaha. Ryan has a Master of Science in Industrial and Organizational Psychology from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and a Bachelor of Science in Psychology from Northern Arizona University. -

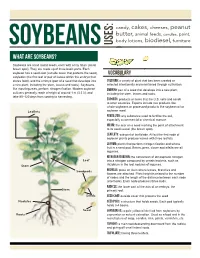

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

Revista Española De Nutrición Humana Y Dietética Spanish Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics

Rev Esp Nutr Hum Diet. 2020; 24(1). doi: 10.14306/renhyd.24.1.953 [ahead of print] Freely available online - OPEN ACCESS Revista Española de Nutrición Humana y Dietética Spanish Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics INVESTIGACIÓN versión post-print Esta es la versión aceptada. El artículo puede recibir modificaciones de estilo y de formato. Vegetarian dietary guidelines: a comparative dietetic and communicational analysis of eleven international pictorial representations Guías alimentarias vegetarianas: análisis comparativo dietético y comunicacional de once representaciones gráficas internacionales Chiara Gai Costantinoa*, Luís Fernando Morales Moranteb. a CEU Escuela Internacional de Doctorado, Universitat Abat Oliba CEU. Barcelona, Spain. b Departamento de Publicidad, Relaciones Públicas y Comunicación Audiovisual, Facultad de Ciencias de la Comunicación, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Cerdanyola del Vallès, Spain. * [email protected] Received: 14/10/2019; Accepted: 08/03/2020; Published: 30/03/2020 CITA: Gai Costantino C, Luís Fernando Morales Morante LF. Vegetarian dietary guidelines: a comparative dietetic and communicational analysis of eleven international pictorial representations. Rev Esp Nutr Hum Diet. 2020; 24(1). doi: 10.14306/renhyd.24.1.953 [ahead of print] La Revista Española de Nutrición Humana y Dietética se esfuerza por mantener a un sistema de publicación continua, de modo que los artículos se publican antes de su formato final (antes de que el número al que pertenecen se haya cerrado y/o publicado). De este modo, intentamos p oner los artículos a disposición de los lectores/usuarios lo antes posible. The Spanish Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics strives to maintain a continuous publication system, so that the articles are published before its final format (before the number to which they belong is closed and/or published). -

Nutrition Lesson 5: Eating Right to Support Your Muscles and Skin Lesson 6: Gathering Nutrition Information About Our Food

Grade 4 - Nutrition Lesson 5: Eating Right to Support Your Muscles and Skin Lesson 6: Gathering Nutrition Information about Our Food Objectives: 9 Students will identify foods as belonging to the carbohydrate, protein or fat food category. 9 Students will compare the carbohydrate, fat and protein value in various foods. 9 Students will learn to read nutritional facts on food labels. 9 Students will identify a balance of foods that support healthy muscles and skin. 9 Students will track and report their food and drink consumption during a week’s time. 9 Students will practice incorporating into their diet a balance of foods that support the muscles and skin. Materials: • Food Pyramid poster (www.mypyramid.gov) • Nutrition Facts labels for food from each of the Food Pyramid categories • Measuring cups • Journal or notebook for the Action Plan for Healthy Muscles and Skin— one per student • Poster boards • Magazines and newspapers with food pictures • Sample foods from each of the Pyramid categories • Bags with nutrition labels from chips, cookies, ice cream and other snack foods. • Milk containers (Low fat and chocolate) • Sand • Food and Nutrient Chart I –(Figure 1) • Food and Nutrient Chart II- (Figure 2) • Food and Nutrient Chart III – (Figure 3) • Nutrition Facts sample labels (11 labels) - (Figure 4) Activity Summary: In this lesson students will explore foods that support the development of healthy muscles and skin, focusing on variety and a balance of good foods in the diet. Students will sort foods into carbohydrate, protein and fat categories. Students will read nutrition facts labels and compare the carbohydrate, fat, and protein values of various foods.