Apalone Mutica) Hatchlings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

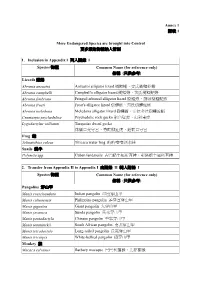

Annex 1 附表1 More Endangered Species Are Brought Into Control 更

Annex 1 附表 1 More Endangered Species are brought into Control 更多瀕危物種納入管制 1. Inclusion in Appendix I 列入附錄 I Species 物種 Common Name (for reference only) 俗稱 (只供參考) Lizards 蜥蜴 Abronia anzuetoi Anzuetoi alligator lizard 樹鱷蜥、安氏樹鱷蛇蜥 Abronia campbelli Campbell's alligator lizard 樹鱷蜥、坎氏樹鱷蛇蜥 Abronia fimbriata Fringed arboreal alligator lizard 樹鱷蜥、飾緣樹鱷蛇蜥 Abronia frosti Frost's alligator lizard 樹鱷蜥、弗氏樹鱷蛇蜥 Abronia meledona Meledona alligator lizard 樹鱷蜥、米拉多拉樹鱷蛇蜥 Cnemaspis psychedelica Psychedelic rock gecko 彩色壁虎、幻彩東虎 Lygodactylus williamsi Turquoise dwarf gecko 侏儒日光守宮、青藍柳趾虎、鈷藍日守宮 Frog 蛙 Telmatobius culeus Titicaca water frog 的的喀喀湖水蛙 Snails 蝸牛 Polymita spp. Cuban landsnails 古巴蝸牛屬所有種、彩條蝸牛屬所有種 2. Transfer from Appendix II to Appendix I 由附錄 II 轉入附錄 I Species 物種 Common Name (for reference only) 俗稱 (只供參考) Pangolins 穿山甲 Manis crassicaudata Indian pangolin 印度穿山甲 Manis culionensis Philippine pangolin 菲律賓穿山甲 Manis gigantea Giant pangolin 大穿山甲 Manis javanica Sunda pangolin 馬來穿山甲 Manis pentadactyla Chinese pangolin 中華穿山甲 Manis temminckii South African pangolin 南非穿山甲 Manis tetradactyla Long-tailed pangolin 長尾穿山甲 Manis tricuspis White-bellied pangolin 樹穿山甲 Monkey 猴 Macaca sylvanus Barbary macaque 巴巴利獼猴、北非獼猴 Parrot 鸚鵡 Psittacus erithacus African grey parrot 非洲灰鸚鵡 Lizard 蜥蜴 Shinisaurus crocodilurus Chinese crocodile lizard 瑤山鱷蜥 Plants 植物 Sclerocactus blainei Blaine's fishhook cactus 布氏白虹山 Sclerocactus cloverae New Mexico fishhook cactus 新墨西哥鯱玉 Sclerocactus sileri Siler's fishhook cactus 塞氏鯱玉 3. Transfer from Appendix I to Appendix II 由附錄 I 轉入附錄 II Species 物種 Common Name (for reference only) 俗稱 (只供參考) Mammals 哺乳類 Puma concolor coryi Florida cougar, Florida puma 美洲獅佛羅里達亞種 Puma concolor couguar Eastern cougar, eastern puma 美洲獅東部亞種 Equus zebra zebra Cape mountain zebra 山斑馬指名亞種 Ave s 鳥類 Lichenostomus melanops cassidix Helmeted honeyeater 黃披肩吸蜜鳥卡西迪亞種 Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata Norfolk boobook 布布克鷹鴞諾福克島亞種 Crocodiles 鱷魚 Crocodylus acutus 1 American crocodile 窄吻鱷 Crocodylus porosus 2 Estuarine crocodile 灣鱷 Frog 蛙 Dyscophus antongilii Tomato frog 安通吉爾灣姬蛙 4. -

Nilssonia Leithii (Gray 1872) – Leith's Softshell Turtle

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project ofTrionychidae the IUCN/SSC Tortoise— Nilssonia and Freshwater leithii Turtle Specialist Group 075.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.075.leithii.v1.2014 © 2014 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 17 February 2014 Nilssonia leithii (Gray 1872) – Leith’s Softshell Turtle INDRANE I L DAS 1, SHASHWAT SI RS I 2, KARTH ik EYAN VASUDE V AN 3, AND B.H.C.K. MURTHY 4 1Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia [[email protected]]; 2Turtle Survival Alliance-India, D-1/316 Sector F, Janakipuram, Lucknow 226 021, India [[email protected]]; 3Laboratory for Conservation of Endangered Species, Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Pillar 162, PVNR Expressway, Hyderguda, Hyderabad 500 048, India [[email protected]]; 4Zoological Survey of India, J.L. Nehru Road, Kolkata 700 016, India [[email protected]] SU mm ARY . – Leith’s Softshell Turtle, Nilssonia leithii (Family Trionychidae), is a large turtle, known to attain at least 720 mm in carapace length (bony disk plus fibrocartilage flap), and possibly as much as 1000 mm. The species inhabits the rivers and reservoirs of southern peninsular India, replacing the more familiar Indian Softshell Turtle, N. gangetica, of northern India. The turtle is apparently rare within its range, even within protected areas, which is suspected to be due to a past history of exploitation. -

Turtle Monitoring Turtle Notching Image of Turtle Trap

Monitoring Turtles at Nygren Wetland Preserve India John ’12, Beloit College Sustainability Fellows Program [1,2] Summer 2010 Blanding’s Turtle Painted Turtle [1,2] Emydoidea blandingii Chrysemys picta Turtle Monitoring Size: 6-10 inch carapace Habitat: Shallow marshy areas •Four traps made by volunteers set throughout the with abundant submerged preserve vegetation; semi-terrestrial •Traps were checked 3-4 times a week Temperament: Docile and shy •Traps were moved frequently throughout the property Status: State Threatened Species, •Captured turtles were: despite reported sightings, no • weighed Blanding’s turtles have been • measured (plastron and carapace length and width) captured or recorded at Nygren. Plastron (bottom of shell) • notched (Painted Turtles only) of Midland Painted Turtle • released Blanding’s Turtle in Boone County Midland Painted Turtle Photo by: India John Photo by Courtney Schultz Photo by Courtney Schultz Two subspecies in Wisconsin: [1,2] Midland Painted ( Chrysemys picta marginata ) Softshell Turtle Western Painted ( Chrysemys picta bellii ). Apalone Size: 4-8 inch carapace Image Habitat: Marshes and ponds, with dense aquatic vegetation of Temperament: Docile Status: Common; the Western Painted is the turtle most abundant turtle in Wisconsin. Plastron of a Western trap Painted Turtle Photo by India John Snapping Turtle [1,2] Carapace (top of shell) of a Interns India John and Scott Kruger making turtle traps Eastern Spiny Softshell turtle Smooth Softshell turtle Chelydra serpentina Photo by Courtney Schultz Photo by Greg Keilback Photo by India John Two species: Eastern Spiny Softshell (Apalone spinifera ), Turtle Notching Smooth Softshell ( Apalone muticus ) Size: Spiny - carapace: fem. 7 - 18 in., Marked individual turtles by notching the m. -

RELATIVE ABUNDANCE of SPINEY SOFTSHELL TURTLES (Apalone Spinifera) on the MISSOURI and YELLOWSTONE RIVERS in MONTANA FINAL REPOR

RELATIVE ABUNDANCE OF SPINEY SOFTSHELL TURTLES (Apalone spinifera) ON THE MISSOURI AND YELLOWSTONE RIVERS IN MONTANA FINAL REPORT Arnold R. Dood, Brad Schmitz, Vic Riggs, Nate McClenning, Matt Jeager, Dave Fuller, Ryan Rauscher, Steve Leathe, Dave Moore, JoAnn Dullum, John Ensign, Scott Story, Mike Backes Abstract In 2003, the Missouri River Natural Resources Committee (MRNRC) Wildlife Section advocated developing a survey for the relative abundance of softshell turtles (Apalone sp.) on the Missouri River system. Softshell turtles were selected because they occur throughout the system and there was some information suggesting that they may have been impacted by system operations. As a common riverine species, there were possibilities that softshell turtles may have been impacted because of the timing, level, and temperature of river flows as well as by dam construction and bank stabilization. In addition, there were reports from other areas in the species range that they may be especially sensitive to human disturbance. From 2004 through 2008, State and Federal agencies and Pacific Power and Light in Montana sampled the Missouri River from Great Falls, MT, to the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone (except Fort Peck Reservoir) as well as they Yellowstone River from above Billings to the confluence. Sampling consisted of setting turtle traps every two river miles and checking for three days. Turtles captured were measured, marked, and released. Results of the sampling efforts indicated high relative densities above Fort Peck Reservoir and variable densities on the Yellowstone. No spiny softshells were found below Fort Peck or on the Yellowstone below Sidney, MT. Possible reasons are presented and recommendations for future program direction as well as potential system modifications to benefit this species are discussed. -

Parasites of Florida Softshell Turtles (Apalone Ferox} from Southeastern Florida

J. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 65(1), 1998 pp. 62-64 Parasites of Florida Softshell Turtles (Apalone ferox} from Southeastern Florida GARRY W. FOSTER,1-3 JOHN M. KINSELLA,' PAUL E. MoLER,2 LYNN M. JOHNSON,- AND DONALD J. FORRESTER' 1 Department of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611 (e-mail:[email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]) and 2 Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission, Gainesville, Florida 32601 (e-mail: pmoler®wrl.gfc.state.fi.us) ABSTRACT: A total of 15 species of helminths (4 trematodes, 1 monogenean, 1 cestode, 5 nematodes, 4 acan- thocephalans) and 1 pentastomid was collected from 58 Florida softshell turtles (Apalone ferox) from south- eastern Florida. Spiroxys amydae (80%), Cephalogonimiis vesicaudus (80%), Vasotrema robiistum (76%), and Proteocephalus sp. (63%) were the most prevalent helminths. Significant lesions were associated with the at- tachment sites of Spiroxys amydae in the stomach wall. Contracaecum multipapillatum and Polymorphus brevis are reported for the first time in reptiles. The pentastomid Alofia sp. is reported for the first time in North America and in turtles. KEY WORDS: Softshell turtle, Apalone ferox, helminths, pentastomes, Florida. The Florida softshell turtle (Apalone ferox) softshell turtles from southeastern Florida are ranges from southern South Carolina, through discussed. southern Georgia to Mobile Bay, Alabama, and all of Florida except the Keys (Conant and Col- Methods lins, 1991). Where it is sympatric with the Gulf A total of 58 Florida softshell turtles was examined. Coast spiny softshell turtle (Apalone spinifera Fifty-seven were obtained from a commercial proces- asperd) in the Florida panhandle, the Florida sor in Palm Beach County, Florida, between 1993 and softshell is found more often in lacustrine hab- 1995. -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 100/Tuesday, May 24, 2016/Rules

32664 Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 100 / Tuesday, May 24, 2016 / Rules and Regulations Date certain Federal assist- State and location Community Effective date authorization/cancellation of Current effective ance no longer No. sale of flood insurance in community map date available in SFHAs Bonita, Village of, Morehouse Parish ........... 220316 April 3, 1997, Emerg; April 1, 2007, Reg; ......do ............... Do. July 6, 2016, Susp. Collinston, Village of, Morehouse Parish ..... 220399 June 17, 1991, Emerg; N/A, Reg; July 6, ......do ............... Do. 2016, Susp. Mer Rouge, Village of, Morehouse Parish ... 220128 May 3, 1973, Emerg; June 27, 1978, Reg; ......do ............... Do. July 6, 2016, Susp. Morehouse Parish, Unincorporated Areas ... 220367 April 14, 1983, Emerg; October 15, 1985, ......do ............... Do. Reg; July 6, 2016, Susp. New Mexico: Dona Ana County, Unincor- 350012 January 19, 1976, Emerg; September 27, ......do ............... Do. porated Areas. 1991, Reg; July 6, 2016, Susp. Hatch, Village of, Dona Ana County ............ 350013 December 10, 1974, Emerg; January 3, ......do ............... Do. 1986, Reg; July 6, 2016, Susp. Las Cruces, City of, Dona Ana County ........ 355332 July 24, 1970, Emerg; June 11, 1971, Reg; ......do ............... Do. July 6, 2016, Susp. Mesilla, Town of, Dona Ana County ............. 350113 March 7, 1975, Emerg; May 28, 1985, Reg; ......do ............... Do. July 6, 2016, Susp. Sunland Park, City of, Dona Ana County ..... 350147 N/A, Emerg; November 8, 2006, Reg; July ......do ............... Do. 6, 2016, Susp. *.....do = Ditto. Code for reading third column: Emerg. —Emergency; Reg. —Regular; Susp. —Suspension. Dated: May 12, 2016. species (including their subspecies, in September 2010, to discuss the Michael M. -

Cultural Exploitation of Freshwater Turtles in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo

NOTES AND FIELD REPORTS 281 determination in turtles: ecological and behavioral aspects. (e.g., Das 1991, 1994), recovery of undescribed turtle Herpetologica 38:156–164. species has been reported from human material remains in WATERS, J.C. 1974. The biological significance of the basking some localities, such as one in Zaire (Meylan 1990). In a habit in the black-knobbed sawback, Graptemys nigrinoda Cagle. MSc Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama. contemporary context, human utilization of turtles is both WEBB, R.G. 1961. Observations on the life histories of turtles widespread and locally intensive where populations permit (Genus Pseudemys and Graptemys) in lake Texoma, Oklaho- their use, leading to serious conservation problems ma. American Midland Naturalist 65:193–214. (Thorbjarnarson et al. 2000). Most of the attention to the global turtle crisis has Received: 10 July 2007 been directed to China, the primary consumer of turtles in Revised and Accepted: 23 September 2008 recent years, rather than to most other adjacent or regional Asian countries, which are the sources or potential sources of turtles in the trade. One such area is Borneo, the world’s third largest island, located in the Malay Archipelago and Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 2008, 7(2): 281–285 considered a center of global biodiversity. The island is Ó 2008 Chelonian Research Foundation under the jurisdiction of three countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei Darussalam. Sarawak is one of the Cultural Exploitation of Freshwater Turtles 2 Malaysian states located on the island (Fig. 1), the other in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo being Sabah. The dominant ethnic group of Sarawak is Iban; other important indigenous groups include the 1,2 1 Bidayuh, Kelabit, Lun Bawang, Melenau, Kenyah, Kayan, KAREN A. -

A Field Guide to South Dakota Turtles

A Field Guide to SOUTH DAKOTA TURTLES EC919 South Dakota State University | Cooperative Extension Service | USDA U.S. Geological Survey | South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit South Dakota Department of Game, Fish & Parks This publication may be cited as: Bandas, Sarah J., and Kenneth F. Higgins. 2004. Field Guide to South Dakota Turtles. SDCES EC 919. Brookings: South Dakota State University. Copies may be obtained from: Dept. of Wildlife & Fisheries Sciences South Dakota State University Box 2140B, NPBL Brookings SD 57007-1696 South Dakota Dept of Game, Fish & Parks 523 E. Capitol, Foss Bldg Pierre SD 57501 SDSU Bulletin Room ACC Box 2231 Brookings, SD 57007 (605) 688–4187 A Field Guide to SOUTH DAKOTA TURTLES EC919 South Dakota State University | Cooperative Extension Service | USDA U.S. Geological Survey | South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit South Dakota Department of Game, Fish & Parks Sarah J. Bandas Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences South Dakota State University NPB Box 2140B Brookings, SD 57007 Kenneth F. Higgins U.S. Geological Survey South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit South Dakota State University NPB Box 2140B Brookings, SD 57007 Contents 2 Introduction . .3 Status of South Dakota turtles . .3 Fossil record and evolution . .4 General turtle information . .4 Taxonomy of South Dakota turtles . .9 Capturing techniques . .10 Turtle handling . .10 Turtle habitats . .13 Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta bellii) . .15 Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) . .17 Spiny Softshell Turtle (Apalone spinifera) . .19 Smooth Softshell Turtle (Apalone mutica) . .23 False Map Turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) . .25 Western Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata ornata) . -

Federal Register/Vol. 79, No. 210/Thursday, October 30, 2014

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 210 / Thursday, October 30, 2014 / Proposed Rules 64553 incremental NGCC generation identified generation levels. Together, the same information sources and presented under building block 2 (given that under approach in the proposal and the in the same format as the 2012 dataset the proposal, generation from building alternative approach in this document used for the June 2014 proposed rule. block 2 was assumed to reduce carbon reflect a range of possible emission rate We are also making these data available intensity by replacing generation from impacts that could be expected through at: http://www2.epa.gov/ 2012 levels). The rationale for this the application of the incremental RE cleanpowerplan/. approach would be that the BSER for all and EE in the state goal calculation. The Dated: October 27, 2014. fossil generation includes replacing that EPA is seeking comment on which Janet G. McCabe, generation with incremental RE and EE. approach better reflects the BSER. At Moreover, this approach acknowledges the same time, we note that the Acting Assistant Administrator, Office of Air and Radiation. that, taken by itself, such incremental alternative state goal formula generation would not necessarily approaches listed here may raise a [FR Doc. 2014–25845 Filed 10–29–14; 8:45 am] replace the highest-emitting generation, number of additional considerations. BILLING CODE 6560–50–P but would likely replace a mix of These approaches, for example, would existing fossil generating technologies. increase the collective stringency of the b. Prioritize replacement of historical state goals, which would likely increase DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR fossil steam generation. -

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2013–0052]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3050/docket-no-fws-hq-es-2013-0052-2093050.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2013–0052]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 05/24/2016 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2016-11201, and on FDsys.gov Billing Code 4333–15 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 23 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2013–0052] RIN 1018–AZ53 Inclusion of Four Native U.S. Freshwater Turtle Species in Appendix III of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), are listing the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina), Florida softshell turtle (Apalone ferox), smooth softshell turtle (Apalone mutica), and spiny softshell turtle (Apalone spinifera) in Appendix 1 III of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES or Convention), including live and dead whole specimens, and all readily recognizable parts, products, and derivatives. Listing these four native U.S. freshwater turtle species (including their subspecies, except Apalone spinifera atra, which is already included in Appendix I of CITES) in Appendix III of CITES is necessary to allow us to adequately monitor international trade in these species; to determine whether exports are occurring legally, with respect to State and Federal law; and to determine whether further measures under CITES or other laws are required to conserve these species and their subspecies. DATES: This listing is effective [INSERT DATE 180 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESSES: You may obtain information about permits for international trade in these species and their subspecies by contacting the U.S. -

Chelonian Advisory Group Regional Collection Plan 4Th Edition December 2015

Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) Chelonian Advisory Group Regional Collection Plan 4th Edition December 2015 Editor Chelonian TAG Steering Committee 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Mission ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Steering Committee Structure ........................................................................................................... 3 Officers, Steering Committee Members, and Advisors ..................................................................... 4 Taxonomic Scope ............................................................................................................................. 6 Space Analysis Space .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Survey ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Current and Potential Holding Table Results ............................................................................. 8 Species Selection Process Process ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Decision Tree ........................................................................................................................... 13 Decision Tree Results ............................................................................................................. -

Turtles of the World, 2010 Update: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTurtles of the IUCN/SSC of the World Tortoise – 2010and Freshwater Checklist Turtle Specialist Group 000.85 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v3.2010 © 2010 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 14 December 2010 Turtles of the World, 2010 Update: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status TUR T LE TAXONOMY WORKING GROUP * *Authorship of this article is by this working group of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, which for the purposes of this document consisted of the following contributors: ANDERS G.J. RHODIN 1, PE T ER PAUL VAN DI J K 2, JOHN B. IVERSON 3, AND H. BRADLEY SHAFFER 4 1Chair, IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, Chelonian Research Foundation, 168 Goodrich St., Lunenburg, Massachusetts 01462 USA [[email protected]]; 2Deputy Chair, IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, Virginia 22202 USA [[email protected]]; 3Department of Biology, Earlham College, Richmond, Indiana 47374 USA [[email protected]]; 4Department of Evolution and Ecology, University of California, Davis, California 95616 USA [[email protected]] AB S T RAC T . – This is our fourth annual compilation of an annotated checklist of all recognized and named taxa of the world’s modern chelonian fauna, documenting recent changes and controversies in nomenclature, and including all primary synonyms, updated from our previous three checklists (Turtle Taxonomy Working Group [2007b, 2009], Rhodin et al.