Origin of the Nagas in Manipur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNICEF Support to the COVID-19 Surge in India As Part of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A)

UNICEF support to the COVID-19 surge in India as part of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) The reach and capacity of the cold chain system in India is strengthened to sustain the massive COVID- 19 vaccine drive • UNICEF has worked at the request of MoHFW to augment the cold chain network across the country since third quarter of 2020. In preparation of the launch of vaccination drive, additional cold chain equipment, such as a Walk-In Cold Rooms (WIC), Walk-In Freezer Rooms (WIF), fridges and deep freezers were procured to enhance vaccine storage at all levels. Vaccine transportation passive devices (cold box/vaccine carriers) were also procured to support the vaccination rollout. • The vaccine rollout was launched nationwide on the 16th of January 2021, with priority to Health Care Workers, Frontline Workers and people aged 60 years and above. On 1st April 2021, vaccination was made available to those above the age of 45. Over 156 million vaccine doses have been administered as of 1st May 2021, Day 106 of the vaccination campaign, making India the country with the fastest vaccination scale up in the world. • As of May 1st, vaccine eligibility has been expanded to all above the age of 18. With this expansion and to support equitable access to vaccination even in remote areas, UNICEF will/ plans to further augment bulk storage sites by providing additional equipment (WIC/WIF) along with Solar Direct Drive (SDD) Fridges for remote locations with limited power supply. • Current COVID-19 vaccines in use in India are freeze sensitive. -

The Situation of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in India

Joint Stakeholders’ submission on The situation of the rights of indigenous peoples in India For 3rd cycle of the Universal Period Review (UPR) of India 27th Session of the Human Rights Council (Apr-May 2017) Submitting organizations (in alphabetical order)1 1. Adivasi Women’s Network (AWN) (Email: [email protected]; [email protected]) 1st Lane, Don Bosco, Kokar, Khohar Toli, Ranchi, Jharkhand 834001, India) 2. Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) (Website: www.aippnet.org; Email: [email protected]; Address: 108 Moo 5, T. San Phranet, A. Sansai, Chiang Mai 50210, Thailand) 3. Borok Peoples Human Rights Organization (BPHRO) (Email: [email protected]; Address: Palace Compound, Post Box No. 80, Agartala-1, Tripura, India) 4. Centre for Research and Advocacy (CRA) Manipur (Website: www.cramanipur.org; Email: [email protected]; Address: Sega Road Hodam Leirak Imphal Manipur 795001 India) 5. Chhattisgarh Tribal Peoples Forum (CTPF) (Email: [email protected]) 6. Indigenous Peoples Forum, Odisha (IPFO) (Email: [email protected]) 7. Jharkhand Indigenous and Tribal Peoples for Action (JITPA) (Email: [email protected]; Address: At Hehal Delatoli, Itki Road, PO Hehal, Ranchi Jharkhand 834005 India) 8. Karbi Human Rights Watch (KHRW) (Email: [email protected]; [email protected]) 9. Meghalaya Peoples Human Rights Council (MPHRC) (Email: [email protected]; Address: Mawlai-Mawroh, Shillong, Meghalaya 793008, India) 10. Naga Peoples Movement For Human Rights (NPMHR) (Email: [email protected], [email protected]; Address: Kohima, Nagaland 797005, India) 11. Zo Indigenous Forum (ZIF) (Website: http://zoindigenous.blogspot.com/; Email: [email protected]; Address: MZP Pisa Pui, Treasury Square, Aizawl, Mizoram 796001, India) 1 The preparation of this joint submission was led by AIPP and ZIF with inputs and endorsements from other organizations through online and in-person consultations. -

Imphal East Manipur |

DISTRICTDISTRICT NUTRITION NUTRITION PROFILE PROFILE Bi Imphal East|Manipur DISTRICT DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE1 5 Total Population 4,56,113 6 M0 Census 2011 Male Female 749.6%Fe1 Census 2011 50.4% 8 U # Census 2011 9UrbanRu1 Census 2011 Rural #40.2%SC0 Census 2011 59.8% # ST0 Census 2011 SC# O 1ST Census 2011 Others Imphal East ranks 141 amongst 599 3.5% # In6.1%#0 90.5% districts in India² THE STATE OF NUTRITION IN IMPHAL EAST UNDERNUTRITION3 100 Imphal East Manipur 75MImphal East # St ##NFHS4 50 %# W 78NFHS4 26.2 27.3 # U ##NFHS4 20.8 25 17.1 # An##NFHS4 7.8 NO DISTRICT LEVEL DATA 9.7 # Lo07#RSOC # An##NFHS4Stunting Wasting Underweight Anemia Low birth weight Anemia among Women with body (among children <5 (among children <5 (among children <5 (among children <5 (<2500 g) women of mass index <18.5 # W 9#NFHS4years) years) years) years) reproductive age kg/m2 # BMPOSSIBLE##NFHS4 POINTS OF DISCUSSION (WRA) # BM##NFHS4 How does the district perform on stunting, wasting, underweight and anemia among children under the age of 5? # H ##WhatNFHS4 are the levels of anemia prevalence and low body mass index among women? # H ##WhatNFHS4 are the levels of overweight/obesity and other nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in the district? # H 88NFHS4 OVERWEIGHT/OBESITY & NON-COMMUNICABLE DISEASES (15-49 y)4 # 100H 9#NFHS4 75 % 50 30.8 22.2 22.4 25 12 8 11.3 0 BMI >25 kg/m2 BMI >25 kg/m2 High blood pressure High blood pressure High blood sugar High blood sugar among women among men among women among men among women among men (15-49 years) (15-49 -

THE LANGUAGES of MANIPUR: a CASE STUDY of the KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE LANGUAGES OF MANIPUR: A CASE STUDY OF THE KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar Abstract: Manipur is primarily the home of various speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages. Aside from the Tibeto-Burman speakers, there are substantial numbers of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian speakers in different parts of the state who have come here either as traders or as workers. Keeping in view the lack of proper information on the languages of Manipur, this paper presents a brief outline of the languages spoken in the state of Manipur in general and Kuki-Chin languages in particular. The social relationships which different linguistic groups enter into with one another are often political in nature and are seldom based on genetic relationship. Thus, Manipur presents an intriguing area of research in that a researcher can end up making wrong conclusions about the relationships among the various linguistic groups, unless one thoroughly understands which groups of languages are genetically related and distinct from other social or political groupings. To dispel such misconstrued notions which can at times mislead researchers in the study of the languages, this paper provides an insight into the factors linguists must take into consideration before working in Manipur. The data on Kuki-Chin languages are primarily based on my own information as a resident of Churachandpur district, which is further supported by field work conducted in Churachandpur district during the period of 2003-2005 while I was working for the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, as a research investigator. -

Imphal West District, Manipur

Technical Report Series: D No: 28/2013-14 Ground Water Information Booklet Imphal West District, Manipur Central Ground Water Board North Eastern Region Ministry of Water Resources Guwahati September 2013 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET IMPHAL WEST DISTRICT, MANIPUR DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl. Items Statistics No 1. General information i) Geographical area (sq. km.) 558 ii) Administrative Divisions as on 3 31 March 2013 Number of Tehsils/CD Blocks 2 Number of Panchayat/Village 1/117 iii) Population as per 2011 census 5,14,683 iv) Average annual rainfall in mm 1632.40 2. Geomorphology i) Major physiographic units i) Imphal west plain, marshy land and low to high altitude structural hills. ii) Imphal, ii) Major drainages Nambul Rivers and its tributaries. 3. Land use in sq. km. i) Forest area 57.00 ii) Net area sown Undivided Imphal District : 834.01 iii) Cultivable area Undivided Imphal District : 861.91 4. Major soil types Alluvial soil 5. Area under principal crops in sq. km as Data not available on March 2011 6. Irrigation by different sources Data not available a) surface water b) ground water 7. Numbers of monitoring wells of CGWB 3 National Hydrograph Stations of CGWB in as on 31.03.13 Imphal West that are regularly monitored prior to 1991. No monitoring work is carried out since 1991 due to disturbed law and order situation in the state. 8. Predominant nt geological formations Quaternary formation followed b y Tertiary deposits. 9. Hydrogeology i) Intermontane alluvial formation of i) Major water bearing formations river borne deposit along the rivers followed by Tertiary formation ii) Pre-monsoon water level (structurally iii) Post monsoon water level weak zones). -

Some Anti-Diarrhoeic and Anti-Dysenteric Ethno-Medicinal Plants of Mao Naga Tribe Community of Mao, Senapati District, Manipur

Available online at www.ijpab.com ISSN: 2320 – 7051 Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 2 (1): 147-155 (2014) Research Article International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience Some Anti-diarrhoeic and Anti-dysenteric Ethno-medicinal Plants of Mao Naga Tribe Community of Mao, Senapati District, Manipur 1* 2 Sunita Gurumayum and Jiten Singh Soram 1Dept. of Botany, Asufii Christian Institute, Mao, Senapati District, Manipur-795150 2Dept. of Zoology, Asufii Christian Institute, Mao, Senapati District, Manipur-795150 *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Diarrhoea and dysentery are the important causes of mortality in the developing countries till today. On the other hand, Manipur state as a whole lies in the Indo-Burma Biodiversity hot spot owing to which harbours diverged plants supporting about 50% of India’s biodiversity. Mao Naga tribe inhabits the Mao area, located at a unique geographic, climatic and topographical area in Senapati district of Manipur. The people of Mao Naga tribe think themselves to have migrated from China through oral storytelling and have a distinct colourful culture and tradition in which traditional system of medicine forms a large part. However, this vast body of ethno-botanical knowledge has remained largely unexplored. Thus, an ethno-medicinal survey has been conducted with the help of local volunteers and accordingly this paper has a record of 45 plant species being used in traditional medicine belonghing 41 genera and 28 families for treating diarrhoea and dysentery. The family Asteraceae has maximum species representation of six followed by the family Zingiberaceae with five recorded species. Leaves were the maximum parts used compared to the other parts with their 34.3% usage, followed by fruit (15%) and bark (12%).The study also showed an immense potential for ethno-botanical research in the area. -

Identity Politics and Social Exclusion in India's North-East

Identity Politics and Social Exclusion in India’s North-East: The Case for Re-distributive Justice N.K.Das• Abstract: This paper examines how various brands of identity politics since the colonial days have served to create the basis of exclusion of groups, resulting in various forms of rifts, often envisaged in binary terms: majority-minority; sons of the soil’-immigrants; local-outsiders; tribal-non-tribal; hills-plains; inter-tribal; and intra-tribal. Given the strategic and sensitive border areas, low level of development, immense cultural diversity, and participatory democratic processes, social exclusion has resulted in perceptions of marginalization, deprivation, and identity losses, all adding to the strong basis of brands of separatist movements in the garb of regionalism, sub-nationalism, and ethnic politics, most often verging on extremism and secession. It is argued that local people’s anxiety for preservation of culture and language, often appearing as ‘narcissist self-awareness’, and their demand of autonomy, cannot be seen unilaterally as dysfunctional for a healthy civil society. Their aspirations should be seen rather as prerequisites for distributive justice, which no nation state can neglect. Colonial Impact and genesis of early ethnic consciousness: Northeast India is a politically vital and strategically vulnerable region of India. Surrounded by five countries, it is connected with the rest of India through a narrow, thirty-kilometre corridor. North-East India, then called Assam, is divided into Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura. Diversities in terms of Mongoloid ethnic origins, linguistic variation and religious pluralism characterise the region. This ethnic-linguistic-ecological historical heritage characterizes the pervasiveness of the ethnic populations and Tibeto-Burman languages in northeast. -

Manual of Instructions for Editing, Coding and Record Management of Individual Slips

For offiCial use only CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 MANUAL OF INSTRUCTIONS FOR EDITING, CODING AND RECORD MANAGEMENT OF INDIVIDUAL SLIPS PART-I MASTER COPY-I OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL&. CENSUS COMMISSIONER. INOI.A MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI CONTENTS Pages GENERAlINSTRUCnONS 1-2 1. Abbreviations used for urban units 3 2. Record Management instructions for Individual Slips 4-5 3. Need for location code for computer processing scheme 6-12 4. Manual edit of Individual Slip 13-20 5. Code structure of Individual Slip 21-34 Appendix-A Code list of States/Union Territories 8a Districts 35-41 Appendix-I-Alphabetical list of languages 43-64 Appendix-II-Code list of religions 66-70 Appendix-Ill-Code list of Schedules Castes/Scheduled Tribes 71 Appendix-IV-Code list of foreign countries 73-75 Appendix-V-Proforma for list of unclassified languages 77 Appendix-VI-Proforma for list of unclassified religions 78 Appendix-VII-Educational levels and their tentative equivalents. 79-94 Appendix-VIII-Proforma for Central Record Register 95 Appendix-IX-Profor.ma for Inventory 96 Appendix-X-Specimen of Individual SHp 97-98 Appendix-XI-Statement showing number of Diatricts/Tehsils/Towns/Cities/ 99 U.AB.lC.D. Blocks in each State/U.T. GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS This manual contains instructions for editing, coding and record management of Individual Slips upto the stage of entry of these documents In the Direct Data Entry System. For the sake of convenient handling of this manual, it has been divided into two parts. Part·1 contains Management Instructions for handling records, brief description of thf' process adopted for assigning location code, the code structure which explains the details of codes which are to be assigned for various entries in the Individual Slip and the edit instructions. -

THE NAGA TRIBES of MANIPUR MACMILLAN and CO., Limited

^ s^ ^ ^S5 <rii30NYS01^ '^Aa3AINn-3WV^ ^OFCALIFO/?^ ^OFCALIFO/?^ .^MEllNIVERS//, vvlOSANCEl5j> 4? (—1 >-"- =0 CJ ^^„. "^...•§' ^.r:'. v!? <rn3'}Nvsoi^'^ '^Aa]AiNn-3WV y CD u_ CALIFO% .^OF-CALIFOP ^• ?7 ^ ' iiiJ'JNV^Ul' A\AfUNIVER5-//,'/- '? i S ^ J^' ^OFCAIIFO/?^ — < V' ?3 <:::; «-£:-• 'i^^Ayvaaii-^^^ AWEUNIVFR'T//. ^ g1<i? CO .^MEUMIVERS/a vvlO'^AvrFir. *^PCAllFO/?;l^ ^.OF-CAi^Fn;,.., ^tllBRARYQ^ ^illBRARYQ-c \V\E UNIVERi/A vj<lOSANCElfj> 'Jr \ cxrT^ 8 ^viy M s^ ^. s^ ^Aa3,MN(l-3WV^ %dllV3J0>^ ^OFCAtlFO/?^ o ^AdiAlNH 3\\V .VlOSANCElfXy. AMFUNIVERS//, o %a3AIN(13\\V '^«!/0JllV3JO'<^ '^<!/0JllV3 JO"^ v>;lOSANCElfj> ^.OFCAIIFO/?^ .>;,OFCAllFOfi>iA ,\WEUNIVER57a >5^ •^. "^/^ajAiNn-jwv^ "^o-mnw^ '^ommy^' <rji]ONvsoi^^ ^ILIBRARYQ^^ AMEUNIVER% .vWSANCElfj> ^IIIBRARYO/^ •^(i/ojnvDjo^^ <rii30Nvsoi^ "^iieAiNfi-juv^ \s)i\mi^^ ^0FCAIIF0%. ^WEUNIVERi-/^ vvlOSANCElfj> ^.OFCAllFOff^ ^riijoNVsoi^"^ ^/^a3AiNn-3WV^ ^>&Aava8ii#^ .>;lOSANCElfj> -<^A^IIBRARY(9/^ ^^^LIBRARYQ/: AME UNIVERS"//, o %S3AINf)3UV ^.!/0JnV3J0^ '^.'/OJIIVJJO^' <Q130NVS01^^ .vWSANCElfx> ^OFCALIF0% ^•OF CALIFO/?^ ^^\AEUMIVERy/4 '^AJ13AINn-3W^' ^vSlLIBRARYQ^ . ^WE UNIVERV/, .VWSANCEI/J> ^^ILIBRARYO^ 3 1 rr" ^ >^\ § 1 ir-^ ^ THE NAGA TRIBES OF MANIPUR MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON . BOMBAY . CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK . BOSTON . CHICAGO ATLANTA . SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO TANGKHUL KHULLAKPAS CLOTH. Sec p. 22. Frontispiece. THE NAGA tribes OF MANIPUR T. C. HODSON Late Assistant Political Agent in Manipur and Superintendent ofthe -

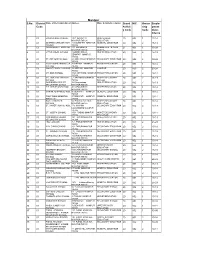

Manipur S.No

Manipur S.No. District Name of the Establishment Address Major Activity Description Broad NIC Owner Emplo Code Activit ship yment y Code Code Class Interva l 101OKLONG HIGH SCHOOL 120/1 SENAPATI HIGH SCHOOL 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795104 EDUCATION 201BETHANY ENGLISH HIGH 149 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795104 301GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL 125 MAKHRALUI HUMAN HEALTH CARE 21 861 1 30-99 MANIPUR 795104 CENTRE 401LITTLE ANGEL SCHOOL 132 MAKHRELUI, HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SENAPATI MANIPUR 795106 501ST. ANTHONY SCHOOL 28 MAKHRELUI MANIPUR SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 30-99 795106 601TUSII NGAINI KHUMAI UJB 30 MEITHAI MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 1 10-14 SCHOOL 795106 701MOUNT PISGAH COLLEGE 14 MEITHAI MANIPUR COLLEGE 20 853 2 20-24 795106 801MT. ZION SCHOOL 47(2) KATHIKHO MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 2 10-14 795106 901MT. ZION ENGLISH HIGH 52 KATHIKHO MANIPUR HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795106 SCHOOL 10 01 DON BOSCO HIGHER 38 Chingmeirong HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 7 15-19 SECONDARY SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 11 01 P.P. CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 40 LAIROUCHING HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795105 12 01 MARAM ASHRAM SCHOOL 86 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 795105 13 01 RANGTAIBA MEMORIAL 97 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 853 1 10-14 INSTITUTE 795105 14 01 SAINT VINCENT'S 94 PUNGDUNGLUNG HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 10-14 SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 EDUCATION 15 01 ST. XAVIER HIGH SCHOOL 179 MAKHAN SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 LOVADZINHO MANIPUR 795105 16 01 ST. -

Distribution of ABO Blood Groups and Rhesus Factor Percentage

Published Online on 21 March 2017 Proc Indian Natn Sci Acad 83 No. 1 March 2017 pp. 217-222 Printed in India. DOI: 10.16943/ptinsa/2017/41289 Research Paper Distribution of ABO Blood Groups and Rhesus Factor Percentage Frequencies Amongst the Populations of Sikkim, India JAYANTI RAI and BISU SINGH* Department of Zoology, School of Life Sciences, Sikkim University, Samdur, Tadong, Gangtok 737 102, Sikkim, India (Received on 23 September 2016; Revised on 24 October 2016; Accepted on 20 December 2016) The incidence of ABO and Rh blood group has been found to vary in various populations. The present investigation was undertaken with the aim to study ABO blood group frequency amongst a subset of population of Sikkim. A total of 5098 individuals were included in the study out of which 215 were students of Department of Zoology, Sikkim University and Government College, Tadong, East Sikkim, 3000 individuals were from Rinchenpong and 1883 individuals were from Bermiok, Berfok, Berthang, Martam, Chingthang, Deythang, Hatidhunga, Samdong, Sangadorjee and Yangsum of West Sikkim. The data for ABO blood group were collected from the register of Primary Health Centre, Rinchenpong and others by documenting blood group of the individuals who have undergone routine blood group testing in diagnostic laboratories. SPSS software Version 8 was used to perform statistical analysis. The results were calculated as frequencies of each of the blood group, expressed as percentages. The frequency of blood group A (35.34%) was found to be the highest, followed by blood group O (35.18%), B (21.99%) and AB (7.49%). The results also indicated that 99.47% of individuals were Rh positive and 0.53 % were Rh negative. -

Languages of Southeast Asia

Jiarong Horpa Zhaba Amdo Tibetan Guiqiong Queyu Horpa Wu Chinese Central Tibetan Khams Tibetan Muya Huizhou Chinese Eastern Xiangxi Miao Yidu LuobaLanguages of Southeast Asia Northern Tujia Bogaer Luoba Ersu Yidu Luoba Tibetan Mandarin Chinese Digaro-Mishmi Northern Pumi Yidu LuobaDarang Deng Namuyi Bogaer Luoba Geman Deng Shixing Hmong Njua Eastern Xiangxi Miao Tibetan Idu-Mishmi Idu-Mishmi Nuosu Tibetan Tshangla Hmong Njua Miju-Mishmi Drung Tawan Monba Wunai Bunu Adi Khamti Southern Pumi Large Flowery Miao Dzongkha Kurtokha Dzalakha Phake Wunai Bunu Ta w an g M o np a Gelao Wunai Bunu Gan Chinese Bumthangkha Lama Nung Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Norra Wusa Nasu Xiang Chinese Chug Nung Wunai Bunu Chocangacakha Dakpakha Khamti Min Bei Chinese Nupbikha Lish Kachari Ta se N a ga Naxi Hmong Njua Brokpake Nisi Khamti Nung Large Flowery Miao Nyenkha Chalikha Sartang Lisu Nung Lisu Southern Pumi Kalaktang Monpa Apatani Khamti Ta se N a ga Wusa Nasu Adap Tshangla Nocte Naga Ayi Nung Khengkha Rawang Gongduk Tshangla Sherdukpen Nocte Naga Lisu Large Flowery Miao Northern Dong Khamti Lipo Wusa NasuWhite Miao Nepali Nepali Lhao Vo Deori Luopohe Miao Ge Southern Pumi White Miao Nepali Konyak Naga Nusu Gelao GelaoNorthern Guiyang MiaoLuopohe Miao Bodo Kachari White Miao Khamti Lipo Lipo Northern Qiandong Miao White Miao Gelao Hmong Njua Eastern Qiandong Miao Phom Naga Khamti Zauzou Lipo Large Flowery Miao Ge Northern Rengma Naga Chang Naga Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Assamese Southern Guiyang Miao Southern Rengma Naga Khamti Ta i N u a Wusa Nasu Northern Huishui