Impact of Catholic Church on Naga Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Summit & Expo

INTERNATIONAL SUMMIT & EXPO 17th to19th January 2020, Maniram Dewan Trade Centre, Guwahati SupporteD By GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM GOVERNMENT OF MIZORAM GOVERNMENT OF TRIPURA MSME EXPORT PROMOTION COUNCIL (Supported by Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India) (Supported by Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India) International Summit & Expo Start & Stand Up North East 17th to 19th January 2020, Guwahati The North East Region undoubtedly is ready to be counted as an equal in the Start Up and Stand Up revolution. The efforts to nurture “Start Ups” and “Stand Ups” ecosystem in the country, by and large, have been limited to the conventionally bigger cities. Whereas most of these products and execution skills need an active support of mentors who can validate assumptions, help them with strategy and provide them with access to relevant networks. The three-day Summit being organized jointly by MSME Export Promotion Bhubaneswar Kalita Bhubaneswar Kalita Council (Supported by Ministry of MSME, Government of India) the Foundation Member of Parliament 2008-2019 for Millennium Sustainable Development Goals and the Confederation of the CHAIRMAN (Hony) Organic Industry of India in Guwahati on 17th to 19th January 2020 shall provide International Summit & Expo Start & Stand Up North East opportunity to connect with the successful and brightest minds to facilitate how to fuel their business growth. The speakers to be drawn from best breed of entrepreneurs, innovators, venture capitalists, consultants, policy makers both from the Centre and States, academicians, business -

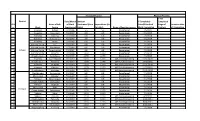

Dated/Month of Work Completion If Not Completed Stage O

Financial Progress Physical Progress If not District Date/Month Amount If Completed- Completed Sl.N Name of Sub- of Work Sanctioned (Rs in Expenditure (Rs. Dated/Month of Stage of Tentative date o Block Centre Sanctionted Lakhs) In Lakhs) Name of Exection agency Work Completion Progress of Completion 1 Viswema Kidima 7/1/2006 5.5 5.5 Department 7/5/2007 2 Viswema Kezo town 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 3 Tseminyu Tsosinyu 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 4 Tseminyu Rhenshenyu 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 5 Viswema Mima 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 6 Kohima Sardar A.G 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 7 Kohima Sardar Kitsubouzu 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 8 Kohima Kohima Sardar Forest colony 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 9 Kohima Sardar Rasoma 7/1/2009 12.33 12.33 Department 7/1/2010 10 Chiephobozou Gariphema 7/1/2009 12.33 12.33 Department 7/1/2010 11 Viswema kijumetouma 6/1/2010 12.33 12.33 M/S Solo Engineering 11/25/2011 12 Chiephobozou Tsiesema 6/1/2010 12.33 12.33 M/S Solo Engineering 10/31/2011 13 Viswema Khuzama 6/1/2010 12.33 12.33 M/S Solo Engineering 11/25/2011 14 Viswema Dihoma 6/1/2010 12.33 12.33 M/S Solo Engineering 11/25/2011 15 Chiephobozou Seiyhama 6/1/2010 12.33 12.33 M/S Solo Engineering 11/25/2011 16 Medziphema Suchonoma 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 17 Dhansiripar Doyapur 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 18 Dimapur Signal Angami 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 19 Chumukedima Diphuphar 7/1/2007 6.8 6.8 Department 7/1/2008 20 Dimapur Lingrijan 7/1/2007 6.8 -

NAGALAND Basic Facts

NAGALAND Basic Facts Nagaland-t2\ Basic Facts _ry20t8 CONTENTS GENERAT INFORMATION: 1. Nagaland Profile 6-7 2. Distribution of Population, Sex Ratio, Density, Literacy Rate 8 3. Altitudes of important towns/peaks 8-9 4. lmportant festivals and time of celebrations 9 5. Governors of Nagaland 10 5. Chief Ministers of Nagaland 10-11 7. Chief Secretaries of Nagaland II-12 8. General Election/President's Rule 12-13 9. AdministrativeHeadquartersinNagaland 13-18 10. f mportant routes with distance 18-24 DEPARTMENTS: 1. Agriculture 25-32 2. Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services 32-35 3. Art & Culture 35-38 4. Border Afrairs 39-40 5. Cooperation 40-45 6. Department of Under Developed Areas (DUDA) 45-48 7. Economics & Statistics 49-52 8. Electricallnspectorate 52-53 9. Employment, Skill Development & Entrepren€urship 53-59 10. Environment, Forests & Climate Change 59-57 11. Evalua6on 67 t2. Excise & Prohibition 67-70 13. Finance 70-75 a. Taxes b, Treasuries & Accounts c. Nagaland State Lotteries 3 14. Fisheries 75-79 15. Food & Civil Supplies 79-81 16. Geology & Mining 81-85 17. Health & Family Welfare 85-98 18. Higher & Technical Education 98-106 19. Home 106-117 a, Departments under Commissioner, Nagaland. - District Administration - Village Guards Organisation - Civil Administration Works Division (CAWO) b. Civil Defence & Home Guards c. Fire & Emergency Services c. Nagaland State Disaster Management Authority d. Nagaland State Guest Houses. e. Narcotics f. Police g. Printing & Stationery h. Prisons i. Relief & Rehabilitation j. Sainik Welfare & Resettlement 20. Horticulture tl7-120 21. lndustries & Commerce 120-125 22. lnformation & Public Relations 125-127 23. -

2001 Asia Harvest Newsletters

Asia Harvest Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe! (Joel 3:13) Box 17 - Chang Klan P.O. - Chiang Mai 50101 - THAILAND Tel: (66-53) 801-487 Fax: (66-53) 800-665 Email: [email protected] Web: www.antioch.com.sg/mission/asianmo April 2001 - Newsletter #61 China’s Neglected Minorities Asia Harvest 2 May 2001 FrFromom thethe FrFrontont LinesLines with Paul and Joy In the last issue of our newsletter we introduced you to our new name, Asia Harvest. This issue we introduce you to our new style of newsletter. We believe a large part of our ministry is to profile and present unreached people groups to Christians around the world. Thanks to the Lord, we have seen and heard of thousands of Christians praying for these needy groups, and efforts have been made by many ministries to take the Gospel to those who have never heard it before. Often we handed to our printer excellent and visually powerful color pictures of minority people, only to be disappointed when the completed newsletter came back in black and white, losing the impact it had in color. A few months ago we asked our printer, just out of curiosity, how much more it would cost if our newsletter was all in full color. We were shocked to find the differences were minimal! In fact, it costs just a few cents more to print in color than in black and white! For this reason we plan to produce our newsletters in color. Hopefully the visual difference will help generate even more prayer and interest in the unreached peoples of Asia! Please look through the pictures in this issue and see the differ- ence color makes. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

A Survey of Baptist World Alliance Conversations with Other Churches

BAPTIST WORLD ALLIANCE Joint meeting of Baptist Heritage and Identity Commission and the Doctrine and Interchurch Cooperation Commission, Seville, 11 July, 2002. A Survey of Baptist World Alliance Conversations with other [1] Churches and some implications for Baptist Identity. (Ken Manley) The Baptist World Alliance has now completed four inter-church conversations. The first was with the World Alliance of Reformed Churches (1973-77); the second with Roman Catholics through the Vatican Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity (1984-88); the third with the Lutheran World Federation (1986-89); the fourth with the Mennonite World Conference (1989- 92).[2] Since then conversations have been held with the Orthodox Church or, more precisely, ‘pre-conversations’ have been shared with the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul (1994-97) although these seem to have been discontinued by the Orthodox representatives. Although initial conversations with the Anglican Consultative Council were commenced in 1991, formal conversations did not begin until 2000 (because of delays by the Anglicans) and are continuing. The question of further talks with the Roman Catholics is being considered. The General Secretary has also raised the desirability of conversations with Pentecostals, a possibility often canvassed also within the Doctrine and Interchurch Cooperation Study Commission.[3] As we prepare to celebrate the centenary of the BWA it is opportune to review these bilateral conversations, assess what has been achieved, acknowledge what has not been accomplished, explore what these conversations have revealed about Baptist identity, both to others and ourselves, and consider future possibilities and directions. The first striking fact about these conversations is that they did not begin until the 1970s! To understand this it is necessary first to consider the larger question of the relationship between the BWA and the ecumenical movement generally. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : NAGALAND DISTRICT : Dimapur Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 STATE CATTLE BREEDING FARM MEDZIPHEMA TOWN DISTRICT DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797106, STD CODE: 03862, 1965 10 - 50 TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0122-Other animal farming; production of animal products n.e.c. 2 STATE CHICK REPARING CENTRE MEDZIPHEMA TOWN DISTRICT DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797106, STD CODE: 03862, TEL 1965 10 - 50 NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 3610-Manufacture of furniture 3 MS MACHANIDED WOODEN FURNITURE DELAI ROAD NEW INDUSTRIAL ESTATE DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD 1998 10 - 50 UNIT CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 4 FURNITURE HOUSE LEMSENBA AO VILLAGE KASHIRAM AO SECTOR DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: 2002 10 - 50 NA , TEL NO: 332936, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 5220-Retail sale of food, beverages and tobacco in specialized stores 5 VEGETABLE SHED PIPHEMA STATION DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA 10 - 50 NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 5239-Other retail sale in specialized stores 6 NAGALAND PLASTIC PRODUCT INDUSTRIAL ESTATE OLD COMPLEX DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: NA , 1983 10 - 50 TEL NO: 226195, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. -

A Publication of the Catholic Archdiocese of Johannesburg Youth News

newsnewsA publication of the Catholic Archdiocese of Johannesburg Youth News Radio Veritas5 SEASON V Year of Family4 Upgrade ADAD Telephone (011) 402 6400 • www.catholicjhb.org.za 66JULY&&77 2014 5 Our very own HOW, WHERE & WHAT • Have you ever wanted to get involved in Catholic Media? Catholic Media Expo • Have you ever wanted to develop your communications skills? media at universities, colleges • Do you want to learn how and schools, grade 11 and 12 stu- to improve your parish dents, and anyone who wants to communications? Raymond improve their skills in this area. Then come to the first ever Catholic Perrier Perrier said all parishes should Cardinal Wilifrid Napier at Media Expo. 25 leading figures from Mater Dolorosa in Kensington be encouraged to participate and the world of Catholic media will be learn to how to communicate present to share their knowledge effectively and to “put their par- and experience and give you a Mass is not about exciting ish on a map.” chance to try different types of Parishioners are encouraged communication. sermons – Napier to bring along their bulletins to • In the morning, you can choose n exciting, innovative learn how to improve on them. to attend up to 4 short sessions to roblems of this world are go and pray, and he included Catholic Media Expo is The day will not be a once-off, give you an idea of different areas only solved if you begin himself in those prayers. He to be held in Johannes- but participants will be encour- • In the afternoon, you can select with yourself. -

Okf"Kzd Izfrosnu Annual Report 2010-11

Annual Report 2010-11 Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya 1 bfUnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky; Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya okf"kZd izfrosnu Annual Report 2010-11 fo'o i;kZoj.k fnol ij lqJh lqtkrk egkik=k }kjk vksfM+lh u`R; dh izLrqfrA Presentation of Oddissi dance by Ms. Sujata Mahapatra on World Environment Day. 2 bfUnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky; okf"kZd izfrosnu 2010&11 Annual Report 2010-11 Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya 3 lwph @ Index fo"k; i`"B dz- Contents Page No. lkekU; ifjp; 05 General Introduction okf"kZd izfrosnu 2010-11 Annual Report 2010-11 laxzgky; xfrfof/k;kWa 06 Museum Activities © bafnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky;] 'kkeyk fgYl] Hkksiky&462013 ¼e-iz-½ Hkkjr Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Shamla Hills, Bhopal-462013 (M.P.) India 1- v/kks lajpukRed fodkl % ¼laxzgky; ladqy dk fodkl½ 07 jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky; lfefr Infrastructure development: (Development of Museum Complex) ¼lkslk;Vh jftLVªs'ku ,DV XXI of 1860 ds varxZr iathd`r½ Exhibitions 07 ds fy, 1-1 izn'kZfu;kWa @ funs'kd] bafnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky;] 10 'kkeyk fgYl] Hkksiky }kjk izdkf'kr 1-2- vkdkZboy L=ksrksa esa vfHko`f) @ Strengthening of archival resources Published by Director, Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Shamla Hills, Bhopal for Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya Samiti (Registered under Society Registration Act XXI of 1860) 2- 'kS{kf.kd ,oa vkmVjhp xfrfof/k;kaW@ 11 fu%'kqYd forj.k ds fy, Education & Outreach Activities For Free Distribution 2-1 ^djks vkSj lh[kks* laxzgky; 'kS{kf.kd dk;Zdze @ -

The Baptist Ministers' Journal

July 2014 volume 323 Desert island books Carol Murray Future ministry John Rackley Pioneers Kathleen Labedz Church and ministry Pat Goodland Community of grace ’ Phil Jump Real marriage Keith John 100 years ago Peter Shepherd journal the baptist ministers baptist the 1 2 the baptist ministers’ journal July 2014, vol 323, ISSN 0968-2406 Contents Desert island books 3 Ministry for the future 6 Ordaining pioneers 9 The church and its ministry 12 A community of grace 18 Real marriage? 22 One hundred years ago 27 Reviews 32 Of interest to you 37 the baptist ministers’ journal© is the journal of the Baptist Ministers’ Fellowship useful contact details are listed inside the front and back covers (all service to the Fellowship is honorary) www.bmf-uk.org The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or the editorial board. Copyright of individual articles normally rests with the author(s). Any request to reproduce an article will be referred to the author(s). We expect bmj to be acknowledged when an article is reproduced. printed by Keenan Print ([email protected]) 3 From the editor The big debate Ministry issues are currently running high on the agenda as the Baptist world morphs into something new. What will we be doing in the future? How will new ministers be formed? Will paid ministry be a thing of the past? BMF has started to hold ’Conversation days’ on topical issues for ministers. Last year’s Conversation (held in London and Sheffield) covered the new marriage laws. -

In One Sacred Effort – Elements of an American Baptist Missiology

In One Sacred Effort Elements of an American Baptist Missiology by Reid S. Trulson © Reid S. Trulson Revised February, 2017 1 American Baptist International Ministries was formed over two centuries ago by Baptists in the United States who believed that God was calling them to work together “in one sacred effort” to make disciples of all nations. Organized in 1814, it is the oldest Baptist international mission agency in North America and the second oldest in the world, following the Baptist Missionary Society formed in England in 1792 to send William and Dorothy Carey to India. International Ministries currently serves more than 1,800 short- term and long-term missionaries annually, bringing U.S. and Puerto Rico churches together with partners in 74 countries in ministries that tell the good news of Jesus Christ while meeting human needs. This is a review of the missiology exemplified by American Baptist International Ministries that has both emerged from and helped to shape American Baptist life. 2 American Baptists are better understood as a movement than an institution. Whether religious or secular, movements tend to be diverse, multi-directional and innovative. To retain their character and remain true to their core purpose beyond their first generation, movements must be able to do two seemingly opposite things. They must adopt dependable procedures while adapting to changing contexts. If they lose the balance between organization and innovation, most movements tend to become rigidly institutionalized or to break apart. Baptists have experienced both. For four centuries the American Baptist movement has borne its witness within the mosaic of Christianity. -

The Naga Conflict

B7-2012 NIAS Backgrounder M Amarjeet Singh THE NAGA CONFLICT NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES Bangalore, India BACKGROUNDERS ON CONFLICT RESOLUTION Series editor: Narendar Pani This series of backgrounders hopes to provide accessible and authentic overviews of specific conflicts that affect India, or have the potential to do so. It is a part of a larger effort by the Conflict Resolution Programme at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore, to develop an inclusive knowledge base that would help effectively address major conflicts of interest to the country. In pursuit of this objective it carries out research that could help throw up fresh perspectives on conflict even as it develops mechanisms to increase awareness about the nature of specific crises.The backgrounders form an important part of the second exercise. The backgrounders are targeted at the intelligent layperson who requires a quick and yet reliable account of a specific conflict.These introductory overviews would be useful to administrators, media personnel and others seeking their first information on a particular conflict. It is also hoped that as the series grows it will act as an effective summary of scholarly information available on conflicts across the country. By their very nature these backgrounders attempt to provide a picture on which there is some measure of consensus among scholars. But we are quite aware that this is not always possible.The views expressed are those of the author(s); and not necessarily those of the National Institute of Advanced Studies.The dissemination of these backgrounders to all who may need them is an important part of the entire effort.