Intelligence Tests Notebook Page 19 Intelligence Tests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herrmann Collection Books Pertaining to Human Memory

Special Collections Department Cunningham Memorial Library Indiana State University September 28, 2010 Herrmann Collection Books Pertaining to Human Memory Gift 1 (10/30/01), Gift 2 (11/20/01), Gift 3 (07/02/02) Gift 4 (10/21/02), Gift 5 (01/28/03), Gift 6 (04/22/03) Gift 7 (06/27/03), Gift 8 (09/22/03), Gift 9 (12/03/03) Gift 10 (02/20/04), Gift 11 (04/29/04), Gift 12 (07/23/04) Gift 13 (09/15/10) 968 Titles Abercrombie, John. Inquiries Concerning the Intellectual Powers and the Investigation of Truth. Ed. Jacob Abbott. Revised ed. New York: Collins & Brother, c1833. Gift #9. ---. Inquiries Concerning the Intellectual Powers, and the Investigation of Truth. Harper's Stereotype ed., from the second Edinburgh ed. New York: J. & J. Harper, 1832. Gift #8. ---. Inquiries Concerning the Intellectual Powers, and the Investigation of Truth. Boston: John Allen & Co.; Philadelphia: Alexander Tower, 1835. Gift #6. ---. The Philosophy of the Moral Feelings. Boston: Otis, Broaders, and Company, 1848. Gift #8. Abraham, Wickliffe, C., Michael Corballis, and K. Geoffrey White, eds. Memory Mechanisms: A Tribute to G. V. Goddard. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1991. Gift #9. Adams, Grace. Psychology: Science or Superstition? New York: Covici Friede, 1931. Gift #8. Adams, Jack A. Human Memory. McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, c1967. Gift #11. ---. Learning and Memory: An Introduction. Homewood, Illinois: The Dorsey Press, 1976. Gift #9. Adams, John. The Herbartian Psychology Applied to Education Being a Series of Essays Applying the Psychology of Johann Friederich Herbart. -

CUA V04 1913 14 16.Pdf (6.493Mb)

T OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS OF CORNELL UNIVERSITY VOLUME IV NUMBER 16 CATALOGUE NUMBER 1912-13 AUGUST I. 1913 PUBLISHED BY CORNELL UNIVERSITY ITHACA. NEW YORK — . r, OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS OF CORNELL UNIVERSITY VOLUME IV NUMBER 16 CATALOGUE NUMBER 1912-13 AUGUST 1, 1913 PUBLISHED BY CORNELL UNIVERSITY ITHACA, NEW YORK CALENDAR First Term, 1913-14 Sept. 12, Friday, Entrance examinations begin. Sept. 22, Monday, Academic year begins. Registration of new students. Scholarship examinations begin. Sept. 23, Tuesday, Registration of new students. Registration in the Medical College in N. Y. City. Sept. 24, Wednesday, Registration of old students. Sept. 25, Thursday, Instruction begins in all departments of the University at Ithaca. President’s annual address to the students at 12 m. Sept. 27, Saturday, Registration, Graduate School. Oct. 14, Tuesday, Last day for payment of tuition. Nov. 11, Tuesday, Winter Courses in Agriculture begin. Nov. — , Thursday and Friday, Thanksgiving Recess. Dec. 1, Monday, Latest date for announcing subjects of theses for advanced degrees. Dec. 20, Saturday, Instruction ends 1 ™ ■ , Jan. 5, Monday, Instruction resumed [Christmas Recess. Jan. 10, Saturday, The ’94 Memorial Prize Competition. Jan. 11, Sunday, Founder’s Day. Jan. 24, Saturday, Instruction ends. Jan. 26, Monday, Term examinations begin. Second Term, 1913-14 Feb. 7, Saturday, Registration, undergraduates. Feb. 9, Monday, Registration, Graduate School. Feb. 9, Monday, Instruction begins. Feb. 13, Friday, Winter Courses in Agriculture end. Feb. 27, Friday, Last day for payment of tuition. Mar. 16, Monclay, The latest date for receiving applications for Fellowships and Scholarships in the Gradu ate School. April 1, Wednesday, Instruction ends T o - April 9, Thursday, Instruction resumed ) Spring Recess. -

Techofworld.In

Techofworld.In YouTube Mock Test Previous Year PDF Best Exam Books Check Here Check Here Check Here Check Here Previous Year CT & B.Ed Cut Off Marks (2019) Items CT Entrance B.Ed Arts B.Ed Science Cut Off Check Now Check Now Check Now Best Book For CT & B.Ed Entrance 2020 Items CT Entrance B.Ed Arts B.Ed Science Book (Amazon) Check Now Check Now Check Now Mock Test Related Important Links- Mock Test Features (Video) Watch Now Watch Now How To Register For Mock Test (Video) Watch Now Watch Now How To Give Mock (Video) Watch Now Watch Now P a g e | 1 Click Here- Online Test Series For CT, B.Ed, OTET, Railway, Odisha Police, OSSSC, B.Ed Arts (2018 & 2019) Teaching Aptitude Total Shifts – 13 ( By Techofworld.In ) 8596976190 P a g e | 2 Click Here- Online Test Series For CT, B.Ed, OTET, Railway, Odisha Police, OSSSC, 03-June-2019_Batch1 B) Project method 21) One of the five components of the centrally C) Problem solving method sponsored Scheme of Restructuring and D) Discussion method Reorganization of Teacher Education under the Government of India was establishment of DIETs. What is the full form of DIET? 25) Focus of the examination on rank ordering A) Dunce Institute of Educational Training students or declaring them failed tilts the classroom climate and the school ethos towards B) Deemed Institute of Educational Training A) vicious competition C) District Institute of Educational Training B) passive competition D) Distance Institute of Educational Training C) healthy competition D) joyful competition 22) One of the maxims of teaching -

Behavioral Finance Micro 19 CHAPTER 3 Incorporating Investor Behavior Into the Asset Allocation Process 39

00_POMPIAN_i_xviii 2/7/06 1:58 PM Page iii Behavioral Finance and Wealth Management How to Build Optimal Portfolios That Account for Investor Biases MICHAEL M. POMPIAN John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 00_POMPIAN_i_xviii 2/7/06 1:58 PM Page vi 00_POMPIAN_i_xviii 2/7/06 1:58 PM Page i Behavioral Finance and Wealth Management 00_POMPIAN_i_xviii 2/7/06 1:58 PM Page ii Founded in 1807, John Wiley & Sons is the oldest independent publish- ing company in the United States. With offices in North America, Europe, Australia, and Asia, Wiley is globally committed to developing and marketing print and electronic products and services for our cus- tomers’ professional and personal knowledge and understanding. The Wiley Finance series contains books written specifically for fi- nance and investment professionals as well as sophisticated individual in- vestors and their financial advisors. Book topics range from portfolio management to e-commerce, risk management, financial engineering, valuation, and financial instrument analysis, as well as much more. For a list of available titles, please visit our web site at www.Wiley Finance.com. 00_POMPIAN_i_xviii 2/7/06 1:58 PM Page iii Behavioral Finance and Wealth Management How to Build Optimal Portfolios That Account for Investor Biases MICHAEL M. POMPIAN John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 00_POMPIAN_i_xviii 2/7/06 1:58 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Michael M. Pompian. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior writ- ten permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the ap- propriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. -

Teaching Guide for the History of Psychology Instructor Compiled by Jennifer Bazar, Elissa Rodkey, and Jacy Young

A Teaching Guide for History of Psychology www.feministvoices.com 1 Psychology’s Feminist Voices in the Classroom A Teaching Guide for the History of Psychology Instructor Compiled by Jennifer Bazar, Elissa Rodkey, and Jacy Young One of the goals of Psychology’s Feminist Voices is to serve as a teaching resource. To facilitate the process of incorporating PFV into the History of Psychology course, we have created this document. Below you will find two primary sections: (1) Lectures and (2) Assignments. (1) Lectures: In this section you will find subject headings of topics often covered in History of Psychology courses. Under each heading, we have provided an example of the relevant career, research, and/or life experiences of a woman featured on the Psychology’s Feminist Voices site that would augment a lecture on that particular topic. Below this description is a list of additional women whose histories would be well-suited to lectures on that topic. (2) Assignments: In this section you will find several suggestions for assignments that draw on the material and content available on Psychology’s Feminist Voices that you can use in your History of Psychology course. The material in this guide is intended only as a suggestion and should not be read as a “complete” list of all the ways Psychology’s Feminist Voices could be used in your courses. We would love to hear all of the different ideas you think of for how to include the site in your classroom - please share you thoughts with us by emailing Alexandra Rutherford, our project coordinator, -

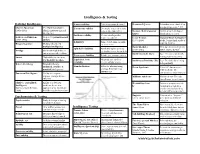

Intelligence & Testing

Intelligence & Testing Defining Intelligence Content validity Is the test comprehensive? Deviation IQ score Individual score divided by averge group score * 100 Charles Spearman Used factor analysis to Concurrent validity Do results match other tests (1863-1945) identify g-factor (general done at the same time? Normal / Bell / Gaussian Symmetrical bell-shaped intelligence) Curve distribution of scores Predictive validity Do test results predict Louis Leon Thurstone Proposed 7 primary mental future outcomes? Lewis Terman Stanford-Binet Intelligence (1887-1955) abilities (1877-1956) Scale; longitudinal study of Reliability Same object, same measure high IQ children Howard Gardner Modular theory of 8 → same score multiple intelligences David Wechsler Developed several IQ tests; Split-half reliability Randomly split test items (1896-1981) WAIS, WISC, WPPSI Prodigy Child with high ability in → similar scores for each ½ one area; normal in others Intellectual Giftedness IQ ≥ 130; associated with Test-retest reliability Retake test; compare scores Savant High ability in one area; many positive outcomes low/disability in others Equivalent form Alternate test versions Intellectual Disability (ID) IQ ≤ 70; difficulties living reliability receive similar scores Robert Sternberg Triarchic theory: independently analytical, creative, & Standardization Rules for administering, Down Syndrome Extra 21st chromosome; practical intelligences scoring, & interpreting mild/moderate ID, (norms) test Emotional Intelligence Ability to recognize, characteristic -

Inventing Intelligence: on the History of Complex Information Processing and Artificial Intelligence in the United States in the Mid-Twentieth Century

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Inventing Intelligence: On the History of Complex Information Processing and Artificial Intelligence in the United States in the Mid-Twentieth Century This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History and Philosophy of Science By Jonathan Nigel Ross Penn (‘Jonnie Penn’) Pembroke College, Cambridge Examiners: Professor Simon Schaffer, University of Cambridge Professor Jon Agar, University College London Supervisor: Dr. Richard Staley, University of Cambridge Advisor: Dr. Helen Anne Curry, University of Cambridge Word Count: 78,033 Date: 14 December 2020 This thesis is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my thesis has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the Degree Committee of the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge. Copyright Jonnie Penn, 2020. All rights reserved. 2 Abstract Inventing Intelligence: On the History of Complex Information Processing and Artificial Intelligence in the United States in the Mid-Twentieth Century In the mid-1950s, researchers in the United States melded formal theories of problem solving and intelligence with another powerful new tool for control: the electronic digital computer. -

Personal Politics: the Rise of Personality Traits in The

PERSONAL POLITICS: THE RISE OF PERSONALITY TRAITS IN THE CENTURY OF EUGENICS AND PSYCHOANALYSIS IAN J. DAVIDSON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN PSYCHOLOGY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO AUGUST 2020 © IAN J. DAVIDSON, 2020 ii Abstract This dissertation documents personality psychology’s development alongside psychoanalysis and eugenics, offering a disciplinary and cultural history of personality across the twentieth century. Using the psychological concepts of neurosis and introversion as an organizational framework, personality’s history is portrayed as one of “success:” a succession of hereditarianism and its politics of normativity; a successful demarcation of the science of personality from competing forms of expertise; and a successful cleansing of personality psychology’s interchanges with unethical researchers and research. Chapter 1 provides background for the dissertation, especially focusing on turn-of-the- century developments in the nascent fields of American psychology and the importation of psychoanalytic ideas. It ends with a look at Francis Galton’s eugenicist and statistical contributions that carved a key path for psychological testers to discipline psychoanalytic concepts. Part I details the rise of personality testing in the USA during the interwar years, while also considering the many sexual and gender norms at play. Chapter 2 tracks the varied places in the 1920s that personality tests were developed: from wartime military camps to university laboratories to the offices of corporate advertisers. Chapter 3 takes stock of popular psychoanalytic notions of personality alongside the further psychometric development of personality testing. These developments occurred at a time when American eugenicists— including psychologists—were transitioning to a “positive” form that emphasized marriage and mothering. -

Lewis Madison Terman

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES L E W IS MADISON T ERMAN 1877—1956 A Biographical Memoir by E D WI N G . B O R I N G Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1959 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. LEWIS MADISON TERMAN January 15, i8jj-December 21, 1956 BY EDWIN G. BORING EWIS MADISON TERMAN, for fifty years one of America's staunchest I-J supporters of mental testing as a scientific psychological tech- nique, and for forty years the psychologist who more than any other was responsible for making the IQ (the intelligence quotient) a household word, was born on a farm in Johnson County, Indiana, on January 15, 1877, and died at Stanford University on Decem- ber 21, 1956, a distinguished professor emeritus, not quite eighty years old.1 When a biographer seeks to find causes for the events in the life that he is describing, he is apt to find himself facing the nature-nur- ture dilemma, uncertain whether, in order to account for the traits of his subject, he should look to ancestry or to environment. Ter- man, as it happens—when he wrote his own biography at the age of fifty-five (1932)—faced exactly this problem in accounting for him- self.2 In his choices he must indeed have been influenced by the Zeitgeist, for, as the weight of scientific opinion shifted from heredi- tarianism toward environmentalism, his judgment shifted too throughout the forty years (1916-1956) during which this issue re- mained vital to him. -

Research Proposal Was Approved by Human Subjects, the Entire Group Of

IMPACT OF CULTURAL INTELLIGENCE ON THE LEADERSHIP PRACTICES OF ELEMENTARY PRINCIPALS Linda Davis Meyerson B.A., Texas Wesleyan University, Fort Worth, Texas, 1972 M.A., California State University, Fresno, 1996 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION in EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2012 Copyright © 2012 Linda Davis Meyerson All rights reserved ii IMPACT OF CULTURAL INTELLIGENCE ON THE LEADERSHIP PRACTICES OF ELEMENTARY PRINCIPALS A Dissertation by Linda Davis Meyerson Approved by Dissertation Committee: Frank Lilly, Ph.D., Chair Edmund W. Lee, Ed.D. Jana Noel, Ph.D. SPRING 2012 iii IMPACT OF CULTURAL INTELLIGENCE ON THE LEADERSHIP PRACTICES OF ELEMENTARY PRINCIPALS Student: Linda Davis Meyerson I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this dissertation is suitable for shelving in the library and credit is to be awarded for the dissertation. , Department Chair Caroline S. Turner, Ph.D./Professor Date iv DEDICATION This study is dedicated to my Mom and Dad who felt my brother and me were their most prized possessions. Their work ethic and determination to overcome the challenges life offered set the example for me to know that all things are possible with dedication, determination, pride and hard work. This study is also dedicated to Jonathan and Matthew Meyerson. My hope is that I have effectively modeled the importance of education, diligence, and the attainment of personal goals. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study could not be completed without the support from those who inspired me to continue with my dreams even when times were difficult. -

A Brief Review of the History and Philosophy of Instrument Development in the Social Sciences

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 8 , No. 9, Sept. 2018, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2018 HRMARS A Brief Review of the History and Philosophy of Instrument Development in the Social Sciences Khairun Nisa Khairuddin, Zoharah Omar, Steven Eric Krauss, Ismi Arif Ismail To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i9/4861 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i9/4861 Received: 19 August 2018, Revised: 09 Sept 2018, Accepted: 29 Sept 2018 Published Online: 19 October 2018 In-Text Citation: (Khairuddin, Omar, Krauss, & Ismail, 2018) To Cite this Article: Khairuddin, K. N., Omar, Z., Krauss, S. E., & Ismail, I. A. (2018). A Brief Review of the History and Philosophy of Instrument Development in the Social Sciences. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(9), 1517–1524. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 8, No. 9, September 2018, Pg. 1517 - 1524 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 1517 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

Outline of Human Intelligence

Outline of human intelligence The following outline is provided as an overview of and 2 Emergence and evolution topical guide to human intelligence: Human intelligence – in the human species, the mental • Noogenesis capacities to learn, understand, and reason, including the capacities to comprehend ideas, plan, problem solve, and use language to communicate. 3 Augmented with technology • Humanistic intelligence 1 Traits and aspects 1.1 In groups 4 Capacities • Collective intelligence Main article: Outline of thought • Group intelligence Cognition and mental processing 1.2 In individuals • Association • Abstract thought • Attention • Creativity • Belief • Emotional intelligence • Concept formation • Fluid and crystallized intelligence • Conception • Knowledge • Creativity • Learning • Emotion • Malleability of intelligence • Language • Memory • • Working memory Imagination • Moral intelligence • Intellectual giftedness • Problem solving • Introspection • Reaction time • Memory • Reasoning • Metamemory • Risk intelligence • Pattern recognition • Social intelligence • Metacognition • Communication • Mental imagery • Spatial intelligence • Perception • Spiritual intelligence • Reasoning • Understanding • Abductive reasoning • Verbal intelligence • Deductive reasoning • Visual processing • Inductive reasoning 1 2 8 FIELDS THAT STUDY HUMAN INTELLIGENCE • Volition 8 Fields that study human intelli- • Action gence • Problem solving • Cognitive epidemiology • Evolution of human intelligence 5 Types of people, by intelligence • Heritability of