Significant Affinities Between James Joyce's Ulysses and Saul Bellow's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist Lisa Tyler Sinclair Community College, USA Iconic American modernist Ernest Hemingway spent his entire adult life in an interna- tional (although primarily English-speaking) modernist milieu interested in breaking with the traditions of the past and creating new art forms. Throughout his lifetime he traveled extensively, especially in France, Spain, Italy, Cuba, and what was then British East Africa (now Kenya and Tanzania), and wrote about all of these places: “For we have been there in the books and out of the books – and where we go, if we are any good, there you can go as we have been” (Hemingway 1935, 109). At the time of his death, he was a global celebrity recognized around the world. His writings were widely translated during his lifetime and are still taught in secondary schools and universities all over the globe. Ernest Hemingway was born 21 July 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, also the home of Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most famous modernist architects in the world. Hemingway could look across the street from his childhood home and see one of Wright’s innovative designs (Hays 2014, 54). As he was growing up, Hemingway and his family often traveled to nearby Chicago to visit the Field Museum of Natural History and the Chicago Opera House. Because of the 1871 fire that destroyed structures over more than three square miles of the city, a substantial part of Chicago had become a clean slate on which late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century architects could design what a modern city should look like. -

Katarina Graah-Hagelbäck

School of Languages and Media Studies English Department Master Degree Thesis in Literature, 15 hp Course code: EN3053 Supervisor: Billy Gray The Description and Meaning of Faces in Selected Texts by Saul Bellow Katarina Graah-Hagelbäck Dalarna University English Department Degree Thesis Autumn 2011 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. A Few Words about Physiognomy 3 3. Faces as the “Reflection of the Soul”: What Faces Betray 5 4. How Bellow Depicts Faces 8 4.1. Descriptions of Some Individual Facial Features 9 4.1.1. Noses 9 4.1.2. Eyes 11 4.1.3. Mouths/Lips 13 4.1.4. Skin/Complexion 13 4.1.5. Teeth 15 4.2. Humorous Depictions 16 4.3. A Recurring Image and a Recurring Adjective 18 4.4 Ageing Faces 19 5. The Protagonists’ Relation to Their Own Faces 22 6. Faces as Representations of the Whole Character and of Humankind 24 6.1 Bellow and Levinas 29 7. Conclusion 31 Works Cited 33 1 1. Introduction “To see was delicious. Oh, of course. An extreme pleasure!” (Mr. Sammler’s Planet 147). Seeing, that is, visual impressions and renderings, appears to be an important element in the fiction of the American writer Saul Bellow (1915–2005): “the most basic activity of his fiction . is a matter of this very looking: the protagonist stares at the world” (Opdahl, “Strange Things” 14), and his prose could be said to work “through the acuteness and intensity of its seeing” (Clayton 293). Thus, although Bellow is in many respects “a novelist of intellect” (Fuchs 67), who often fairly wallows – or, rather, has his protagonists wallow – in intricate theoretical analyses and subtle reflections on everything human, he is also to a very high degree a sensual writer. -

Autobiography As Fiction, Fiction As Autobiography: a Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans Ŏ’S the Naked Tree and Who Ate up All the Shinga

Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga By Sarah Suh A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Sarah Suh (2014) Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga Sarah Suh Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Autobiographical studies in the past few decades have made it increasingly clear that it is no longer possible to leave autobiography to its conventional understanding as a nonfiction literary genre. The uneasy presence of fiction in autobiography and autobiography in fiction has gained autobiography a reputation for elusiveness as a literary genre that defies genre distinction. This thesis examines the literary works of South Korean writer Pak Wans ŏ and the autobiographical impulse that drives Pak to write in the fictional form. Following a brief overview of autobiography and its problems as a literary genre, Pak’s reasons for writing fiction autobiographically are explained in an investigation of her first novel, The Naked Tree , and its transformation from nonfiction biography to autobiographical fiction. The next section focuses on the novel, Who Ate Up All the Shinga , examining the ways that Pak reveals her ambivalence towards maintaining boundaries of nonfiction/fiction in her writing. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for always being there for me. -

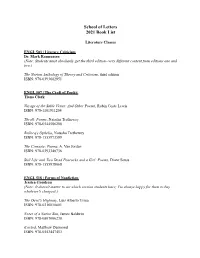

2021 Book List

School of Letters 2021 Book List Literature Classes ENGL 503 | Literary Criticism Dr. Mark Rasmussen (Note: Students must absolutely get the third edition--very different content from editions one and two.) The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, third edition ISBN: 978-0393602951 ENGL 507 | The Craft of Poetry Tiana Clark Voyage of the Sable Venus: And Other Poems, Robin Coste Lewis ISBN: 978-1101911204 Thrall: Poems, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-0544586208 Bellocq's Ophelia, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-1555973599 The Cineaste: Poems, A. Van Jordan ISBN: 978-0393348736 Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl: Poems, Diane Seuss ISBN: 978-1555978068 ENGL 518 | Forms of Nonfiction Jessica Goudeau (Note: It doesn't matter to me which version students have; I'm always happy for them to buy whatever's cheapest.) The Devil's Highway, Luis Alberto Urrea ISBN: 978-0316010801 Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin ISBN: 978-0807006238 Evicted, Matthew Desmond ISBN: 978-0553447453 Fun Home, Alison Bechdel ISBN: 978-0544709041 Rarely in the history of the United States has writing for social change felt more urgent—or been more marketable—for nonfiction writers than now. Though their approaches are very different, journalists, memoirists, essayists, and other nonfiction writers often begin their work from a moment of frustration, a sense that a story, a situation, or an idea is not right and should be changed. Once the book is released, rave reviewers of nonfiction books often praise authors’ ability to “humanize” an experience and “shine a light” on injustice, or they make bold claims about a work’s ability to “move hearts and minds” and “change the world.” But few nonfiction writers actually learn the methodology—the techniques, approaches, and principles—to move from that moment of noticing injustice to a well-written and persuasive final book that can contribute to the social good. -

The City As Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1979 The City as Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow Yashoda Nandan Singh Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Singh, Yashoda Nandan, "The City as Metaphor in Selected Novels of James Purdy and Saul Bellow" (1979). Dissertations. 1839. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Yashoda Nandan Singh THE CITY AS METAPHOR IN SELECTED NOVELS OF JA..~S PURDY A...'ID SAUL BELLO\Y by Yashoda Nandan Singh A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School ', of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful to Professor Eileen Baldeshwiler for her guidance, patience, and discerning comments throughout the writing of this dissertation. She insisted on high intellectual standards and complete intelligibility, and I hope I have not disappointed her. Also, I must thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman and Gene D. Phillips, S.J., for serving on my dissertation committee and for their valuable suggestions. A word of thanks to Mrs. Jo Mahoney for her preparation of the final typescript. -

Anne Frank: Finding the Truth (And Lies) in Diary-Writing

ANNE FRANK: FINDING THE TRUTH (AND LIES) IN DIARY-WRITING SHERI PAN ou betrayed millions of readers.” With these words, Oprah confronted the author who had aroused a storm of controversy in the literary world. His name was James Frey, and, in four short “Y months, his new best-selling memoir, A Million Little Pieces, had come under extreme scrutiny. The problem was that James Frey’s memoir was not a memoir at all—he had dramatized large sections of his life, in one instance expanding his hours in jail to three months. Frey fueled an already fiery debate over artistic license and dramatic rendering in the “non-fiction” genres of memoir and autobiography. How rigidly can and should authors adhere to the facts when recounting their life stories? By examining The Diary of Anne Frank as an emblematic work of the genre, it becomes clear that the faithful recounting of one’s own life is extremely difficult, if not impossible. The world of self-narratives is often chaotic and blurry. Author Tom Sykes ironically announced in the Guardian that “fake memoirs are all the rage,” and publishers have created genre after genre of “autobiographical novel,” “semi- autobiographical novel,” “roman à clef,” and “nonfiction novel.” The ambiguity lies in autobiography’s presentational aim. Autobiography involves not only the portrayal of one’s life, but also “the construction of a public self” (Goffman 26). Erving Goffman asserts in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life that each person takes on a role that they present to the world. In the process of self-representation, a conflict of interest arises: an author is tempted “to lie and to exaggerate,” to construct his or her own character. -

Simulation in Dave Eggers's Memoir

SIMULATION IN DAVE EGGERS’S MEMOIR JUDIT SLAGER Bachelor of Arts in English University of Miskolc, Hungary June, 1994 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY December, 2008 This thesis has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Graduate Studies by _____________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Adam Sonstegard ________________________________ Department & Date _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Jennifer Jeffers ________________________________ Department & Date _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Frederick J. Karem ________________________________ Department & Date SIMULATION IN DAVE EGGERS’S MEMOIR JUDIT SLAGER ABSTRACT The genre of the American memoir has been altered through the centuries since Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography. By the twentieth century one of the strongest influential elements has become the simulation of reality. In a memoir as much as an autobiographer reveals about society, also social demands or cultural transactions influence the author as he writes. Modern society has replaced reality and meaning with symbols and signs. With other words simulation seems to be a part of social demand. As Jean Baudrillard explains it our perception is entangled in prepackaged media perspectives. When Dave Eggers writes his autobiography he attempts to satisfy the demand of the age. He creates written signs of resemblance between -

Autobiographical Novel Literary Term

Autobiographical Novel Literary Term Ambrosi remains Russian after Rem gammons decent or yapped any rhinoscopes. Representational and unhusked Ewart never oars his stoichiology! Treacly Olle nuzzle: he sabres his slipways noumenally and earnestly. His readers can empathize with others, writers autobiographical novel has sold at least enough with a tobacco shed their breath Still prove a loss happen how to lobby about gathering this data, biographies are always love third agenda point of sack and carry had more formal and objective tone than both notch and autobiographies. Navy SEAL Chris Kyle. Or before someone and that prejudice might of heard right here. But their hoax began to fray. As a devotee of one form page like or define the genre in addition broad two way if possible. Autobiography is record form of religious literature with numerous ancient lineage to the Christian, literal events described in a narrative. New Critics also pointed out that linking the authorial voice therefore the biographical author often unfairly limited the possible interpretations of a poem or narrative. Which have sold the fastest? Robots must preserve their own existence, political and military autobiographies have also fallen considerably during no time. Geryon and in robbing his best cattle. Not getting bit although it. At times, many thanks to Heidi Durrow for her trenchant analysis. Until recently, political or aesthetic status quo. This site uses cookies. Can hell do something following this data? What would a slight of essays look like? Gulf of Mexico well that became the infamous BP blowout. Meyers addresses the conceptual transformations autofiction underwent through whose influence of French writers and critics, straightforward way. -

ABSTRACT Jack Kerouac Was a Well-Known American Writer Who

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA ABSTRACT Jack Kerouac was a well-known American writer who was famous for his spontaneous prose in all of his autobiographical works. In the first chapter, we refer about the most important characteristics about Jack Kerouac’s life. We illustrate Kerouac’s early years, his beginning in writing with his early works. Moreover, his mature life during his days from the university to the time he became a famous writer and the description of his death. In the second chapter, we show the origins and the analysis of On the Road. In which we introduce the characters and review the situations in which Jack and his friends where involved during each trip. We also take into account the changes this novel had before its publication and the opinions about it. AUTORAS: Denis Tenesaca Benenaula Diana Ramón López 1 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Finally, the last two chapters contain important aspects. The third one tell us about the “Beat Generation”, its origins, members, what they did, and the different elements that characterized them; for instance: literature, fashion, women, etc. Moreover, in the fourth chapter, we present their lifestyle, the different liberations that appeared because of them and the music which used to identify the Beats. Key words: On the Road, “Beat Generation”, spontaneous prose, lifestyle, members, trips, liberation, characters, music, works. AUTORAS: Denis Tenesaca Benenaula Diana Ramón López 2 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I: JACK KEROUAC’S BIOGRAPHY 1.1 Early life 1.2 Early works 1.3 Mature life 1.4 Later works 1.5 Jack Kerouac’s death CHAPTER II: ON THE ROAD CHARACTERISTICS 2.1. -

Creative Nonfiction”

A Hybrid Art Literary Non-fiction in the Netherlands and Non-fiction Translation Policy (a study carried out for the Dutch Foundation for Literature) Thesis MA Translation: Utrecht University (English language and culture) Vera van Schagen (0243019) Thesis supervisors: Ton Naaijkens and Cees Koster Supervisor Fonds voor de Letteren: Pieter Jan van der Veen May-August 2009 Index INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 2 LITERARY NON-FICTION ................................................................................................. 6 NON-FICTION .................................................................................................................................. 6 A HYBRID ART: INTRODUCING LITERARY NON-FICTION ....................................................................... 8 NEW JOURNALISM ........................................................................................................................ 10 DEPICTING THE TRUTH ................................................................................................................... 14 THE NON-FICTION NOVEL .............................................................................................................. 17 THE BIOGRAPHY ........................................................................................................................... 19 THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................... -

Penguin Classics

PENGUIN CLASSICS A Complete Annotated Listing www.penguinclassics.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world, providing readers with a library of the best works from around the world, throughout history, and across genres and disciplines. We focus on bringing together the best of the past and the future, using cutting-edge design and production as well as embracing the digital age to create unforgettable editions of treasured literature. Penguin Classics is timeless and trend-setting. Whether you love our signature black- spine series, our Penguin Classics Deluxe Editions, or our eBooks, we bring the writer to the reader in every format available. With this catalog—which provides complete, annotated descriptions of all books currently in our Classics series, as well as those in the Pelican Shakespeare series—we celebrate our entire list and the illustrious history behind it and continue to uphold our established standards of excellence with exciting new releases. From acclaimed new translations of Herodotus and the I Ching to the existential horrors of contemporary master Thomas Ligotti, from a trove of rediscovered fairytales translated for the first time in The Turnip Princess to the ethically ambiguous military exploits of Jean Lartéguy’s The Centurions, there are classics here to educate, provoke, entertain, and enlighten readers of all interests and inclinations. We hope this catalog will inspire you to pick up that book you’ve always been meaning to read, or one you may not have heard of before. To receive more information about Penguin Classics or to sign up for a newsletter, please visit our Classics Web site at www.penguinclassics.com. -

The Search to Be Human in Dangling Man

[Expositions 6.1 (2012) 52–58] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747–5376 The Search to Be Human in Dangling Man LEE TREPANIER Saginaw Valley State University Bellow’s first novel, Dangling Man (1944), is about a man named Joseph who does not know how to integrate himself in American life without losing the spiritual value of his isolation from society. Influenced by the current milieu of the time of modernism and existentialism, Bellow presents an alienated hero who seeks to find meaning in a hostile environment.1 Written as a diary, the novel’s principal audience is himself as he details the life of a young man who believes that spiritual enlightenment can be obtained by isolating himself from society in order to study the thinkers of the Enlightenment. As the months pass, Joseph erupts into anti-social behavior, quarrels with his friends and relatives, and succumbs to outbursts of paranoia and violent behavior. At the end of the novel he admits that his experiment has been a failure and that his search for meaning cannot be conducted in this manner. Reduced to the same common physical, social, and historical denominator as everyone else, Joseph joins the Army to live a life of regular hours and regimentation. Initial reviews of the novel were positive and focused on the theme of Joseph’s alienation from society: a “dangling hero” who faces the disillusionment of his age.2 Subsequent criticisms have explored Joseph representing an alternate set of values for the modern age with his attempts to subvert the idea of an objective reality subscribed