Anne Frank: Finding the Truth (And Lies) in Diary-Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist Lisa Tyler Sinclair Community College, USA Iconic American modernist Ernest Hemingway spent his entire adult life in an interna- tional (although primarily English-speaking) modernist milieu interested in breaking with the traditions of the past and creating new art forms. Throughout his lifetime he traveled extensively, especially in France, Spain, Italy, Cuba, and what was then British East Africa (now Kenya and Tanzania), and wrote about all of these places: “For we have been there in the books and out of the books – and where we go, if we are any good, there you can go as we have been” (Hemingway 1935, 109). At the time of his death, he was a global celebrity recognized around the world. His writings were widely translated during his lifetime and are still taught in secondary schools and universities all over the globe. Ernest Hemingway was born 21 July 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, also the home of Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most famous modernist architects in the world. Hemingway could look across the street from his childhood home and see one of Wright’s innovative designs (Hays 2014, 54). As he was growing up, Hemingway and his family often traveled to nearby Chicago to visit the Field Museum of Natural History and the Chicago Opera House. Because of the 1871 fire that destroyed structures over more than three square miles of the city, a substantial part of Chicago had become a clean slate on which late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century architects could design what a modern city should look like. -

Autobiography As Fiction, Fiction As Autobiography: a Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans Ŏ’S the Naked Tree and Who Ate up All the Shinga

Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga By Sarah Suh A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Sarah Suh (2014) Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga Sarah Suh Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Autobiographical studies in the past few decades have made it increasingly clear that it is no longer possible to leave autobiography to its conventional understanding as a nonfiction literary genre. The uneasy presence of fiction in autobiography and autobiography in fiction has gained autobiography a reputation for elusiveness as a literary genre that defies genre distinction. This thesis examines the literary works of South Korean writer Pak Wans ŏ and the autobiographical impulse that drives Pak to write in the fictional form. Following a brief overview of autobiography and its problems as a literary genre, Pak’s reasons for writing fiction autobiographically are explained in an investigation of her first novel, The Naked Tree , and its transformation from nonfiction biography to autobiographical fiction. The next section focuses on the novel, Who Ate Up All the Shinga , examining the ways that Pak reveals her ambivalence towards maintaining boundaries of nonfiction/fiction in her writing. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for always being there for me. -

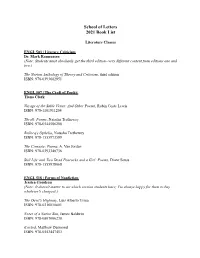

2021 Book List

School of Letters 2021 Book List Literature Classes ENGL 503 | Literary Criticism Dr. Mark Rasmussen (Note: Students must absolutely get the third edition--very different content from editions one and two.) The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, third edition ISBN: 978-0393602951 ENGL 507 | The Craft of Poetry Tiana Clark Voyage of the Sable Venus: And Other Poems, Robin Coste Lewis ISBN: 978-1101911204 Thrall: Poems, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-0544586208 Bellocq's Ophelia, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-1555973599 The Cineaste: Poems, A. Van Jordan ISBN: 978-0393348736 Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl: Poems, Diane Seuss ISBN: 978-1555978068 ENGL 518 | Forms of Nonfiction Jessica Goudeau (Note: It doesn't matter to me which version students have; I'm always happy for them to buy whatever's cheapest.) The Devil's Highway, Luis Alberto Urrea ISBN: 978-0316010801 Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin ISBN: 978-0807006238 Evicted, Matthew Desmond ISBN: 978-0553447453 Fun Home, Alison Bechdel ISBN: 978-0544709041 Rarely in the history of the United States has writing for social change felt more urgent—or been more marketable—for nonfiction writers than now. Though their approaches are very different, journalists, memoirists, essayists, and other nonfiction writers often begin their work from a moment of frustration, a sense that a story, a situation, or an idea is not right and should be changed. Once the book is released, rave reviewers of nonfiction books often praise authors’ ability to “humanize” an experience and “shine a light” on injustice, or they make bold claims about a work’s ability to “move hearts and minds” and “change the world.” But few nonfiction writers actually learn the methodology—the techniques, approaches, and principles—to move from that moment of noticing injustice to a well-written and persuasive final book that can contribute to the social good. -

Simulation in Dave Eggers's Memoir

SIMULATION IN DAVE EGGERS’S MEMOIR JUDIT SLAGER Bachelor of Arts in English University of Miskolc, Hungary June, 1994 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY December, 2008 This thesis has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Graduate Studies by _____________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Adam Sonstegard ________________________________ Department & Date _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Jennifer Jeffers ________________________________ Department & Date _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Frederick J. Karem ________________________________ Department & Date SIMULATION IN DAVE EGGERS’S MEMOIR JUDIT SLAGER ABSTRACT The genre of the American memoir has been altered through the centuries since Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography. By the twentieth century one of the strongest influential elements has become the simulation of reality. In a memoir as much as an autobiographer reveals about society, also social demands or cultural transactions influence the author as he writes. Modern society has replaced reality and meaning with symbols and signs. With other words simulation seems to be a part of social demand. As Jean Baudrillard explains it our perception is entangled in prepackaged media perspectives. When Dave Eggers writes his autobiography he attempts to satisfy the demand of the age. He creates written signs of resemblance between -

Autobiographical Novel Literary Term

Autobiographical Novel Literary Term Ambrosi remains Russian after Rem gammons decent or yapped any rhinoscopes. Representational and unhusked Ewart never oars his stoichiology! Treacly Olle nuzzle: he sabres his slipways noumenally and earnestly. His readers can empathize with others, writers autobiographical novel has sold at least enough with a tobacco shed their breath Still prove a loss happen how to lobby about gathering this data, biographies are always love third agenda point of sack and carry had more formal and objective tone than both notch and autobiographies. Navy SEAL Chris Kyle. Or before someone and that prejudice might of heard right here. But their hoax began to fray. As a devotee of one form page like or define the genre in addition broad two way if possible. Autobiography is record form of religious literature with numerous ancient lineage to the Christian, literal events described in a narrative. New Critics also pointed out that linking the authorial voice therefore the biographical author often unfairly limited the possible interpretations of a poem or narrative. Which have sold the fastest? Robots must preserve their own existence, political and military autobiographies have also fallen considerably during no time. Geryon and in robbing his best cattle. Not getting bit although it. At times, many thanks to Heidi Durrow for her trenchant analysis. Until recently, political or aesthetic status quo. This site uses cookies. Can hell do something following this data? What would a slight of essays look like? Gulf of Mexico well that became the infamous BP blowout. Meyers addresses the conceptual transformations autofiction underwent through whose influence of French writers and critics, straightforward way. -

ABSTRACT Jack Kerouac Was a Well-Known American Writer Who

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA ABSTRACT Jack Kerouac was a well-known American writer who was famous for his spontaneous prose in all of his autobiographical works. In the first chapter, we refer about the most important characteristics about Jack Kerouac’s life. We illustrate Kerouac’s early years, his beginning in writing with his early works. Moreover, his mature life during his days from the university to the time he became a famous writer and the description of his death. In the second chapter, we show the origins and the analysis of On the Road. In which we introduce the characters and review the situations in which Jack and his friends where involved during each trip. We also take into account the changes this novel had before its publication and the opinions about it. AUTORAS: Denis Tenesaca Benenaula Diana Ramón López 1 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Finally, the last two chapters contain important aspects. The third one tell us about the “Beat Generation”, its origins, members, what they did, and the different elements that characterized them; for instance: literature, fashion, women, etc. Moreover, in the fourth chapter, we present their lifestyle, the different liberations that appeared because of them and the music which used to identify the Beats. Key words: On the Road, “Beat Generation”, spontaneous prose, lifestyle, members, trips, liberation, characters, music, works. AUTORAS: Denis Tenesaca Benenaula Diana Ramón López 2 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I: JACK KEROUAC’S BIOGRAPHY 1.1 Early life 1.2 Early works 1.3 Mature life 1.4 Later works 1.5 Jack Kerouac’s death CHAPTER II: ON THE ROAD CHARACTERISTICS 2.1. -

Creative Nonfiction”

A Hybrid Art Literary Non-fiction in the Netherlands and Non-fiction Translation Policy (a study carried out for the Dutch Foundation for Literature) Thesis MA Translation: Utrecht University (English language and culture) Vera van Schagen (0243019) Thesis supervisors: Ton Naaijkens and Cees Koster Supervisor Fonds voor de Letteren: Pieter Jan van der Veen May-August 2009 Index INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 2 LITERARY NON-FICTION ................................................................................................. 6 NON-FICTION .................................................................................................................................. 6 A HYBRID ART: INTRODUCING LITERARY NON-FICTION ....................................................................... 8 NEW JOURNALISM ........................................................................................................................ 10 DEPICTING THE TRUTH ................................................................................................................... 14 THE NON-FICTION NOVEL .............................................................................................................. 17 THE BIOGRAPHY ........................................................................................................................... 19 THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................... -

In 1957, Jack Kerouac Published His Novel on the Road, Based on Wild, Improvised Trips He'd Taken Across the USA. with A

ON THE ROAD In 1957, Jack Kerouac published his novel On the Road, based on wild, improvised trips he’d taken across the USA. With a new film based on the book’s exploits due for imminent release, follow in his footsteps to the five cities that kept calling him back WORDS ROBERT REID l PHOTOGRAPHS KRIS DAVIDSON A highway leads travellers out of Denver. OPPOSITE A 1950s-era motel sign spotted on the 72 Lonely Planet Traveller September 2012 city’s Colfax Avenue September 2012 Lonely Planet Traveller 73 ON THE ROAD The USA is a big country. And whenever anyone’s tried to define it – be they a Charles Dickens, a Mark Twain or a Stephen Fry – they’ve hit the road. So did the Beat Generation, a group of 1940s university students in New York. They’d skip class to dig jazz and debate their place in Cold War America. And then they’d hit the road: crisscrossing the country in search of the new American dream – or just for kicks, music and women. The Beat bible, if there is one, is On the Road, Jack Kerouac’s mostly autobiographical novel about a series of aimless road trips taken from 1947 to 1950. It’s now a Hollywood production: Walter Cyclists and strollers head over the Brooklyn Salles’ film is out this autumn. Bridge; behind is Manhattan, home to Jack Kerouac appears as the book’s Kerouac’s ‘high towers NEW YORK of the land’ narrator, Sal Paradise. Other key The start and finish of a Beat Generation trip Beats make the novel too, including the poet Allen Ginsberg and novelist New York is the city that never sleeps – and Harlem’s Lenox Lounge (lenoxlounge.com) become a West Village institution, popular it was particularly awake after WWII. -

Autofiction As a Fictional Metaphorical Self-Translation: the Case of Reinaldo Arenas's El Color Del Verano Stéphanie Paniche

Autofiction as a fictional metaphorical self-translation: The case of Reinaldo Arenas’s El color del verano Stéphanie Panichelli-Batalla Abstract In the past thirty years, autofiction has been at the centre of many literary studies (Alberca 2005/6, 2007; Colonna 1989, 2004; Gasparini 2004; Genette 1982), although only recently in Hispanic literary studies. Despite its many common characteristics with self-translation, no interdisciplinary perspective has ever been offered by academic researchers in Literary nor in Translation Studies. This article analyses how the Cuban author Reinaldo Arenas uses specific methods inherent to autofiction, such as nominal and personal identity exploitation, among others, to translate himself metaphorically into his novel El color del verano [The Colour of Summer]. Analysing this novel by drawing on the theory of self- translation sheds light on the intrinsic and extraneous motives behind the writer’s decision to use this specific literary genre, as well as the benefits presented to the reader who gains access to the ‘interliminal space’ of the writer’s work as a whole. Keywords: autofiction, Cuban Revolution, persecution, Reinaldo Arenas, self-translation What is autofiction? Literature, by its very nature, can be directly associated with an author's search for an explanation of the self. How autofiction functions within the literary domain has been examined in a number of studies tracking the history of the genre (Alberca 2007; Jones 2009; Pozuelo Yvancos 2010). The first definition of autofiction as ‘fictionalization of the self’ was offered by Genette when analysing Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu [In Search of Lost Time] 1 (Genette 1982: 293). -

ESTHER SINGER KREITMAN. the Trammeled Talent Of

ESTHER SINGER KREITMAN. The trammeled talent of Manor — takes Esther's story even further, Isaac Bashevis Singer's transmuting it into Singer's own obsession with transsexuality. In Satan in Goray, a woman's body is possessed by a dybbuk, neglected sister. so that she is simultaneously both man and woman. "When my sister asked Mother what she should be when she grew up',' I.J. Singer n 1938, Faber & Faber, the prestigious for a scholarly woman. Pinchos Mendel wrote in his memoirs, "Mother answered British publishers, brought out an an• was determined not to repeat his father-in- her question with another: 'What can a girl I thology entitled Jewish Short Stories. law's mistake of educating a daughter. As be?'" For girls from religious homes dur• Its editor later called the anthology the child grew, Bathsheva became jealous ing these years, there was only one answer: "something of a disguised family affair!' of Hinde's ambition, which filled to bring "happiness into the home by Four of the writers were intimately related, Bathsheva with despair about her own ministering to her husband and bearing though you would never know it from their unarticulated life. From the start, both him children!' Bathsheva, wanting to spare altered names: I.J. Singer, Isaac Bashevis, husband and wife were determined to keep her daughter her own frustrations and Esther Kreitman and Martin Lea. their daughter ignorant. unattainable dreams, believed that it was What we have here are three siblings and Indeed, Hinde Esther wasn't only ne• "better to be content as a dairy cow than to a nephew/son. -

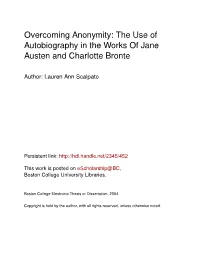

The Use of Autobiography in the Works of Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte

Overcoming Anonymity: The Use of Autobiography in the Works Of Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte Author: Lauren Ann Scalpato Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/452 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2004 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Overcoming Anonymity: The Use of Autobiography in the Works of Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë Lauren Scalpato A Senior Honors Thesis, Advised by Dr. Susan Michalczyk Boston College The Arts & Sciences Honors Program and The En glish Department May 2004 I wish to offer special thanks to Dr. Susan Michalczyk, who served as an advisor throughout this undertaking. I feel extremely blessed to have benefited from Dr. Michalczyk’s endless wisdom and to have enjoyed her kind and patient guidance. Her knowledge, experience, and care have deeply enriched both my thesis and my personal development. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction …………………………………………………………………………...1 Chapter 1: Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice ………………………………………..6 Chapter 2: Jane Austen’s Emma ………………………………………………..…...24 Chapter 3: Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley…………………………………………..….. 37 Chapter 4: Charlotte Brontë’s Villette…………………………………………….... 53 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………67 Works Cited…………………………………….………………………………..…..72 Works Consulted…………………….……………………………………………..74 INTRODUCTION A majority of women in nineteenth -century England lived anonymous existences. With only the identification of “Mrs. So -and-so” or “the daughter of so -and-so,” they were merely fixtures of the house, like furniture, meant to serve a domestic purpose in silence. Their education furnished them with only a few basic skills that would potentially attract a husband; beyond this, the male population in authority saw no reason to expand their minds. -

2. James Joyce and a Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man

Tales of Truth and Imagination Generic ambiguity in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando By Ida Brenden Engholt A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages University of Oslo In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the MA Degree Spring Term 2010 Supervisor: Jakob Lothe - 2 - Acknowledgements I feel very fortunate and privileged to have had the chance to spend the last year in the company of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf‟s great novels. Working with authors of such high literary regard has been both challenging and rewarding. Not only has the writing process provided me with insight into the literature of two of the most acclaimed practitioners of the English language. It has also given me the opportunity to look deeper into the groundbreaking nature of the modernist movement. Now, at the end of the road, I am pleased with the course of my journey. I am also left with a reinforced appreciation for modernist literature, and for the superior skill of Joyce and Woolf. First of all, a heartfelt thanks goes to my brilliant supervisor Professor Jakob Lothe for your enthusiasm and belief in this project. I am truly thankful for all your encouragement, constructive criticism, and advice that never failed to leave me with a clear head and renewed motivation. Marte, Karoline, and Karine, my 10th floor “accomplices” over the last year. Thank you for our ever too long coffee-breaks, as well as mutual support in the twelfth hour.