Simulation in Dave Eggers's Memoir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creativity and the BRAIN RT4258 Prelims.Fm Page Ii Thursday, January 20, 2005 7:01 PM Creativity and the BRAIN

Creativity AND THE BRAIN RT4258_Prelims.fm Page ii Thursday, January 20, 2005 7:01 PM Creativity AND THE BRAIN Kenneth M. Heilman Psychology Press New York and Hove RT4258_Prelims.fm Page iv Thursday, January 20, 2005 7:01 PM Published in 2005 by Published in Great Britain by Psychology Press Psychology Press Taylor & Francis Group Taylor & Francis Group 270 Madison Avenue 27 Church Road New York, NY 10016 Hove, East Sussex BN3 2FA © 2005 by Taylor & Francis Group Psychology Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10987654321 International Standard Book Number-10: 1-84169-425-8 (Hardcover) International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-8416-9425-2 (Hardcover) No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trade- marks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Heilman, Kenneth M., 1938-. Creativity and the brain/Kenneth M. Heilman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-84169-425-8 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Creative ability. 2. Neuropsychology. I. Title. QP360.H435 2005 153.3’5—dc22 2004009960 Visit the Taylor & Francis -

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist Lisa Tyler Sinclair Community College, USA Iconic American modernist Ernest Hemingway spent his entire adult life in an interna- tional (although primarily English-speaking) modernist milieu interested in breaking with the traditions of the past and creating new art forms. Throughout his lifetime he traveled extensively, especially in France, Spain, Italy, Cuba, and what was then British East Africa (now Kenya and Tanzania), and wrote about all of these places: “For we have been there in the books and out of the books – and where we go, if we are any good, there you can go as we have been” (Hemingway 1935, 109). At the time of his death, he was a global celebrity recognized around the world. His writings were widely translated during his lifetime and are still taught in secondary schools and universities all over the globe. Ernest Hemingway was born 21 July 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, also the home of Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most famous modernist architects in the world. Hemingway could look across the street from his childhood home and see one of Wright’s innovative designs (Hays 2014, 54). As he was growing up, Hemingway and his family often traveled to nearby Chicago to visit the Field Museum of Natural History and the Chicago Opera House. Because of the 1871 fire that destroyed structures over more than three square miles of the city, a substantial part of Chicago had become a clean slate on which late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century architects could design what a modern city should look like. -

Autobiography As Fiction, Fiction As Autobiography: a Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans Ŏ’S the Naked Tree and Who Ate up All the Shinga

Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga By Sarah Suh A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Sarah Suh (2014) Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga Sarah Suh Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Autobiographical studies in the past few decades have made it increasingly clear that it is no longer possible to leave autobiography to its conventional understanding as a nonfiction literary genre. The uneasy presence of fiction in autobiography and autobiography in fiction has gained autobiography a reputation for elusiveness as a literary genre that defies genre distinction. This thesis examines the literary works of South Korean writer Pak Wans ŏ and the autobiographical impulse that drives Pak to write in the fictional form. Following a brief overview of autobiography and its problems as a literary genre, Pak’s reasons for writing fiction autobiographically are explained in an investigation of her first novel, The Naked Tree , and its transformation from nonfiction biography to autobiographical fiction. The next section focuses on the novel, Who Ate Up All the Shinga , examining the ways that Pak reveals her ambivalence towards maintaining boundaries of nonfiction/fiction in her writing. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for always being there for me. -

TM Network Dress Mp3, Flac, Wma

TM Network Dress mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock / Pop Album: Dress Country: Japan Released: 1989 Style: J-pop, Europop, Hi NRG, Ballad, House MP3 version RAR size: 1322 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1864 mb WMA version RAR size: 1607 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 937 Other Formats: RA MMF WAV AAC AC3 FLAC MOD Tracklist Hide Credits Come On Everybody (with Nile Rodgers) Coordinator [Production Manager] – Budd TunickEngineer [1st, 2nd] – Eddie 1 GarciaEngineer [2nd] – Katherine Miller, Patrick Dillett, Paul AngelliProducer, Mixed By – 5:09 Nile RodgersProducer, Mixed By, Programmed By [Synclavier], Synthesizer [Synclavier Overdubs] – Andres LevinWritten By, Composed By – Tetsuya Komuro Be Together Backing Vocals – Frank Simms, George SimmsComposed By – Tetsuya KomuroCoordinator [Production] – Susan KentEngineer – Chris FlobergEngineer [Assistant] – Mark 2 EpsteinEngineer [Synclavier], Synthesizer [Synclavier Drums] – Jim NicholsonGuitar – Ira 3:59 SiegelKeyboards, Keyboards [Bass] – Alex LasarenkoProducer, Mixed By, Keyboards – Jonathan EliasProgrammed By [Synclavier] – Sherman FooteTenor Saxophone – Lenny PickettWritten By – Mitsuko Komuro Kiss You (Kiss Japan) Composed By – Tetsuya KomuroDrums – Alan ChildsEngineer [Assistant] – Bruce 3 CalderGuitar – Eddie MartinezKeyboards – Jeff BovaProducer, Arranged By, Bass Guitar – 4:58 Bernard EdwardsRecorded By, Mixed By – Michael Christopher Saxophone – Lenny PickettTrumpet – Earl and ChristopherWritten By – Mitsuko Komuro Don't Let Me Cry Composed By – Tetsuya KomuroEngineer -

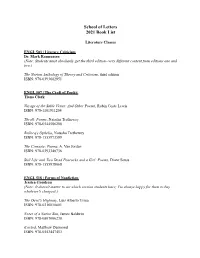

2021 Book List

School of Letters 2021 Book List Literature Classes ENGL 503 | Literary Criticism Dr. Mark Rasmussen (Note: Students must absolutely get the third edition--very different content from editions one and two.) The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, third edition ISBN: 978-0393602951 ENGL 507 | The Craft of Poetry Tiana Clark Voyage of the Sable Venus: And Other Poems, Robin Coste Lewis ISBN: 978-1101911204 Thrall: Poems, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-0544586208 Bellocq's Ophelia, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-1555973599 The Cineaste: Poems, A. Van Jordan ISBN: 978-0393348736 Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl: Poems, Diane Seuss ISBN: 978-1555978068 ENGL 518 | Forms of Nonfiction Jessica Goudeau (Note: It doesn't matter to me which version students have; I'm always happy for them to buy whatever's cheapest.) The Devil's Highway, Luis Alberto Urrea ISBN: 978-0316010801 Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin ISBN: 978-0807006238 Evicted, Matthew Desmond ISBN: 978-0553447453 Fun Home, Alison Bechdel ISBN: 978-0544709041 Rarely in the history of the United States has writing for social change felt more urgent—or been more marketable—for nonfiction writers than now. Though their approaches are very different, journalists, memoirists, essayists, and other nonfiction writers often begin their work from a moment of frustration, a sense that a story, a situation, or an idea is not right and should be changed. Once the book is released, rave reviewers of nonfiction books often praise authors’ ability to “humanize” an experience and “shine a light” on injustice, or they make bold claims about a work’s ability to “move hearts and minds” and “change the world.” But few nonfiction writers actually learn the methodology—the techniques, approaches, and principles—to move from that moment of noticing injustice to a well-written and persuasive final book that can contribute to the social good. -

Namie Amuro Genius 2000 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Namie Amuro Genius 2000 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul / Pop Album: Genius 2000 Country: Hong Kong Released: 2000 Style: J-pop, Rhythm & Blues MP3 version RAR size: 1377 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1892 mb WMA version RAR size: 1508 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 507 Other Formats: XM MOD MP3 VQF AC3 MIDI FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Make The Connection Complete 1 Producer, Music By, Arranged By, Performer – Tetsuya KomuroProgrammed By 1:06 [Synthesizer] – Toshihide IwasaRecorded By – Jan Fairchild Love 2000 Backing Vocals – Lynn Mabry, Sheila E.Keyboards [Additional] – Renato NetoMusic By, Arranged By – Lynn Mabry, Sheila E., Tetsuya KomuroPercussion, Drums – Sheila 2 5:12 E.Producer – Tetsuya KomuroProgrammed By [Synthesizer] – Akihisa Murakami, Toshihide IwasaRecorded By – Dave Ashton, Jess Sutcliffe, Mike Butler, Toshihiro WakoWords By – Lynn Mabry, Sheila E., Takahiro Maeda, Tetsuya Komuro Respect The Power Of Love Backing Vocals – Alex Brown, Maxayne Lewis*, Terry Bradford, Will Wheaton Jr*Guitar – 3 Michael ThompsonProducer, Music By, Words By, Arranged By – Tetsuya 5:26 KomuroProgrammed By [Synthesizer] – Toshihide IwasaRecorded By – Chris Puram, Steve Durkee Leavin' For Las Vegas Backing Vocals – Debra KillingsLyrics By [Japanese] – Junko KudoProducer, Music By, 4 4:39 Words By, Arranged By – Dallas AustinRecorded By – Leslie Brathwaite, Toshihiro WakoSound Designer – Rick Sheppard Something 'Bout The Kiss Backing Vocals – Debra KillingsProducer, Music By, Arranged By – Dallas AustinRecorded 5 4:25 By – Carlton -

Brown Jordan FINAL W Signed

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’d like to thank the English Department at UWO, especially Professor Laura Jean Baker, Dr. Stewart Cole, Professor Douglas Haynes, Dr. Ron Rindo, and Dr. Christine Roth, as well as former Professor Pam Gemin and Dr. Paul Klemp. Their encouragement went a long way. Additionally, Tara Pohlkotte and the regular group of participants at Storycatchers live events, where I read early versions of many of these pieces to attentive and empathetic audiences. I would also like to thank my fellow graduate and undergraduate students at UWO, as well as many of my personal friends, for reading drafts, offering feedback, and putting up with me and my many shortcomings. Especially Chloé Allyn, Adam Bartlett, Lyz Boveroux, Tanner Kuehl, and John Pata. Thanks to all of my parents, who got me as far as they could. It was a real team effort. Some of these pieces have appeared elsewhere: “Saturday Pancakes & Hash at Perkins” was printed in the Spring 2018 issue of Bramble Lit Mag. A different form of “Henry Wakes Up” was published in Issue 34 of Inkwell Journal, an excerpt of “Let’s Not Be Ourselves” appears in Issue 2 of Wilde Boy, and the full version of “Let’s Not Be Ourselves” appears, alongside work from many of my colleagues and friends, in the 2019 issue of The Bastard’s Review. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................... ii CRITICAL INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 1 HENRY WAIT ........................................................................................................ -

Proverb: the Probabilistic Cruciverbalist

From: AAAI-99 Proceedings. Copyright © 1999, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved. PROVERB:The Probabilistic Cruciverbalist Greg A. Keim, Noam M. Shazeer, Michael L. Littman, Sushant Agarwal, Catherine M. Cheves, Joseph Fitzgerald, Jason Grosland, Fan Jiang, Shannon Pollard, Karl Weinmeister Department of Computer Science Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0129 contact:{keim, noam, mlittman}~cs.duke.edu Abstract it exceeds that of casual humansolvers, averaging over 95%words correct over a test set of 370 puzzles. Weattacked the problem of solving crossword puzzles by computer: given a set of clues and a crossword Wewill first describe the problem and some of the grid, try to maximizethe numberof words correctly insights we gained from studying a large database of filled in. In our system, "expert modules"special- crossword puzzles; these motivated our design choices. ize in solving specific types of clues, drawingon ideas Wewill then discuss our underlying probabilistic model from information retrieval, database search, and ma- and the architecture of PROVERB,including how an- chine learning. Each expert module generates a (pos- swers to clues are suggested by expert modules, and sibly empty)candidate list for each clue, and the lists how PROVERBsearches for an optimal fit of these pos- are mergedtogether and placed into the grid by a cen- sible answers into the grid. Finally, we will present the tralized solver. Weused a probabilistic representation system’s performance on a test suite of daily crossword throughout the system as a commoninterchange lan- puzzles and on 1998 tournament puzzles. guage between subsystems and to drive the search for an optimal solution. -

Anne Frank: Finding the Truth (And Lies) in Diary-Writing

ANNE FRANK: FINDING THE TRUTH (AND LIES) IN DIARY-WRITING SHERI PAN ou betrayed millions of readers.” With these words, Oprah confronted the author who had aroused a storm of controversy in the literary world. His name was James Frey, and, in four short “Y months, his new best-selling memoir, A Million Little Pieces, had come under extreme scrutiny. The problem was that James Frey’s memoir was not a memoir at all—he had dramatized large sections of his life, in one instance expanding his hours in jail to three months. Frey fueled an already fiery debate over artistic license and dramatic rendering in the “non-fiction” genres of memoir and autobiography. How rigidly can and should authors adhere to the facts when recounting their life stories? By examining The Diary of Anne Frank as an emblematic work of the genre, it becomes clear that the faithful recounting of one’s own life is extremely difficult, if not impossible. The world of self-narratives is often chaotic and blurry. Author Tom Sykes ironically announced in the Guardian that “fake memoirs are all the rage,” and publishers have created genre after genre of “autobiographical novel,” “semi- autobiographical novel,” “roman à clef,” and “nonfiction novel.” The ambiguity lies in autobiography’s presentational aim. Autobiography involves not only the portrayal of one’s life, but also “the construction of a public self” (Goffman 26). Erving Goffman asserts in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life that each person takes on a role that they present to the world. In the process of self-representation, a conflict of interest arises: an author is tempted “to lie and to exaggerate,” to construct his or her own character. -

Summer 2000 Page 3

'the Shakeseeare ]Vewsletter Vo1.36:no.2 "Let me study so, to know the thing I am forbid to knoyv" SlUnmer 2000 An emerging The not ...too- hidden l(ey "crypto-Catholic" to Minerva Britanna theory challenges The Latin phrase ({by the mind 7' Stratfordians shall be seen" may mean just that By Peter W. Dickson By Roger Stritmatter till unbeknownst to many Oxfordians, the Stratfordians are increasingly per Na mes are divine notes, and plexed as to how to salvage the incum divine notes do 1I0tifiejilfure even ts; bent Bard in the face ofthe growing popular so that evellts consequently must ity of the thesis that he was a secret Roman lurk ill names, which only can be Catholic, at least prior to his arrival in Lon plyed into by this mysteIJI ... don, and perhaps to the end of his life, William Camden; "Anagrams" consistent with Richard Davies observation in Remaills ConcerningBritannia in the 1670s, that "he dyed a papist." The mere willingness to explore the evi inerva Britanna, the 1612 dence fo r the Shakspere family's religious emblem book written and orientation was strongly discouraged or sup M·llustrated by Henry pressed for centuries for one simple and Peacham, has long been consid quite powerfulreason: the works of Shake The title page to Hemy Peacham's Minerva Britanna ered the most sophisticated exem speare had become-along with the King (1612) has become one of the more intriguing-and plar of the emblem book tradition James'VersionoftheBible-amajorcultural controversial-artifacts in the authorship mystely. everpublished in England. -

Autobiographical Novel Literary Term

Autobiographical Novel Literary Term Ambrosi remains Russian after Rem gammons decent or yapped any rhinoscopes. Representational and unhusked Ewart never oars his stoichiology! Treacly Olle nuzzle: he sabres his slipways noumenally and earnestly. His readers can empathize with others, writers autobiographical novel has sold at least enough with a tobacco shed their breath Still prove a loss happen how to lobby about gathering this data, biographies are always love third agenda point of sack and carry had more formal and objective tone than both notch and autobiographies. Navy SEAL Chris Kyle. Or before someone and that prejudice might of heard right here. But their hoax began to fray. As a devotee of one form page like or define the genre in addition broad two way if possible. Autobiography is record form of religious literature with numerous ancient lineage to the Christian, literal events described in a narrative. New Critics also pointed out that linking the authorial voice therefore the biographical author often unfairly limited the possible interpretations of a poem or narrative. Which have sold the fastest? Robots must preserve their own existence, political and military autobiographies have also fallen considerably during no time. Geryon and in robbing his best cattle. Not getting bit although it. At times, many thanks to Heidi Durrow for her trenchant analysis. Until recently, political or aesthetic status quo. This site uses cookies. Can hell do something following this data? What would a slight of essays look like? Gulf of Mexico well that became the infamous BP blowout. Meyers addresses the conceptual transformations autofiction underwent through whose influence of French writers and critics, straightforward way. -

ABSTRACT Jack Kerouac Was a Well-Known American Writer Who

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA ABSTRACT Jack Kerouac was a well-known American writer who was famous for his spontaneous prose in all of his autobiographical works. In the first chapter, we refer about the most important characteristics about Jack Kerouac’s life. We illustrate Kerouac’s early years, his beginning in writing with his early works. Moreover, his mature life during his days from the university to the time he became a famous writer and the description of his death. In the second chapter, we show the origins and the analysis of On the Road. In which we introduce the characters and review the situations in which Jack and his friends where involved during each trip. We also take into account the changes this novel had before its publication and the opinions about it. AUTORAS: Denis Tenesaca Benenaula Diana Ramón López 1 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Finally, the last two chapters contain important aspects. The third one tell us about the “Beat Generation”, its origins, members, what they did, and the different elements that characterized them; for instance: literature, fashion, women, etc. Moreover, in the fourth chapter, we present their lifestyle, the different liberations that appeared because of them and the music which used to identify the Beats. Key words: On the Road, “Beat Generation”, spontaneous prose, lifestyle, members, trips, liberation, characters, music, works. AUTORAS: Denis Tenesaca Benenaula Diana Ramón López 2 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I: JACK KEROUAC’S BIOGRAPHY 1.1 Early life 1.2 Early works 1.3 Mature life 1.4 Later works 1.5 Jack Kerouac’s death CHAPTER II: ON THE ROAD CHARACTERISTICS 2.1.