Writing the Self ENGLISH STUDIES 5 Giulia Grillo Mikrut Mikrut Shands Grillo by Pattanaik W Giulia Edited R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Rhetoric and Sonic Composing Processes Kyle D

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Musical Rhetoric and Sonic Composing Processes Kyle D. Stedman University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Scholar Commons Citation Stedman, Kyle D., "Musical Rhetoric and Sonic Composing Processes" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4229 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Musical Rhetoric and Sonic Composing Processes by Kyle D. Stedman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Joseph M. Moxley, Ph.D. Trey Conner, Ph.D. Marc Santos, Ph.D. Meredith Zoetewey, Ph.D. Date of approval: June 12, 2012 Keywords: Music, Sound, Composition, Creativity, Aesthetics Copyright © 2012, Kyle D. Stedman DEDICATION I dedicate this project to Margo, who partnered with me through writing marathons, bad moods, cluttered desks, long conferences, and endless drives between Orlando and Tampa. She never stopped speaking truth into me and reminding me how good I am at this whole teacher/scholar thing. And she filled our home with music, the best writing support of all. I also owe a debt to the fifteen composers who took the time to talk to me about their work, as well as all the composers over the years who have translated their musical instincts into words through interviews. -

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist Lisa Tyler Sinclair Community College, USA Iconic American modernist Ernest Hemingway spent his entire adult life in an interna- tional (although primarily English-speaking) modernist milieu interested in breaking with the traditions of the past and creating new art forms. Throughout his lifetime he traveled extensively, especially in France, Spain, Italy, Cuba, and what was then British East Africa (now Kenya and Tanzania), and wrote about all of these places: “For we have been there in the books and out of the books – and where we go, if we are any good, there you can go as we have been” (Hemingway 1935, 109). At the time of his death, he was a global celebrity recognized around the world. His writings were widely translated during his lifetime and are still taught in secondary schools and universities all over the globe. Ernest Hemingway was born 21 July 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, also the home of Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most famous modernist architects in the world. Hemingway could look across the street from his childhood home and see one of Wright’s innovative designs (Hays 2014, 54). As he was growing up, Hemingway and his family often traveled to nearby Chicago to visit the Field Museum of Natural History and the Chicago Opera House. Because of the 1871 fire that destroyed structures over more than three square miles of the city, a substantial part of Chicago had become a clean slate on which late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century architects could design what a modern city should look like. -

Land Reform Is Basically a Class Issue”

This land is my land! Motions and emotions around land reform in Namibia Erika von Wietersheim 1 This study and publication was supported by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Namibia Office. Copyright: FES 2021 Cover photo: Kristin Baalman/Shutterstock.com Cover design: Clara Mupopiwa-Schnack All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written permission of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. First published 2008 Second extended edition 2021 Published by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Namibia Office P.O. Box 23652 Windhoek Namibia ISBN 978-99916-991-0-3 Printed by John Meinert Printing (Pty) Ltd P.O. Box 5688 Windhoek / Namibia [email protected] 2 To all farmers in Namibia who love their land and take good care of it in honour of their ancestors and for the sake of their children 3 4 Acknowledgement I would like to thank the Friedrich-Ebert Foundation Windhoek, in particular its director Mr. Hubert Schillinger at the time of the first publication and Ms Freya Gruenhagen at the time of this extended second publication, as well as Sylvia Mundjindi, for generously supporting this study and thus making the publication of ‘This land is my land’ possible. Furthermore I thank Wolfgang Werner for adding valuable up-to-date information to this book about the development of land reform during the past 13 years. My special thanks go to all farmers who received me with an open heart and mind on their farms, patiently answered my numerous questions - and took me further with questions of their own - and those farmers and interview partners who contributed to this second edition their views on the progress of land reform until 2020. -

Autobiography As Fiction, Fiction As Autobiography: a Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans Ŏ’S the Naked Tree and Who Ate up All the Shinga

Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga By Sarah Suh A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Sarah Suh (2014) Autobiography as Fiction, Fiction as Autobiography: A Study of Autobiographical Impulse in Pak Wans ŏ’s The Naked Tree and Who Ate Up All the Shinga Sarah Suh Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Autobiographical studies in the past few decades have made it increasingly clear that it is no longer possible to leave autobiography to its conventional understanding as a nonfiction literary genre. The uneasy presence of fiction in autobiography and autobiography in fiction has gained autobiography a reputation for elusiveness as a literary genre that defies genre distinction. This thesis examines the literary works of South Korean writer Pak Wans ŏ and the autobiographical impulse that drives Pak to write in the fictional form. Following a brief overview of autobiography and its problems as a literary genre, Pak’s reasons for writing fiction autobiographically are explained in an investigation of her first novel, The Naked Tree , and its transformation from nonfiction biography to autobiographical fiction. The next section focuses on the novel, Who Ate Up All the Shinga , examining the ways that Pak reveals her ambivalence towards maintaining boundaries of nonfiction/fiction in her writing. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for always being there for me. -

Slugmag.Com 1

slugmag.com 1 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 25 • Issue #311 • November 2014 • slugmag.com Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Coordinator: CONTRIBUTOR LIMELIGHT: Editor: Angela H. Brown Robin Sessions Managing Editor: Alexander Ortega Marketing Team: Alex Topolewski, Carl Acheson, Alex Springer Junior Editor: Christian Schultz Cassie Anderson, Cassandra Loveless, Ischa B., Janie Senior Staff Writer Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan Greenberg, Jono Martinez, Kendal Gillett, Lindsay Digital Content Coordinator: Henry Glasheen Clark, Raffi Shahinian, Robin Sessions, Zac Freeman Fact Checker: Henry Glasheen Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer Copy Editing Team: Alex Cragun, Alexander Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Ortega, Allison Shephard, Christian Schultz, Cody Distro: Andrea Silva, Daniel Alexander, Eric Kirkland, Henry Glasheen, John Ford, Jordan Granato, John Ford, Jordan Deveraux, Julia Sachs, Deveraux, Julia Sachs, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Maria Valenzuela, Michael Sanchez, Nancy Maria Valenzuela, Mary E. Duncan, Shawn Soward, Burkhart, Nancy Perkins, Phil Cannon, Ricky Vigil, Traci Grant Ryan Worwood, Tommy Dolph, Tony Bassett, Content Consultants: Jon Christiansen, Xkot Toxsik Matt Hoenes Senior Staff Writers: Alex Springer, Alexander Cover Photo: Chad Kirkland Ortega, Ben Trentelman, Brian Kubarycz, Brinley Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Froelich, Bryer Wharton, Christian Schultz, Cody Design Team: Chad Pinckney, Lenny Riccardi, Hudson, Cody Kirkland, Dean O. Hillis, Gavin Mason Rodrickc, Paul Mason Sheehan, Henry Glasheen, Ischa -

Oscar Peterson Motions and Emotions

Oscar Peterson Motions and Emotions Label:MPS Records (LC00979) Vertrieb: EDEL / Kontor New Media VÖ: 02. November 2018 EAN CD: 4029759128304 Kat-Nr. LP: 0212831MSW EAN LP: 4029759128311 www.mps-music.com Infos und Pressefotos: http://www.herzogpromotion.com Line-Up: Oscar Peterson (piano), Bucky Pizzarelli (guitar), Sam Jones (bass), Bob Durham (drums), Claus Ogerman (arranger) Track-Listing / ISRC: 1. Sally's Tomato (DEA116900160), 2. Sunny (DEN120408042), 3. By The Time I Get To Phoenix (DEN120408043), 4. Wandering (DEN120408044), 5. This Guy's In Love With You (DEA116900200), 6. Wave (DEA116900210), 7. Dreamsville (DEN120408045), 8. Yesterday (DEN120408046), 9. Eleanor Rigby (DEN120408047), 10. Ode To Billy Joe (DEN120408048) Oscar Peterson – Motions and Emotions In Trio-Besetzungen, als Solist und Mitmusiker der Singers Unlimited – so zeigte sich der Piano-Gigant Oscar Peterson bisher auf den Wiederveröffentlichungen aus dem MPS- Katalog. In der Serie Ambassadors for MPS offenbart der Kanadier nun mit einer von Till Brönner ausgewählten Einspielung aus dem Jahre 1969 ein weiteres spannendes Gesicht: Auf Motions And Emotions erleben wir ihn mit Jazzfassungen populärer Stücke aus Pop, Easy Listening und Songwriting als Protagonist eines Quartetts von langjährigen Begleitern, eingebettet in reiche Orchesterfarben. Gemalt hat sie ein Zauberer der Zunft, der großartige Claus Ogerman, zuvor auch schon in Diensten für Tom Jobim. Der Brasilianer ist denn auch mit seinem Standard „Wave“ vertreten, in dem das Orchester für Petersons fantastisch verschleppte Phrasierung eine leuchtende tropische Kulisse baut. Einem anderen großen Orchesterchef, Henry Mancini, erweisen Peterson und Ogerman in „Sally‘s Tomato“ mit federleicht trillernder Brillanz die Ehre. Eine Metamorphose fast ins Klassische hinein erfährt Jimmy Webbs „By The Time I Get To Phoenix“ – Ogerman öffnet hier mit den distanziert schwelgenden Streichern unendliche Klangräume. -

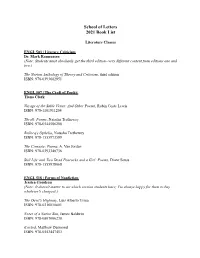

2021 Book List

School of Letters 2021 Book List Literature Classes ENGL 503 | Literary Criticism Dr. Mark Rasmussen (Note: Students must absolutely get the third edition--very different content from editions one and two.) The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, third edition ISBN: 978-0393602951 ENGL 507 | The Craft of Poetry Tiana Clark Voyage of the Sable Venus: And Other Poems, Robin Coste Lewis ISBN: 978-1101911204 Thrall: Poems, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-0544586208 Bellocq's Ophelia, Natasha Trethewey ISBN: 978-1555973599 The Cineaste: Poems, A. Van Jordan ISBN: 978-0393348736 Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl: Poems, Diane Seuss ISBN: 978-1555978068 ENGL 518 | Forms of Nonfiction Jessica Goudeau (Note: It doesn't matter to me which version students have; I'm always happy for them to buy whatever's cheapest.) The Devil's Highway, Luis Alberto Urrea ISBN: 978-0316010801 Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin ISBN: 978-0807006238 Evicted, Matthew Desmond ISBN: 978-0553447453 Fun Home, Alison Bechdel ISBN: 978-0544709041 Rarely in the history of the United States has writing for social change felt more urgent—or been more marketable—for nonfiction writers than now. Though their approaches are very different, journalists, memoirists, essayists, and other nonfiction writers often begin their work from a moment of frustration, a sense that a story, a situation, or an idea is not right and should be changed. Once the book is released, rave reviewers of nonfiction books often praise authors’ ability to “humanize” an experience and “shine a light” on injustice, or they make bold claims about a work’s ability to “move hearts and minds” and “change the world.” But few nonfiction writers actually learn the methodology—the techniques, approaches, and principles—to move from that moment of noticing injustice to a well-written and persuasive final book that can contribute to the social good. -

Genesys John Peel 78339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks

Sheet1 No. Title Author Words Pages 1 1 Timewyrm: Genesys John Peel 78,339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks 65,011 183 3 3 Timewyrm: Apocalypse Nigel Robinson 54,112 152 4 4 Timewyrm: Revelation Paul Cornell 72,183 203 5 5 Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible Marc Platt 90,219 254 6 6 Cat's Cradle: Warhead Andrew Cartmel 93,593 264 7 7 Cat's Cradle: Witch Mark Andrew Hunt 90,112 254 8 8 Nightshade Mark Gatiss 74,171 209 9 9 Love and War Paul Cornell 79,394 224 10 10 Transit Ben Aaronovitch 87,742 247 11 11 The Highest Science Gareth Roberts 82,963 234 12 12 The Pit Neil Penswick 79,502 224 13 13 Deceit Peter Darvill-Evans 97,873 276 14 14 Lucifer Rising Jim Mortimore and Andy Lane 95,067 268 15 15 White Darkness David A McIntee 76,731 216 16 16 Shadowmind Christopher Bulis 83,986 237 17 17 Birthright Nigel Robinson 59,857 169 18 18 Iceberg David Banks 81,917 231 19 19 Blood Heat Jim Mortimore 95,248 268 20 20 The Dimension Riders Daniel Blythe 72,411 204 21 21 The Left-Handed Hummingbird Kate Orman 78,964 222 22 22 Conundrum Steve Lyons 81,074 228 23 23 No Future Paul Cornell 82,862 233 24 24 Tragedy Day Gareth Roberts 89,322 252 25 25 Legacy Gary Russell 92,770 261 26 26 Theatre of War Justin Richards 95,644 269 27 27 All-Consuming Fire Andy Lane 91,827 259 28 28 Blood Harvest Terrance Dicks 84,660 238 29 29 Strange England Simon Messingham 87,007 245 30 30 First Frontier David A McIntee 89,802 253 31 31 St Anthony's Fire Mark Gatiss 77,709 219 32 32 Falls the Shadow Daniel O'Mahony 109,402 308 33 33 Parasite Jim Mortimore 95,844 270 -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

When the President Talks to God: a Rhetorical Criticism of Anti-Bush Protest Music

WHEN THE PRESIDENT TALKS TO GOD: A RHETORICAL CRITICISM OF ANTI-BUSH PROTEST MUSIC Megan O'Byrne A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2008 Committee: Michael L. Butterworth, Advisor Lara Martin Lengel Ellen W. Gorsevski ii ABSTRACT Michael L. Butterworth, Advisor Anti-war protest music has re-emerged onto the American songscape since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and the resulting military conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. This study works to explicate the ways in which protest music functions in the resultant culture of war. Protest music, as it reflects and creates culture, represents one possible site of productive change. Chapter 1 examines Ani DiFranco’s song “Self Evident” which was written as an immediate reaction to 9/11. Throughout this chapter I argue that protest music has the potential to work as a vehicle for consciousness raising. In Chapter 2 I consider the constitutive elements in the Bright Eyes song “When the President Talks to God.” Performed on The Tonight Show in May 2005, this song represents one of the first performances of dissent on national television after 9/11. This chapter also examines the limitations of Charland’s conception of the constituted public as it pertains to diverse and heterogeneous audiences. Ultimately, I argue that consciousness raising through music has the potential to bring listeners into the constituted subject position of those who dissent against war. iii Dedicated to the memory of Dr. Lewis (Lee) Snyder in whose shadow I will always walk. -

![Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:00 12 August 2016 a CLINICIAN’S GUIDE to SYSTEMIC SEX THERAPY](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3090/downloaded-by-new-york-university-at-04-00-12-august-2016-a-clinician-s-guide-to-systemic-sex-therapy-2353090.webp)

Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:00 12 August 2016 a CLINICIAN’S GUIDE to SYSTEMIC SEX THERAPY

Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:00 12 August 2016 A CLINICIAN’S GUIDE TO SYSTEMIC SEX THERAPY The second edition of A Clinician’s Guide to Systemic Sex Therapy has been com- pletely revised, updated, and expanded. This volume is written for beginning psychotherapy practitioners in order to guide them through the complexities of sex therapy and help them to be more effi cient in their treatment. The authors offer a unique theoretical approach to understanding and treating sexual prob- lems from a systemic perspective, incorporating the multifaceted perspectives of the individual client, the couple, the family, and the other contextual factors. Both beginning and experienced sex/relationship therapists will broaden their perspectives with the Intersystem approach and gain information rarely seen in sex therapy texts such as: how to thoroughly assess each sexual disor- der, the implementation of various treatment principles and techniques, how to incorporate homework, dealing with ethical dilemmas, understanding dif- ferent expressions of sexual behavior, and addressing the impact of medical problems on sexuality. Aside from bringing the diagnostic criteria up-to-date with the DSM 5, this new edition contains a new chapter on sensate focus, an expanded section on assessment, more information about development across the lifespan, and more focus on diversity issues throughout the text. Gerald R. Weeks, PhD, APBB, CST, is a certifi ed sex therapist with 30 years of practice experience and is a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He is among a handful of individuals to be given the “Outstanding Contribution to Mar- riage and Family Therapy” award in 2009 from the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapy, and was named the “2010 Family Psychologist of the Year.” He has published over 20 books in the fi elds of individual, couple, family, and sex therapy. -

Religion and Literature: C. S. Lewis and Tolkien Syllabus

1 Religion 4600/6600: Religion and Literature: C. S. Lewis and Tolkien Carolyn Jones Medine, Professor of Religion and in the Institute for African American Studies Office: 19 Peabody Hall Telephone: 706-542-5356 (messages) E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday and Wednesday 1:30-2:30 and by appointment Graduate Teaching Assistants: Noah Pollock, Jessica Couch, Eduardo Mendez I Course Description Religion and Literature’s goal is to examine the problematic of religion in the modern world and to explore basic human questions, such as those of identity, community, ethical action, and spirituality and how those have been expressed in literature. The language of such an exploration is sometimes specifically Christian; sometimes it interprets Christian language in new way, but often, the religious meanings are hybrid, using a number of traditions in syncretic ways. The first work in the field was on specifically Christian writers. We will, this semester, revisit that landscape. This course will examine the works of two of the group of writers who called themselves The Inklings: J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. Each was a Christian who expressed his faith through his art. We want to ask: Why do Christian writers—not just the Inklings, but also, for example, Walker Percy, Flannery O’Connor, Madeline L’Engle, and others—turn to fiction—in particular, to what Lewis and Tolkien called “the fairy story”—as a medium of expression of their ideas? What is gained or lost by such a choice? What is the relationship between art, imagination and belief? II Course Goals: In this course we will learn and come to: 1.