Waldemar PARUCH1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

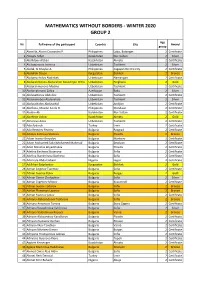

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 2 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abanilla, Alaina Cassandra P. Philippines Lobo, Batangas 2 Certificate 2 Abayev Aidyn Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Silver 3 Abdildaev Alzhan Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Certificate 4 Abduazimova Jasmina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 5 Abdul, Al Khaylar A. Philippines Cagayan De Oro City 2 Certificate 6 Abdullah Dayan Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 2 Bronze 7 Abdumazhidov Nodirbek Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 8 Abdurahmonov Abdurahim Boxodirjon O'G'Li Uzbekistan Ferghana 2 Gold 9 Abdurahmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 10 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 2 Silver 11 Abdusattorov Abdullox Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 12 Abduvahobov Abduvahob Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 13 Abduvohidov Abduvohid Uzbekistan Andijon 2 Certificate 14 Abellana, Maxine Anela O. Philippines Mandaue 2 Certificate 15 Abildin Ali Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Certificate 16 Abirkhan Adina Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Gold 17 Abrorova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 18 Ada Aydınok Turkey Izmir 2 Certificate 19 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 20 Adaliya Kalinova Stoilova Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Bronze 21 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 2 Certificate 22 Adam Mohamed Sabri Mohamed Mahmud Bulgaria Smolyan 2 Certificate 23 Adeli Nikolova Boyadzhieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 24 Adelina Encheva Stoianova Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 25 Adelina Stanimirova Docheva Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 26 Adenrele Abdul Jabaar Nigeria Lagos 2 Certificate -

Collaborative

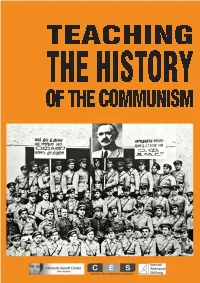

TEACHING THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNISM TEACHING THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNISM Published by: Hannah Arendt Center – Sofia 2013 This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies, the Hannah Arendt Center - Sofia and Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication receives funding from the European Parliament. The Centre for European Studies, the Hannah Arendt Center -Sofia, the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or any subsequent use of the information contained therein. Sole responsibility lies on the author of the publication. The processing of the publication was concluded in 2013 The Centre for European Studies (CES) is the political foundation of the European People’s Party (EPP) dedicated to the promotion of Christian Democrat, conservative and like-minded political values. For more information please visit: www.thinkingeurope.eu TEACHING THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNISM Editor: Vasil Kadrinov Print: AVTOPRINT www.avtoprint.com E-mail: [email protected] Phohe: +359 889 032 954 2 Kiril Hristov Str., 4000 Plovdiv, Bulgaria Teaching the History of the Communism Content Teaching the History of the Communist Regimes in Post-1989 Eastern Europe - Methodological and Sensitive Issues, Raluca Grosescu ..................5 National representative survey on the project: “Education about the communist regime and the european democratic values of the young people in Bulgaria today”, 2013 .......................................................14 Distribution of the data of the survey ...........................................................43 - 3 - Teaching the History of the Communism Teaching the History of the Communist Regimes in Post-1989 Eastern Europe Methodological and Sensitive Issues Raluca Grosescu The breakdown of dictatorial regimes generally implies a process of rewriting history through school curricula and textbooks. -

The Macedonian National Movement in the Pirin Part of Macedonia

Atanas Kiryakov and Aleksandar Donski MACEDONIA RISES THE MACEDONIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PIRIN PART OF MACEDONIA 1 Atanas KIRYAKOV and Aleksandar DONSKI MACEDONIA RISES THE MACEDONIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PIRIN PART OF MACEDONIA Published by the Macedonian Literary Association “Grigor Prlichev”, Sydney – Australia In collaboration with Institute for History and Archaeology “Goce Delcev” University - Stip Republic of Macedonia For the Publisher: Dushan RISTEVSKI * * * Translated by: Ljubica Bube DONSKA David RILEY (Great Britain) *** Macedonian Literary Association “Grigor Prlichev” P.O. Box 227 Rockdale NSW 2216 – Australia * * * Copyright by: Atanas Kiryakov and Aleksandar Donski National Library of Australia card number and ISBN 978-0-9808479-8-7 December, 2012 2 The book that you have in front of you presents a part of the documentation from the personal archive of the Macedonian activist Atanas Kiryakov from Blagoevgrad, which is dedicated to the struggle for the basic human and national rights of the Macedonians in the Pirin part of Macedonia and Bulgaria. People and events that Kiryakov himself directly or indirectly has met or attended are mentioned in here. This means that the book does not claim to contain ALL the documents from the struggles of the Macedonians under Pirin or that it contains all Macedonian activities, so the rest of the documents, notable people and descriptions of this struggle, remain to be published in later issues. From the editors 3 MAIN SPONSOR OF THE BOOK: Macedonian Orthodox Community of Australia 4 INSTEAD OF AN INTRODUCTION Before we move on to the basic subject of this book, we have to explain why the Macedonians were never Bulgarian, nor did they have ethnic Bulgarian origins, as it is claimed by the majority of Bulgarian governments and official organs. -

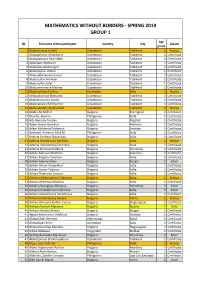

Mathematics Without Borders - Spring 2019 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - SPRING 2019 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abduazimova Jasmin Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 2 Abdugafforov Abdulboriy Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 3 Abdujabborov Rashidbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 4 Abdullaev Abdulaziz Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 5 Abdullaev Abdulmajid Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 6 Abdullayeva Amina Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 7 Abdurakhmanova Zarina Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 8 Abduraufov Amirhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 9 Abduraufov Zafar Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 10 Abduraxmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 11 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 1 Bronze 12 Abdusattorova Shahzoda Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 13 Abdushukurova Oysha Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 14 Abduvahidov Bahtiyornur Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 15 Abduvahobov Abduvohob Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 16 Abidin Ali Nedret Bulgaria Svilengrad 1 Certificate 17 Abordo, Keanne Philippines Iloilo 1 Certificate 18 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 1 Certificate 19 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 1 Certificate 20 Adam Mohamed Mahmud Bulgaria Smolyan 1 Certificate 21 Adelante, Ashanee Misk M Philippines Iloilo 1 Certificate 22 Adelina Encheva Stoyanova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 23 Adelina Stanimirova Docheva Bulgaria Sofia 1 Bronze 24 Adelina Vladislavova Drumeva Bulgaria Ruse 1 Certificate 25 Adelina Zhivkova Petkova Bulgaria Parvomay 1 Certificate 26 Adrian Adrianov Bozhilov Bulgaria Samokov 1 -

Perspectives and Problems of Romania and Bulgaria

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Basciani, Alberto Article Growth without development: The post-WWI period in the Lower Danube : perspectives and problems of Romania and Bulgaria The Journal of European Economic History Provided in Cooperation with: Associazione Bancaria Italiana, Roma Suggested Citation: Basciani, Alberto (2020) : Growth without development: The post-WWI period in the Lower Danube : perspectives and problems of Romania and Bulgaria, The Journal of European Economic History, ISSN 2499-8281, Associazione Bancaria Italiana, Roma, Vol. 49, Iss. 3, pp. 139-164 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/231565 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu 04-basciani_137_164.qxp_04-basciani_137_164 30/10/20 12:28 Pagina 139 Growth without Development: The Post-WWI Period in the Lower Danube. -

Bulgaria CHAPTER 2 – Bulgaria 2.1 the Struggle for Suffrage

CHAPTER 2 Bulgaria CHAPTER 2 – Bulgaria 2.1 The Struggle for Suffrage 2.1.1 The Congress of the Gypsies in Bulgaria 2.1 The Struggle for Suffrage Конгрес на циганите в България Жертви на българската демокрация – Циганите и Берлинският конгрес – Предварително събиране в цирк “България” Карл Маркс бе казал отдавна, че руската революция ще бъде начало на най-великото гражданско движение в Европа, но той не е подозирал какво крупно участие ще вземат в него циганите. Със своята метода на социалистически материализъм той не би могъл да открие тия съкровенни чувства на гражданственост, които са се криели в романтическата душа на циганите, и които трябваше да избухнат днес с една внушителна тържественост, която ще предизвика удивление на народите и ще увеличи грижите на Европа. Колкото до нас, българите, днешната манифе- стация е двойно важна: първо, защото бе изнесена наяве една вопиюща неправда, извършена от нашата демокрация върху едно антично племе; и второ, защото се установи от самите жертви, че сме нарушили с хладно съзнание една от свещен- ните клаузи на Берлинския договор. Нека България да благодари на високия такт и на политическата мъдрост на циганите, че не повдигнаха своя въпрос, дорде тра- еше морската демонстрация, защото в този случай щяхме да видим международна ескадра пред Варна и Бургас. Но докато дипломатическата опасност е отстранена досега, нравственият наш престиж пред Европа е вече силно накърнен: защото всички цивилизовани хора, които мислят, че в нашата материалистическа епоха и в нашето монотонно съществувание, циганите представляват поезията на волния и безгрижен живот, и идеализма на фантазията, няма да ни простят, че сме се пока- зали спрямо тях най-безсърдечни и несправедливи. -

The "Alternative" Socialism of Professor Alexander Tsankov

Articles The "Alternative" Socialism of Professor Alexander Tsankov Pencho D. Penchev* country. His influence is determined mainly by two factors. First he held important Summary: positions in the executive, legislature and had a major role in the political life of the The paper presents the economic country as Prime Minister, Speaker of the views and political activities of one of National Assembly, Minister of Education the most influential Bulgarian political and leader of the National Social Movement. economists – Alexander Tsankov. They From these positions, he had the opportunity were strongly influenced by his socialist to control and determine some of the most worldview. The socialism of professor important trends in Bulgaria’s economic Tsankov is alternative only if one accepts policy. He was also professor of political the self-definition of Marxism as the sole economy and Rector of Sofia University, scientific socialism. Then any deviation with a significant number of publications from orthodoxy should be considered as and thus he was able to influence the alternatives to scientifically based ideas. formation of part of the economic elite of In the context of what is seen as socialism Bulgaria. during the nineteenth and almost up to the The main thesis of this paper is that end of the twentieth century, the views of socialism is one of the main characteristics professor Tsankov are not a departure from, of economic views and had a strong impact but a variant of the socialism. He combined on the political activities of professor the elements which are characteristic of Tsankov. His socialism was not orthodox or social democracy and conservative statist "scientific" with respect to Marxist concepts, (and hence nationalistic) socialism. -

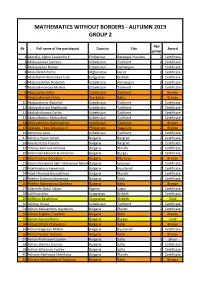

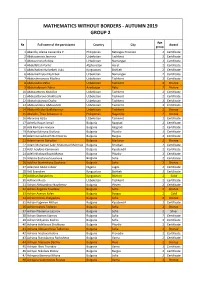

Mathematics Without Borders - Autumn 2019 Group 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - AUTUMN 2019 GROUP 2 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abanilla, Alaina Cassandra P. Philippines Batangas Province 2 Certificate 2 Abduazimova Jasmina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 3 Abduazizona Robiya Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 4 Abdulfattah Parhiz Afghanistan Herat 2 Certificate 5 Abdulhakim Nurlanbek Uulu Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 2 Certificate 6 Abdumazhidov Nodirbek Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 7 Abdurahmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 8 Abduraufov Zafar Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Bronze 9 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 2 Bronze 10 Abdusattorov Abdullox Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 11 Abdusattorova Shakhzoda Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 12 Abdushukurova Oysha Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 13 Abduvahobov Abduvahob Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 14 Abduvakhidov Bakhtiyornur Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Bronze 15 Abelado, Theo Sebastian A. Philippines Naga City 2 Bronze 16 Abrorova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 17 Achelia Hasan Ismail Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 18 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 19 Adaliya Kalinova Stoilova Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 20 Adam Genadievich Burmistrov Bulgaria Burgas 2 Certificate 21 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 2 Bronze 22 Adam Mohamed Sabri Mohamed MahmudBulgaria Smolyan 2 Certificate 23 Adel Ivaylova Kamenova Bulgaria Kyustendil 2 Certificate 24 Adeli Nikolova Boyadzhieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 25 Adelina Encheva Stoianova Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 26 Adelina -

Main Challenges for the Greek National Security Against the Geopolitical Changes in the Balkans During the Period 1918–1923

BALCANICA POSNANIENSIA XXVI Poznań 2019 MAIN CHALLENGES FOR THE GREEK NATIONAL SECURITY AGAINST THE GEOPOLITICAL CHANGES IN THE BALKANS DURING THE PERIOD 1918–1923 Ję d r z e J Paszkiewicz ABSTRACT. The aim of the article is to show the role of the Balkan states within the Greek foreign policy dur- ing the period 1918–1923, on the base of diplomatic correspondence and historiography. The consequences of the military conflict with Turkey (1918–1922) and the internal problems, constantly harassing the socio-politi- cal life of Greece, seriously weakened its ability to impact effectively on particular geopolitical problems in the Balkan region. The Greek regional policy could be achieved, completely or partially, only with close cooperation with the powers from outside. It was connected with such cases as the delimitation of the Albanian frontier or the solution of the Western Thrace question in 1920. On the other hand, the proceedings of the Greek diplomats were determined by the belief that due to the unresolved territorial and national controversies, especially in the issue of the Macedonian and Thracian lands, the particular Balkan states were dependent on each other on the in- ternational arena. That is why the Greek diplomacy started to apply the tactics of balance of power in the region, aiming at the creation of more or less stable bilateral political constructions with the Kingdom SCS (Yugoslavia) and Romania. Their aim was to ensure the advantage over the competitors on the Balkan arena, especially over Bulgarian and Turkish revisionist agendas. STRESZCZENIE. Wyzwania dla bezpieczeństwa narodowego Grecji wobec zmian geopolitycznych na Bałkanach po I wojnie światowej (1919–1923) Celem artykułu jest ukazanie roli regionu bałkańskiego w greckiej politce zagranicznej w latach 1918–1923, na podstawie korespondencji dyplomatycznej i literatury przedmiotu. -

Wikipedia's History of Bulgaria

Wikipedia's History of Bulgaria • First Bulgarian Empire in 681 dominated most of the Balkans in the 9th-10th centuries and functioned as a Slavic cultural hub. • After a period of Byzantine rule (1018- 1185), the Second Bulgarian Empire emerged and lasted until 1396 • This was followed by 500 years of Ottoman Rule aka “Turkish yoke” Read: Under the Yoke by Ivan Vazov • A national rebellion (April Uprising) fails in 1876 , but Russians succeed in Russo-Turkish War freeing Bulgaria 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War) • The Treaty of San Stefano was signed on March 3, 1878, setting up an de jure autonomous Bulgarian principality on the territories of the Second Bulgarian Empire (see previous slide). • The Great Powers immediately rejected the treaty out of fear that such a large country in the Balkans might threaten their interests. The subsequent Treaty of Berlin (July 13, • 1878) split Bulgaria in two. Map of Treaty of Berlin: • This played a significant role in Bulgaria is split in two – forming Bulgaria's militaristic Bulgaria and Eastern approach to foreign affairs during the first half of the 20th century. Roumelia • Treaty of San Stefano March 3, 1878 (black out-line) • Treaty of San Stefano March 3, 1878 • Congress of Berlin (July 13, 1878) split Bulgaria in two Eastern Rumelia • After a bloodless revolution on 6 September 1885, Eastern Rumelia was annexed by the Principality of Bulgaria, which was de jure a tributary state but de facto functioned as independent nation. • After the Bulgarian victory in the subsequent Serbo- Bulgarian War, the status quo was recognized by the Tophane Agreement on 24 March 1886. -

Mathematics Without Borders - Autumn 2019 Group 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - AUTUMN 2019 GROUP 2 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abanilla, Alaina Cassandra P. Philippines Batangas Province 2 Certificate 2 Abduazimova Jasmina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 3 Abduazizona Robiya Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 4 Abdulfattah Parhiz Afghanistan Herat 2 Certificate 5 Abdulhakim Nurlanbek Uulu Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 2 Certificate 6 Abdumazhidov Nodirbek Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 7 Abdurahmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 8 Abduraufov Zafar Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Bronze 9 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 2 Bronze 10 Abdusattorov Abdullox Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 11 Abdusattorova Shakhzoda Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 12 Abdushukurova Oysha Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 13 Abduvahobov Abduvahob Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 14 Abduvakhidov Bakhtiyornur Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Bronze 15 Abelado, Theo Sebastian A. Philippines Naga City 2 Bronze 16 Abrorova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 17 Achelia Hasan Ismail Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 18 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 19 Adaliya Kalinova Stoilova Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 20 Adam Genadievich Burmistrov Bulgaria Burgas 2 Certificate 21 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 2 Bronze 22 Adam Mohamed Sabri Mohamed Mahmud Bulgaria Smolyan 2 Certificate 23 Adel Ivaylova Kamenova Bulgaria Kyustendil 2 Certificate 24 Adeli Nikolova Boyadzhieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 25 Adelina Encheva Stoianova Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 26 Adelina -

The Genie from Washington, DC, Goes Global: Master of Obscurity (M

Chapter 8 The Genie from Washington, DC, Goes Global: Master of Obscurity (M. O.) he genie has accommodated the strategies, methods and Trhetoric of the Bolshevik communist Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov to the motives of Washington, DC and the current White House. However, he expanded his “vision” to advising far right parties in Europe and boosting ultra-right political movements across that continent, citing as great examples sim- Figure 27.1. ilar campaigns in the nineteen thirties. He has advocated the embrace of racism. His proposals lack any details. Their mean- ing and required explanations are provided herein. A list of far right parties, established in the nineteen thirties, which includ- ed racism as an integral part of their programs, included: 1. Austria: Deutsche Nationalsozialistische Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP) (Figure 27.1.). Figure 27.2. 2. Belgium: Rexist Party (Figure 27.2.). 3. Belgium: Vlaams Nationaal Verbond (Figure 27.3.). 4. Belgium: Deutsch-Vlämische Arbeitsgemeinschaft (Figure 27.4.). Figure 27.3. 5. Bulgaria: Bulgarian National Socialist Workers Party (Figure 27.5.). 263 Protected by Muslims During World War II Figure 27.4. Figure 27.5. Figure 27.6. Figure 27.7. Figure 27.8. Figure 27.9. Figure 27.10. Figure 27.11. Figure 27.12. Figure 27.13. Figure 27.14. Figure 27.15. Figure 27.16. Figure 27.17. Figure 27.18. Figure 27.19. Figure 27.20. 264 The Genie from Washington, DC, Goes Global Figure 27.21. Figure 27.22. Figure 27.23. Figure 27.24. Figure 27.25. Figure 27.26. Figure 27.27. Figure 27.28. Figure 27.29.