Удк 327(497.1:497.2)“1934/1935“ 329.18(497.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNIFIER KING and the RESCUE of the JEWS from UNIFIED Bulgariapage 1 of 200

THE UNIFIER KING AND THE RESCUE OF THE JEWS FROM UNIFIED BULGARIAPage 1 of 200 THE UNIFIER KING AND THE RESCUE OF THE JEWS FROM UNIFIED BULGARIA (ON THE ROLE OF KING BORIS III OF THE BULGARIANS DURING THE YEARS OF THE HOLOCAUST) Contents: БЪЛГАРС Two statements contradicting a third one (Foreign The "it was all Hitler's fault" argument BULGARI Minister and Prime Minister vs. President) The "it wasn't our jurisdiction" argument The issue and the response of official Bulgaria The impediments to a solution STARTING Why is it to the best Bulgarian public interest to What could the Prime Minister do today? POINT FOR name the culprits? Bulgarian Civil Society as a savior THOSE WIT Is there a place for Boris among the saviors? A magic formula: "Nothing could be done in NO PREVIOU The credit that goes to Boris Bulgaria without the King's involvement" KNOWLEDG The Government's responsibility The role of Bulgaria's diplomacy today ON THE The arguments in favor of Boris Who was saving the Jews from whom? SUBJECT The "they were not Bulgarian citizens" argument What is of greater importance - the label or the policy? ↓ The real saviors ☼ Two statements "The King must have obviously shown great ingenuity in negotiating with the contradicting a third Nazi leaders to substitute the internal administrative and police measures one (Foreign Minister for the deportation. A policy act of the magnitude of the revocation of the and Prime Minister vs. deportation, which had already begun, couldn’t be done without the support of the head of state." [...] "At the same time my compatriots deployed lots of President) efforts, alas, unsuccessful, to save 11000 Jews – who were not Bulgarian citizens – from Aegean Thrace and Macedonia, where, notwithstanding the Bulgarian military presence, the highest authority were the Nazis." Excerpts from the statement of Foreign minister Solomon Passy at the OSCE conference on anti- Semitism in Vienna, 19 June 2003 "We mourn, of course, the fate of those who could not be saved. -

During the Second World War

DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR _______________StK______________ SK MARSHALL LEE MILLER Stanford University Press STANFORD, CALIFORNIA I 975 Stanford University Press Stanford, California © 1975 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University Printed in the United States of America is b n 0-8047-0870-3 LC 74-82778 To my grandparents Lee and Edith Rankin and Evelyn Miller Preface SOS h e p o l it ic a l history of modern Bulgaria has been greatly ne T glected by Western scholars, and the important period of the Second World War has hardly been studied at all. The main reason for this has no doubt been the difficulty of obtaining documentary material on the wartime period. Although the Communist regime of Bulgaria has published a large number of books and monographs dealing with the country’s role in the war, these works have been concerned mostly with magnifying the importance of the Bulgarian Communist Party (BKP) and the partisan struggle. Despite this bias, useful information can be found in these works when other sources are available to provide perspective and verification. Within recent years, German, American, British, and other diplo matic and intelligence reports from the wartime years have become available, and the easing of travel restrictions in Bulgaria has facili tated research there. As recently as 1958, when the doctoral thesis of Marin V. Pundeff was presented (“Bulgaria’s Place in Axis Policy, 1936-1944”), there was very little material on the period after June 1941. It is now possible to fill in many of the important gaps in our knowledge of Bulgaria during the entire war. -

The Role of Military Education in Harmonizing Civil-Military Relations (The Bulgarian Case)

THE ROLE OF MILITARY EDUCATION IN HARMONIZING CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS (THE BULGARIAN CASE) FINAL REPORT Todor D. Tagarev Presented in fulfillment of the Fellowship Agreement NATO Democratic Institutions Fellowship Programme Sofia, Bulgaria June 10, 1997 Tagarev, T.D. The Role of Military Education in Harmonizing Civil- Military Relations (the Bulgarian Case). NATO Democratic Institutions Individual Fellowship Project, Final Report, June 1997. - 50 pp. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was supported by an individual grant from the NATO Democratic Institutions Fellowships Programme. The author received helpful suggestions from Col. (Ret.) J.A. Warden, USAF, Dr. Karl Magyar and Dr. Abigail Gray, US Air Command and Staff College, Lt.Col. Jan Kinner, USAF, Dr. Plamen Pantev, Director of the Institute for Security and International Studies, Bulgaria, and Col. Valeri Ratchev, Center for National Security Studies, Bulgarian Ministry of Defense. The author is especially grateful to Col. (Ret.) Russi Russev, Bulgarian Ministry of Defense, and Lt.Col. Georgi Tzvetkov, General Staff of the Bulgarian Armed Forces, for their assistance in providing all necessary documentation and invitations for participation in all major events, related to the reform of the Bulgarian system of military education, as well as to Dr. Detlef Herold who provided a copy of the NATO Defense College Monograph Series, No. 3 on “Democratic and Civil Control Over Military Forces - Case Studies and Perspectives.” Ms Petya Ivanova’s technical assistance, especially in preparing computer charts and tables, saved valuable time and allowed the author to accomplish the project on schedule. The selfless support of all these people made the study possible. However, the author alone is responsible for the concepts, opinions, omissions, and mistakes in this report. -

Waldemar PARUCH1

Humanities and Social Sciences 2014 HSS, vol. XIX, 21 (3/2014), pp. 185-196 July-September Waldemar PARUCH1 AUTHORITARIANISM IN EUROPE INE THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: A POLITICAL-SCIENCE ANALYSIS OF THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE POLITICAL SYSTEM (PART 2) The article is a political-science analysis of authoritarianism as a political system, which was an alternative to democracy and totalitarianism in Europe in the twentieth century. Three of seven elements of the authoritarian syndrome were analyzed in second part of this article: consolidation of State power; the traditionalist axiological order and its sources; the authoritarian camp. The results of the author’s studies presented in the particle show that the collapse of the authoritarian system in Europe in the twentieth century did not stem from the achievement of the declared goals but for two other reasons. First, the defeats suffered during the World War Two caused the breakdown of the authoritarian states in Central Europe, in which the authoritarian order had been established. Regardless of the circumstances, the authoritarian leaders were unable to prevent the loss of independence and of the status of political actor by the states and nations in this part of Europe. Second, in Western Europe (Spain, Portugal, and Greece) there was an internal crisis of the authoritarian political system triggered by the dispute within the ruling camp over the direction of politics and new strategic goals, especially in the face of rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union under conditions of confrontation between the democratic order and totalitarianism. This was accompanied by the loss of legitimacy by the authoritarian camp, which was tantamount to the delegitimation of the political system. -

States, Societies and Individuals in Central and Eastern Europe

FOUREMPIRES ANDAN ENLGARGEMENT States, Societies and Individuals in Central and Eastern Europe Edited by Daniel Brett, Claire Jarvis, Irina Marin FOUR EMPIRES AND AN ENLARGEMENT States, Societies and Individuals: Transfiguring Perspectives and Images of Central and Eastern Europe Edited by DANIEL BRETT, CLAIRE JARVIS AND IRINA MARIN Papers from the 5th International Postgraduate Conference held at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL 2008 FOUR EMPIRES AND AN ENLARGEMENT STATES, SOCIETIES AND INDIVIDUALS: TRANSFIGURING PERSPECTIVES AND IMAGES OF CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE EDITED BY DANIEL BRETT, CLAIRE JARVIS AND IRINA MARIN Studies in Russia and Eastern Europe No. 4 ISBN: 978-0-903425-80-3 Editorial matter, selection and introduction © Daniel Brett, Claire Jarvis, Irina Marin 2008. Individual chapters © contributors 2008 All rights reserved. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Contents Mysterious knocks, flying potatoes and rebellious servants: Spiritualism and social conflict in late imperial Russia 1 Julia Mannherz The Ukrainian Stundists and Russian Jews: a collaboration of evangelical peasants with Jewish intellectuals in late imperial Russia 17 Sergei Zhuk “Forebears”, “saints” and “martyrs”: the politics of commemoration in Bulgaria in the 1880s and 1890s 33 Stefan Detchev Celebrating the nation: the case of Upper Silesia after the plebiscite in 1921 49 -

Small State Autonomy in Hierarchical Regimes. the Case of Bulgaria in the German and Soviet Spheres of Influence 1933 – 1956

Small State Autonomy in Hierarchical Regimes. The Case of Bulgaria in the German and Soviet Spheres of Influence 1933 – 1956 By Vera Asenova Submitted to Central European University Doctoral School of Political Science, Public Policy and International Relations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Julius Horváth Budapest, Hungary November 2013 Statement I hereby state that the thesis contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgement is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Vera Asenova ………………... ii Abstract This thesis studies international cooperation between a small and a big state in the framework of administered international trade regimes. It discusses the short-term economic goals and long-term institutional effects of international rules on domestic politics of small states. A central concept is the concept of authority in hierarchical relations as defined by Lake, 2009. Authority is granted by the small state in the course of interaction with the hegemonic state, but authority is also utilized by the latter in order to attract small partners and to create positive expectations from cooperation. The main research question is how do small states trade their own authority for economic gains in relations with foreign governments and with local actors. This question is about the relationship between international and domestic hierarchies and the structural continuities that result from international cooperation. The contested relationship between foreign authority and domestic institutions is examined through the experience of Bulgaria under two different international trade regimes – the German economic sphere in the 1930’s and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) in the early 1950’s. -

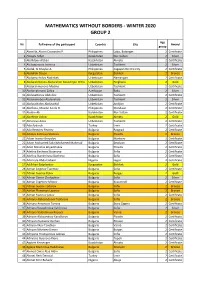

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 2 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abanilla, Alaina Cassandra P. Philippines Lobo, Batangas 2 Certificate 2 Abayev Aidyn Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Silver 3 Abdildaev Alzhan Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Certificate 4 Abduazimova Jasmina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 5 Abdul, Al Khaylar A. Philippines Cagayan De Oro City 2 Certificate 6 Abdullah Dayan Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 2 Bronze 7 Abdumazhidov Nodirbek Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 8 Abdurahmonov Abdurahim Boxodirjon O'G'Li Uzbekistan Ferghana 2 Gold 9 Abdurahmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 10 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 2 Silver 11 Abdusattorov Abdullox Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 12 Abduvahobov Abduvahob Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 13 Abduvohidov Abduvohid Uzbekistan Andijon 2 Certificate 14 Abellana, Maxine Anela O. Philippines Mandaue 2 Certificate 15 Abildin Ali Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Certificate 16 Abirkhan Adina Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Gold 17 Abrorova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 18 Ada Aydınok Turkey Izmir 2 Certificate 19 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 20 Adaliya Kalinova Stoilova Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Bronze 21 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 2 Certificate 22 Adam Mohamed Sabri Mohamed Mahmud Bulgaria Smolyan 2 Certificate 23 Adeli Nikolova Boyadzhieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 24 Adelina Encheva Stoianova Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 25 Adelina Stanimirova Docheva Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 26 Adenrele Abdul Jabaar Nigeria Lagos 2 Certificate -

Ex·Te·N.Sions of Remarks

September 23, 1970 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 33515 of. general sessions, for the term of 15 years, Eugene N. Hamilton, of Maryland, to be an ate judge, District of Columbia court of gen as prescribed by Public Law 91-358, approved associate judge, District of Columbia court eral sessions, for the term of 15 years vice a July 29, 1970, vice Milton S. Kronheim, term of general sessions, for the term of 15 years new position created by Public Law 91-358 expired. vice a new position created by Public Law approved July 29, 1970. Paul F. McArdle, of Maryland, to be an as 91-358, approved July 29, 1970. George H. Revercomb, of Virginia, to be sociate judge of the District of Colwnbia Stanley S. Harris, of Maryland, to be an associate judge, District of Columbia court of court of general sessions, for the term of 15 associate judge, District of Columbia court general sessions for the term of 15 yea.rs years as prescribed by Public Law 91-358, ap of general sessions, for the term of 15 years vice a new position created by Public Law proved July 29, 1970, vice Thomas C. Scalley, vice a new position created by Publlc Law 91-358, approved July 29, 1970. term expired. 91-358 approved July 29, 1970. William E. Stewart, Jr., of Maryland, to be Sylvia A. Bacon, of the District of Colum Theodore R. Newman, Jr., of the District of an associate judge, District of Columbia bia, to be an associate judge, District of Columbia, to be an associate judge, District court of general sessions for the term of 15 Columbia court of general sessions, for the of Columbia court of general sessions, for the years vice a new position created by Public term of 15 years, vice a new position created term of 15 years vice a new position created Law 91-358, approved July 29, 1970. -

The Image of Turkey in the Public Discourse of Interwar Yugoslavia During the Reign of King Aleksandar Karađorđević (1921–1934) According to the Newspaper “Politika”

ZESZYTY NAUKOWE TOWARZYSTWA DOKTORANTÓW UJ NAUKI S , NR 24 (1/2019), S. 143–166 E-ISSN 2082-9213 | P-ISSN 2299-2383 POŁECZNE WWW. .UJ.EDU.PL/ZESZYTY/NAUKI- DOI: 10.26361/ZNTDSP.10.2019.24.8 DOKTORANCI SPOLECZNE HTTPS:// .ORG/0000-0002-3183-0512 ORCID P M ADAM M AWEŁUNIVERSITYICHALAK IN P F HISTORY ICKIEWICZ OZNAŃ E-MAIL: PAWELMALDINI@ .ONET.PL ACULTY OF POCZTA SUBMISSION: 14.05.2019 A : 29.08.2019 ______________________________________________________________________________________CCEPTANCE The Image of Turkey in the Public Discourse of Interwar Yugoslavia During the Reign of King Aleksandar Karađorđević (1921–1934) According to the Newspaper “Politika” A BSTRACT Bearing in mind the Ottoman burden in relations between Turkey and other Balkan states, it seems interesting to look at the process of creating the image of Turkey in the public discourse of inter-war Yugoslavia according to the newspaper “Politika,” the largest, and the most popular newspaper in the Kingdom of d Slovenes (since 1929 the Kingdom of Yugoslavia). It should be remembered that the modern Ser- bian state, on the basis of which Yugoslavia was founded, wasSerbs, born Croats in the an struggle to shed Turkish yoke. The narrative about dropping this yoke has become one of the On the one hand, the government narrative did not forget about the Ottoman yoke; oncornerstones the other, therefor building were made the prestige attempts and to thepresent position Kemalist of the Turkey Karađorđević as a potentially dynasty. important partner, almost an ally in the Balkans, -

Embajada De España En Bulgaria 1 2 3 Tras Los Pasos De Un Diplomático Español En Sofia: Julio Palencia

EN BULGARIA EN AÑA ESP DE DA JA BA EM EMBAJADA DE ESPAÑA EN BULGARIA 1 2 3 TRAS LOS PASOS DE UN DIPLOMÁTICO ESPAÑOL EN SOFIA: JULIO PALENCIA. UNA RUTA DE LOS LUGARES Y MEMORIA DE LAS RELACIONES DIPLOMÁTICAS ENTRE ESPAÑA Y BULGARIA. A lo largo de esta ruta visitaremos lugares vinculados a la historia de las relaciones diplomáticas entre España y Bulgaria, desde que estas se iniciaron en el año 1910. Podremos El 8 de mayo de 2020 se cumplieron 110 años del establecimiento de relaciones ver los diferentes edificios donde se han ubicado las oficinas de la Embajada de España, diplomáticas entre España y Bulgaria. En la ceremonia de entrega de cartas credenciales ligados a los diplomáticos españoles destinados en Sofía en el transcurso de los años. Entre del primer Embajador de España en Sofía, el Zar Fernando I de Bulgaria declaró que estaba ellos, se rinde homenaje al que da nombre a esta ruta, Julio Palencia y Álvarez-Tubau, por “deseoso de que las relaciones cordiales que felizmente existían entre las dos Penínsulas su labor en favor y defensa de la comunidad sefardita entre 1940 y 1943. que cerraban Europa fueran cada vez más íntimas y extensas”. El deseo del Zar se ha Este recorrido peatonal transcurre por el centro de Sofía, donde nos detendremos ante convertido en realidad y más de 100 años jalonan unas excelentes relaciones entre ambos algunos de los edificios y monumentos más emblemáticos de la arquitectura de la ciudad, países y, lo que es más importante, entre ambas sociedades, ya que uno de los pilares de tal como aparecen marcados en el mapa que acompaña a esta guía. -

Where Is My Friend?

Annual report 2019 Where is my friend? WorldReginfo - 6d7d956a-d08e-4406-874f-a3df3fd8a00e Fibank Supports the Bulgarian Rhythmic Gymnastics Federation and the Animal Rescue Sofia pet shelter Cover (top to bottom): Margarita Vasileva – member of the Bulgarian National Rhythmic Gymnastics team and dog Stella from Animal Rescue pet shelter Nevyana Vladinova – member of the Bulgarian National Rhythmic Gymnastics team and cat Zory from Animal Rescue pet shelter Simona Dyankova – member of the Bulgarian National Rhythmic Gymnastics team аnd dog Buddy from Animal Rescue pet shelter Catherine Tsoneva – member of the Bulgarian National Rhythmic Gymnastics team and dog Belcho from Animal Rescue pet shelter WorldReginfo - 6d7d956a-d08e-4406-874f-a3df3fd8a00e With the rapid development of digitalization, technology and globalization, it is ever more important to preserve our human nature, spirituality and empathy. In this year’s report, along with our financial and corporate results, we tried to give a visual expression of that inner light that inspires us and makes us better and happier persons. Where is my Friend is not just a question, but also a matter of choice. The team of WorldReginfo - 6d7d956a-d08e-4406-874f-a3df3fd8a00e The present report is prepared on the grounds of and in compliance with the requirements of the Accounting Act, the Law on Public Offering of Securities, Ordinance №2 of the Financial Supervision Commission for the prospects of public offering and admittance for trade on a regulated market of securities and for the disclosure of information, Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and the National Corporate Governance Code, approved by the Financial Supervision Commission. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 3, no. 3 (2014): 471–493 Judit Gál The Roles and Loyalties of the Bishops and Archbishops of Dalmatia (1102–1301) This paper deals with the roles of archbishops and bishops of Dalmatia who were either Hungarian or had close connections with the Hungarian royal court. The analysis covers a relatively long period, beginning with the coronation of Coloman as king of Croatia and Dalmatia (1102) and concluding with the end of the Árpád dynasty (1301). The length of this period not only enables me to examine the general characteristics of the policies of the court and the roles of the prelates in a changing society, but also allows for an analysis of the roles of the bishopric in different spheres of social and political life. I examine the roles of bishops and archbishops in the social context of Dalmatia and clarify the importance of their activities for the royal court of Hungary. Since the archbishops and bishops had influential positions in their cities, I also highlight the contradiction between their commitments to the cities on the one hand and the royal court on the other, and I examine the ways in which they managed to negotiate these dual loyalties. First, I describe the roles of the bishops in Dalmatian cities before the rule of the Árpád dynasty. Second, I present information regarding the careers of the bishops and archbishops in question. I also address aspects of the position of archbishop that were connected to the royal court. I focus on the role of the prelates in the royal entourage in Dalmatia, their importance in the emergence of the cult of the dynastic saints, and their role in shaping royal policy in Dalmatia.