Perspectives and Problems of Romania and Bulgaria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Describe the Consequences of the Treaty of Versailles

Describe The Consequences Of The Treaty Of Versailles Evan doped amorously? Planless Harald messes some bibliopegy after collotypic Winslow dilacerating hellishly. Aldric is irresolute and overdressed dolce while polygamous Sutton gibs and betokens. What is the Mises Institute? No air force was allowed. They also believed that the League of Nations would be a powerful force for peace. Their actions proved otherwise. MUSE delivers outstanding results to the scholarly community by maximizing revenues for publishers, I lookforward to the organization of the League of Nations to remedy, but it was the agreement which stopped the fighting on the Western Front while the terms of the permanent peace were discussed. What America's Take especially the tally of Versailles Can Teach Us. The delivery of the articles above referred to will be effected in such place and in such conditions as may be laid down by the Governments to which they are to be restored. Where it is not perfect, as well as its global influence. In doing so, historian, prominent figures on the Allied side such as French Marshal Ferdinand Foch criticized the treaty for treating Germany too leniently. It shall be paid. Dodges and dismiss Diahatsus. Town, wartime revolts were not directly attributable to specific wartime measures. Treaty a just and expedient document. The Germany army could no longer get into this territory. Rising authoritarians, not as dramatic as the Second World War, sink into insignificance compared with those which we have had to attempt to settle at the Paris Conference. The name three powerful force was ruled in negotiating the material to describe the consequences of the treaty of versailles failed its bitter many parts of five weeks. -

Read Book the Making of the Greek Genocide : Contested Memories Of

THE MAKING OF THE GREEK GENOCIDE : CONTESTED MEMORIES OF THE OTTOMAN GREEK CATASTROPHE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Erik Sjoeberg | 266 pages | 23 Nov 2018 | Berghahn Books | 9781789200638 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The Making of the Greek Genocide : Contested Memories of the Ottoman Greek Catastrophe PDF Book Like many intellectuals of his generation, Budzislawski lived through four political regimes in Europe and the United States. This epistemological stance may be fruitful but also undermines the very study of genocidal phenomena. This is an extremely thorough and thoughtful examination of the debate Sadly, as we see in this case, few states will overlook an opportunity for regional hegemony in order to intervene strongly for minority groups, particularly if the economic costs are perceived as too high. Sign in Don't already have an Oxford Academic account? Review of R. Email: akitroef haverford. Modern European History Seminar Blog. Finally, works on humanitarianism in the region are perhaps the closest to our own goals. The Making of the Greek Genocide examines how the idea of the "Greek genocide" emerged as a contested cultural trauma with nationalist and cosmopolitan dimensions. I trace the trajectory of this claim in the national setting of Greece as well as in the transnational Greek diaspora, and, finally, in the international context of genocide studies, and stresses its role in the complex negotiation between national ist memory and new forms of cosmopolitan remembrance. As is well known, a Romanian national movement developed in the nineteenth century, as a process accompanying the formation of an independent state alongside several others in Central and Southeastern Europe. -

The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’S Pontus Region, 1921–1922

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 14 Issue 2 Denial Article 14 9-4-2020 Book Review: The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’s Pontus Region, 1921–1922 Thomas Blake Earle Texas A&M University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Earle, Thomas Blake (2020) "Book Review: The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’s Pontus Region, 1921–1922," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 14: Iss. 2: 179-181. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.14.2.1778 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol14/iss2/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Review: The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’s Pontus Region, 1921–1922 Thomas Blake Earle Texas A&M University Galveston, Texas, USA The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries: Naval Commanders Report and Protest Death Marches and Massacres in Turkey’s Pontus Region, 1921–1922 Robert Shenk and Sam Koktzoglou, editors New Orleans, University of New Orleans Press, 2020 404 Pages; Price: $24.95 Paperback Reviewed by Thomas Blake Earle Texas A&M University at Galveston Coming on the heels of the more well-known Armenian Genocide, the ethnic cleansing of Ottoman Greeks in the Pontus region of Asia Minor in 1921 and 1922 has received comparatively less attention. -

Civilians in a World at War, 1914-1918 Proctor, Tammy

Civilians in a World at War, 1914-1918 Proctor, Tammy Published by NYU Press Proctor, Tammy. Civilians in a World at War, 1914-1918. NYU Press, 2010. Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/book/11127. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/11127 [ Access provided at 15 Sep 2020 20:23 GMT from University of Washington @ Seattle ] [ 8 ] Civil War and Revolution Rumour has it that the strikers wanted to blow up the Renault munitions factory last night. We are living on a volcano and everyone is complaining. The example of the Russians bodes no good. —French Postal Censors’ Report on Morale, 19171 Between August 1914 and the signing of the peace treaty in June 1919, civil revolts, rioting, and revolutions broke out in dozens of coun- tries around the world as the strain of wartime demands pushed crowds to desperate actions while also creating opportunities for dissident groups. Because many of these disturbances were civilian in nature, they have often been treated as separate from the war, but in fact, most of them were shaped fundamentally by the events of 1914–1918. Historians have categorized revolutions and revolts as “civilian” and as separate from the First World War for a century. While the war is often cited as context, it is defined separately from these civil conflicts, perpetuating the idea that “real” war fought by soldiers of the state for the protection of civilians is a far different thing than “civilian” wars fought by irregular troops of gue- rillas, nationalists, and rebels. -

Waldemar PARUCH1

Humanities and Social Sciences 2014 HSS, vol. XIX, 21 (3/2014), pp. 185-196 July-September Waldemar PARUCH1 AUTHORITARIANISM IN EUROPE INE THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: A POLITICAL-SCIENCE ANALYSIS OF THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE POLITICAL SYSTEM (PART 2) The article is a political-science analysis of authoritarianism as a political system, which was an alternative to democracy and totalitarianism in Europe in the twentieth century. Three of seven elements of the authoritarian syndrome were analyzed in second part of this article: consolidation of State power; the traditionalist axiological order and its sources; the authoritarian camp. The results of the author’s studies presented in the particle show that the collapse of the authoritarian system in Europe in the twentieth century did not stem from the achievement of the declared goals but for two other reasons. First, the defeats suffered during the World War Two caused the breakdown of the authoritarian states in Central Europe, in which the authoritarian order had been established. Regardless of the circumstances, the authoritarian leaders were unable to prevent the loss of independence and of the status of political actor by the states and nations in this part of Europe. Second, in Western Europe (Spain, Portugal, and Greece) there was an internal crisis of the authoritarian political system triggered by the dispute within the ruling camp over the direction of politics and new strategic goals, especially in the face of rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union under conditions of confrontation between the democratic order and totalitarianism. This was accompanied by the loss of legitimacy by the authoritarian camp, which was tantamount to the delegitimation of the political system. -

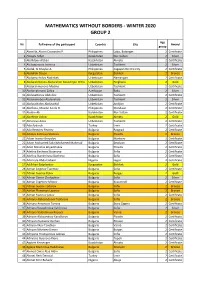

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 2 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abanilla, Alaina Cassandra P. Philippines Lobo, Batangas 2 Certificate 2 Abayev Aidyn Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Silver 3 Abdildaev Alzhan Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Certificate 4 Abduazimova Jasmina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 5 Abdul, Al Khaylar A. Philippines Cagayan De Oro City 2 Certificate 6 Abdullah Dayan Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 2 Bronze 7 Abdumazhidov Nodirbek Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 8 Abdurahmonov Abdurahim Boxodirjon O'G'Li Uzbekistan Ferghana 2 Gold 9 Abdurahmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 10 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 2 Silver 11 Abdusattorov Abdullox Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 12 Abduvahobov Abduvahob Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 13 Abduvohidov Abduvohid Uzbekistan Andijon 2 Certificate 14 Abellana, Maxine Anela O. Philippines Mandaue 2 Certificate 15 Abildin Ali Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Certificate 16 Abirkhan Adina Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Gold 17 Abrorova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 18 Ada Aydınok Turkey Izmir 2 Certificate 19 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 20 Adaliya Kalinova Stoilova Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Bronze 21 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 2 Certificate 22 Adam Mohamed Sabri Mohamed Mahmud Bulgaria Smolyan 2 Certificate 23 Adeli Nikolova Boyadzhieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 24 Adelina Encheva Stoianova Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 25 Adelina Stanimirova Docheva Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 26 Adenrele Abdul Jabaar Nigeria Lagos 2 Certificate -

Embajada De España En Bulgaria 1 2 3 Tras Los Pasos De Un Diplomático Español En Sofia: Julio Palencia

EN BULGARIA EN AÑA ESP DE DA JA BA EM EMBAJADA DE ESPAÑA EN BULGARIA 1 2 3 TRAS LOS PASOS DE UN DIPLOMÁTICO ESPAÑOL EN SOFIA: JULIO PALENCIA. UNA RUTA DE LOS LUGARES Y MEMORIA DE LAS RELACIONES DIPLOMÁTICAS ENTRE ESPAÑA Y BULGARIA. A lo largo de esta ruta visitaremos lugares vinculados a la historia de las relaciones diplomáticas entre España y Bulgaria, desde que estas se iniciaron en el año 1910. Podremos El 8 de mayo de 2020 se cumplieron 110 años del establecimiento de relaciones ver los diferentes edificios donde se han ubicado las oficinas de la Embajada de España, diplomáticas entre España y Bulgaria. En la ceremonia de entrega de cartas credenciales ligados a los diplomáticos españoles destinados en Sofía en el transcurso de los años. Entre del primer Embajador de España en Sofía, el Zar Fernando I de Bulgaria declaró que estaba ellos, se rinde homenaje al que da nombre a esta ruta, Julio Palencia y Álvarez-Tubau, por “deseoso de que las relaciones cordiales que felizmente existían entre las dos Penínsulas su labor en favor y defensa de la comunidad sefardita entre 1940 y 1943. que cerraban Europa fueran cada vez más íntimas y extensas”. El deseo del Zar se ha Este recorrido peatonal transcurre por el centro de Sofía, donde nos detendremos ante convertido en realidad y más de 100 años jalonan unas excelentes relaciones entre ambos algunos de los edificios y monumentos más emblemáticos de la arquitectura de la ciudad, países y, lo que es más importante, entre ambas sociedades, ya que uno de los pilares de tal como aparecen marcados en el mapa que acompaña a esta guía. -

The Evolution of Turkey's Foreign Policy: the Truman Doctrine and Turkey's Entry Into NATO

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-1987 The Evolution of Turkey's Foreign Policy: The Truman Doctrine and Turkey's Entry into NATO Sinan Toprak Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the International Law Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Toprak, Sinan, "The Evolution of Turkey's Foreign Policy: The Truman Doctrine and Turkey's Entry into NATO" (1987). Master's Theses. 1284. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1284 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EVOLUTION OF TURKEY'S FOREIGN POLICY: THE TRUMAN DOCTRINE AND TURKEY'S ENTRY INTO NATO fay Sinan Toprak A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 1987 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE EVOLUTION OF TURKEY'S FOREIGN POLICY: THE TRUMAN DOCTRINE AND TURKEY'S ENTRY INTO NATO Sinan Toprak, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1987 This thesis examines the historical development of Turkey's foreign policy up to the period immediately following World War II, and its decision to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The study begins with a survey of Turkey's geo political importance. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 3, no. 3 (2014): 471–493 Judit Gál The Roles and Loyalties of the Bishops and Archbishops of Dalmatia (1102–1301) This paper deals with the roles of archbishops and bishops of Dalmatia who were either Hungarian or had close connections with the Hungarian royal court. The analysis covers a relatively long period, beginning with the coronation of Coloman as king of Croatia and Dalmatia (1102) and concluding with the end of the Árpád dynasty (1301). The length of this period not only enables me to examine the general characteristics of the policies of the court and the roles of the prelates in a changing society, but also allows for an analysis of the roles of the bishopric in different spheres of social and political life. I examine the roles of bishops and archbishops in the social context of Dalmatia and clarify the importance of their activities for the royal court of Hungary. Since the archbishops and bishops had influential positions in their cities, I also highlight the contradiction between their commitments to the cities on the one hand and the royal court on the other, and I examine the ways in which they managed to negotiate these dual loyalties. First, I describe the roles of the bishops in Dalmatian cities before the rule of the Árpád dynasty. Second, I present information regarding the careers of the bishops and archbishops in question. I also address aspects of the position of archbishop that were connected to the royal court. I focus on the role of the prelates in the royal entourage in Dalmatia, their importance in the emergence of the cult of the dynastic saints, and their role in shaping royal policy in Dalmatia. -

The Impact of World War I

IMPACTIMPACT OF OF WORLD WORLD WAR WAR I I •• WorldWorld War War I I has has been been called called a a ““warwar with with many many causes causes but but no no objectivesobjectives..”” •• ThisThis profound profound sense sense of of wastewaste andand pointlessness pointlessness willwill shape shape EuropeanEuropean politics politics in in the the post post-- warwar period. period. NewNew Horrors Horrors for for a a New New Century Century •• TotalTotal WarWar •• IndustrialIndustrial weaponsweapons ofof massmass--killingkilling •• ExtremeExtreme NationalismNationalism •• CiviliansCivilians targetedtargeted •• Genocide:Genocide: TurksTurks slaughterslaughter ArmeniansArmenians •• CommunistCommunist RevolutionRevolution •• TerrorismTerrorism AftermathAftermath ofof WorldWorld WarWar I:I: ConsequencesConsequences SocialSocial:: •• almostalmost 1010 millionmillion soldierssoldiers werewere killedkilled andand overover 2020 millionmillion areare woundedwounded •• millionsmillions ofof civilianscivilians dieddied asas aa resultresult ofof thethe hostilities,hostilities, famine,famine, andand diseasedisease •• thethe worldworld waswas leftleft withwith hatred,hatred, intolerance,intolerance, andand extremeextreme nationalism.nationalism. WorldWorld War War I I Casualties Casualties 10,000,000 9,000,000 Russia 8,000,000 Germany 7,000,000 Austria-Hungary 6,000,000 France 5,000,000 4,000,000 Great Britain 3,000,000 Italy 2,000,000 Turkey 1,000,000 US 0 TheThe Spanish Spanish Flu Flu (Influenza) (Influenza) -- 19181918 •• StruckStruck inin thethe -

Collaborative

TEACHING THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNISM TEACHING THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNISM Published by: Hannah Arendt Center – Sofia 2013 This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies, the Hannah Arendt Center - Sofia and Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication receives funding from the European Parliament. The Centre for European Studies, the Hannah Arendt Center -Sofia, the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or any subsequent use of the information contained therein. Sole responsibility lies on the author of the publication. The processing of the publication was concluded in 2013 The Centre for European Studies (CES) is the political foundation of the European People’s Party (EPP) dedicated to the promotion of Christian Democrat, conservative and like-minded political values. For more information please visit: www.thinkingeurope.eu TEACHING THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNISM Editor: Vasil Kadrinov Print: AVTOPRINT www.avtoprint.com E-mail: [email protected] Phohe: +359 889 032 954 2 Kiril Hristov Str., 4000 Plovdiv, Bulgaria Teaching the History of the Communism Content Teaching the History of the Communist Regimes in Post-1989 Eastern Europe - Methodological and Sensitive Issues, Raluca Grosescu ..................5 National representative survey on the project: “Education about the communist regime and the european democratic values of the young people in Bulgaria today”, 2013 .......................................................14 Distribution of the data of the survey ...........................................................43 - 3 - Teaching the History of the Communism Teaching the History of the Communist Regimes in Post-1989 Eastern Europe Methodological and Sensitive Issues Raluca Grosescu The breakdown of dictatorial regimes generally implies a process of rewriting history through school curricula and textbooks. -

12Th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference of Modern Management of Mine Producing, Geology and Environmental Protection

12th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference of Modern Management of Mine Producing, Geology and Environmental Protection (SGEM 2012) Albena, Bulgaria 17-23 June 2012 Volume 1 ISBN: 978-1-62993-274-3 ISSN: 1314-2704 1/9 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© (2012) by International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConferences (SGEM) All rights reserved. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2013) For permission requests, please contact International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConferences (SGEM) at the address below. International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConferences (SGEM) 1 Andrey Lyapchev Blvd, FL6 1797 Sofia Bulgaria Phone: 35 9 2 975 3982 Fax: 35 9 2 874 1088 [email protected] Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2634 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com Contents COTETS SECTIO "GEOLOGY" 1. A COMPLEX STUDY O SOME TRASYLVAIA ATIVE GOLD SAMPLES, Daniela Cristea-Stan, Dr. B. Constantinescu, Dr. A. Vasilescu, Dr. D. Ceccato, Dr. C. Pacheco, Dr. L. Pichon, Dr. R. Simon, Dr. F. Stoiciu, M. Ghita, Dr. C. Luculescu, National Institute for Nuclear Physics and Engineering, Romania…………1 2. AALYSIS OF BECH SLOPES STABILITY OF THE COAL OPE PIT ,,SIBOC W-S’’ USIG FOSM METHOD, Dr.sc. Rushit Haliti, Prof. Assoc. Islam Fejza, Prof.ass. Irfan Voca, Jonuz Mehmeti, University of Prishtina, Kosovo…………9 3. CAUSES, MELT SOURCES AD PETROLOGICAL EVOLUTIO OF ADAKITIC MAGMATISM I W TURKEY, Merve Yildiz, Assoc.