Xviii I Introduction Studies, Whose Stately White Marble Building Is One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

124900176.Pdf

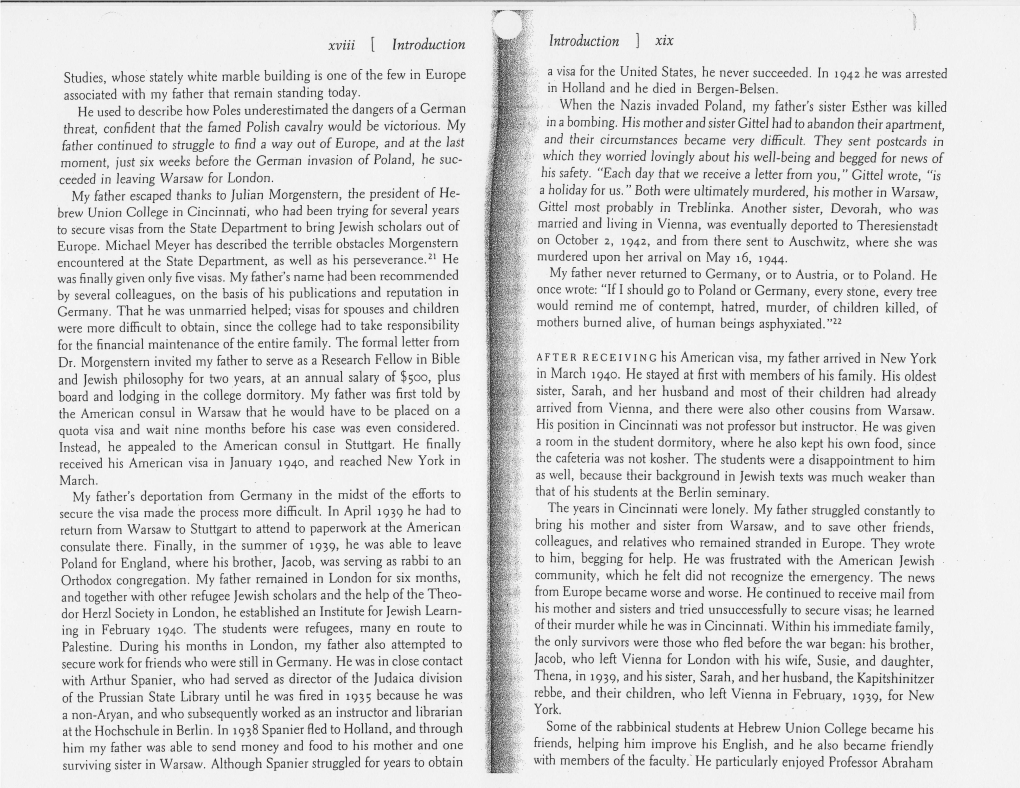

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

Personal Material

1 MS 377 A3059 Papers of William Frankel Personal material Papers, correspondence and memorabilia 1/1/1 A photocopy of a handwritten copy of the Sinaist, 1929; 1929-2004 Some correspondence between Terence Prittie and Isaiah Berlin; JPR newsletters and papers regarding a celebration dinner in honour of Frankel; Correspondence; Frankel’s ID card from a conference; A printed article by Frankel 1/1/2 A letter from Frankel’s mother; 1936-64 Frankel’s initial correspondence with the American Jewish Committee; Correspondence from Neville Laski; Some papers in Hebrew; Papers concerning B’nai B’rith and Professor Sir Percy Winfield; Frankel’s BA Law degree certificate 1/1/3 Photographs; 1937-2002 Postcards from Vienna to I.Frankel, 1937; A newspaper cutting about Frankel’s meeting with Einstein, 2000; A booklet about resettlement in California; Notes of conversations between Frankel and Golda Meir, Abba Eban and Dr. Adenauer; Correspondence about Frankel’s letter to The Times on Shylock; An article on Petticoat lane and about London’s East End; Notes from a speech on the Jewish Chronicle’s 120th anniversary dinner; Notes for speech on Israel’s prime ministers; Papers concerning post-WW2 Jewish education 1/1/4 JPR newsletters; 1938-2006 Notes on Harold Wilson and 1974 General Election; Notes on and correspondence with Oswald Mosley, 1966 Correspondence including with Isaiah Berlin, Joseph Leftwich, Dr Louis Rabinowitz, Raphael Lowe, Wolfe Kelman, A.Krausz, Norman Cohen and Dr. E.Golombok 1/1/5 Printed and published articles by Frankel; 1939, 1959-92 Typescripts, some annotated, for talks and regarding travels; Correspondence including with Lord Boothby; MS 377 2 A3059 Records of conversations with Dr. -

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1 UNITED STATES Organizations are listed according to functions as follows: Religious, Educational 305 Cultural 299 Community Relations 295 Overseas Aid 302 Social Welfare 323 Social, Mutual Benefit 321 Zionist and Pro-Israel 326 Note also cross-references under these headings: Professional Associations 334 Women's Organizations 334 Youth and Student Organizations 335 COMMUNITY RELATIONS Gutman. Applies Jewish values of justice and humanity to the Arab-Israel conflict in AMERICAN COUNCIL FOR JUDAISM (1943). the Middle East; rejects nationality attach- 307 Fifth Ave., Suite 1006, N.Y.C., 10016. ment of Jews, particularly American Jews, (212)889-1313. Pres. Clarence L. Cole- to the State of Israel as self-segregating, man, Jr.; Sec. Alan V. Stone. Seeks to ad- inconsistent with American constitutional vance the universal principles of a Judaism concepts of individual citizenship and sep- free of nationalism, and the national, civic, aration of church and state, and as being a cultural, and social integration into Ameri- principal obstacle to Middle East peace, can institutions of Americans of Jewish Report. faith. Issues of the American Council for Judaism; Special Interest Report AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (1906). In- stitute of Human Relations, 165 E. 56 St., AMERICAN JEWISH ALTERNATIVES TO N.Y.C., 10022. (212)751-4000. Pres. May- ZIONISM, INC. (1968). 133 E. 73 St., nard I. Wishner; Exec. V. Pres. Bertram H. N.Y.C., 10021. (212)628-2727. Pres. Gold. Seeks to prevent infraction of civil Elmer Berger; V. Pres. Mrs. Arthur and religious rights of Jews in any part of 'The information in this directory is based on replies to questionnaires circulated by the editors. -

(I) the Five Jewish Influences on Ramah

THE JACOB RADER MARCUS CENTER OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES MS-831: Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation Records, 1980–2008. Series C: Council for Initiatives in Jewish Education (CIJE). 1988–2003. Subseries 5: Communication, Publications, and Research Papers, 1991–2003. Box Folder 42 2 Fox, Seymour, and William Novak. Vision at the Heart. Planning and drafts, February 1996-May 1996. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org FROM: "Dan Pekarsky", INTERNET:[email protected] TO: Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 DATE: 2/5/96 10:19 AM Re: Ramah and my paper Sender: [email protected] Received: from audumla.students.wisc.edu (students.wisc.edu [144.92.104.66]) by dub-img-4.compuserve.com (8.6.10/5.950515) id JAA22229; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 09:56:41 -0500 Received: from mail.soemadison.wisc.edu by audumla.students.wisc.edu; id IAA111626 ; 8.6.9W/42; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 08:56:40 -0600 From: "Dan Pekarsky" <[email protected]> Reply-To: [email protected] To: [email protected], [email protected] Date: Sun, 04 Feb 1996 21 :12:00 -600 Subject: Ramah and my paper X-Gateway: iGate, (WP Office) vers 4.04m - 1032 MIME-Version: 1.0 Message-Id: <[email protected]> Content-Type: TEXT/PLAIN; Charset=US-ASCII Content-Transfer-Encoding: ?BIT Nessa, I am finding the in-progress Ramah piece very interesting, and I'm struck by the number of times my own intuitive reactions are mirrored a few lines down by your own comments in the brackets. -

Ordination of the 100Th Graduate of the Israeli Rabbinical Program

power, in print, broadcast, and social media, Israel is a country awash with ORDINATION “ and in hospital rooms and family moments. rabbis. What difference can one They provide leadership, solace, support, OF THE hundred more make? A great difference. and vision. They are part of a remarkable We find graduates of HUC-JIR’s Israeli movement of Jewish renewal currently Rabbinical Program at some of the most 100TH unfolding - alongside all the challenges and significant settings within Israeli society. conflicts - in contemporary Israel. From the GRADUATE OF They serve as leaders in informal and border with Lebanon to the shores of the Red formal education; as school principals THE ISRAELI Sea, in makeshift structures and impressive and directors of early childhood education edifices, this first one hundred is preparing RABBINICAL systems. They run large institutions, and the groundwork for the hundreds to follow bring congregations to life around Israel. PROGRAM in their illustrious footsteps. They have Their voices are heard in the corridors of established congregations and institutions, ISRAELI RABBINICAL PROGRAM: In the Footsteps of “My classmates grew up secular, 11 Generations Orthodox, or religious Reform, are of different ages and from different places of Rabbis in Israel, but found their center in Reform ideology. I value the connection RABBI LEORA with the North American students EZRAHI-VERED ’17 worshipping and studying with us. It is very meaningful to form friendships with colleagues who will be leaders throughout Israel and around the world, so that our communities will one day EDUCATION: ■ Granddaughter of Rabbi Wolfe Kelman, become friends too.” B.A. -

CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM: Volume XVIII, Number 1, Fall 1963 Published by the Rabbinical Assembly. EDITOR: Samuel H. Dresner. DEPARTM

TO sigh Oo1 to h the able AU, the ham Yaw prec CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM: Volume XVIII, Number 1, Fall 1963 Published by The Rabbinical Assembly. Sha~ a fe EDITOR: Samuel H. Dresner. to '" MANAGING EDITOR: jules Harlow. con' BOOK REVIEW EDITOR: jack Riemer. focu wen DEPARTMENT EDITORS: Max Routtenberg, David Silvennan. peri EDITORIAL BOARD: Theodore Friedman, Chairman; Walter Ackerman, Philip A rian, Solomon Bernards, Ben Zion Bokser, Seymour Fox, Shamai Kanter, fron Abraham Karp, Wolfe Kelman, jacob Neusner, Fritz Rothschild, Richard sent Rubenstein, 1\Jurray Schiff, Seymour Siegel, Andre Ungar, Mordecai Waxman, the Max Wahlberg. to o hap] of tl OFFICERS OF THE RABBINICAL ASSEMBLY: Rabbi Theodore Friedman, President; Rabbi Max j. Routtenberg, Vice-President; Rabbi S. Gershon Levi, Treas men urer; Rabbi Seymour j. Cohen, Recording Secretary; Rabbi jacob Kraft, hose Corresponding Secretary; Rabbi Max D. Davidson, Comptroller; Rabbi Wolfe cons Kelman, Executive Vice-President. wha gard pres• CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM is a quarterly publication. The subscription fee is $3.00 per year. Application for second class mail privileges is pending at New York, SIOn N.Y. All articles and communications should be addressed to the Editor, Andr 979 Street, Springfield, Mass.; subscriptions to The Rabbinical 3080 Broadway, New York 27, N.Y. TO BIRMINGHAM, AND BACK ANDRE UNGAR THERE WAS no special emphasis in the way that group of Jews murmured, sighed, chanted its way through the ancient benediction of "Blessed are You, 0 our eternal God, Who help a man walk uprightly," but perhaps there ought to have been. It was, to all appearances, a simple case of morning worship; the stylish dining room in which it took place presented a rather unremark able setting for the occasion. -

Directories, Lists, Necrology (1982)

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1 UNITED STATES Organizations are listed according to functions as follows: Religious, Educational 303 Cultural 297 Community Relations 293 Overseas Aid 301 Social Welfare 321 Social, Mutual Benefit 319 Zionist and Pro-Israel 325 Note also cross-references under these headings: Professional Associations 332 Women's Organizations 333 Youth and Student Organizations 334 COMMUNITY RELATIONS Gutman. Applies Jewish values of justice and humanity to the Arab-Israel conflict in AMERICAN COUNCIL FOR JUDAISM (1943). the Middle East; rejects nationality attach- 307 Fifth Ave., Suite 1006, N.Y.C., 10016. ment of Jews, particularly American Jews, (212)889-1313. Pres. Clarence L. Cole- to the State of Israel as self-segregating, man, Jr.; Sec. Alan V. Stone. Seeks to ad- inconsistent with American constitutional vance the universal principles of a Judaism concepts of individual citizenship and sep- free of nationalism, and the national, civic, aration of church and state, and as being a cultural, and social integration into Amen- principal obstacle to Middle East peace, can institutions of Americans of Jewish Report. faith. Issues of the American Council for Judaism; Special Interest Report. AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (1906). In- stitute of Human Relations, 165 E. 56 St., AMERICAN JEWISH ALTERNATIVES TO N.Y.C., 10022. (212)751-4000. Pres. May- ZIONISM, INC. (1968). 133 E. 73 St., nard I. Wishner; Exec. V. Pres. Bertram H. N.Y.C., 10021. (212)628-2727. Pres. Gold. Seeks to prevent infraction of civil Elmer Berger; V. Pres. Mrs. Arthur and religious rights of Jews in any part of 'The information in this directory is based on replies to questionnaires circulated by the editors. -

Thinking About Women

SHALOM HARTMAN INSTITUTE A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATION • • CONVERSATION JEWISH OF JOURNAL A A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATION Number 5 / Summer 2010 / $7.95 Number 5 / Summer 2010 • • 2010 Summer / 5 Number Thinking About SHALOM HARTMAN INSTITUTE HARTMAN SHALOM Women HAVRUTA A Journal of Jewish Conversation Table of Contents Number 5 / Summer 2010 Editor A Letter to our Readers ............................................. 2 Stuart Schoffman Associate Editors Thinking about Women ............................................. 4 Laura Major Feminism and Jewish Tradition Orr Scharf A Symposium Editorial Advisory Board Breaking the Silence ................................................. 28 Bill Berk Women’s Voices and Men’s Anxieties Alfredo Borodowski Ariel Picard By Channa Pinchasi Rachel Sabath- Beit Halachmi Dror Yinon Leah’s Prayers: A Feminist Reading .......................... 36 Noam Zion By Noam Zion Graphic Design Studio Rami & Jaki Jewish Poetry and the Feminist Imagination ............. 46 Cover photograph by Bruce Damonte The Gifts of Muriel Rukeyser By Laura Major From Silence to Empowerment ............................... 54 Women Reading Women in the Talmud Seder Nashim: A Women’s Beit Midrash Divine Qualities and Real Women .............................. 62 The Feminine Image in Kabbalah By Biti Roi Who is In and Who is Out.......................................... 70 The Two Voices of Ruth By Orit Avnery Published by the Shalom Hartman Institute, Jerusalem Afikoman /// Old Texts for New Times Contact us: “Without Regard -

22992/RA Indexes

INDEX of the PROCEEDINGS of THE RABBINICAL ASSEMBLY ❦ INDEX of the PROCEEDINGS of THE RABBINICAL ASSEMBLY ❦ Volumes 1–62 1927–2000 Annette Muffs Botnick Copyright © 2006 by The Rabbinical Assembly ISBN 0-916219-35-6 All rights reserved. No part of the text may be reproduced in any form, nor may any page be photographed and reproduced, without written permission of the publisher. Manufactured in the United States of America Designed by G&H SOHO, Inc. CONTENTS Preface . vii Subject Index . 1 Author Index . 193 Book Reviews . 303 v PREFACE The goal of this cumulative index is two-fold. It is to serve as an historical reference to the conventions of the Rabbinical Assembly and to the statements, thoughts, and dreams of the leaders of the Conser- vative movement. It is also to provide newer members of the Rabbinical Assembly, and all readers, with insights into questions, problems, and situations today that are often reminiscent of or have a basis in the past. The entries are arranged chronologically within each author’s listing. The authors are arranged alphabetically. I’ve tried to incorporate as many individuals who spoke on a subject as possible, as well as included prefaces, content notes, and appendices. Indices generally do not contain page references to these entries, and I readily admit that it isn’t the professional form. However, because these indices are cumulative, I felt that they were, in a sense, an historical set of records of the growth of the Conservative movement through the twentieth century, and that pro- fessional indexers will forgive these lapses. -

Orthodox Objection to the Lieberman Clause Atara Kelman

Orthodox Objection to the Lieberman Clause Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University May 6, 2020 Atara Kelman Mentor: Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Acknowledgements נשמת כל חי תברך את שמך ה׳ אלוקינו בכל עת צרה וצוקה אין לנו מלך אלא אתה As I work on this project during the COVID-19 pandemic, I recognize that the stability that I have felt my whole life is a mirage, and that our vulnerability is ever present. At the same time, I understand that I am fortunate and blessed with good health, a caring family, and emotional and economic security. These feelings are more prominent during this time of crises, but have been the hallmark of my life. At the culmination of the Honors Program, I am appreciative for opportunities the Honors Program has provided for me, with both intensive academic classes and cultural opportunities. Stern College served as my base for two years of learning and growing, and for that I am grateful. Rabbi Ezra Schwartz served as my mentor for this project, after teaching me for the majority of my time in Stern College. I am indebted to him for his suggestions, references, and commitment to helping me learn. A large portion of my research was stimulated by conversations with Rabbi Saul Berman, whose insight and integrity is inspiring. Most of all, this would not have been possible without the help of my family. My interest in such a topic certainly grew from conversations at home, and my family serves as the best editorial board. -

PLAIN TALK Speak at Mizrachi Religious Activities Soulh East Conference by Allred Segal Convention Division Miami Beach November 4-5 to \ MR

AN INDEPENDENT WEEKLY SERVING AMERICAN CITIZENS OF JEWISH FAITH THE OLDEST AND MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED JEWISH PUBLICATION IN THIS TERRITORY JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA, VOL. 27 NO. 38 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 13, 1950 $3.00 A YEAR Moshe Sharett to Heads JWB's Regional in PLAIN TALK Speak at Mizrachi Religious Activities Soulh East Conference By Allred Segal Convention Division Miami Beach November 4-5 to \ MR. SOLOMON'S CHILDREN Mr. Hyman Solomon of 3437 ATLANTIC CITY, N. J., Discuss Emigration Problems Street, Inglewood, Cal- West 82nd Moshe Sharett, Foreign Minister ifornia, has been thinking much Israel, the princi- about his children as Jews. Which, of will deliver More than 300 representatives of Jewish communities throughout of course, is what most Jewish pal address of the keynote session the South Eastern United States will meet in Miami Beach, Fla., parents think about all the time: of Mizrachi Women’s Silver Ju- November 4 and 5, to discuss current assistance to Jewish survivors How should we raise that kid bilee Convention, when the emigrating to Israel, the United States and other lands, as well as Jewishly. impress Should we religious-Zionist women’s con- + the integration of thousands of former deeply on his mind the fact that v' I DP's into American life. Sunday The occasion will combined he is Jewish? That is, should we clave starts here this be a regional sponsored by educate him to make much of his night. conference are Daniel Ruskin, of Miami / the Joint Distribution Committee, being Jewish? Or should we let p; : :-x:x > Beach, outstanding U. -

1983 35 02 00.Pdf

Volume XXXV November, 1983 Number 2 American Jewish Archives A Journal Devoted to the Preservation and Study of the American Jewish Experience Jacob Rader Marcus, Ph.D., Editor Abraham J. Peck, Ph.M., Associate Editor Published by The American Jewish Archives on the Cincinnati Campus of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion Dr. Alfred Gottschalk, President American lewish Archives is indexed in The Index to lewish Periodicals, Current Contents, The American Historical Review, United States Political Science Documents, and The journal of American History. Information for Contributors: American lewish Archives follows generally the University of Chicago Press "Manual of Style" (12th revised edition) and "Words into Type" (3rd edition), but issues its otun style sheet which may be obtained by writing to: The Associate Editor, American lezuish Archives 3 101 Clifton Avenue Cincinnati, Ohio 4jzzo Patrons 1983: The Neumann Memorial Publication Fund The Harris and Eliza Kempner Fund Published by The American lewish Archives on the Cincinnati campus of the Hebretu Union College-lewish Institute of Religion ISSN ooz-po~X Or983 by the American jezuish Archives Contents 90 Editorial Note 91 Introduction Jonathan D. Sarna I00 Resisters and Accommodators: Varieties of Orthodox Rabbis in America, I 8 86-1983 Jeffrey S. Gurock 188 The Conservative Rabbi-"Dissatisfied But Not Unhappy" Abraham J. Karp 263 The Changing and the Constant in the Reform Rabbinate David Polish 342 Book Reviews Ravitch, Diane, and Goodenow, Ronald K., Edited by. Educating an Urban People: The New York City Experience Reviewed by Stephan E Brurnberg 348 Friess, Horace L. Felix Adler and Ethical Culture: Memories and Studies (edited by Fannia Weingartner) Reviewed by Benny Kraut 3 52 Geipel, John.