The University of Chicago Teyku: the Insoluble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinuch’= Religious Education of Jewish Children and Youngsters

‘Chinuch’= Religious Education of Jewish Children and Youngsters Prof. Rabbi Ahron Daum teaches his youngest daughter Hadassah Yemima to kindle the Chanukah-lights during a family vacation to Israel, 1997 1 ‘Chinuch’ =Jewish Religious Education of Children Including: Preparation Program for ‘Giyur’ of Children: Age 3 – 18 1. ‘Chinuch’ definition: The Festival of Chanukah probably introduced the word “Chinuch” to Judaism. This means to introduce the child to Judaism and to dedicate and inaugurate him in the practice of ‘Mitzvot’. The parents, both mother and father, are the most important persons in the Jewish religious education of the child. The duty of religious education already starts during the period of pregnancy. Then the child is shaped and we should influence this process by not speaking ugly words, shouting, listening to bad music etc, but shaping it in a quiet, peaceful and harmonious atmosphere. After being born, the child already starts its first steps with “kashrut” by being fed with mother’s milk or with kosher baby formula. 2 The Midrash states that when the Jewish people stood at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah, they were asked by G-d for a guarantee that they would indeed observe the Torah in the future. The only security which God was willing to accept, concludes the Midrash, was the children of the Jewish people. This highlights the overwhelming significance of ‘Chinuch’. The duty to train children in ‘Mitzvah’-observance is rabbinic in nature. Parents are rabbinic ally obligated to make sure that their children observe the Torah, so that they will be accustomed to doing this when they reach the age of adulthood. -

Shatnez in Turkish Talleisim: What Happened and the Lessons to Be Learned Interview with Rabbi Yosef Sayagh

Article written by the Yated Ne’eman 3 Adar 5769, Feb 27th ‘09 Shatnez in Turkish Talleisim: What Happened and the Lessons to Be Learned Interview With Rabbi Yosef Sayagh Recently, a significant number of ‘Turkish’ talleisim made in Tunisia were found to contain shatnez, while yet others were found not be 100% wool. When this first came to light, not all the details were clear and we were advised to refrain from reporting the story until all the facts emerged. We sat down with Rabbi Yosef Sayagh of the Lakewood Shatnez Laboratory, who provided background information, as well as some of the relevant halachic details, regarding the recent find. • • • • • Yated: Can you provide a basic background of what was found and which talleisim are/were affected? Rabbi Sayagh: The only talleisim, which are an issue, are ‘Turkishe’talleisim. First let us briefly discuss the history of Turkishetalleisim. Turkishe talleisim have been made from wool that comes from Turkey. The reason why, historically,Chassidim have used talleisim with Turkish wool is because Turkey was a country that was known not to have any linen. Thus, if there was no linen around, the wool was obviously pure ofshatnez, and for that reason they preferred to use talleisim made of Turkish wool. The Belzer Rebbe, the Sar Shalom, was quoted as saying that after thechurban Bais Hamikdosh, the maalos, the qualities, of the land of Eretz Yisroel, became dispersed to other areas of the world. The mountains, for example, went to Switzerland. Theshvach, quality, of wool, he said, went to Turkey. That is another reason why some Chassidim preferred to use Turkishe talleisim. -

124900176.Pdf

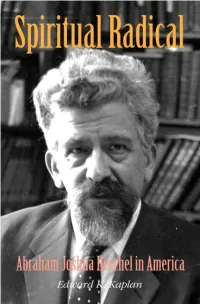

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

Defining Purity and Impurity Parshat Sh’Mini, Leviticus 6:1- 11:47| by Mark Greenspan “The Dietary Laws” by Rabbi Paul S

Defining Purity and Impurity Parshat Sh’mini, Leviticus 6:1- 11:47| by Mark Greenspan “The Dietary Laws” by Rabbi Paul S. Drazen, (pp.305-338) in The Observant Life Introduction A few weeks before Passover reports came in from the Middle East that a cloud of locust had descended upon Egypt mimicking the eighth plague of the Bible. When the wind shifted direction the plague of locust crossed over the border into Israel. There was great excitement in Israel when some rabbis announced that the species of locust that had invaded Israel were actually kosher! Offering various recipes Rabbi Natan Slifkin announced that there was no reason that Jews could not adopt the North African custom of eating the locust. Slifkin wrote: “I have eaten locusts on several occasions. They do not require a special form of slaughter and one usually kills them by dropping them into boiling water. They can be cooked in a variety of ways – lacking any particular culinary skills I usually just fry them with oil and some spices. It’s not the taste that is distinctive so much as the tactile experience of eating a bug – crunchy on the outside with a chewy center!” Our first reaction to the rabbi’s announcement is “Yuck!” Yet his point is well taken. While we might have a cultural aversion to locusts there is nothing specifically un-Jewish about eating them. The Torah speaks of purity and impurity with regard to food. Kashrut has little to do with hygiene, health, or culinary tastes. We are left to wonder what makes certain foods tamei and others tahor? What do we mean when we speak about purity with regard to kashrut? The Torah Connection These are the instructions (torah) concerning animals, birds, all living creatures that move in water and all creatures that swarm on earth, for distinguishing between the impure (tamei) and the pure (tahor), between living things that may be eaten and the living things that may not be eaten. -

Torah Portion Summary

PARASHAT BERESHEIT - BIRKAT HAHODESH October 6, 2007 – 24 Tishrei 5768 Annual: Genesis 1:1 – 6:8 (Etz Hayim, p. 3; Hertz p. 2) Triennial Cycle: Genesis 1:1 – 2:3 (Etz Hayim, p. 3; Hertz p. 2) Haftarah: Isaiah 42:5 – 43:10 (Etz Hayim, p. 36; Hertz p. 21) Prepared by Rabbi Joyce Newmark Teaneck, New Jersey Torah Portion Summary The Torah begins with God’s creation of the world – light, heaven and earth, the oceans and dry land, the heavenly bodies, plants, animals, and finally the first human beings – in six days. God then blesses the seventh day, Shabbat, the day of rest. The human beings are placed in the Garden of Eden “to till it and tend it,” but when Adam and Eve disobey God’s commandment and eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil they are expelled from the Garden. Eve gives birth to two sons. When they are grown Cain, the elder, kills his brother, Abel, and is punished by God. Adam and Eve have a third son, Seth, and the Torah relates the 10 generations from Adam to Noah. The parasha concludes with God’s sorrow over human wickedness. 1. Does "Torah" Mean "Law"? When God began to create heaven and earth – the earth being unformed and void, with darkness over the surface of the deep and a wind from God sweeping over the water – God said “let there be light,” and there was light. (Bereisheit 1:1-3) A. Rabbi Yitzhak said: It was only necessary to begin the Torah with “This month shall mark for you...” (Shemot 12:2), for this is the first mitzvah about which Israel was commanded. -

Guide '07 to a Shatnez-Free Home

Guide ‘07 To A Shatnez-Free Home INTRODUCTION This information is current only at the time of publication Frequently Asked Questions reinforcements used in their products. Because of z What types of clothing need Shatnez testing? this lack of information, even a shomer shabbos z Garments from which countries should I avoid? retailer or manufacturer cannot be relied upon to z Can I tell from the label if a garment is non- claim that his merchandise is Shatnez-free. This Shatnez? applies even though the clothing was manufactured especially for him, and even if he was present at the When shopping for clothing, the Jewish consumer factory during production. In addition, many wants to be sure that his purchase is Shatnez–free. retailers will falsely testify that a particular garment Unfortunately, the information generally available was tested and found non-Shatnez. All garments to the consumer is very limited and occasionally pre-tested by an authorized Shatnez laboratory will misleading. Outlined below are the sources of this carry an official label. information and an explanation of their inadequacies. Tailors and unqualified testers – There are some tailors and other people who claim to know Shatnez Content Labels – By Federal law, all garments are testing. While they may be familiar with the basic required to have a label listing the content of the elements of testing, they have not been trained in fabric. However, only the main shell fabric of the the complexities of garment construction and garment is included in this requirement. The content identification, and they do not keep up-to-date with of linings, reinforcements, and internal components the constant stream of new developments in the of the garment are not listed on the label. -

Personal Material

1 MS 377 A3059 Papers of William Frankel Personal material Papers, correspondence and memorabilia 1/1/1 A photocopy of a handwritten copy of the Sinaist, 1929; 1929-2004 Some correspondence between Terence Prittie and Isaiah Berlin; JPR newsletters and papers regarding a celebration dinner in honour of Frankel; Correspondence; Frankel’s ID card from a conference; A printed article by Frankel 1/1/2 A letter from Frankel’s mother; 1936-64 Frankel’s initial correspondence with the American Jewish Committee; Correspondence from Neville Laski; Some papers in Hebrew; Papers concerning B’nai B’rith and Professor Sir Percy Winfield; Frankel’s BA Law degree certificate 1/1/3 Photographs; 1937-2002 Postcards from Vienna to I.Frankel, 1937; A newspaper cutting about Frankel’s meeting with Einstein, 2000; A booklet about resettlement in California; Notes of conversations between Frankel and Golda Meir, Abba Eban and Dr. Adenauer; Correspondence about Frankel’s letter to The Times on Shylock; An article on Petticoat lane and about London’s East End; Notes from a speech on the Jewish Chronicle’s 120th anniversary dinner; Notes for speech on Israel’s prime ministers; Papers concerning post-WW2 Jewish education 1/1/4 JPR newsletters; 1938-2006 Notes on Harold Wilson and 1974 General Election; Notes on and correspondence with Oswald Mosley, 1966 Correspondence including with Isaiah Berlin, Joseph Leftwich, Dr Louis Rabinowitz, Raphael Lowe, Wolfe Kelman, A.Krausz, Norman Cohen and Dr. E.Golombok 1/1/5 Printed and published articles by Frankel; 1939, 1959-92 Typescripts, some annotated, for talks and regarding travels; Correspondence including with Lord Boothby; MS 377 2 A3059 Records of conversations with Dr. -

Spotlight On…..Shatnez Background: Parashat Tetzaveh Contains God's

Spotlight on…..Shatnez Background: Parashat Tetzaveh contains God’s instructions to Moshe for planning the Kohen Gadol’s garments. The Kohen Gadol wore multiple layered garments and elaborate accessories. In 28:6 the ephod (apron) is introduced: וְ ָע ׂ֖שּו ֶאת־ ָה ֵא ֹ֑פ ֹד ָ֠זָ ָהב ְת ֵ֨ ֵכ ֶלת וְַא ְרגָ ָ֜ ָמן תֹו ַַ֧ל ַעת ָש ִ֛ני וְ ֵֵׁ֥שש ָמ ְש ָׂ֖זר ַמ ֲע ֵֵׁ֥שה ח ֹ ֵ ֵֽׁשב׃ They shall make the ephod of gold, of blue, purple, and crimson wool, and of fine twisted linen, worked into designs. As this verse tells us, the ephod contained both wool and linen. This is quite surprising, because in Devarim the Torah prohibits wearing wool and linen together! This combination is referred to as shatnez. The prohibition against shatnez is a chok, which means a law from God that does not have a rational explanation. A midrash from Tanchuma offers one insight: Both Kayin and Hevel brought offerings to God. Hevel offered the finest of his wooly sheep, and Kayin offered flax seeds, the poorest of all his crops. God accepted Hevel’s offering and turned away from Kayin’s. Kayin sought to avenge what he felt was an injustice and killed his brother Hevel. Therefore, the midrash explains, God teaches us that it is not fitting to join the offering of Kayin, the sinner, with the offering of Hevel, the gracious one. And that is why we have the prohibition of shatnez. Questions: 1. Imagine that you are an Israelite during the time of the Beit HaMikdash. -

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1

Directories Lists Necrology National Jewish Organizations1 UNITED STATES Organizations are listed according to functions as follows: Religious, Educational 305 Cultural 299 Community Relations 295 Overseas Aid 302 Social Welfare 323 Social, Mutual Benefit 321 Zionist and Pro-Israel 326 Note also cross-references under these headings: Professional Associations 334 Women's Organizations 334 Youth and Student Organizations 335 COMMUNITY RELATIONS Gutman. Applies Jewish values of justice and humanity to the Arab-Israel conflict in AMERICAN COUNCIL FOR JUDAISM (1943). the Middle East; rejects nationality attach- 307 Fifth Ave., Suite 1006, N.Y.C., 10016. ment of Jews, particularly American Jews, (212)889-1313. Pres. Clarence L. Cole- to the State of Israel as self-segregating, man, Jr.; Sec. Alan V. Stone. Seeks to ad- inconsistent with American constitutional vance the universal principles of a Judaism concepts of individual citizenship and sep- free of nationalism, and the national, civic, aration of church and state, and as being a cultural, and social integration into Ameri- principal obstacle to Middle East peace, can institutions of Americans of Jewish Report. faith. Issues of the American Council for Judaism; Special Interest Report AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (1906). In- stitute of Human Relations, 165 E. 56 St., AMERICAN JEWISH ALTERNATIVES TO N.Y.C., 10022. (212)751-4000. Pres. May- ZIONISM, INC. (1968). 133 E. 73 St., nard I. Wishner; Exec. V. Pres. Bertram H. N.Y.C., 10021. (212)628-2727. Pres. Gold. Seeks to prevent infraction of civil Elmer Berger; V. Pres. Mrs. Arthur and religious rights of Jews in any part of 'The information in this directory is based on replies to questionnaires circulated by the editors. -

Acharei-Kedoshim Aliyah Summary

Acharei-Kedoshim Aliyah Summary General Overview: This week's reading, Acharei-Kedoshim, begins with a detailed description of the service of the High Priest on Yom Kippur. Dozens of commandments are then discussed in this week's reading. Among them: the prohibitions against offering sacrifices outside the Temple; consuming blood; incestuous, adulterous, or other forbidden relationships; various mandatory gifts for the poor; love for every Jew, prohibition against sorcery; honesty in business dealings; and sexual morality. First Aliyah: The High Priest is instructed to only enter the Holy of Holies chamber of the sanctuary once a year, on Yom Kippur; and even on this holiest day of the year, the entry into the Temple's inner sanctum must be accompanied by a special service and specific offerings which are detailed in this reading. The High Priest was only permitted to enter amidst a cloud of burning incense. Also, special white garments were worn by the High Priest on this day. While offering the day's sacrifices, the High Priest would "confess" on behalf of the entire nation, attaining atonement for the past year's sins. This section continues with a description of the "scapegoat" ceremony procedure. Second Aliyah: After concluding the order of the Yom Kippur service in the Temple, the Torah instructs us to observe Yom Kippur as a Day of Atonement when we must abstain from work and "afflict" ourselves. The Jews are then forbidden to offer sacrifices anywhere other than the Tabernacle or Temple. Third Aliyah: We are enjoined not to consume blood. When slaughtering fowl or undomesticated animals, we are commanded to cover their blood with earth. -

2011-Shatnez-Ami-Small.Pdf

48 AMI MAGAZINE // JANUARY 26, 2011 // 21 sh’vAT, 5771 CHECKING IN ON SHATNEZ There was a time when wearing shatnez, the forbidden mixture of wool and linen, was a forgotten mitzvah. Then, along came Rabbi Yosef Rosenberger, who used his two eyes to open all of ours. ARI GREENSPAN AND ARI Z. ZIVOTOFSKY Nearly 70 years ago, the world was introduced to Joseph Rosenberger, the unsung hero who single-handedly revolutionized the Torah world by introducing an awareness of this neglected mitzvah—and enabled us to avoid violating it. Today, shatnez laboratories, dry cleaner shatnez drop-offs and homemaker shatnez testers are commonplace. But we owe it all to Joseph Rosenberg. Several decades ago, the two of us decided to assist our neighbors by learning shatnez testing. The command post for such an endeavor was—and still is—THE Shatnez Lab, known officially as Mitzvoth-Good Deeds, Inc., at 203 Lee Ave in Brooklyn. 21 sh’vAT, 5771 // JANUARY 26, 2011 // AMI MAGAZINE 49 CHECKING IN ON SHATNEZ In post World War II America, the mitzvah of shatnez seemed to have been forgotten. A young refugee from Vienna, Austria—Rabbi Yosef Rosenberger—arrived in the United States in 1940, after surviving Dachau con- centration camp. His father had been in the clothing trade and preventing the issur (prohibition) of shat- nez became a burning passion for Rabbi Rosenberger. Despite being destitute and living in a refugee home, he saw a higher need and set out to fulfill it. He realized that hardly anyone was meticulous about shatnez. Even more frustrating for him, nobody really knew how to check for it. -

(I) the Five Jewish Influences on Ramah

THE JACOB RADER MARCUS CENTER OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES MS-831: Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation Records, 1980–2008. Series C: Council for Initiatives in Jewish Education (CIJE). 1988–2003. Subseries 5: Communication, Publications, and Research Papers, 1991–2003. Box Folder 42 2 Fox, Seymour, and William Novak. Vision at the Heart. Planning and drafts, February 1996-May 1996. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org FROM: "Dan Pekarsky", INTERNET:[email protected] TO: Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 Nessa Rapoport, 74671,3370 DATE: 2/5/96 10:19 AM Re: Ramah and my paper Sender: [email protected] Received: from audumla.students.wisc.edu (students.wisc.edu [144.92.104.66]) by dub-img-4.compuserve.com (8.6.10/5.950515) id JAA22229; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 09:56:41 -0500 Received: from mail.soemadison.wisc.edu by audumla.students.wisc.edu; id IAA111626 ; 8.6.9W/42; Mon, 5 Feb 1996 08:56:40 -0600 From: "Dan Pekarsky" <[email protected]> Reply-To: [email protected] To: [email protected], [email protected] Date: Sun, 04 Feb 1996 21 :12:00 -600 Subject: Ramah and my paper X-Gateway: iGate, (WP Office) vers 4.04m - 1032 MIME-Version: 1.0 Message-Id: <[email protected]> Content-Type: TEXT/PLAIN; Charset=US-ASCII Content-Transfer-Encoding: ?BIT Nessa, I am finding the in-progress Ramah piece very interesting, and I'm struck by the number of times my own intuitive reactions are mirrored a few lines down by your own comments in the brackets.