Global Climate Models Applied to Terrestrial Exoplanets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Arxiv:0809.1275V2

How eccentric orbital solutions can hide planetary systems in 2:1 resonant orbits Guillem Anglada-Escud´e1, Mercedes L´opez-Morales1,2, John E. Chambers1 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT The Doppler technique measures the reflex radial motion of a star induced by the presence of companions and is the most successful method to detect ex- oplanets. If several planets are present, their signals will appear combined in the radial motion of the star, leading to potential misinterpretations of the data. Specifically, two planets in 2:1 resonant orbits can mimic the signal of a sin- gle planet in an eccentric orbit. We quantify the implications of this statistical degeneracy for a representative sample of the reported single exoplanets with available datasets, finding that 1) around 35% percent of the published eccentric one-planet solutions are statistically indistinguishible from planetary systems in 2:1 orbital resonance, 2) another 40% cannot be statistically distinguished from a circular orbital solution and 3) planets with masses comparable to Earth could be hidden in known orbital solutions of eccentric super-Earths and Neptune mass planets. Subject headings: Exoplanets – Orbital dynamics – Planet detection – Doppler method arXiv:0809.1275v2 [astro-ph] 25 Nov 2009 Introduction Most of the +300 exoplanets found to date have been discovered using the Doppler tech- nique, which measures the reflex motion of the host star induced by the planets (Mayor & Queloz 1995; Marcy & Butler 1996). The diverse characteristics of these exoplanets are somewhat surprising. Many of them are similar in mass to Jupiter, but orbit much closer to their 1Carnegie Institution of Washington, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, 5241 Broad Branch Rd. -

Annual Report 2007 ESO

ESO European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere Annual Report 2007 ESO European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere Annual Report 2007 presented to the Council by the Director General Prof. Tim de Zeeuw ESO is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in the field of ground-based astronomy. It is supported by 13 countries: Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Further coun- tries have expressed interest in member- ship. Created in 1962, ESO provides state-of- the-art research facilities to European as- tronomers. In pursuit of this task, ESO’s activities cover a wide spectrum including the design and construction of world- class ground-based observational facili- ties for the member-state scientists, large telescope projects, design of inno- vative scientific instruments, developing new and advanced technologies, further- La Silla. ing European cooperation and carrying out European educational programmes. One of the most exciting features of the In 2007, about 1900 proposals were VLT is the possibility to use it as a giant made for the use of ESO telescopes and ESO operates the La Silla Paranal Ob- optical interferometer (VLT Interferometer more than 700 peer-reviewed papers servatory at several sites in the Atacama or VLTI). This is done by combining the based on data from ESO telescopes were Desert region of Chile. The first site is light from several of the telescopes, al- published. La Silla, a 2 400 m high mountain 600 km lowing astronomers to observe up to north of Santiago de Chile. -

Andrea Gróf Zsuzsa Horváth Exercises in Astronomy and Space

Andrea Gróf Zsuzsa Horváth Exercises in astronomy and space exploration for high school students ELTE DOCTORAL SCHOOL OF PHYSICS ANDREA GRÓF, ZSUZSA HORVÁTH EXOPLANETS AND SPACECRAFT Exercises in astronomy and space exploration for high school students ELTE DOCTORAL SCHOOL OF PHYSICS BUDAPEST 2021 The publication was supported by the Subject Pedagogical Research Programme of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Reviewers: József Kovács (astronomy), Ákos Szeidemann (didactics) Translation from Hungarian: Attila Salamon © Andrea Gróf, Zsuzsa Horváth ELTE Doctoral School of Physics Responsibe publisher: Dr. Jenő Gubicza Budapest 2021 2 Second, revised edition Compiled by: Andrea Gróf, Zsuzsa Horváth Professional proof-reader: Dr. József Kovács, ELTE Gothard Astrophysical Observatory The creation of the exercise book was supported by the Subject Pedagogical Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Table of contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction of exoplanets .......................................................................................... 5 DIMENSIONS AND DISTANCES ..................................................................................................... 5 THE HABITABLE ZONE OF EXOPLANETS, ................................................................................ -

UM ESTUDO SOBRE O Momentum ANGULAR

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E DA TERRA DEPARTAMENTO DE FÍSICA TEÓRICA E EXPERIMENTAL JULIANA CERQUEIRA DE SANTANA UM ESTUDO SOBRE O Momentum ANGULAR TOTAL DE ESTRELAS COM PLANETAS DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO NATAL, RN NOVEMBRO DE 2011 JULIANA CERQUEIRA DE SANTANA UM ESTUDO SOBRE O Momentum ANGULAR TOTAL DE ESTRELAS COM PLANETAS Trabalho apresentado ao Programa de Pós- graduação em Física do Departamento de Física Teórica e Experimental da UNIVER- SIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Física. Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Renan de Medeiros NATAL, RN NOVEMBRO DE 2011 Aos meus queridos pais Nilza e Roque, a quem eu tanto amo e que me inspiram a cada dia que acordo. ii Agradecimentos Assim como em nossa formação enquanto sujeito fomos orientados a agradecer por algum feito realizado em prol de nosso bem estar, nesse momento não é diferente. Agradeço a Deus, fonte de força espiritual, onde sempre busquei carregar minhas energias e toda esperança, pois o indivíduo não é feito só de razão. Agradeço aos meus pais Nilza e Roque, pelo seu amor in- condicional e por sua compreensão em todas minhas ausências. Ao professor José Renan pelos conhecimentos transmitidos e mais ainda que isso, pelos ensinamentos que ultrapassam as fron- teiras da Universidade. A sua figura de grande cientista que desperta o respeito e admiração de muitos. Aos meus irmãos Cida, Sérgio e André, que sempre me apoiaram em minhas esco- lhas. Agradeço ao professor Marildo pelo incentivo em todo momento da minha graduação, principalmente nos períodos iniciais deste curso. -

Efemeriszek Pontosítása Fedési Bolygórendszerekben

Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem Természettudományi Kar Csillagászati Tanszék Szakdolgozat Efemeriszek pontosítása fedési bolygórendszerekben Szerz®: Bakai Zoárd Témavezet®: Pál András Bels® konzulens: Érdi Bálint 2010 ENSIS D TIN E S E E Ö P T A V D Ö U S B . *F *. A T C A U . N LTAS SCI Tartalomjegyzék 1. Bevezetés 1 1.1. A kezdeti exobolygókutatás rövid története . 1 1.2. Közvetlen bolygó meggyelési módszerek . 2 1.3. Közvetett bolygó meggyelési módszerek . 2 1.4. Óriásbolygó vagy barna törpe? . 6 1.5. Fedési exobolygók jelent®sége . 7 1.6. Az els® neptunusztömeg¶ fedési exobolygó . 8 1.7. Szuper-Földek kutatása . 8 1.8. Exoholdak kutatása . 10 1.9. Exobolygókutatás fejl®dése, ¶rtávcsövek . 11 1.10. A jöv®ben tervezett ¶rprogramok . 13 1.11. Célkit¶zés . 15 2. A vizsgált fedési exobolygók 17 2.1. A TrES program . 17 2.2. Az XO program . 17 2.3. A HATNet program . 18 2.4. A vizsgált exobolygók . 18 3. Fotometriai meggyeléseink 27 3.1. A meggyelések . 27 3.2. Adatok feldolgozása . 28 4. Fénygörbe meghatározása 31 4.1. Szabad paraméterek meghatározása . 31 4.2. Szabad paraméterek illesztése . 34 4.3. Fénygörbe illesztése . 37 5. Összefoglalás 44 6. Kivonat 50 Köszönetnyilvánítás 51 Hivatkozások 52 1. Bevezetés Mint ismert Naprendszerünk egy csillagból és a körülötte Kepler-pályán közelít®leg egy síkban kering® nyolc bolygóból áll, így alkotva egy bolygórend- szert. Az Univerzumban ez a fajta rendszer mégsem a leggyakoribb, sokkal inkább jellemz®ek a kett®scsillagok, illetve a többes számú csillagrendsze- rek. A modern csillagászat megszületését®l szinte mindenki egyetértett azzal a hipotézissel, hogy Naprendszeren kívül is léteznek bolygók, de kutatásuk lehet®sége fel sem merült egészen a 19. -

Ralf Schoofs.Pdf

BILDAUSWAHL DER KÜNSTLER / FOTOGRAFEN BEI ASTROFOTO --- www.astrofoto.de --- Repräsentative Auswahl der erfolgreichsten Bilder (Farben unverbindlich). Die hier präsentierten Bilder dürfen nur für interne Layoutzwecke verwendet werden. Mit dem Downlaod ist keine Übertragung von Nutzungsrechten verbunden, diese müssen vor einer möglichen Nutzung eingeholt werden. Feindaten per Download / e-Mail / Leonardo Bildnummer: er001-100 Bildnummer: er001-107 Nachtseite der Erde, Erde bei Nacht, Erdkugel, Polarlichtoval Nachtseite der Erde, Polarlichtoval, Sonne, Sterne, Sternenhimmel (Illustration) (Illustration) © Ralf Schoofs © Astrofoto/Ralf Schoofs © Astrofoto/Ralf Schoofs Bildnummer: er001-108 Bildnummer: er001-109 Erdkugel (Satellitenfoto) vor Sternenhimmel (Illustration) Erdkugel, Erde, Nordamerika, Südamerika, Atlantik, Europa, Asien, © Astrofoto/Ralf Schoofs Nordpol (Satellitenfoto) vor Sternenhimmel (Illustration) © Ralf Schoofs © Astrofoto/Ralf Schoofs Copyright: © Astrofoto Astrofoto Inh. Bernd Koch e.K. Ihr persönlicher Ansprechpartner: Bernd Koch Hauptstr. 3A, D-57636 Sörth Kontakt: [email protected] Telefon +49-2681-983580 Fax: 983582 BILDAUSWAHL DER KÜNSTLER / FOTOGRAFEN BEI ASTROFOTO --- www.astrofoto.de --- Repräsentative Auswahl der erfolgreichsten Bilder (Farben unverbindlich). Die hier präsentierten Bilder dürfen nur für interne Layoutzwecke verwendet werden. Mit dem Downlaod ist keine Übertragung von Nutzungsrechten verbunden, diese müssen vor einer möglichen Nutzung eingeholt werden. Feindaten per Download / e-Mail / -

Tidal Locking

Tidal locking Tidal locking (also called gravitational locking or captured rotation) occurs when the long-term interaction between a pair of co-orbiting astronomical bodies drives the rotation rate of at least one of them into the state where there is no more net transfer of angular momentum between this body (e.g. a planet) and its orbit around the second body (e.g. a star); this condition of "no net transfer" must be satisfied over the course of one orbit around the second body.[1][2] This does not mean that the rotation and spin rates are always perfectly synchronized throughout an orbit, as there can be some Tidal locking results in the Moon rotating about its axis in about the same time it takes to orbitEarth . back and forth transfer over the course of an orbit. This effect arises Except for libration effects, this results in the Moon from the gravitational gradient (tidal force) between the co-orbiting keeping the same face turned toward Earth, as bodies, acting over a sufficiently long period of time. seen in the left figure. (The Moon is shown in polar view, and is not drawn to scale.) If the Moonwere In the special case where the orbital eccentricity and obliquity are not rotating at all, it would alternately show its near nearly zero, tidal locking results in one hemisphere of the revolving and far sides to Earth, while moving around Earth object constantly facing its partner, an effect known as synchronous in orbit, as shown in the right figure. rotation.[1][2][3] For example, the same side of the Moon always faces the Earth, although there is some libration because the Moon's orbit is not perfectly circular. -

Gliese 581D: a Possibly Habitable Planet Around a Red Dwarf Star

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 5, EPSC2010-417, 2010 European Planetary Science Congress 2010 c Author(s) 2010 Gliese 581d: A Possibly Habitable Planet around a Red Dwarf Star D. Schulze-Makuch (1), E.F. Guinan (2) (1) Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA ([email protected]) (2) Villanova University, Villanova, PA, USA ([email protected]) Abstract experienced on a planetary surface, beneficial for evolutionary innovations. Moreover, because of their Gliese 581d is a terrestrial super-earth planet, located low temperatures (~2200 – 3800 K), dM stars (unlike on the inside edge of the habitable zone away from hotter stars like our Sun at T ~5779 K) do not have its parent star. If Mars would be that size in our Solar significant photospheric Near UV (NUV) continuum System, Mars would likely be a habitable planet in a radiation below about 3000A. A more serious traditional sense (stability of liquid water on its concern is that many dM star HZ planets are likely to surface). The same is likely true for Gliese 581d, be tidally locked (with Prot = Porb), probably do not which makes it a promising candidate of the possess large moons, and many may be too old to be extrasolar planets detected so far to support life. enriched enough in metals to form a terrestrial type Planets around red dwarf stars (dM) appear in planet. Nevertheless, planets around older, less principle at least as suitable for the development of magnetically-active dM stars should be considered a life as planets around dG stars. prime target for possible life, and may also serve as a refuge for advanced, intelligent civilizations when 1. -

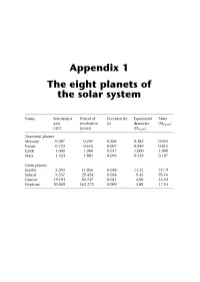

Appendix 1 the Eight Planets of the Solar System

Appendix 1 The eight planets of the solar system Name Semimajor Period of Eccentricity Equatorial Mass axis revolution ie) diameter (MEarth) (AU) (years) (DEarth) Terrestrial planets Mercury 0.387 0.241 0.206 0.382 0.055 Venus 0.723 0.615 0.007 0.949 0.815 Earth 1.000 1.000 0.017 1.000 1.000 Mars 1.524 1.881 0.093 0.532 0.107 Giant planets Jupiter 5.203 11.856 0.048 11.21 317.9 Saturn 9.537 29.424 0.054 9.45 95.16 Uranus 19.191 83.747 0.047 4.00 14.53 Neptune 30.069 163.273 0.009 3.88 17.14 Appendix 2 The first 200 extrasolar planets Name Mass Period Semimajor axis Eccentricity (Mj) (years) (AU) (e) 14 Her b 4.74 1,796.4 2.8 0.338 16 Cyg B b 1.69 798.938 1.67 0.67 2M1207 b 5 46 47 Uma b 2.54 1,089 2.09 0.061 47 Uma c 0.79 2,594 3.79 0 51 Pegb 0.468 4.23077 0.052 0 55 Cnc b 0.784 14.67 0.115 0.0197 55 Cnc c 0.217 43.93 0.24 0.44 55 Cnc d 3.92 4,517.4 5.257 0.327 55 Cnc e 0.045 2.81 0.038 0.174 70 Vir b 7.44 116.689 0.48 0.4 AB Pic b 13.5 275 BD-10 3166 b 0.48 3.488 0.046 0.07 8 Eridani b 0.86 2,502.1 3.3 0.608 y Cephei b 1.59 902.26 2.03 0.2 GJ 3021 b 3.32 133.82 0.49 0.505 GJ 436 b 0.067 2.644963 0.0278 0.207 Gl 581 b 0.056 5.366 0.041 0 G186b 4.01 15.766 0.11 0.046 Gliese 876 b 1.935 60.94 0.20783 0.0249 Gliese 876 c 0.56 30.1 0.13 0.27 Gliese 876 d 0.023 1.93776 0.0208067 0 GQ Lup b 21.5 103 HD 101930 b 0.3 70.46 0.302 0.11 HD 102117 b 0.14 20.67 0.149 0.06 HD 102195 b 0.488 4.11434 0.049 0.06 HD 104985 b 6.3 198.2 0.78 0.03 1 70 The first 200 extrasolar planets Name Mass Period Semimajor axis Eccentricity (Mj) (years) (AU) (e) HD 106252 -

![Arxiv:1604.04544V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 20 Jul 2017 Ihn00 U Lo Aybnr Trsystems Mul- Star Host Star to Known the Binary Are Which Many Discovered Orbit Been Also, Have E, AU](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6153/arxiv-1604-04544v2-astro-ph-ep-20-jul-2017-ihn00-u-lo-aybnr-trsystems-mul-star-host-star-to-known-the-binary-are-which-many-discovered-orbit-been-also-have-e-au-7946153.webp)

Arxiv:1604.04544V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 20 Jul 2017 Ihn00 U Lo Aybnr Trsystems Mul- Star Host Star to Known the Binary Are Which Many Discovered Orbit Been Also, Have E, AU

Dynamics of a Probable Earth-mass Planet in GJ 832 System S. Satyal1∗, J. Griffith1, Z. E. Musielak1,2 1The Department of Physics, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76019. 2Kiepenheuer-Institut f¨ur Sonnenphysik, Sch¨oneckstr. 6, 79104 Freiburg, Germany. ABSTRACT Stability of planetary orbits around the GJ 832 star system, which contains inner (GJ 832c) and outer (GJ 832b) planets, is investigated numerically and a detailed phase-space analysis is performed. A special emphasis is given to the existence of stable orbits for a planet less than 15M⊕ which is injected between the inner and outer planets. Thus, numerical simulations are performed for three and four bodies in elliptical orbits (or circular for special cases) by using a large number of initial conditions that cover the selected phase-spaces of the planet’s orbital parameters. The results presented in the phase-space maps for GJ 832c indicate the least deviation of eccentricity from its nominal value, which is then used to determine its inclination regime relative to the star-outer planet plane. Also, the injected planet displays stable orbital configurations for at least one billion years. Then, the radial velocity curves based on the signature from the Keplerian motion are generated for the injected planets with masses 1M⊕ to 15M⊕ in order to estimate their semimajor axes and mass-limit. The synthetic RV signal suggests that an additional planet of mass ≤ 15M⊕ with dynamically stable configuration may be residing between 0.25 - 2.0 AU from the star. We have provided an estimated number of RV observations for the additional planet that is required for further observational verification. -

V. Semimajor Axis Calculation 25

Theses - Daytona Beach Dissertations and Theses Spring 2006 Magnetic Coupling between a “Hot Jupiter” Extrasolar Planet and Its Pre-Main-Sequence Central Star Brooke E. Alarcon Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University - Daytona Beach Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/db-theses Part of the Atmospheric Sciences Commons, and the Physics Commons Scholarly Commons Citation Alarcon, Brooke E., "Magnetic Coupling between a “Hot Jupiter” Extrasolar Planet and Its Pre-Main- Sequence Central Star" (2006). Theses - Daytona Beach. 23. https://commons.erau.edu/db-theses/23 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University – Daytona Beach at ERAU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in the Theses - Daytona Beach collection by an authorized administrator of ERAU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAGNETIC COUPLING BETWEEN A "HOT JUPITER" EXTRASOLAR PLANET AND ITS PRE-MAIN-SEQUENCE CENTRAL STAR By Brooke E. Alarcon A thesis Submitted to the Physical Science Department in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Space Science Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Daytona Beach, Florida Spring 2006 UMI Number: EP32031 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.