Scent-Marking by Male Mammals: Cheat-Proof Signals to Competitors and Mates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Antilope Cervicapra) in INDIA

FAECAL CORTISOL METABOLITES AS AN INDICATOR OF STRESS IN CAPTIVE SPOTTED DEER (Axis axis) AND BLACKBUCK (Antilope cervicapra) IN INDIA. BY NIKHIL SOPAN BANGAR (B.V.Sc. & A.H.) MAHARASHTRA ANIMAL AND FISHERY SCIENCES UNIVERSITY, INDIA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN WILDLIFE HEALTH AND MANAGEMENT (WHM) DEPARTMENT OF CLINICAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF VETERINARY MEDICINE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2019 DECLARATION ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my beloved mother, Mrs Suman Sopan Bangar and my father Mr Sopan Bhayappa Bangar for always being supportive and encouraging me to be who I am today. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere gratitude to Dr Muchane Muchai for providing unswerving and continuous feedback throughout the period of my work in this project; Dr Andrew G. Thaiyah both for his support and guidance during the course of thesis; Professor Dhananjay Govind Dighe for valuable guidance while conducting my field work along with laboratory work in India. I am also grateful to Profes- sor Shailesh Ingole and Dr Javed Khan for guiding me throughout my laboratory work. It is with great thanks to Rajiv Gandhi Zoological Park and wildlife research centre management team; Director Dr Rajkumar Jadhav, Deputy Director Dr Navnath Nigot, Head animal keeper Mr Shyamrao Khude along with animal keepers Mr Navnath Memane and Mr Sandip Raykar: Thank you for your untiring inspiration to contribute to my field work. I was enthused every single day working with each of you and learned more than I could ever hope to in such a short time. I hope this work will help contribute to management and development of the zoo. -

The Saola Or Spindlehorn Bovid Pseudoryx Nghetinhensis in Laos

ORYX VOL 29 NO 2 APRIL 1995 The saola or spindlehorn bovid Pseudoryx nghetinhensis in Laos George B. Schaller and Alan Rabinowitz In 1992 the discovery of a new bovid, Pseudoryx nghetinhensis, in Vietnam led to speculation that the species also occurred in adjacent parts of Laos. This paper describes a survey in January 1994, which confirmed the presence of P. ngethinhensis in Laos, although in low densities and with a patchy distribution. The paper also presents new information that helps clarify the phylogenetic position of the species. The low numbers and restricted range ofP. ngethinhensis mean that it must be regarded as Endangered. While some admirable moves have been made to protect the new bovid and its habitat, more needs to be done and the authors recommend further conservation action. Introduction area). Dung et al. (1994) refer to Pseudoryx as the Vu Quang ox, but, given the total range of In May 1992 Do Tuoc and John MacKinnon the animal and its evolutionary affinities (see found three sets of horns of a previously un- below), we prefer to call it by the descriptive described species of bovid in the Vu Quang local name 'saola'. Nature Reserve of west-central Vietnam The village of Nakadok, where saola horns (Stone, 1992). The discovery at the end of the were found, lies at the end of the Nakai-Nam twentieth century of a large new mammal in a Theun National Biodiversity Conservation region that had been visited repeatedly by sci- Area (NNTNBCA), which at 3500 sq km is the entific and other expeditions (Delacour and largest of 17 protected areas established by Jabouille, 1931; Legendre, 1936) aroused in- Laos in October 1993. -

Volatile Cues Influence Host-Choice in Arthropod Pests

animals Review Volatile Cues Influence Host-Choice in Arthropod Pests Jacqueline Poldy Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Health & Biosecurity, Black Mountain Laboratory, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; [email protected]; Tel.: +61-2-6218-3599 Received: 1 October 2020; Accepted: 22 October 2020; Published: 28 October 2020 Simple Summary: Many significant human and animal diseases are spread by blood feeding insects and other arthropod vectors. Arthropod pests and disease vectors rely heavily on chemical cues to identify and locate important resources such as their preferred animal hosts. Although there are abundant studies on the means by which biting insects—especially mosquitoes—are attracted to humans, this focus overlooks the veterinary and medical importance of other host–pest relationships and the chemical signals that underpin them. This review documents the published data on airborne (volatile) chemicals emitted from non-human animals, highlighting the subset of these emissions that play a role in guiding host choice by arthropod pests. The paper exposes some of the complexities associated with existing methods for collecting relevant chemical features from animal subjects, cautions against extrapolating the ecological significance of volatile emissions, and highlights opportunities to explore research gaps. Although the literature is less comprehensive than human studies, understanding the chemical drivers behind host selection creates opportunities to interrupt pest attack and disease transmission, enabling more efficient pest management. Abstract: Many arthropod pests of humans and other animals select their preferred hosts by recognising volatile odour compounds contained in the hosts’ ‘volatilome’. Although there is prolific literature on chemical emissions from humans, published data on volatiles and vector attraction in other species are more sporadic. -

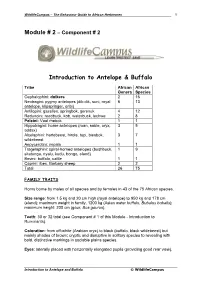

Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo

WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 1 Module # 2 – Component # 2 Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo Tribe African African Genera Species Cephalophini: duikers 2 16 Neotragini: pygmy antelopes (dik-dik, suni, royal 6 13 antelope, klipspringer, oribi) Antilopini: gazelles, springbok, gerenuk 4 12 Reduncini: reedbuck, kob, waterbuck, lechwe 2 8 Peleini: Vaal rhebok 1 1 Hippotragini: horse antelopes (roan, sable, oryx, 3 5 addax) Alcelaphini: hartebeest, hirola, topi, biesbok, 3 7 wildebeest Aepycerotini: impala 1 1 Tragelaphini: spiral-horned antelopes (bushbuck, 1 9 sitatunga, nyalu, kudu, bongo, eland) Bovini: buffalo, cattle 1 1 Caprini: ibex, Barbary sheep 2 2 Total 26 75 FAMILY TRAITS Horns borne by males of all species and by females in 43 of the 75 African species. Size range: from 1.5 kg and 20 cm high (royal antelope) to 950 kg and 178 cm (eland); maximum weight in family, 1200 kg (Asian water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis); maximum height: 200 cm (gaur, Bos gaurus). Teeth: 30 or 32 total (see Component # 1 of this Module - Introduction to Ruminants). Coloration: from off-white (Arabian oryx) to black (buffalo, black wildebeest) but mainly shades of brown; cryptic and disruptive in solitary species to revealing with bold, distinctive markings in sociable plains species. Eyes: laterally placed with horizontally elongated pupils (providing good rear view). Introduction to Antelope and Buffalo © WildlifeCampus WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 2 Scent glands: developed (at least in males) in most species, diffuse or absent in a few (kob, waterbuck, bovines). Mammae: 1 or 2 pairs. Horns. True horns consist of an outer sheath composed mainly of keratin over a bony core of the same shape which grows from the frontal bones. -

GUIDES NEWSLETTER JULY 2019 Written by Isaiah Banda

GUIDES NEWSLETTER JULY 2019 Written By Isaiah Banda The mercury dropped to 3.1 degrees Celsius in the beginning of the month until mid-month here at Safari Plains. Different days of the month it was only at 3.6, but different parts of the reserve experience slight temperature variations, as down in the western side of the lodge was the coldest I’ve felt in a couple of years, and I was in different areas on the reserve during the month, when it didn’t feel as bad. I’m confident it was only just above freezing in some of the depressions this month. I was in a sighting with the Madjuma pride but was particularly loathed to take off my gloves to work the camera, as I knew the kind of pain they would be in within seconds. Not cold… pain! Luckily, I had a company of Riette Smit, she did not hesitate to take her camera out. WWW.SAFARIPLAINS.CO.ZA Invariably in the mornings, the first hour of the drive is quiet. Predators aren’t moving around quite as much, probably conserving energy. It’s usually only when the temperature starts to rise that the action starts, and suddenly the tracking efforts start finding success, and the number of sightings starts to spike. The bush has essentially followed that pattern for the past month; we leave the lodge before sunrise bundled up in at least four layers, numb our faces for an hour or so until we start speaking incoherently, and then just as it’s almost time for a warm cup of coffee, outcomes the wildlife! Curiosity Killed the…. -

The Social and Spatial Organisation of the Beira Antelope (): a Relic from the Past? Nina Giotto, Jean-François Gérard

The social and spatial organisation of the beira antelope (): a relic from the past? Nina Giotto, Jean-François Gérard To cite this version: Nina Giotto, Jean-François Gérard. The social and spatial organisation of the beira antelope (): a relic from the past?. European Journal of Wildlife Research, Springer Verlag, 2009, 56 (4), pp.481-491. 10.1007/s10344-009-0326-8. hal-00535255 HAL Id: hal-00535255 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00535255 Submitted on 11 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Eur J Wildl Res (2010) 56:481–491 DOI 10.1007/s10344-009-0326-8 ORIGINAL PAPER The social and spatial organisation of the beira antelope (Dorcatragus megalotis): a relic from the past? Nina Giotto & Jean-François Gerard Received: 16 March 2009 /Revised: 1 September 2009 /Accepted: 17 September 2009 /Published online: 29 October 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract We studied the social and spatial organisation of Keywords Dwarf antelope . Group dynamics . Grouping the beira (Dorcatragus megalotis) in arid low mountains in pattern . Phylogeny. Territory the South of the Republic of Djibouti. Beira was found to live in socio-spatial units whose ranges were almost non- overlapping, with a surface area of about 0.7 km2. -

MAMMALIAN EXOCRINE SECRETIONS XV. CONSTITUENTS of SECRETION of VENTRAL GLAND of MALE DWARF HAMSTER, Phodopus Sungorus Sungorus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository MAMMALIAN EXOCRINE SECRETIONS XV. CONSTITUENTS OF SECRETION OF VENTRAL GLAND OF MALE DWARF HAMSTER, Phodopus sungorus sungorus B. V. BURGER, D. SMIT, H. S. C. SPIES Laboratory for Ecological Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, 7600, South Africa. C. SCHMIDT, U. SCHMIDT Zoological Institute, University of Bonn, Poppelsdorfer Schloss, D-53115 Bonn, Germany. A. Y. TELITSINA, Institute of Animal Evolutionary Morphology and Ecology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninsky 33, Moscow, 117071, Russia. G. R. GRIERSON Rothmans International, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa. Abstract In a study aimed at the chemical characterization of constituents of the ventral gland secretion of the male dwarf hamster, Phodopus sungorus sun- gorus, 48 compounds, including saturated alcohols, saturated and unsaturated ketones, saturated and unsaturated straight-chain carboxylic acids, iso- and an- teisocarboxylic acids, 3-phenylpropanoic acid, hydroxyesters, 2-piperidone, and some steroids were identified in the secretion. The position of the double bonds in γ -icosadienyl-γ -butyrolactone and γ - henicosadienyl-γ -butyrolactone, and the position of methylbranching in seven C16 –C21 saturated ketones could not be established. Several constituents with typically steroidal mass spectra also remained unidentified. The female dwarf hamster’s ventral gland either does not produce secretion -

Annales Zoologici Fennici 35: 149-162

Ann. Zool. Fennici 35: 149–162 ISSN 0003-455X Helsinki 11 December 1998 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 1998 Ammotragus lervia: a review on systematics, biology, ecology and distribution Jorge Cassinello Cassinello, J., Estación Experimental de Zonas Aridas, CSIC, C/General Segura 1, ESP-04001 Almería, Spain; and Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, C/José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, ESP-28006 Madrid, Spain 1) Received 28 April 1998, accepted 9 August 1998 A revision on the current knowledge of the genus Ammotragus is provided. There is only one species, A. lervia, which is considered an ancestor of both Ovis and Capra. Six sub- species originally distributed in the North of Africa, but also introduced elsewhere, have been described. Particularly the study of the introduced wild ranging American populations, and recent research carried out on a captive population in Spain have expanded our knowl- edge on the species’ social behaviour, reproduction, female fitness components, behav- ioural ecology, feeding habits and ecology. Native and introduced populations of arruis are facing different problems; the former ones are generally threatened by human pression, and the latter ones pose a serious risk to native ungulates and plants. 1. Short foreword zoos, or on American wild populations (e.g., Haas 1959, Simpson 1980, my own work). Herewith a Ammotragus lervia is an African ungulate retain- review on the literature available and suggestion ing some primitive and unique characteristics for future research are provided. which makes it particularly interesting for re- Common names for the species are: aoudad, search. It is also considered as a vulnerable spe- audad, udad, uaddan, ouaddan, aroui, arui, arrui, cies by IUCN (1996). -

Buck Odor Production in the Cornual Gland of the Male Goat, Capra Hircus– Validation with Histoarchitecture, Volatile and Proteomic Analysis

Indian Journal of Biochemistry & Biophysics Vol. 55, June 2018, pp. 183-190 Buck odor production in the cornual gland of the male goat, Capra hircus– Validation with histoarchitecture, volatile and proteomic analysis Devaraj Sankarganesh1,#, Rajamanickam Ramachandran1,2, Radhakrishnan Ashok1, Veluchamy Ramesh Saravanakumar3, Raman Sukirtha1, Govindaraju Archunan4* & Shanmugam Achiraman1,4* 1Department of Environmental Biotechnology, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli-620 024, Tamil Nadu, India 2Department of Microbial Biotechnology, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore-641 046, Tamil Nadu, India 3Department of Livestock Production and Management, Veterinary College and Research Institute, Namakkal-637 002, Tamil Nadu, India 4Center for Pheromone Technology, Department of Animal Science, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli- 620 024, Tamil Nadu, India Received 28 January 2018; revised 14 May 2018 In many animals, glandular secretions or pheromones that possess biological moieties contain messages encoded by the intrinsic smell. In male goats, the cornual gland (a sebaceous gland), may synthesize and excrete relevant chemical components that are responsible for the ‘buck effect’. To test this, cornual glands from freshly-slaughtered male goats (N=6) were subjected to histoarchitecture analysis, to infer about the structural alignment, to the GC–MS analysis for volatile compounds and to SDS–PAGE for protein profiling followed by MALDI-TOF to characterize specific protein bands. The gland possesses sebum, vacuoles and hair follicles inferring its capability to synthesize and extrude the scent. We found 14 volatiles in GC–MS analysis, in which 1-octadecanol might be a putative pheromone of buck odor. We identified seven different proteins in SDS-PAGE. Two proteins, 28 and 33 kDa, were highly matched with DNA mismatch repair protein and Abietadiene synthase, respectively, as inferred from MALDI-TOF. -

Tempo and Mode of Domestication During The

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2014 Tempo and Mode of Domestication During the Neolithic Revolution: Evidence from Dental Mesowear and Microwear of Sheep Melissa Zolnierz University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Paleobiology Commons Recommended Citation Zolnierz, Melissa, "Tempo and Mode of Domestication During the Neolithic Revolution: Evidence from Dental Mesowear and Microwear of Sheep" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 2181. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Tempo and Mode of Domestication During the Neolithic Revolution: Evidence from Dental Mesowear and Microwear of Sheep Tempo and Mode of Domestication During the Neolithic Revolution: Evidence from Dental Mesowear and Microwear of Sheep A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Melissa Zolnierz Loyola University Chicago Bachelor of Science in Anthropology, 2003 University of Indianapolis Master of Science in Human Biology, 2008 August 2014 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _________________________ Dr. Peter Ungar Dissertation Director _________________________ _________________________ Dr. Jesse Casana Dr. Jerome Rose Committee Member Committee Member Abstract The Neolithic Revolution marked a dramatic change in human subsistence practices. In order to explain this change, we must understand the motive forces behind it. -

Factors Affecting Preorbital Gland Opening in Red Deer Calves1

Habituating to handling: Factors affecting preorbital gland opening in red deer calves1 F. Ceacero,*†2 T. Landete-Castillejos,‡§# J. Bartošová,* A. J. García,‡§# L. Bartoš,* M. Komárková,* and L. Gallego‡ *Department of Ethology, Institute of Animal Science, Praha 10-Uhříněves, Czech Republic; †Department of Animal Science and Food Processing, Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Czech University of Life Sciences. Prague 6-Suchdol, Czech Republic; ‡Departamento de Ciencia y Tecnología Agroforestal y Genética, ETSIA, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. Albacete, Spain; §Sección de Recursos Cinegéticos, IDR, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. Albacete, Spain; and #Animal Science Techniques Applied to Wildlife Management Research Group, IREC Sec. Albacete. Albacete, Spain ABSTRACT: The preorbital gland plays not only an blood sampling, and rump touching to assess body con- olfactory role in cervids but also a visual one. Opening dition) when calves were 1, 3, and 5 mo old. Binary this gland is an easy way for the calf to communicate logistic regression showed that gland opening was asso- with the mother, indicating hunger/satiety, stress, pain, ciated with habituation to handling, since at 1 and 3 mo fear, or excitement. This information can be also useful the probability of opening the gland decreased with the for farm operators to assess how fast the calves habitu- number of handlings that a calf experienced before (P = ate to handling routines and to detect those calves that 0.008 and P = 0.028, respectively). However, there were do not habituate and may suffer chronic stress in the no further changes in preorbital gland opening rate in future. Thirty-one calves were subjected to 2 consecu- the 5-mo-old calves (P = 0.182). -

IJEB 56(11) 781-794.Pdf

Indian Journal of Experimental Biology Vol. 56, November 2018, pp. 781-794 Inter-relationship of behaviour, faecal testosterone levels and glandular volatiles in determination of dominance in male Blackbuck Thangavel Rajagopal1,2, Ponnirul Ponmanickam3, Arunachalam Chinnathambi4, Parasuraman Padmanabhan5, Balazs Gulyas5 & Govindaraju Archunan1* 1Pheromone Technology Lab, Department of Animal Science, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli-620 024, Tamil Nadu, India 2Department of Zoology and Microbiology, Thiagarajar College (Autonomous), Madurai-625 009, Tamil Nadu, India 3Department of Zoology, Ayya Nadar Janaki Ammal College (Autonomous), Sivakasi 626 124, Tamil Nadu, India 4Department of Botany and Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia-11451 5Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore-637553 Received 28 March 2017; revised 25 November 2017 The social hierarchy of blackbuck plays a crucial role in mate selection and establishment of hierarchy in order to maintain successful reproduction. The factors that influence dominancy have not been yet investigated in the Indian male blackbuck. Here, we investigated the interrelationships between behaviours (aggressive and scent marking), chemical profiles of preorbital gland secretion and faecal testosterone levels in male blackbuck with special reference to dominance hierarchy. The frequency of aggressive behaviour, preorbital gland scent marking behaviour and faecal testosterone level were significantly higher (P <0.001) in the dominant males than the other males. Among the 43 major volatile compounds identified in the pre-orbital gland posting of dominant and subordinate male Blackbucks, four compounds viz., 2-methyl propanoic acid (I), 2-methyl-4-heptanone (II), 2,7-dimethyl-1-octanol (III) and 1,15-pentadecanediol (IV) were present only in the preorbital gland post of the dominant male during the hierarchy period.