Identifying Whitetail/Mule Deer Hybrids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deer, Elk, Bear, Moose, Lynx, Bobcat, Waterfowl

Hunt ID: 1501-CA-AL-G-L-MDeerWDeerElkBBearMooseLynxBobcatWaterfowl-M1SR-O1G-N2EGE Great Economy Deer and Moose Hunts south of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada American Hunters trekking to Canada for low cost moose, along with big Mule Deer and Whitetail and been pleasantly surprised by the weather and temperatures that they were greeted by when they hunted British Columbia, located in Canada, north of Washington State. Canada should be and is cold but there are exceptions, if you know where to go. In BC if you stay on the western Side of the Rocky Mountains the weather is quite mild because it is warmed by the Pacific Ocean. If you hunt east of the Rocky Mountains, what I call the Canadian Interior it can be as much as 50 degrees colder depending on the time of the year. The area has now preference point requirements, the Outfitter has his allotted vouchers so you can get a reasonably priced license and, in most cases, less than you can get for the same animal in the US as a non-resident. You don’t even buy the voucher from the Outfitter it is part of his hunt cost because without it you could not get a license anyway. Travel is easy and the residents are friendly. Like anywhere outside the US you will need a easy to acquire Passport if you don’t have one, just don’t wait until the last minute to get one for $10 from your local Post office by where you live. The one thing in Canada is if you have a felony on your record Canada will not allow you into their safe Country. -

Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist

STATE OF NEVADA Steve Sisolak, Governor DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Tony Wasley, Director GAME DIVISION Brian F. Wakeling, Chief Mike Cox, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goat Staff Specialist Pat Jackson, Predator Management Staff Specialist Cody McKee, Elk Staff Biologist Cody Schroeder, Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist Western Region Southern Region Eastern Region Regional Supervisors Mike Scott Steve Kimble Tom Donham Big Game Biologists Chris Hampson Joe Bennett Travis Allen Carl Lackey Pat Cummings Clint Garrett Kyle Neill Cooper Munson Sarah Hale Ed Partee Kari Huebner Jason Salisbury Matt Jeffress Kody Menghini Tyler Nall Scott Roberts This publication will be made available in an alternative format upon request. Nevada Department of Wildlife receives funding through the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration. Federal Laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex, or disability. If you believe you’ve been discriminated against in any NDOW program, activity, or facility, please write to the following: Diversity Program Manager or Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Nevada Department of Wildlife 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Mailstop: 7072-43 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Suite 120 Arlington, VA 22203 Reno, Nevada 8911-2237 Individuals with hearing impairments may contact the Department via telecommunications device at our Headquarters at 775-688-1500 via a text telephone (TTY) telecommunications device by first calling the State of Nevada Relay Operator at 1-800-326-6868. NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE 2018-2019 BIG GAME STATUS This program is supported by Federal financial assistance titled “Statewide Game Management” submitted to the U.S. -

Habitat Guidelines for Mule Deer: California Woodland Chaparral Ecoregion

THE AUTHORS : MARY L. SOMMER CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME WILDLIFE BRANCH 1812 NINTH STREET SACRAMENTO, CA 95814 REBECCA L. BARBOZA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME SOUTH COAST REGION 4665 LAMPSON AVENUE, SUITE C LOS ALAMITOS, CA 90720 RANDY A. BOTTA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME SOUTH COAST REGION 4949 VIEWRIDGE AVENUE SAN DIEGO, CA 92123 ERIC B. KLEINFELTER CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME CENTRAL REGION 1234 EAST SHAW AVENUE FRESNO, CA 93710 MARTHA E. SCHAUSS CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME CENTRAL REGION 1234 EAST SHAW AVENUE FRESNO, CA 93710 J. ROCKY THOMPSON CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME CENTRAL REGION P.O. BOX 2330 LAKE ISABELLA, CA 93240 Cover photo by: California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) Suggested Citation: Sommer, M. L., R. L. Barboza, R. A. Botta, E. B. Kleinfelter, M. E. Schauss and J. R. Thompson. 2007. Habitat Guidelines for Mule Deer: California Woodland Chaparral Ecoregion. Mule Deer Working Group, Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 THE CALIFORNIA WOODLAND CHAPARRAL ECOREGION 4 Description 4 Ecoregion-specific Deer Ecology 4 MAJOR IMPACTS TO MULE DEER HABITAT 6 IN THE CALIFORNIA WOODLAND CHAPARRA L CONTRIBUTING FACTORS AND SPECIFIC 7 HABITAT GUIDELINES Long-term Fire Suppression 7 Human Encroachment 13 Wild and Domestic Herbivores 18 Water Availability and Hydrological Changes 26 Non-native Invasive Species 30 SUMMARY 37 LITERATURE CITED 38 APPENDICIES 46 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ule and black-tailed deer (collectively called Forest is severe winterkill. Winterkill is not a mule deer, Odocoileus hemionus ) are icons of problem in the Southwest Deserts, but heavy grazing the American West. -

(Antilope Cervicapra) in INDIA

FAECAL CORTISOL METABOLITES AS AN INDICATOR OF STRESS IN CAPTIVE SPOTTED DEER (Axis axis) AND BLACKBUCK (Antilope cervicapra) IN INDIA. BY NIKHIL SOPAN BANGAR (B.V.Sc. & A.H.) MAHARASHTRA ANIMAL AND FISHERY SCIENCES UNIVERSITY, INDIA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN WILDLIFE HEALTH AND MANAGEMENT (WHM) DEPARTMENT OF CLINICAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF VETERINARY MEDICINE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2019 DECLARATION ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my beloved mother, Mrs Suman Sopan Bangar and my father Mr Sopan Bhayappa Bangar for always being supportive and encouraging me to be who I am today. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere gratitude to Dr Muchane Muchai for providing unswerving and continuous feedback throughout the period of my work in this project; Dr Andrew G. Thaiyah both for his support and guidance during the course of thesis; Professor Dhananjay Govind Dighe for valuable guidance while conducting my field work along with laboratory work in India. I am also grateful to Profes- sor Shailesh Ingole and Dr Javed Khan for guiding me throughout my laboratory work. It is with great thanks to Rajiv Gandhi Zoological Park and wildlife research centre management team; Director Dr Rajkumar Jadhav, Deputy Director Dr Navnath Nigot, Head animal keeper Mr Shyamrao Khude along with animal keepers Mr Navnath Memane and Mr Sandip Raykar: Thank you for your untiring inspiration to contribute to my field work. I was enthused every single day working with each of you and learned more than I could ever hope to in such a short time. I hope this work will help contribute to management and development of the zoo. -

Utah Pronghorn Statewide Management Plan

UTAH PRONGHORN STATEWIDE MANAGEMENT PLAN UTAH DIVISION OF WILDLIFE RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES UTAH DIVISION OF WILDLIFE RESOURCES STATEWIDE MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR PRONGHORN I. PURPOSE OF THE PLAN A. General This document is the statewide management plan for pronghorn in Utah. This plan will provide overall direction and guidance to Utah’s pronghorn management activities. Included in the plan is an assessment of current life history and management information, identification of issues and concerns relating to pronghorn management in the state, and the establishment of goals, objectives and strategies for future management. The statewide plan will provide direction for establishment of individual pronghorn unit management plans throughout the state. B. Dates Covered This pronghorn plan will be in effect upon approval of the Wildlife Board (expected date of approval November 30, 2017) and subject to review within 10 years. II. SPECIES ASSESSMENT A. Natural History The pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) is the sole member of the family Antilocapridae and is native only to North America. Fossil records indicate that the present-day form may go back at least a million years (Kimball and Johnson 1978). The name pronghorn is descriptive of the adult male’s large, black-colored horns with anterior prongs that are shed each year in late fall or early winter. Females also have horns, but they are shorter and seldom pronged. Mature pronghorn bucks weigh 45–60 kilograms (100–130 pounds) and adult does weigh 35–45 kilograms (75–100 pounds). Pronghorn are North America’s fastest land mammal and can attain speeds of approximately 72 kilometers (45 miles) per hour (O’Gara 2004a). -

AWA IR C-AK Secure.Pdf

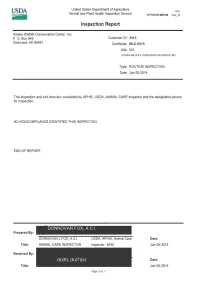

United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3415 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 25-JUN-14 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 3415 96-C-0015 001 ALASKA WILDLIFE 25-JUN-14 CONSERVATION CENTER INC. Count Species 000002 Canadian lynx 000004 Reindeer 000009 Muskox 000004 Moose 000002 North American black bear 000003 Brown bear 000001 North American porcupine 000130 American bison 000001 Red fox 000021 Elk 000177 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 7106 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 15-SEP-14 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 7106 96-C-0024 001 S.A.A.M.S 15-SEP-14 Count Species 000008 Stellers northern sealion 000006 Harbor seal 000003 Sea otter 000017 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 7106 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 24-JUN-15 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 7106 96-C-0024 001 S.A.A.M.S 24-JUN-15 Count Species 000008 Stellers northern sealion 000006 Harbor seal 000014 Total DBARKSDALE United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service 2016082567946548 Insp_id Inspection Report S.A.A.M.S Customer ID: 7106 P. O. Box 1329 Certificate: 96-C-0024 Seward, AK 99664 Site: 001 S.A.A.M.S Type: ROUTINE INSPECTION Date: 26-SEP-2016 No non-compliant items identified during this inspection. This inspection and exit briefing was conducted with facility representatives. -

The Saola Or Spindlehorn Bovid Pseudoryx Nghetinhensis in Laos

ORYX VOL 29 NO 2 APRIL 1995 The saola or spindlehorn bovid Pseudoryx nghetinhensis in Laos George B. Schaller and Alan Rabinowitz In 1992 the discovery of a new bovid, Pseudoryx nghetinhensis, in Vietnam led to speculation that the species also occurred in adjacent parts of Laos. This paper describes a survey in January 1994, which confirmed the presence of P. ngethinhensis in Laos, although in low densities and with a patchy distribution. The paper also presents new information that helps clarify the phylogenetic position of the species. The low numbers and restricted range ofP. ngethinhensis mean that it must be regarded as Endangered. While some admirable moves have been made to protect the new bovid and its habitat, more needs to be done and the authors recommend further conservation action. Introduction area). Dung et al. (1994) refer to Pseudoryx as the Vu Quang ox, but, given the total range of In May 1992 Do Tuoc and John MacKinnon the animal and its evolutionary affinities (see found three sets of horns of a previously un- below), we prefer to call it by the descriptive described species of bovid in the Vu Quang local name 'saola'. Nature Reserve of west-central Vietnam The village of Nakadok, where saola horns (Stone, 1992). The discovery at the end of the were found, lies at the end of the Nakai-Nam twentieth century of a large new mammal in a Theun National Biodiversity Conservation region that had been visited repeatedly by sci- Area (NNTNBCA), which at 3500 sq km is the entific and other expeditions (Delacour and largest of 17 protected areas established by Jabouille, 1931; Legendre, 1936) aroused in- Laos in October 1993. -

Volatile Cues Influence Host-Choice in Arthropod Pests

animals Review Volatile Cues Influence Host-Choice in Arthropod Pests Jacqueline Poldy Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Health & Biosecurity, Black Mountain Laboratory, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; [email protected]; Tel.: +61-2-6218-3599 Received: 1 October 2020; Accepted: 22 October 2020; Published: 28 October 2020 Simple Summary: Many significant human and animal diseases are spread by blood feeding insects and other arthropod vectors. Arthropod pests and disease vectors rely heavily on chemical cues to identify and locate important resources such as their preferred animal hosts. Although there are abundant studies on the means by which biting insects—especially mosquitoes—are attracted to humans, this focus overlooks the veterinary and medical importance of other host–pest relationships and the chemical signals that underpin them. This review documents the published data on airborne (volatile) chemicals emitted from non-human animals, highlighting the subset of these emissions that play a role in guiding host choice by arthropod pests. The paper exposes some of the complexities associated with existing methods for collecting relevant chemical features from animal subjects, cautions against extrapolating the ecological significance of volatile emissions, and highlights opportunities to explore research gaps. Although the literature is less comprehensive than human studies, understanding the chemical drivers behind host selection creates opportunities to interrupt pest attack and disease transmission, enabling more efficient pest management. Abstract: Many arthropod pests of humans and other animals select their preferred hosts by recognising volatile odour compounds contained in the hosts’ ‘volatilome’. Although there is prolific literature on chemical emissions from humans, published data on volatiles and vector attraction in other species are more sporadic. -

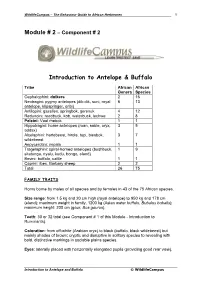

Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo

WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 1 Module # 2 – Component # 2 Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo Tribe African African Genera Species Cephalophini: duikers 2 16 Neotragini: pygmy antelopes (dik-dik, suni, royal 6 13 antelope, klipspringer, oribi) Antilopini: gazelles, springbok, gerenuk 4 12 Reduncini: reedbuck, kob, waterbuck, lechwe 2 8 Peleini: Vaal rhebok 1 1 Hippotragini: horse antelopes (roan, sable, oryx, 3 5 addax) Alcelaphini: hartebeest, hirola, topi, biesbok, 3 7 wildebeest Aepycerotini: impala 1 1 Tragelaphini: spiral-horned antelopes (bushbuck, 1 9 sitatunga, nyalu, kudu, bongo, eland) Bovini: buffalo, cattle 1 1 Caprini: ibex, Barbary sheep 2 2 Total 26 75 FAMILY TRAITS Horns borne by males of all species and by females in 43 of the 75 African species. Size range: from 1.5 kg and 20 cm high (royal antelope) to 950 kg and 178 cm (eland); maximum weight in family, 1200 kg (Asian water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis); maximum height: 200 cm (gaur, Bos gaurus). Teeth: 30 or 32 total (see Component # 1 of this Module - Introduction to Ruminants). Coloration: from off-white (Arabian oryx) to black (buffalo, black wildebeest) but mainly shades of brown; cryptic and disruptive in solitary species to revealing with bold, distinctive markings in sociable plains species. Eyes: laterally placed with horizontally elongated pupils (providing good rear view). Introduction to Antelope and Buffalo © WildlifeCampus WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 2 Scent glands: developed (at least in males) in most species, diffuse or absent in a few (kob, waterbuck, bovines). Mammae: 1 or 2 pairs. Horns. True horns consist of an outer sheath composed mainly of keratin over a bony core of the same shape which grows from the frontal bones. -

Brochure Highlight Those Impressive Russia

2019 44 years and counting The products and services listed Join us on Facebook, follow us on Instagram or visit our web site to become one Table of Contents in advertisements are offered and of our growing number of friends who receive regular email updates on conditions Alaska . 4 provided solely by the advertiser. and special big game hunt bargains. Australia . 38 www.facebook.com/NealAndBrownleeLLC Neal and Brownlee, L.L.C. offers Austria . 35 Instagram: @NealAndBrownleeLLC no guarantees, warranties or Azerbaijan . 31 recommendations for the services or Benin . 18 products offered. If you have questions Cameroon . 19 related to these services, please contact Canada . 6 the advertiser. Congo . 20 All prices, terms and conditions Continental U .S . 12 are, to the best of our knowledge at the Ethiopia . 20 time of printing, the most recent and Fishing Alaska . 42 accurate. Prices, terms and conditions Fishing British Columbia . 41 are subject to change without notice Fishing New Zealand . 42 due to circumstances beyond our Kyrgyzstan . 31 control. Jeff C. Neal Greg Brownlee Trey Sperring Mexico . 14 Adventure travel and big game 2018 was another fantastic year for our company thanks to the outfitters we epresentr and the Mongolia . 32 hunting contain inherent risks and clients who trusted us. We saw more clients traveling last season than in any season in the past, Mozambique . 21 dangers by their very nature that with outstanding results across the globe. African hunting remained strong, with our primary Namibia . 22 are beyond the control of Neal and areas producing outstanding success across several countries. Asian hunting has continued to be Nepal . -

GUIDES NEWSLETTER JULY 2019 Written by Isaiah Banda

GUIDES NEWSLETTER JULY 2019 Written By Isaiah Banda The mercury dropped to 3.1 degrees Celsius in the beginning of the month until mid-month here at Safari Plains. Different days of the month it was only at 3.6, but different parts of the reserve experience slight temperature variations, as down in the western side of the lodge was the coldest I’ve felt in a couple of years, and I was in different areas on the reserve during the month, when it didn’t feel as bad. I’m confident it was only just above freezing in some of the depressions this month. I was in a sighting with the Madjuma pride but was particularly loathed to take off my gloves to work the camera, as I knew the kind of pain they would be in within seconds. Not cold… pain! Luckily, I had a company of Riette Smit, she did not hesitate to take her camera out. WWW.SAFARIPLAINS.CO.ZA Invariably in the mornings, the first hour of the drive is quiet. Predators aren’t moving around quite as much, probably conserving energy. It’s usually only when the temperature starts to rise that the action starts, and suddenly the tracking efforts start finding success, and the number of sightings starts to spike. The bush has essentially followed that pattern for the past month; we leave the lodge before sunrise bundled up in at least four layers, numb our faces for an hour or so until we start speaking incoherently, and then just as it’s almost time for a warm cup of coffee, outcomes the wildlife! Curiosity Killed the…. -

The Social and Spatial Organisation of the Beira Antelope (): a Relic from the Past? Nina Giotto, Jean-François Gérard

The social and spatial organisation of the beira antelope (): a relic from the past? Nina Giotto, Jean-François Gérard To cite this version: Nina Giotto, Jean-François Gérard. The social and spatial organisation of the beira antelope (): a relic from the past?. European Journal of Wildlife Research, Springer Verlag, 2009, 56 (4), pp.481-491. 10.1007/s10344-009-0326-8. hal-00535255 HAL Id: hal-00535255 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00535255 Submitted on 11 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Eur J Wildl Res (2010) 56:481–491 DOI 10.1007/s10344-009-0326-8 ORIGINAL PAPER The social and spatial organisation of the beira antelope (Dorcatragus megalotis): a relic from the past? Nina Giotto & Jean-François Gerard Received: 16 March 2009 /Revised: 1 September 2009 /Accepted: 17 September 2009 /Published online: 29 October 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract We studied the social and spatial organisation of Keywords Dwarf antelope . Group dynamics . Grouping the beira (Dorcatragus megalotis) in arid low mountains in pattern . Phylogeny. Territory the South of the Republic of Djibouti. Beira was found to live in socio-spatial units whose ranges were almost non- overlapping, with a surface area of about 0.7 km2.