Sexual Selection and Social Rank in Bighorn Rams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horned Animals

Horned Animals In This Issue In this issue of Wild Wonders you will discover the differences between horns and antlers, learn about the different animals in Alaska who have horns, compare and contrast their adaptations, and discover how humans use horns to make useful and decorative items. Horns and antlers are available from local ADF&G offices or the ARLIS library for teachers to borrow. Learn more online at: alaska.gov/go/HVNC Contents Horns or Antlers! What’s the Difference? 2 Traditional Uses of Horns 3 Bison and Muskoxen 4-5 Dall’s Sheep and Mountain Goats 6-7 Test Your Knowledge 8 Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2018 Issue 8 1 Sometimes people use the terms horns and antlers in the wrong manner. They may say “moose horns” when they mean moose antlers! “What’s the difference?” they may ask. Let’s take a closer look and find out how antlers and horns are different from each other. After you read the information below, try to match the animals with the correct description. Horns Antlers • Made out of bone and covered with a • Made out of bone. keratin layer (the same material as our • Grow and fall off every year. fingernails and hair). • Are grown only by male members of the • Are permanent - they do not fall off every Cervid family (hoofed animals such as year like antlers do. deer), except for female caribou who also • Both male and female members in the grow antlers! Bovid family (cloven-hoofed animals such • Usually branched. -

Pronghorn G TAG

ANTELOPE AND ... the American “antelope”! IRAFFE Pronghorn G TAG Why exhibit pronghorns? • Celebrate our local biodiversity by displaying the last surviving species of the Antilocapridae, a mammalian family endemic to North America. • Participate in a recovery program close to home: AZA maintains a priority insurance population of the critically endangered peninsular pronghorn. • Engage guests with these “antelope” from the familiar song “Home on the Range” (even though pronghorns aren’t true “antelope” at all!). • Let visitors get hands-on with the unusual horn sheaths of pronghorns - they are keratinous like horns, but are shed annually like antlers! • Seek partnerships with local running groups: pronghorn are the fastest land animals in North America, able to cover 6 miles in 9 minutes! • TAG Recommendation: Contact the SSP for guidance regarding which pronghorn program is best suited to your facility’s climate. MEASUREMENTS IUCN LEAST Length: 4.5 feet CONCERN Height: 3 feet (CITES I) Stewardship Opportunities at shoulder Peninsular Pronghorn Recovery Project Weight: 65-130 lbs <200 peninsular Contact Melodi Tayles: [email protected] Prairies North America in the wild Care and Husbandry RED SSP (peninsular): 25.26 (51) in 7 AZA institutions (2019) Species coordinator: Melodi Tayles, San Diego Zoo Safari Park [email protected] ; (760) 855-1911 CANDIDATE Program (generic): 34.61 (95) in 21 institutions (2014) Social nature: Herd living. Harem groups with a single male are typical. Bachelor groups may be successful in the absence of females. Mixed species: Pronghorn are frequently exhibited with bison. They have also been housed with camels, deer, cranes, and waterfowl. Housing: Peninsular pronghorn are heat tolerant and do well in windy conditions, but heated shelters recommended where temperatures fall below 40ºF for extended periods. -

Play Behavior and Dominance Relationships of Bighorn Sheep on the National Bison Range

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1986 Play behavior and dominance relationships of bighorn sheep on the National Bison Range Christine C. Hass The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hass, Christine C., "Play behavior and dominance relationships of bighorn sheep on the National Bison Range" (1986). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 7375. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/7375 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 This is an unpublished m a n u s c r i p t in w h i c h c o p y r i g h t s u b s i s t s . Any further r e p r i n t i n g of its c o n t e n t s m ust be a p p r o v e d BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD L ibrary Un i v e r s i t y of McwTANA Date : 1 98ft. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

(Antilope Cervicapra) in INDIA

FAECAL CORTISOL METABOLITES AS AN INDICATOR OF STRESS IN CAPTIVE SPOTTED DEER (Axis axis) AND BLACKBUCK (Antilope cervicapra) IN INDIA. BY NIKHIL SOPAN BANGAR (B.V.Sc. & A.H.) MAHARASHTRA ANIMAL AND FISHERY SCIENCES UNIVERSITY, INDIA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN WILDLIFE HEALTH AND MANAGEMENT (WHM) DEPARTMENT OF CLINICAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF VETERINARY MEDICINE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2019 DECLARATION ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my beloved mother, Mrs Suman Sopan Bangar and my father Mr Sopan Bhayappa Bangar for always being supportive and encouraging me to be who I am today. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere gratitude to Dr Muchane Muchai for providing unswerving and continuous feedback throughout the period of my work in this project; Dr Andrew G. Thaiyah both for his support and guidance during the course of thesis; Professor Dhananjay Govind Dighe for valuable guidance while conducting my field work along with laboratory work in India. I am also grateful to Profes- sor Shailesh Ingole and Dr Javed Khan for guiding me throughout my laboratory work. It is with great thanks to Rajiv Gandhi Zoological Park and wildlife research centre management team; Director Dr Rajkumar Jadhav, Deputy Director Dr Navnath Nigot, Head animal keeper Mr Shyamrao Khude along with animal keepers Mr Navnath Memane and Mr Sandip Raykar: Thank you for your untiring inspiration to contribute to my field work. I was enthused every single day working with each of you and learned more than I could ever hope to in such a short time. I hope this work will help contribute to management and development of the zoo. -

Understanding Spike Buck Harvest Twenty-Six Years of Penned Deer Research at the Kerr Wildlife Management Area

Understanding Spike Buck Harvest Twenty-six Years of Penned Deer Research at the Kerr Wildlife Management Area by Bill Armstrong Table of Contents I. Introduction, Background, and Definitions II. The Studies III. Other Related Facts, Results and Discussions: IV. Applying These Studies to Real World Management Programs V Other management concerns: VI. Kerr Wildlife Management Area Penned Deer Studies, Publications 1977-1999 VII. Appendices A. Examples of gene interactions on phenotype and examples of changing gene frequencies in populations B. —Effects of Genetics and Nutrition on Antler Development and Body Size of White-tailed Deer“. C. —Heritabilities for Antler Characteristics and Body Weight in Yearling White- Tailed Deer“ D. —Antler Characteristics and Body Mass of Spike- and Fork-antlered Yearling White-tailed Deer at Maturity“ E. Updated antler characteristic frequency charts for —Effects of Genetics and Nutrition on Antler Development and Body Size of White-tailed Deer“. F. Updated antler characteristics and body weight by age and yearling status comparison charts for the bulletin,—Effects of Genetics and Nutrition on Antler Development and Body Size of White-tailed Deer“. G. Genetic/Environmental Interaction study œ Antler characteristic and body weight trend charts. Cover: The yellow ear tagged deer is a 3-year old deer that was a spike as a yearling. The larger deer is a 4-year old deer that was a fork-antlered yearling. Understanding Spike Buck Harvest by Bill Armstrong Kerr Wildlife Management Area I. Introduction, Background, and Definitions In the mid 1920s , a game law was passed in Texas which protected spike antlered deer. The belief then was that spike antlered deer were young deer and would eventually grow into big deer. -

Utah Pronghorn Statewide Management Plan

UTAH PRONGHORN STATEWIDE MANAGEMENT PLAN UTAH DIVISION OF WILDLIFE RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES UTAH DIVISION OF WILDLIFE RESOURCES STATEWIDE MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR PRONGHORN I. PURPOSE OF THE PLAN A. General This document is the statewide management plan for pronghorn in Utah. This plan will provide overall direction and guidance to Utah’s pronghorn management activities. Included in the plan is an assessment of current life history and management information, identification of issues and concerns relating to pronghorn management in the state, and the establishment of goals, objectives and strategies for future management. The statewide plan will provide direction for establishment of individual pronghorn unit management plans throughout the state. B. Dates Covered This pronghorn plan will be in effect upon approval of the Wildlife Board (expected date of approval November 30, 2017) and subject to review within 10 years. II. SPECIES ASSESSMENT A. Natural History The pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) is the sole member of the family Antilocapridae and is native only to North America. Fossil records indicate that the present-day form may go back at least a million years (Kimball and Johnson 1978). The name pronghorn is descriptive of the adult male’s large, black-colored horns with anterior prongs that are shed each year in late fall or early winter. Females also have horns, but they are shorter and seldom pronged. Mature pronghorn bucks weigh 45–60 kilograms (100–130 pounds) and adult does weigh 35–45 kilograms (75–100 pounds). Pronghorn are North America’s fastest land mammal and can attain speeds of approximately 72 kilometers (45 miles) per hour (O’Gara 2004a). -

Hooves and Herds Lesson Plan

Hooves and Herds 6-8 grade Themes: Rut (breeding) in ungulates (hoofed mammals) Location: Materials: The lesson can be taught in the classroom or a hybrid of in WDFW PowerPoints: Introduction to Ungulates in Washington, the classroom and on WDFW public lands. We encourage Rut in Washington Ungulates, Ungulate comparison sheet, teachers and parents to take students in the field so they WDFW career profile can look for signs of rut in ungulates (hoofed animals) and experience the ecosystems where ungulates call home. Vocabulary: If your group size is over 30 people, you must apply for a Biological fitness: How successful an individual is at group permit. To do this, please e-mail or call your WDFW reproducing relative to others in the population. regional customer service representative. Bovid: An ungulate with permanent keratin horns. All males have horns and, in many species, females also have horns. Check out other WDFW public lands rules and parking Examples are cows, sheep, and goats. information. Cervid: An ungulate with antlers that fall off and regrow every Remote learning modification: Lesson can be taught over year. Antlers are almost exclusively found on males (exception Zoom or Google Classrooms. is caribou). Examples include deer, elk, and moose. Harem: A group of breeding females associated with one breeding male. Standards: Herd: A large group of animals, especially hoofed mammals, NGSS that live, feed, or migrate. MS-LS1-4 Mammal: Animals that are warm blooded, females have Use argument based on empirical evidence and scientific mammary glands that produce milk for feeding their young, reasoning to support an explanation for how characteristic three bones in the middle ear, fur or hair (in at least one stage animal behaviors and specialized plant structures affect the of their life), and most give live birth. -

The Saola Or Spindlehorn Bovid Pseudoryx Nghetinhensis in Laos

ORYX VOL 29 NO 2 APRIL 1995 The saola or spindlehorn bovid Pseudoryx nghetinhensis in Laos George B. Schaller and Alan Rabinowitz In 1992 the discovery of a new bovid, Pseudoryx nghetinhensis, in Vietnam led to speculation that the species also occurred in adjacent parts of Laos. This paper describes a survey in January 1994, which confirmed the presence of P. ngethinhensis in Laos, although in low densities and with a patchy distribution. The paper also presents new information that helps clarify the phylogenetic position of the species. The low numbers and restricted range ofP. ngethinhensis mean that it must be regarded as Endangered. While some admirable moves have been made to protect the new bovid and its habitat, more needs to be done and the authors recommend further conservation action. Introduction area). Dung et al. (1994) refer to Pseudoryx as the Vu Quang ox, but, given the total range of In May 1992 Do Tuoc and John MacKinnon the animal and its evolutionary affinities (see found three sets of horns of a previously un- below), we prefer to call it by the descriptive described species of bovid in the Vu Quang local name 'saola'. Nature Reserve of west-central Vietnam The village of Nakadok, where saola horns (Stone, 1992). The discovery at the end of the were found, lies at the end of the Nakai-Nam twentieth century of a large new mammal in a Theun National Biodiversity Conservation region that had been visited repeatedly by sci- Area (NNTNBCA), which at 3500 sq km is the entific and other expeditions (Delacour and largest of 17 protected areas established by Jabouille, 1931; Legendre, 1936) aroused in- Laos in October 1993. -

Volatile Cues Influence Host-Choice in Arthropod Pests

animals Review Volatile Cues Influence Host-Choice in Arthropod Pests Jacqueline Poldy Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Health & Biosecurity, Black Mountain Laboratory, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; [email protected]; Tel.: +61-2-6218-3599 Received: 1 October 2020; Accepted: 22 October 2020; Published: 28 October 2020 Simple Summary: Many significant human and animal diseases are spread by blood feeding insects and other arthropod vectors. Arthropod pests and disease vectors rely heavily on chemical cues to identify and locate important resources such as their preferred animal hosts. Although there are abundant studies on the means by which biting insects—especially mosquitoes—are attracted to humans, this focus overlooks the veterinary and medical importance of other host–pest relationships and the chemical signals that underpin them. This review documents the published data on airborne (volatile) chemicals emitted from non-human animals, highlighting the subset of these emissions that play a role in guiding host choice by arthropod pests. The paper exposes some of the complexities associated with existing methods for collecting relevant chemical features from animal subjects, cautions against extrapolating the ecological significance of volatile emissions, and highlights opportunities to explore research gaps. Although the literature is less comprehensive than human studies, understanding the chemical drivers behind host selection creates opportunities to interrupt pest attack and disease transmission, enabling more efficient pest management. Abstract: Many arthropod pests of humans and other animals select their preferred hosts by recognising volatile odour compounds contained in the hosts’ ‘volatilome’. Although there is prolific literature on chemical emissions from humans, published data on volatiles and vector attraction in other species are more sporadic. -

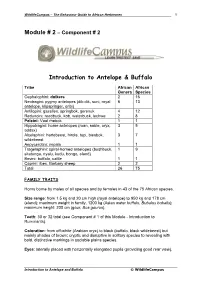

Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo

WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 1 Module # 2 – Component # 2 Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo Tribe African African Genera Species Cephalophini: duikers 2 16 Neotragini: pygmy antelopes (dik-dik, suni, royal 6 13 antelope, klipspringer, oribi) Antilopini: gazelles, springbok, gerenuk 4 12 Reduncini: reedbuck, kob, waterbuck, lechwe 2 8 Peleini: Vaal rhebok 1 1 Hippotragini: horse antelopes (roan, sable, oryx, 3 5 addax) Alcelaphini: hartebeest, hirola, topi, biesbok, 3 7 wildebeest Aepycerotini: impala 1 1 Tragelaphini: spiral-horned antelopes (bushbuck, 1 9 sitatunga, nyalu, kudu, bongo, eland) Bovini: buffalo, cattle 1 1 Caprini: ibex, Barbary sheep 2 2 Total 26 75 FAMILY TRAITS Horns borne by males of all species and by females in 43 of the 75 African species. Size range: from 1.5 kg and 20 cm high (royal antelope) to 950 kg and 178 cm (eland); maximum weight in family, 1200 kg (Asian water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis); maximum height: 200 cm (gaur, Bos gaurus). Teeth: 30 or 32 total (see Component # 1 of this Module - Introduction to Ruminants). Coloration: from off-white (Arabian oryx) to black (buffalo, black wildebeest) but mainly shades of brown; cryptic and disruptive in solitary species to revealing with bold, distinctive markings in sociable plains species. Eyes: laterally placed with horizontally elongated pupils (providing good rear view). Introduction to Antelope and Buffalo © WildlifeCampus WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 2 Scent glands: developed (at least in males) in most species, diffuse or absent in a few (kob, waterbuck, bovines). Mammae: 1 or 2 pairs. Horns. True horns consist of an outer sheath composed mainly of keratin over a bony core of the same shape which grows from the frontal bones. -

GUIDES NEWSLETTER JULY 2019 Written by Isaiah Banda

GUIDES NEWSLETTER JULY 2019 Written By Isaiah Banda The mercury dropped to 3.1 degrees Celsius in the beginning of the month until mid-month here at Safari Plains. Different days of the month it was only at 3.6, but different parts of the reserve experience slight temperature variations, as down in the western side of the lodge was the coldest I’ve felt in a couple of years, and I was in different areas on the reserve during the month, when it didn’t feel as bad. I’m confident it was only just above freezing in some of the depressions this month. I was in a sighting with the Madjuma pride but was particularly loathed to take off my gloves to work the camera, as I knew the kind of pain they would be in within seconds. Not cold… pain! Luckily, I had a company of Riette Smit, she did not hesitate to take her camera out. WWW.SAFARIPLAINS.CO.ZA Invariably in the mornings, the first hour of the drive is quiet. Predators aren’t moving around quite as much, probably conserving energy. It’s usually only when the temperature starts to rise that the action starts, and suddenly the tracking efforts start finding success, and the number of sightings starts to spike. The bush has essentially followed that pattern for the past month; we leave the lodge before sunrise bundled up in at least four layers, numb our faces for an hour or so until we start speaking incoherently, and then just as it’s almost time for a warm cup of coffee, outcomes the wildlife! Curiosity Killed the…. -

FASTEST ANIMALS and WYOMING ICON

TAKE A CLOSE-UP LOOK AT ONE OF THE WORLD’S FASTEST ANIMALS and WYOMING ICON Tom Reichner at shutterstock.com 4 BARNYARDS & BACKYARDS Abby Perry form of fat for demanding times like he pronghorn is a Wyoming the end of gestation and lactation. icon. Other animals are considered in- T They use their long hair to com- Its image appears on business come breeders. They use energy as municate danger to other members signs, public art, and even agency they acquire it, and have much less of the herd. They raise the hair on emblems, and hearing Wyomingites energy stored; some do not store their rump as a warning of danger, a brag there are more pronghorn in energy at all. characteristic that has, perhaps, con- Wyoming than people is not uncom- Pronghorn are in-between capital tributed to their survival. Pronghorn mon. We love that over half of the and income breeders, but likely fall are the last remaining species of their worldwide pronghorn population is more on the income breeder side of family, Antilocpridae, and are most within the state. the spectrum. They have very few closely related to giraffes. Pronghorn populations no longer fat stores, which is interesting con- Pronghorn horns have branches exceed the population of Wyoming. sidering some of their reproductive and have a bony core like a true horn, Numbers have decreased significant- characteristics. but they also have a branching horn ly over the last couple of decades and Pronghorn invest more highly in sheath that is shed every year like an are close to 400,000.