Sacred Music Volume 126 Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raffael Santi | Elexikon

eLexikon Bewährtes Wissen in aktueller Form Raffael Santi Internet: https://peter-hug.ch/lexikon/Raffael+Santi MainSeite 63.593 Raffael Santi 3'315 Wörter, 22'357 Zeichen Raffael Santi, auch Rafael, Raphael (ital. Raffaello), irrtümlich Sanzio,ital. Maler, geb. 1483 zu Urbino. Der Geburtstag selbst ist streitig: je nachdem man die vom Kardinal Bembo verfaßte Grabschrift R.s deutet, welche besagt, er sei «an dem Tage, an dem er geboren war, gestorben» («quo die natus est eo esse desiit VIII Id. April MDXX», d. i. 6. April 1520, damals Karfreitag), setzt man den Geburtstag auf den 6. April oder auf den Karfreitag, d. i. 28. März 1483, an. Seine erste künstlerische Unterweisung dankte er dem Vater Giovanni Santi (s. d.), den er jedoch bereits im 12. Jahre verlor, sodann einem unbekannten Meister in Urbino, vielleicht dem Timoteo Viti, mit dem er auch später enge Beziehungen unterhielt. Erst 1499 verließ er die Vaterstadt und trat in die Werkstätte des damals hochberühmten Malers Perugino (s. d.) in Perugia. Das älteste Datum, welches man auf seinen Bildern antrifft, ist das Jahr 1504 (auf dem «Sposalizio», s. unten); doch hat er gewiß schon früher selbständig für Kirchen in Perugia und in Città di Castello gearbeitet. 1504 siedelte Raffael Santi nach Florenz über, wo er die nächsten Jahre mit einigen Unterbrechungen, die ihn nach Perugia und Urbino zurückführten, verweilte. In Florenz war der Einfluß Leonardos und Fra Bartolommeos auf seine künstlerische Vervollkommnung am mächtigsten; von jenem lernte er die korrekte Zeichnung, von diesem den symmetrischen und dabei doch bewegten Aufbau der Figuren. Als abschließendes künstlerisches Resultat seines Aufenthalts in Florenz ist die 1507 für San Fancesco in Perugia gemalte Grablegung zu betrachten (jetzt in der Galerie Borghese zu Rom). -

RAFFAELLO SANZIO Una Mostra Impossibile

RAFFAELLO SANZIO Una Mostra Impossibile «... non fu superato in nulla, e sembra radunare in sé tutte le buone qualità degli antichi». Così si esprime, a proposito di Raffaello Sanzio, G.P. Bellori – tra i più convinti ammiratori dell’artista nel ’600 –, un giudizio indicativo dell’incontrastata preminenza ormai riconosciuta al classicismo raffaellesco. Nato a Urbino (1483) da Giovanni Santi, Raffaello entra nella bottega di Pietro Perugino in anni imprecisati. L’intera produzione d’esordio è all’insegna di quell’incontro: basti osservare i frammenti della Pala di San Nicola da Tolentino (Città di Castello, 1500) o dell’Incoronazione di Maria (Città del Vaticano, Pinacoteca Vaticana, 1503). Due cartoni accreditano, ad avvio del ’500, il coinvolgimento nella decorazione della Libreria Piccolomini (Duomo di Siena). Lo Sposalizio della Vergine (Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera, 1504), per San Francesco a Città di Castello (Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera), segna un decisivo passo di avanzamento verso la definizione dello stile maturo del Sanzio. Il soggiorno a Firenze (1504-08) innesca un’accelerazione a tale processo, favorita dalla conoscenza dei tra- guardi di Leonardo e Michelangelo: lo attestano la serie di Madonne con il Bambino, i ritratti e le pale d’altare. Rimonta al 1508 il trasferimento a Roma, dove Raffaello è ingaggiato da Giulio II per adornarne l’appartamento nei Palazzi Vaticani. Nella prima Stanza (Segnatura) l’urbinate opera in autonomia, mentre nella seconda (Eliodoro) e, ancor più, nella terza (Incendio di Borgo) è affiancato da collaboratori, assoluti responsabili dell’ultima (Costantino). Il linguaggio raffaellesco, inglobando ora sollecitazioni da Michelangelo e dal mondo veneto, assume accenti rilevantissimi, grazie anche allo studio dell’arte antica. -

Some Striking

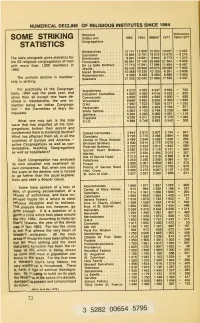

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

The Premonstratensian Project

Chapter 7 The Premonstratensian Project Carol Neel 1 Introduction The order of Prémontré, in the hundred years after the foundation of its first religious community in 1120, instantiated the vibrant religious enthusiasm of the long twelfth century. Like other religious orders originating in the medieval reformation of Catholic Christianity, the Premonstratensians looked to the early church for their inspiration, but to the rule of Augustine rather than to the rule of Benedict whose reinterpretation defined the still more numerous and influential Cistercians.1 The Premonstratensian framers, in the first in- stance their founder Norbert of Xanten (d. 1134), understood the Augustinian rule to have been composed by the ancient bishop for his own community of priests in Hippo, hence believed it the most ancient and venerable of constitu- tions for intentional religious life in the Latin-speaking West.2 As Regular Can- ons ordained to priesthood and living together in community under the rule of Augustine rather than monks according to a reformed Benedictine model, the Premonstratensians were then both primitivist and innovative. While the or- der of Prémontré embraced the novelty of its own project in interpreting the Augustinian ideal for a Europe reshaped by Gregorian Reform, burgeoning lay piety, and a Crusader spirit, at the same time it homed to an ancient paradigm of a priesthood informed and inspired by the sharing of poverty and prayer. Among numerous contemporaneous reform movements and religious com- munities claiming return to apostolic values, the medieval Premonstratensians thus maintained a vivid consciousness of the distinctiveness of their charism as a mixed apostolate bringing together contemplative retreat and active en- gagement in the secular world. -

Raffaelloraffaello

RAFFAELLORAFFAELLO Autoritratto, 1506 ca Vol II, pp. 446-459 1483-1520 LA VITA 1483 nasce a Urbino figlio di un pittore Va a bottega dal padre e si educa alla corte dei Montefeltro Allievo del Perugino 1504-1508 soggiorno fiorentino 1508 va a Roma invitato da Giulio II e con l’aiuto di Bramante Lavora per Giulio II e Leone X 1520 muore a Roma Raffaello 2 1483-1520 LE OPERE 1500-1502 Studio di nudo maschile (disegno) Urbino 1502 Cristo benedicente 1505 San Giorgio e il drago (disegno) Firenze 1504 Lo sposalizio della Vergine (olio su tavola) 1505 Ritratto di Agnolo Doni 1506 Ritratto di Maddalena Doni 1506 Madonna del cardellino 1506 Madonna del prato (o del Belvedere) 1507 Sacra famiglia Canigiani (olio su tavola) 1507-1509 Trasporto di Cristo al sepolcro (pala Baglioni) 1509-1510 Scuola d’Atene (affresco) Roma 1512 Ritratto di Giulio II 1513 Madonna della seggiola 1513 La velata 1513-1514 altri affreschi nelle Stanze vaticane 1518 Leone X 1518-1519 Due uomini nudi in piedi (disegno) 1518-1520 Trasfigurazione (olio su tavola) Raffaello 3 1500-1502 STUDIO DI NUDO MASCHILE All’inizio della sua carriera si dedica al disegno, soprattutto agli studi sulla figura umana Non disegna un contorno netto ma una serie di linee affiancate I corpi vengono presentati scarni, con muscoli e tendini in evidenza Michelangelo, Studio di figura nuda, 1504-06 Raffaello 4 1502 CRISTO BENEDICENTE Opera giovanile È ancora a Urbino Raffaello 5 1505 SAN GIORGIO E IL DRAGO Influssi leonardeschi – Il cavallo impennato – Lo slancio del cavaliere – La lunga testa del -

Being Seen: an Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia J

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College History Honors Projects History Department Spring 4-21-2011 Being Seen: An Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia J. Belote Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/history_honors Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Other Applied Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Belote, Olivia J., "Being Seen: An Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome" (2011). History Honors Projects. Paper 9. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/history_honors/9 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Being Seen: An Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia Joy Belote Honors Project, History 2011 1 History Honors 2011 Advisor: Peter Weisensel Second Readers: Kristin Lanzoni and Susanna Drake Contents Page Introduction..................................................................................................................3 Feminist History and Females in Christianity..............................................................6 The -

SPIRITUALITY: ABCD's “Catholic Spirituality” This Work Is a Study in Catholic Spirituality. Spirituality Is Concerned With

SPIRITUALITY: ABCD’s “Catholic Spirituality” This work is a study in Catholic spirituality. Spirituality is concerned with the human subject in relation to God. Spirituality stresses the relational and the personal though does not neglect the social and political dimensions of a person's relationship to the divine. The distinction between what is to be believed in the do- main of dogmatic theology (the credenda) and what is to be done as a result of such belief in the domain of moral theology (the agenda) is not always clear. Spirituality develops out of moral theology's concern for the agenda of the Christian life of faith. Spirituality covers the domain of religious experience of the divine. It is primarily experiential and practical/existential rather than abstract/academic and conceptual. Six vias or ways are included in this compilation and we shall take a look at each of them in turn, attempting to highlight the main themes and tenets of these six spiritual paths. Augustinian Spirituality: It is probably a necessary tautology to state that Augus- tinian spirituality derives from the life, works and faith of the African Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430). This spirituality is one of conversion to Christ through caritas. One's ultimate home is in God and our hearts are restless until they rest in the joy and intimacy of Father, Son and Spirit. We are made for the eternal Jerusalem. The key word here in our earthly pilgrimage is "conversion" and Augustine describes his own experience of conversion (metanoia) biographically in Books I-IX of his Confessions, a spiritual classic, psychologically in Book X (on Memory), and theologically in Books XI-XIII. -

Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century

A “Truly Unmonastic Way of Life”: Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hannah Elizabeth Ewing Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Timothy Gregory, Advisor Professor Anthony Kaldellis Professor Alison I. Beach Copyright by Hannah Elizabeth Ewing 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines twelfth-century Byzantine writings on monasticism and holy men to illuminate monastic critiques during this period. Drawing upon close readings of texts from a range of twelfth-century voices, it processes both highly biased literary evidence and the limited documentary evidence from the period. In contextualizing the complaints about monks and reforms suggested for monasticism, as found in the writings of the intellectual and administrative elites of the empire, both secular and ecclesiastical, this study shows how monasticism did not fit so well in the world of twelfth-century Byzantium as it did with that of the preceding centuries. This was largely on account of developments in the role and operation of the church and the rise of alternative cultural models that were more critical of traditional ascetic sanctity. This project demonstrates the extent to which twelfth-century Byzantine society and culture had changed since the monastic heyday of the tenth century and contributes toward a deeper understanding of Byzantine monasticism in an under-researched period of the institution. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family, and most especially to my parents. iii Acknowledgments This dissertation is indebted to the assistance, advice, and support given by Anthony Kaldellis, Tim Gregory, and Alison Beach. -

Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar | Epicurean Traveler

Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar | Epicurean Traveler https://epicurean-traveler.com/rome-celebrates-raphael-superstar/?... U a Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar by Lucy Gordan | Travel | 0 comments Self-portrait of Raphael with an unknown friend This year the world is celebrating the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death with exhibitions in London at both the National Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, in Paris at the Louvre, and in Washington D.C. at the National Gallery. However, the mega-show, to end all shows, is “Raffaello 1520-1483” which opened on March 5th and is on until June 2 in Rome, where Raphael lived the last 12 years of his short life. Since January 7th over 70,000 advance tickets sales from all over the world have been sold and so far there have been no cancellations in spite of coronavirus. Not only is Rome an appropriate location, but so are the Quirinal’s scuderie or stables, as the Quirinal was the summer palace of the popes, then the home of Italy’s Royal family and now of its President. On display are 240 works-of-art; 120 of them (including the Tapestry of The Sacrifice of Lystra based on his cartoons and his letter to Medici-born Pope Leo X (reign 1513-21) about the importance of preserving Rome’s antiquities) are by Raphael himself. Twenty- 1 of 9 3/6/20, 3:54 PM Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar | Epicurean Traveler https://epicurean-traveler.com/rome-celebrates-raphael-superstar/?... seven of these are paintings, the others mostly drawings. Never before have so many works by Raphael been displayed in a single exhibition. -

A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (With Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia)

religions Article A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia) Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig Jakobsen Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics, University of Copenhagen, 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] Abstract: Monasticism was introduced to Denmark in the 11th century. Throughout the following five centuries, around 140 monastic houses (depending on how to count them) were established within the Kingdom of Denmark, the Duchy of Schleswig, the Principality of Rügen and the Duchy of Estonia. These houses represented twelve different monastic orders. While some houses were only short lived and others abandoned more or less voluntarily after some generations, the bulk of monastic institutions within Denmark and its related provinces was dissolved as part of the Lutheran Reformation from 1525 to 1537. This chapter provides an introduction to medieval monasticism in Denmark, Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia through presentations of each of the involved orders and their history within the Danish realm. In addition, two subchapters focus on the early introduction of monasticism to the region as well as on the dissolution at the time of the Reformation. Along with the historical presentations themselves, the main and most recent scholarly works on the individual orders and matters are listed. Keywords: monasticism; middle ages; Denmark Citation: Jakobsen, Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig. 2021. A Brief For half a millennium, monasticism was a very important feature in Denmark. From History of Medieval Monasticism in around the middle of the 11th century, when the first monastic-like institutions were Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and introduced, to the middle of the 16th century, when the last monasteries were dissolved Estonia). -

Psalter (Premonstratensian Use) in Latin, Illuminated Manuscript on Parchment, with (Added) Musical Notation Northwestern Germany (Diocese of Cologne), C

Psalter (Premonstratensian use) In Latin, illuminated manuscript on parchment, with (added) musical notation Northwestern Germany (diocese of Cologne), c. 1270-1280 270 folios on parchment, modern foliation in pencil, 1-270, complete (collation i13 [quire of 12 with a singleton added at the end] ii-xx12 xxi10 [-10, cancelled blank after f. 250] xxii-xxiii8 xxiv4), no catchwords or signatures, ruled in brown ink until f. 250 (justification 74 x 47 mm.), written by three different scribes in brown ink in gothic textualis bookhand on 17 lines, originally the manuscript included quires 1-xxi, ff. 1-250, in the early fourteenth century new texts were added on the space left blank on ff. 248v-250v and on the added leaves (not ruled), prickings visible in the outer margins, 2-line initials in red or blue with contrasting penwork flourishing beginning psalms and other texts, twenty- one 3- to 6-line initials in burnished gold on grounds painted in dark pink and blue decorated with white penwork, ONE ILLUMINATED INITIAL, 7-lines, opening the psalms, chants added in the margins in fourteenth-century textualis hand and hufnagelschrift notation, a small tear in the outer margin of f. 173, occasional flaking of the pigment and gold of initials, thumbing, otherwise in excellent condition. Bound in the sixteenth century in calf over wooden boards blind-tooled with a roll with heads in profile, lacking clasps and catches, worn at joints, otherwise in excellent condition. Dimensions 103 x 75 mm. Charming example of an illuminated liturgical Psalter, certainly owned by women in the seventeenth century, and perhaps made for Premonstratensian nuns. -

The Early Privileges of the Society of Jesus 1537 to 1556

Concessions, communications, and controversy: the early privileges of the Society of Jesus 1537 to 1556 Author: Robert Morris Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108457 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2019 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Concessions, Communications and Controversy: The Early Privileges of the Society of Jesus 1537 to 1556. Partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Licentiate in Sacred Theology Robert Morris, S.J. Readers Dr. Catherine M. Mooney Dr. Barton Geger, S.J. Boston College 2019 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE: THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF RELIGIOUS PRIVILEGES ................ 6 ORIGINS: PRIVILEGES IN ROMAN LAW .................................................................................................................. 6 THE PRIVILEGE IN MEDIEVAL CANON LAW ......................................................................................................... 7 Mendicants ........................................................................................................................................................... 12 Developments in the Canon Law of Privileges in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries ... 13 Further distinctions and principles governing privileges ...............................................................