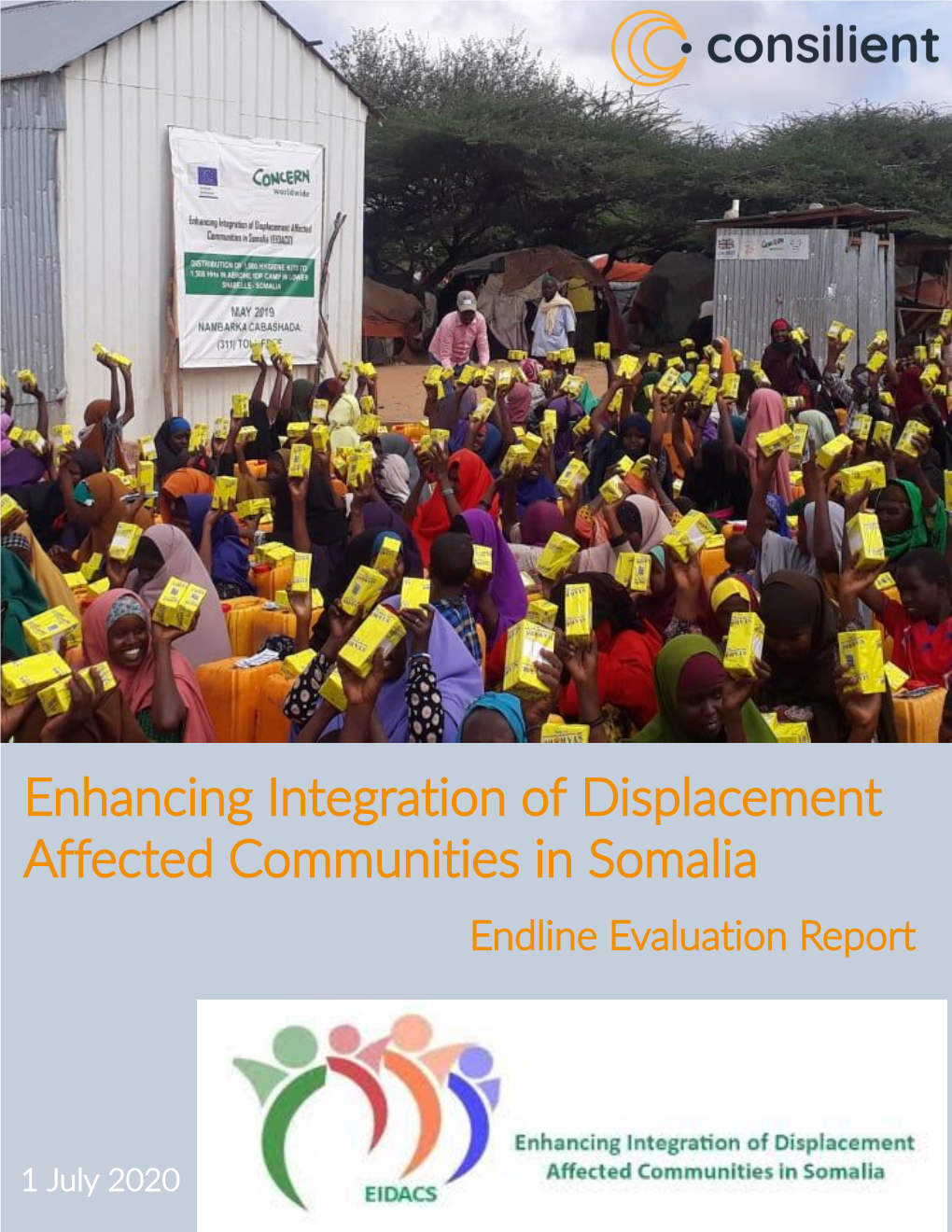

Enhancing Integration of Displacement Affected Communities in Somalia Endline Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somali Democratic Republic Ministry of Agriculture

Somali Democratic Republic Ministry of Agriculture Directorate of Planning and-Training /Food Security Project "Maize Supply and Price Situation in Somalia: An Historical Overview zond Analysis of Recent Char.oes by John S. Holtzwan WORKING PAPER No. 5 May 1987. Working Paper Series MAIZE SUPPLY AND PRICE SITUATION IN SOMALIA: AN HISTOR:CAL OVERVIEW A,'D ANALYSIS OF RECEMT CHANGF.51 John S. Holtzman Food Security Project, MOA/MSU 1.0 Introduction Maize is a basic staple in southern Somalia, whose output has expanded luring the past decada. The available official statistics suigest tiat Somali producers have cultivated more land to maizu U'uring the 1980s than during the 1970s. Aggregate moize production has expanded, while sorghum production has stagnated. Maize yields appear to have risen more rapidly than sorghum yields. tuiorts have fluctuated considerably, depending on overall availability of food grains in particular years. What are the factori that have contributed to increased maize output in Somalia- How important have rainfall, market liberalization, and -'eal price trends been in the expansion of taize prouction Pnd stagnation of sorghum prodUction? The objectives of this paper are thrcefold. First, it will present and discuss the av.i lable data on the maize supply and rice situation in Somalia, with special focus on changes in the 1980s (section 2.0). Second, the paper kill examine factors contributing to maize expansion (section 3.0). Last, it will assess in a preliminary way the possibility and opportunity for continued expansion in maip output (section 4.0). 2.0 Mzize Supoly and Price Situation in the 11B0s 2.1 Inconsistent Data: The Food Security Analyst's Dilemma In Somalia, as in many African countries, thi available sources .-f cereali production and impprt data are not always consistent. -

Somali Republic Ministry of Education, Culture & Higher

National Education Plan Somali Republic Ministry of Education, Culture & Higher Education National Education Plan. May 2011 1 National Education Plan Preface The collapse of central government of Somalia in 1991 and the civil war that erupted and the continues foreign intervention has caused total destruction of national institution especially those who were providing services to our citizen like health, education, water ad electricity institutions. The destruction has affected the economics of the country both Public and private properties. The country has became a place where there is no law and order and insecurity prevailed and killing, looting and displacement has become day to day with the live of Somalis. The ministry of education, culture and higher education and its department was among the sectors that were spared that resulted total closure of all offices and centers that was dealing with education services and most of education staffs left the country as refugees. It was early 1992, when Somali educationalists regrouped again to revive the education sector of the country to provide the education service that our people used to get from the national education institution that was not functioning at all. Education umbrellas, privately owned school, colleges and higher education institutions have been established to cover the services that the ministry of education was providing to the people before 1991. But again this effort could not provide quality free education throughout the country. The role of the international and local organization towards the education sector of Somalia together with the support of citizens has made the sector with little improved. -

A Moder N H O F Soma

COLLO... :,<.,r;: cc r i -J I.- .. P*!,!, REVISED, UPDATED, AND EXPANDED EDITION lì. A MODERN HISTORY OF SOMALIA Natlon and State in thè Horn of Africa I. M. LEWIS, Westview Press ^'5?x BOULDER & LONDON >^'*. \ K:%: jv^i -/ / o/ • /.-Ay v>; CONTENTS Preface to che 1988 Editìon vii Preface to thè First Edition ix Chapter I The Physica! and Social Setting 1 II Ecfore Partition 18 This Westview softcover editìon il printed un aud-frue pnper and bound in softcovecs thac III The Imperiai Partition: 1860-97 40 curry thè bighe» rating of thè National Aurxìation of State Textbook Adminìstracors, in tons» Iration wich thè Association of American Publiihcrs and thè Hook Manu faci uters' IV The Dervish Fight for Freedom: 1900-20 63 Inscitutf. V Somali Unificatìon: The Italian East*Afrìcan Empire Ali rights reserved. No pare of chis publkarion may be reproduced oc transmitted in any 92 forni or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, rccording, or any in for m uri un Storage and retrieva! System, wichout pcrmìssion in wticing from thè publisher. VI The Restoration of Colonial Frontiere: 1940-50 116 Copyright © 1965, 1980, 1988 by I. M. Lewis VII From Trusteeship to Independence: 1950-60 139 Vili The Problems of Independence Fine published in thè United States of America in 1988 by Wesrvicw Press, Inc.; Frederick 166 Prjegcr, Publisher, 5500 Cenerai Avenue, Boulder, Colorado 80301 A. IX The Somali Revolution: 1969-76 205 First edìtion published in 1980 by Longman Group Limited; chapters 1 through 8 published X Nationalism, Ethnicity and Revolution in thè in 1965 by Weidenfeld ;»nd Nkolson Horn of Africa 226 Maps Library of Congress CaraJoging-in-PublicatÌon Data 267 Lewis, I. -

SOMALIË Veiligheidssituatie in Mogadishu

COMMISSARIAAT-GENERAAL VOOR DE VLUCHTELINGEN EN DE STAATLOZEN COI Focus SOMALIË Veiligheidssituatie in Mogadishu 21 april 2020 (update) Cedoca Oorspronkelijke taal: Nederlands DISCLAIMER: Dit COI-product is geschreven door de documentatie- en researchdienst This COI-product has been written by Cedoca, the Documentation and Cedoca van het CGVS en geeft informatie voor de behandeling van Research Department of the CGRS, and it provides information for the individuele verzoeken om internationale bescherming. Het document bevat processing of individual applications for international protection. The geen beleidsrichtlijnen of opinies en oordeelt niet over de waarde van het document does not contain policy guidelines or opinions and does not pass verzoek om internationale bescherming. Het volgt de richtlijnen van de judgment on the merits of the application for international protection. It follows Europese Unie voor de behandeling van informatie over herkomstlanden van the Common EU Guidelines for processing country of origin information (April april 2008 en is opgesteld conform de van kracht zijnde wettelijke bepalingen. 2008) and is written in accordance with the statutory legal provisions. De auteur heeft de tekst gebaseerd op een zo ruim mogelijk aanbod aan The author has based the text on a wide range of public information selected zorgvuldig geselecteerde publieke informatie en heeft de bronnen aan elkaar with care and with a permanent concern for crosschecking sources. Even getoetst. Het document probeert alle relevante aspecten van het onderwerp though the document tries to cover all the relevant aspects of the subject, the te behandelen, maar is niet noodzakelijk exhaustief. Als bepaalde text is not necessarily exhaustive. If certain events, people or organisations gebeurtenissen, personen of organisaties niet vernoemd worden, betekent dit are not mentioned, this does not mean that they did not exist. -

UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery in Somalia JPLG Annual Report 2013

UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery in Somalia JPLG Annual Report 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of JPLG Target Districts ................................................................................................................... 2 Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 JPLG Resources Summary: 2013 – 2017 .................................................................................................. 5 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 6 Outcome 1: Policy and Legal Development .............................................................................................. 8 Outcome 2: Capacity Development ........................................................................................................... 8 Outcome 3: Service Delivery ...................................................................................................................... 9 PROGRESS AGAINST THEMATIC AREAS AND OUTPUTS: ....................................................... 11 CHAPTER ONE: POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................... 11 CHAPTER TWO: CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT .............................................................................. 27 CHAPTER THREE: CONFLICT SENSITIVITY AND RISK MANAGEMENT .......................... -

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki District 2 Awdal Region Borama District 3 Awdal Region Lughaya District 4 Awdal Region Zeila District 5 Bakool Region El Barde District 6 Bakool Region Hudur District 7 Bakool Region Rabdhure District 8 Bakool Region Tiyeglow District 9 Bakool Region Wajid District 10 Banaadir Region Abdiaziz District 11 Banaadir Region Bondhere District 12 Banaadir Region Daynile District 13 Banaadir Region Dharkenley District 14 Banaadir Region Hamar Jajab District 15 Banaadir Region Hamar Weyne District 16 Banaadir Region Hodan District 17 Banaadir Region Hawle Wadag District 18 Banaadir Region Huriwa District 19 Banaadir Region Karan District 20 Banaadir Region Shibis District 21 Banaadir Region Shangani District 22 Banaadir Region Waberi District 23 Banaadir Region Wadajir District 24 Banaadir Region Wardhigley District 25 Banaadir Region Yaqshid District 26 Bari Region Bayla District 27 Bari Region Bosaso District 28 Bari Region Alula District 29 Bari Region Iskushuban District 30 Bari Region Qandala District 31 Bari Region Ufayn District 32 Bari Region Qardho District 33 Bay Region Baidoa District 34 Bay Region Burhakaba District 35 Bay Region Dinsoor District 36 Bay Region Qasahdhere District 37 Galguduud Region Abudwaq District 38 Galguduud Region Adado District 39 Galguduud Region Dhusa Mareb District 40 Galguduud Region El Buur District 41 Galguduud Region El Dher District 42 Gedo Region Bardera District 43 Gedo Region Beled Hawo District www.downloadexcelfiles.com 44 Gedo Region El Wak District 45 Gedo -

PDF-Dokument

25.10.2017 Gericht BVwG Entscheidungsdatum 25.10.2017 Geschäftszahl W211 2123797-1 Spruch W211 2123797-1/24E IM NAMEN DER REPUBLIK! Das Bundesverwaltungsgericht erkennt durch die Richterin Mag.a SIMMA als Einzelrichterin über die Beschwerde von XXXX , geboren am XXXX , StA. Somalia, gegen Spruchpunkt I. des Bescheids des Bundesamtes für Fremdenwesen und Asyl vom XXXX , nach Durchführung einer mündlichen Verhandlung zu Recht: A) Der Beschwerde wird gemäß § 28 Abs. 2 VwGVG stattgegeben und XXXX gemäß § 3 Abs. 1 AsylG 2005 der Status eines Asylberechtigten zuerkannt. Gemäß § 3 Abs. 5 AsylG 2005 wird festgestellt, dass XXXX damit kraft Gesetzes die Flüchtlingseigenschaft zukommt. B) Die Revision ist gemäß Art. 133 Abs. 4 B-VG nicht zulässig. Text ENTSCHEIDUNGSGRÜNDE: I. Verfahrensgang: 1. Die beschwerdeführende Partei, ein männlicher Staatsangehöriger Somalias, stellte am XXXX .2015 einen Antrag auf internationalen Schutz in Österreich. 2. Bei ihrer Erstbefragung durch Organe des öffentlichen Sicherheitsdienstes am XXXX .2015 gab die beschwerdeführende Partei an, aus dem Ort XXXX -Marka zu kommen und den Dir anzugehören. Sie habe ihr Land aufgrund einer persönlichen Bedrohung durch die Terrororganisation Al Shabaab verlassen. Diese habe ihren Vater 2013 getötet und ihren Bruder entführt. Sie selbst habe daher Angst gehabt, ebenfalls von der Gruppe entführt zu werden. 3. Bei der Einvernahme durch die belangte Behörde am XXXX .2016 gab die beschwerdeführende Partei zusammengefasst und ergänzend an, dass sie verheiratet sei und zwei Kinder habe. Ihre Frau, ihre Kinder, drei Geschwister und eine Tante würden noch im Dorf XXXX -Marka leben. Ihr Vater sei 2013 getötet worden, und ihre Mutter sei zuvor schon verstorben. Die beschwerdeführende Partei habe dann das Lokal des Vaters gemeinsam mit ihrer Tante weitergeführt. -

Agulhas and Somali Currents Large Marine Ecosystems Project

Agulhas and Somali Currents Large Marine Ecosystems Project Capacity Building and Training Component National Training Plan for SOMALIA Prepared by: Mr. Hassan Mohamud Nur 1) Summary of key training requirements a) Skill training for fishers. b) To strength the scientific and management expertise c) To introduce an ecosystem approach to managing the living marine resources d) To enhance the local and international markets. e) To secure processing systems f) To upgrade environmental awareness and waste management and marine pollution control g) To create linkages between the local community and the international agencies 2) introduction: Somalia has 3,333Km of coast line of which 2,000Km is in the Indian Ocean south of Cape Guardafui and 1,333Km of north shore of Gulf of Aden. Surveys indicate high potential for fisheries development with evenly distributed fish stocks along the entire coastline, but with greater concentration in the Northeast. The fishing seasons are governed by two monsoon winds, the south west monsoon during June to September and northeast monsoon during December to March and two inter-monsoon periods during April/May and October/November. In the case of Somalia, for the last two decades the number of people engaged in fisheries has increased from both the public and private sector. Although, the marine fisheries potential is one of the main natural resources available to the Somali people, there is a great need to revive the fisheries sector and rebuild the public and private sector in order to promote the livelihood of the Somali fishermen and their families. 3) Inventory of current educational Capacity Somalia has an increasing number of elementary and intermediate schools, beside a number of secondary and a handful of universities. -

Somalia Hagaa Season Floods Update 2 As of 26 July 2020

Somalia Hagaa Season Floods Update 2 As of 26 July 2020 Highlights • Flash and riverine floods have since late June affected an estimated 191,800 people in Hirshabelle, South West and Jubaland states as well as Banadir region. • Among those affected, about 124,200 people have been displaced from their homes. Another 5,000 peope are at risk of further displacement in Jowhar, Middle Shabelle. • Since May, an estimated 149,000 hectares of farmland have been damaged by floods in 100 villages in Jowhar, Mahaday and Balcad districts, Middle Shabelle region. • Humanitarian partners have scaled up responses, but major gaps remain particularly in regard to food, WASH, shelter and non-food items, health services and protection assistance. Situation overview The number of people affected by flash and riverine floods since late June in Hirshabelle, South West, Jubaland states and Banadir region has risen to 191,800, of whom 124,200 people have been displaced from their homes, according to various rapd asessments. Hirshabelle and South West States are the worst affected, accounting for nearly 91 per cent of the caseload (164,000 people). Humanitarian needs are rising among those affected, even as partners ramp up assistance. The floods have been triggered by heavy downpours during the current Hagaa ‘dry’ season. SWALIM1 forecasts that flooding in the middle and lower reaches of the Shabelle will continue in the coming week especially in Jowhar town and surrounding areas, due to anticipated moderate to heavy rains. In Hirshabelle, flash and riverine floods displaced at least 66,000 people and damaged 33,000 hectares of farmland in Balcad district, Middle Shabelle region, between 24 June and 15 July, according to joint assessment conducted on 21 July by humanitarian partners and authorities. -

Stories from Girls and Women of Mogadishu

Stories from Girls and Women of Mogadishu Stories from Girls and Women of Mogadishu “Stories from Girls and Women of Mogadishu” Edition 2017/2 Published by CISP – Comitato Internazionale per lo Sviluppo dei Popoli (International Committee for the Development of People) – Nairobi Idea and Supervision: Rosaia Ruberto Project Coordination: Francesco Kaburu Development and Editing: Jessica Buchleitner Co-Editor: Sagal Ali Proofreading: Nancee Adams-Taylor Translators from Somali: Tubali Ltd Editorial Coordination: Chiara Camozzi, Xavier Verhoest Design: Annia Arosa Martinez Photos: Abdulkadir Mohamed (Ato), Xavier Verhoest Printing: Executive Printing Works Ltd, Nairobi © CISP, 2017 - Stories from Girls and Women of Mogadishu. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be shared upon being given prior permission from the editors and the authors. Please write to us: [email protected]. Contents Definitions ................................................................................I CHAPTER FIVE: A Model Citizen .................................................102 Foreword ..................................................................................III Young Minds .................................................................................. 104 Gender Warrior ............................................................................. 108 Introduction ..............................................................................V 4 O’ Clock ...................................................................................... -

Country of Origin Information Report on South and Central Somalia

Country of Origin Information Report on South and Central Somalia Date March 2019 Page 1 of 62 Country of Origin Information Report on South and Central Somalia | March 2019 Document details The Hague Text by: Directorate for Sub-Saharan Africa Country of Origin Information Cluster (DAF/CAB) Disclaimer: The Dutch version of this report is leading. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands cannot be held accountable for misinterpretations based on the English version of the report. Page 2 of 62 Country of Origin Information Report on South and Central Somalia | March 2019 Table of contents Document details ............................................................................................2 Table of contents .............................................................................................3 Introduction ....................................................................................................5 1 Country information .................................................................................... 7 1.1 Political developments ......................................................................................7 1.1.1 Al-Shabaab ................................................................................................... 10 1.2 The security situation ..................................................................................... 17 1.2.1 General ........................................................................................................ 17 1.2.2 Security situation per member -

31 August 2019

CHILD PROTECTION ASSESSEMENT IN SOMALIA FINAL REPORT UNICEF/SOMALI-CHILD PROTECTION AREA OF RESPONSIBILITY 31 AUGUST 2019 i TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT .................................................................................................................. ii LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... ix LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... ix LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................ xii DEFINITIONS OF TERMS ........................................................................................................ xiv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... xv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... xvi CHAPTER ONE ........................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background and Context........................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................