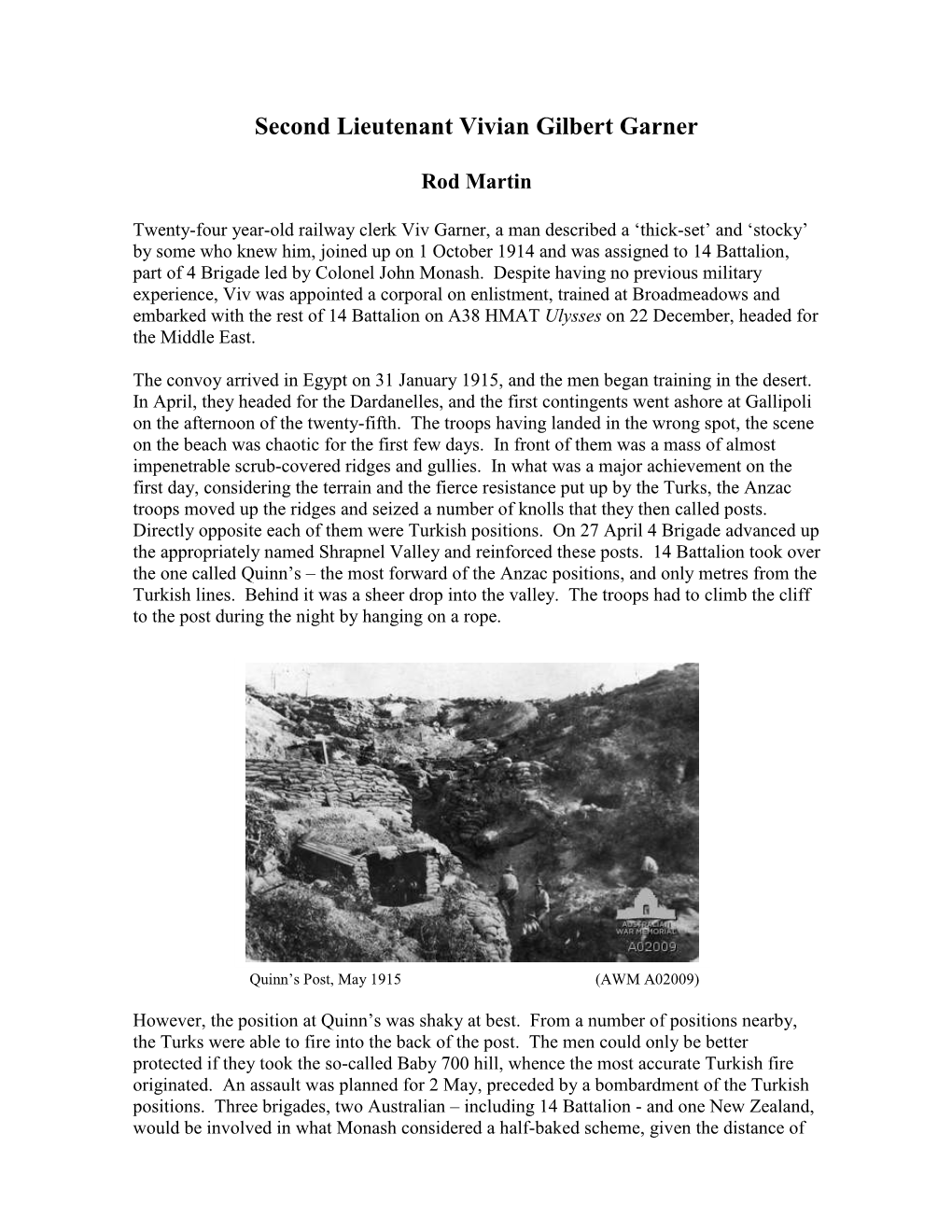

Second Lieutenant Vivian Gilbert Garner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons in Leadership the Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD

Lessons in Leadership The Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD By Rolfe Hartley FIEAust CPEng EngExec FIPENZ Engineers Australia Sydney Division CELM Presentation March 2013 Page 1 Introduction The man that I would like to talk about today was often referred to in his lifetime as ‘the greatest living Australian’. But today he is known to many Australians only as the man on the back of the $100 note. I am going to stick my neck out here and say that John Monash was arguably the greatest ever Australian. Engineer, lawyer, soldier and even pianist of concert standard, Monash was a true leader. As an engineer, he revolutionised construction in Australia by the introduction of reinforced concrete technology. He also revolutionised the generation of electricity. As a soldier, he is considered by many to have been the greatest commander of WWI, whose innovative tactics and careful planning shortened the war and saved thousands of lives. Monash was a complex man; a man from humble beginnings who overcame prejudice and opposition to achieve great things. In many ways, he was an outsider. He had failures, both in battle and in engineering, and he had weaknesses as a human being which almost put paid to his career. I believe that we can learn much about leadership by looking at John Monash and considering both the strengths and weaknesses that contributed to his greatness. Early Days John Monash was born in West Melbourne in 1865, the eldest of three children and only son of Louis and Bertha. His parents were Jews from Krotoshin in Prussia, an area that is in modern day Poland. -

PDF Download Pozieres: the Anzac Story

POZIERES: THE ANZAC STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott Bennett | 416 pages | 01 Jan 2013 | Scribe Publications | 9781921844836 | English | Carlton North, Australia Pozieres: The Anzac Story : Scott Bennett : Howard predicts "a bloody holocaust". Elliott urges him to go back to Field Marshal Haig and inform him that Haking's strategy is flawed. Whether or not Howard was able to do so, remains unclear, but by the morning of the 19th the only result has been a delay in the operation. German defences on the Aubers Ridge and at Fromelles are substantial and continue to cause immense tactical difficulties for the British and Australians. By July , the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division holds more than 7 kilometres of the German front line. Each of the Division's regiments has been allocated a sector, each in turn manned by individual infantry companies. The trenches never run in a completely straight line, but are zig zagged to limit the damage from artillery, machine gun fire and bombing attacks. At their strongest, the German trenches are protected by sandbagged breastworks over two metres high and six metres deep, which makes them resistant to all but direct hits by artillery. This line is further protected by thick bands of barbed wire entanglements. There are two salients in the German line where the opposing forward trenches are at their closest. One is called the Sugarloaf and the other, Wick. Both are heavily fortified and from where machine gunners overlook no man's land and the Allied lines beyond. Along the German line, there are about 75 solid concrete shelters. -

Jack Castle-Burns

THE Simpson PRIZE A COMPETITION FOR YEAR 9 AND 10 STUDENTS 2013 Winner Australian Capital Territory Jack Castle-Burns Marist College Canberra What does an investigation of primary sources reveal about the Gallipoli experience and to what extent does this explain the origins of the ANZAC Legend? Jack Castle-Burns Maris College Canberra 13 Battles can be defining points in a nation’s history. The Battle of Gallipoli is no exception to this and is celebrated as a fundamental aspect of Australia’s foundation. The ANZAC Legend is often considered to have originated at Gallipoli where soldiers acted valiantly, never gave up and supported their mates. Many of these aspects that we define as the ANZAC Legend were evinced in World War One and have endured for decades in all of Australia’s conflicts. Sources from Gallipoli, especially those of soldiers, narrate a story of a disorganised and horrific campaign with dramatic and often wasteful loss of life. Sources relate the hardships our ANZACs experienced while official reports and newspapers tell of an overwhelming victory. In all this, through the emotional struggles of soldiers and their amazing feats, the ANZAC Legend was born. Primary sources inform historians that the preparation for the landing of the ANZACs was inadequate and inaccurate. In planning the invasion military staff used a map based on surveys from 18541 that was essentially useless due to its age. From this map further maps were drawn on a smaller scale, which also included intelligence gained through aerial reconnaissance. However, in practice, the maps were highly inaccurate with soldiers reporting numerous geographical faults that led to misdirection upon invasion at Gallipoli2. -

April 2021 Chairman’S Column

THE TIGER The ANZAC Commemorative Medalion, awarded in 1967 to surviving members of the Australian forces who served on the Gallipoli Peninsula or their next of kin THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 113 – APRIL 2021 CHAIRMAN’S COLUMN Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to The Tiger. It would be improper for me to begin this month’s column without first acknowledging those readers who contacted me to offer their condolences on my recent bereavement. Your cards and messages were very much appreciated and I hope to be able to thank you all in person once circumstances permit. Another recent passing, reported via social media, was that of military writer and historian Lyn Macdonald, whose Great War books, based on eyewitness accounts of Great War veterans, may be familiar to many of our readers. Over the twenty years between 1978 and 1998, Lyn completed a series of seven volumes, the first of which, They Called It Passchendaele, was one of my earliest purchases when I began to seriously study the Great War. I suspect it will not surprise those of you who know me well to learn that all her other works also adorn my bookshelves! The recent announcement in early March of a proposed memorial to honour Indian Great War pilot Hardit Singh Malik (shown right) will doubtless be of interest to our “aviation buffs”. Malik was the first Indian ever to fly for the Royal Flying Corps, having previously served as an Ambulance driver with the French Red Cross. A graduate of Balliol College, Oxford, it was the intervention of his tutor that finally obtained Malik a cadetship in the R.F.C. -

Print This Page

RAAF Radschool Association Magazine – Vol 39 Page 12 Iroquois A2-1022 On Friday the 16th March, 2012, an Iroquois aircraft with RAAF serial number A2-1022, was ceremoniously dedicated at the Caloundra (Qld) RSL. Miraculously, it was the only fine day that the Sunshine Coast had had for weeks and it hasn't stopped raining since. It was suggested that the reason for this was because God was a 9Sqn Framie in a previous life. A2-1022 was one of the early B model Iroquois aircraft purchased and flown by the RAAF and in itself, was not all that special. The RAAF bought the B Models in 3 batches, the 300 series were delivered in 1962, the 700 series in 1963 and the 1000 series were delivered in 1964. A2- 1022 was of the third series and was just an Iroquois helicopter, an airframe with an engine, rotor, seats etc, much the same as all the other sixteen thousand or so that were built by the Bell helicopter company all those years ago – it was nothing out of the ordinary. So why did so many people give up their Friday to come and stand around in the hot sun for an hour or more just to see this one?? The reason they did was because there is quite a story associated with this particular aircraft and as is usually the case, the story is more about the people who flew it, flew in it and who fixed it – not about the aircraft itself. It belonged to 9 Squadron which arrived in Vietnam, in a roundabout route, in June 1966 with 8 of this type of aircraft and was given the task of providing tactical air transport support for the Australian Task Force. -

Historical Officers Report July 2015 Events of the Great War As Reported

Historical Officers Report July 2015 Events of the Great War as reported in the Camden News Cables from the European War 1st July 1915 Athens report that the Allied fleets violently bombarded Gallipoli on Wednesday; at the end of the cannonade immense flames were seen to shoot up in different parts of the town. It is believed that the munitions lying in the dock were set afire, besides several military warehouses. Mr. Ashmead Bartlett, writing from the Dardanelles says that Von Sanders who threatened to drive the British into the sea received another hiding on May 18th from the Australians and New Zealanders. Turkish losses, Mr. Bartlett says, amounted to at least 8000 as compared with 500 Colonials, killed and wounded. Ellis Ashmead Bartlett Except for a violent artillery duel north of Arras operations on the western fronts are quiet. A party 330 Australian and New Zealanders wounded has been landed at Plymouth all except one were able to walk. 8th July 1915 General Hamilton reports that fierce Turkish attacks have been made upon the Allies Forces in Gallipoli and an attempt made to drive the Australians into the sea. The attacks were repulsed inflicting tremendous losses. Sir Ian Hamilton state that reports from the Australian and New Zealander Corps shows the attack was commenced with very heavy fire at midnight on the 28th June and lasted to 1.30 a.m. To this attack the Australians and New Zealanders only replied with a series of Cheers 15th July 1915 News from the Dardanelles reported that extremely intense artillery fire was opened against the French first line. -

The London Gazette of FRIDAY, the 23Rd of JULY, 1915

29240. 7279 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of FRIDAY, the 23rd of JULY, 1915. The Gazette is registered at t/ie General Post Office for transmission by Inland Post as a newspaper. The postage rate to places within the United Kingdom is one halfpenny for each copy. For places abroad the rate is a halfpenny for every 2 ounces, except in the case of Canada, to which the Canadian Magazine Postage rate applies. ° SATURDAY, 24 JULY, 1915. War Office, of Krithia, Dardanelles. When a detach- 24:th July, 1915. ment of a battalion on his left, which had lost all its officers, was rapidly retiring before- His Majesty the KING has been graciously a heavy Turkish attack, Second Lieutenant pleased to award the Victoria Cross to the Moor, immediately grasping the danger to undermentioned Officers and Non-commis- the remainder of the line, dashed back some- sioned Officers:— 200 yards, stemmed the retirement, led back Captain Eustace Jotham, 51st Sikhs (Fron- the men, and recaptured the lost trench. tier Force). This young officer, who only joined the- For most conspicuous bravery on 7th Army in October, 1914, by his personal January, 1915, at Spina Khaisora (Tochi bravery and presence of mind, saved a dan- Valley). gerous situation. During operations against the Khostwal tribesmen, Captain Jotham, who was com- manding a party of about a dozen of the No. 465 Lance-Corporal Albert Jacka, 14th North Waziristan Militia, was attacked in a Battalion, Australian Imperial Forces. nullah and almost surrounded by an over- whelming force of some 1,500 tribesmen. For most conspicuous bravery on the night He gave the order to retire, and could have of the 19th-20th May, 1915, at " Courtney's. -

Sasha Massey St Patrick's College

THE Simpson PRIZE A COMPETITION FOR YEAR 9 AND 10 STUDENTS 2017 Winner Tasmania Sasha Massey St Patrick's College "The experience of Australian soldiers on the Western Front in 1916 has been largely overlooked in accounts of the First World War." To what extent would you argue that battles such as Fromelles and Pozières should feature more prominently in accounts of the First World War? It has been engraved into our national identity to commemorate the sacrifice of those who have participated in conflict, but perhaps one of the greatest tragedies of how we remember World War 1 is that details of battles on the Western Front have eluded the Australian public. Gallipoli, ANZAC Cove and Lone Pine usually dominate the national conversation on ANZAC Day, but the Western Front deserves greater recognition. The loss of a loved one on the Western Front is not an uncommon story, with approximately 45,000 Australian’s being killed.1 The Australian soldiers faced a monumental struggle in France and Belgium, with an immense death toll and unspeakable conditions. It is not only the conditions that were faced that justify the need for a more prominent commemoration of the battles on the Western Front, but they are also very important in the formation of the ANZAC spirit. When Australians think of the ANZACs, we think of tremendous courage, mateship and heroism, qualities that were displayed in abundance on the Western Front, especially at Fromelles and Pozieres. By preserving the legacy of those who served at Pozieres and Fromelles we can remember the lessons they taught us and strive for the qualities they demonstrated. -

TREASURES GALLERY LARGE PRINT LABELS Please Return After Use MARCH 2014 MAP

TREASURES GALLERY LARGE PRINT LABELS Please return after use MARCH 2014 MAP MAP TREASURES/ NLA-Z TERRA AUSTRALIS TO AUSTRALIA entry REALIA exit REALIA RobeRt Brettell bate, MatheMatical, optical & Philosophical Instruments, Wholesale, Retail & for Exportation, London Surveying instruments used by Sir Thomas Mitchell during his three expeditions 1831–1846 brass, bronze, iron, glass and cedar Maps ColleCtion DonateD by the DesCenDants of sir thoMas MitChell Sir Thomas Mitchell’s sextant Thomas Livingstone Mitchell (1792–1855) was appointed Surveyor-General for New South Wales in 1828. At the time, the Survey Department’s inadequate equipment and failure to coordinate small surveys were delaying the expansion of settlement. Mitchell argued for importing better equipment and conducting a general survey of the colony. He also oversaw the creation of the first road network. Mitchell’s explorations led to the discovery of rich pastoral land, dubbed ‘Australia Felix’ (Latin for ‘Happy Australia’), in central and west Victoria. eMi austRalia, Sydney, and eMi GRoup, London Torch of the xVI Olympiad Melbourne 1956 diecast aluminium alloy and silver piCtures ColleCtion reCent aCquisition 1956 Olympic torch This is one of 110 torches used in the torch relay, which began in Cairns, Queensland, on 9 November. Athlete Ron Clarke lit the cauldron to open the Games of the XVI Olympiad in Melbourne on 22 November 1956. Shared between 3118 torchbearers, a cylindrical fuel canister of naphthalene and hexamine was clipped to the base of the bowl and each torch was reused up to 25 times. Two mobile workshops accompanied the relay to keep the torches burning. bluesky (design consultant) G.a. -

War-Related Heritage in Victoria

War-related heritage in Victoria The results of a heritage survey documenting the places and objects relating to Victorians’ experiences of war including war memorials, avenues of honour, commemorative places and buildings, honour rolls, memorabilia, objects and other heritage August 2011 This report is based on a veterans heritage survey For more information contact the Department of prepared by Dr David Rowe of Authentic Heritage Planning and Community Development on Services. It was edited, revised and prepared for (03) 9935 3041 or at www.veterans.vic.gov.au publication by Dr Marina Larsson, Veterans Unit, Disclaimer Department of Planning and Community Development, and Dr Janet Butler. This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee Dr David Rowe has a Bachelor of Arts (Architecture), that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is Bachelor of Architecture and a PhD (Architecture). He wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and is the Heritage Advisor to the City of Greater Geelong therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other and Golden Plains Shire. David is also the Director of consequence which may arise from you relying on any Authentic Heritage Service Pty Ltd, a private heritage information in this publication. consultancy company. Over the past 17 years, David has prepared a large range of local government Copyright material heritage studies, conservation management plans and Where images are still within their copyright period, other heritage assessments on thousands of places all reasonable efforts have been made in order to across Victoria and has authored a number of heritage determine and acknowledge the identity of holders of publications. -

The Gallipoli Vcs, This Company of the Exhibition Will Contain the Memorial’S Complete Collection of Victoria Crosses from the Gallipoli Campaign

ICONS n March 20 the Australian War Memorial is launching a landmark travelling exhi- bition. For the first time ever, nine Victoria Crosses from its Ocollection will tour the country. Titled This company of brave men: the Gallipoli VCs, THIS COMPANY OF the exhibition will contain the Memorial’s complete collection of Victoria Crosses from the Gallipoli campaign. The tour is being held to mark the 95th anniversary of the Gallipoli campaign, and is made pos- sible through the generous sponsorship BRAVE MEN: of Mr Kerry Stokes AC and Seven Network Limited. The Victoria Cross is the highest form of recognition that can be bestowed on THE GALLIPOLI an Australian soldier for remarkable and unselfish courage in the service of others. It is a rare award, given when the nation Portrait of Captain Hugo Vivien Hope Throssell VC of the is at war, facing peril or a great test of na- 10th Australian Light Horse Regiment Australian War Memorial Director Steve Gower and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs Alan Griffin, tional commitment. All ranks of the serv- showing some of the Australian War Memorial’s collection of medals which include the Victoria Cross ices are eligible for the Victoria Cross. It is democratic in its nature and its distribu- tion reflects great integrity. The award has its origins in the mid-nineteenth century, when Queen Victoria instituted the medal Post, Gallipoli, on May 19, 1915. On that day in the early hours of the 29th. Throssell and as a special tribute to recognise acts of out- he and four other men were holding a por- his men became involved in a fierce bomb standing courage. -

The Australian War Memorial Battlefield Guide Free

FREE ANZACS ON THE WESTERN FRONT: THE AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL BATTLEFIELD GUIDE PDF Peter Pedersen,Chris Roberts | 600 pages | 03 Oct 2012 | John Wiley & Sons Australia Ltd | 9781742169811 | English | Milton, QLD, Australia Anzacs on the Western Front: The Australian War Memorial Battlefield Guide by Peter Pedersen Collection type Library Author Pedersen, P. Peter Andreas; Roberts, Chris. Pagination xxiv, p. Includes bibliographical references and index. Meticulously researched and written by the Head of Research at the Australian War Memorial, Dr Peter Pedersen, this landmark publication guides readers chronologically through the battles in which Australians and New Zealanders fought on the Western Front from Lavishly illustrated in vibrant colour, with fascinating images from the Australian War Memorial arch ive as well as new panoramic location shots to provide an in situ perspective for the reader, each chapter covers the important tactical milestones passed along the way and explains how Anzacs on the Western Front: The Australian War Memorial Battlefield Guide Australian Imperial Force and the New Zealand Expeditionary Force evolved to meet the war's changing demands. Place made Milton, Qld. Shelf Items. Share this page. Related information. Subjects Australia. Battlefields - Europe - Guidebooks. World War, - Battlefields - Europe - Guidebooks. World War, - Participation, Australian. World War, - Participation, New Zealand. Explore the Collection. Come and see why. Find out more. Donate today. Places of Pride Places of Pride, the National Register of War Memorials, is a new initiative designed to record the locations and photographs of every publicly accessible memorial across Australia. Includes index. With rare photographs and documents from the Australian WarMemorial archive and extensive travel information, this is the mostcomprehensive guide to the battlefields of the Western Front on themarket.