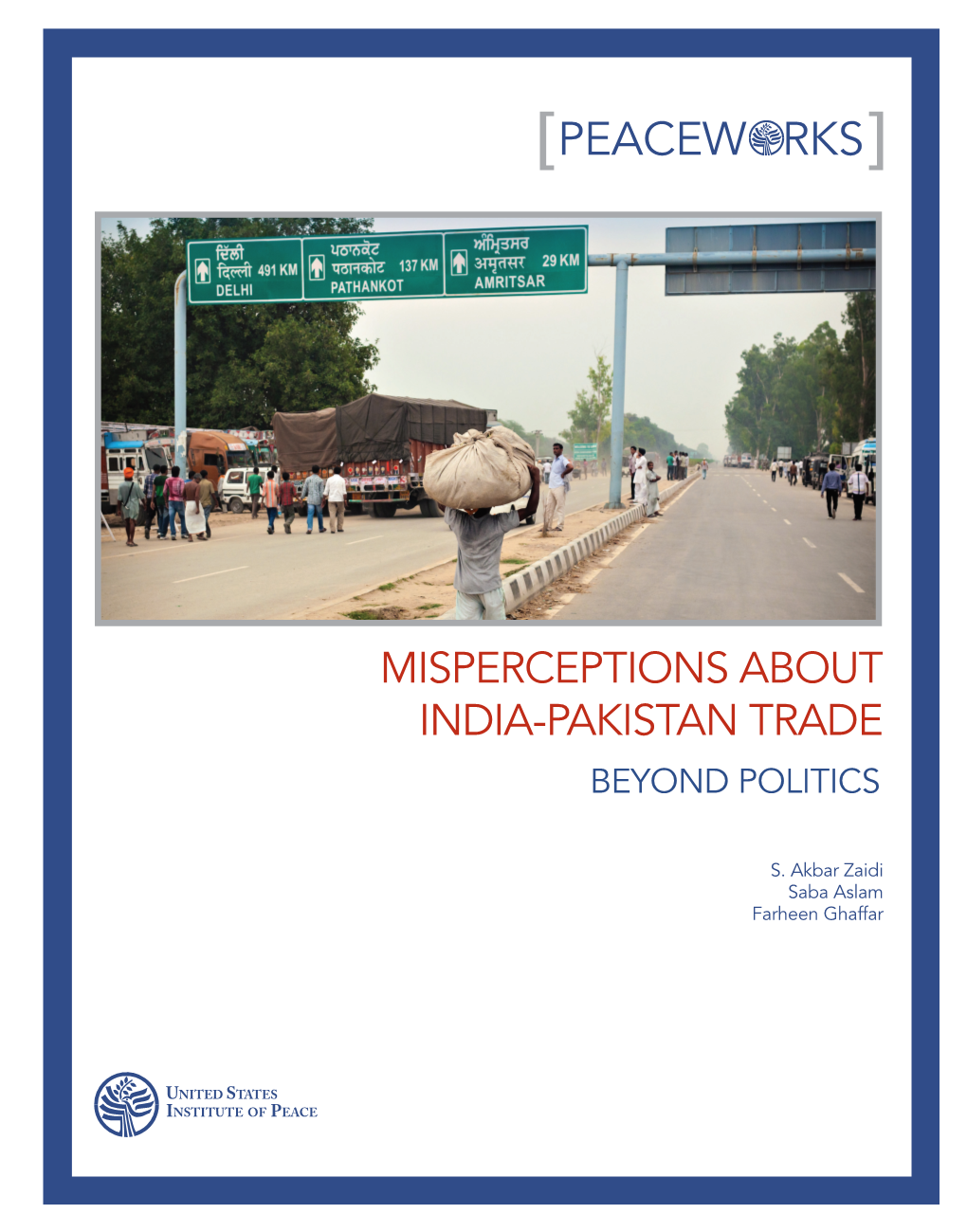

USIP: Misperceptions About India-Pakistan Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning Mobile Growth Into Broadband Success: Case Study of Pakistan

Turning mobile growth into broadband success: Case Study of Pakistan Syed Ismail Shah, PhD Chairman, Pakistan Telecommunication Authority E-mail: [email protected] Evolution of Cellular Mobile Communication in Pakistan 2 Evolution of Cellular Mobile Communication in Pakistan 3 • Total Spectrum offered was 2 lots with the following configuration: • Total Spectrum 2X13.6MHz • 2X4.8MHz in 900MHz band and 2X 8.8MHz in 1800MHz band • Existing Operators were to pay the same amount upon expiry of license with spectrum normalization except for Instaphone, who were only offered 2x7.38MHz in the 850 MHz band Total Teledensity (Millions) 4 GSM Coverage Data revenues Data Revenues in the Telecoms Quarterly Shares of Data Revenue in Total Cellular Reve Sector 25.0 100 25.00% 19.30% 90 20.0 80 20.00% 16.40% 24.1 70 15.80% 15.0 23.5 60 13.70% 15.00% 12.40% 21.4 50 90 10.0 16.7 40 10.00% Percentage 72.2 15.0 30 64.7 50.3 5.0 20 42.6 5.00% 10 - 0 0.00% Oct- Jan - Apr - Jul - Sep Oct- 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 Dec-13 Mar-14 Jun 14 14 Dec-14 Rs. Billion Percentage • Revenue from data is now more than double what it was five years ago • For cellular mobile segment, share of data revenue has crossed 24% LDN Network Diagram Fiber Backbone LDN-T has developed its backbone Network covering 78 cities. Ring, Enhanced Ring, Mesh & Spur network topologies have been used to create backbone. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos -

Asia's Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall of Asia Author: Sonia P.G. Gujral 3 June 2009 Unfortunately another conflict is gong on in Pakistan….. …we are full speed with the operation and a lot of information is flowing through the website: reports, frequency information, meeting minutes and….a nice “mission diary”. Every two days Dane, deployed on the ground, is writing about his time in Pakistan and this gives us the opportunity to feel the atmosphere, understand the difficulties and live some of the experiences he and the other colleagues are having during the emergency operation. Days ago one of his “little stories” made me feel particularly involved in the situation….Dane was in the Pakistani side of Punjab, the “Land of the Five Rivers”, a mile stone in the history of the British Indian Empire....and where half of my blood comes from! The Indian state of Punjab was created in 1947, when the historical partition of India from Pakistan divided the previous province of Raj Punjab between the two countries. Indian Punjab was, and still is, mainly populated by Sikhs ….and this is where I pop into the story! ….I am “half Sikh” (PS: Sikh = do you know Sandokan?) Back to the mission diary, the post was saying: “….after that delicious lunch in Lahore, I hit the road again. I visited WFP border logistics office at Wagah border point and was honoured with first row seat in ''flag lowering'' show!” The Wagah border, often called the “Berlin wall of Asia’’, is a ceremonial border on India–Pakistan border, where each evening there is a ceremony called “Lowering of the Flags”. -

The Kartarpur Pilgrimage Corridor: Negotiating the ‘Line of Mutual Hatred’

International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Volume 9 Issue 2 Sacred Journeys 7: Pilgrimage and Article 5 Beyond: Going Places, Far and Away 2021 The Kartarpur Pilgrimage Corridor: Negotiating the ‘Line of Mutual Hatred’ Anna V. Bochkovskaya Lomonosov Moscow State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Bochkovskaya, Anna V. (2021) "The Kartarpur Pilgrimage Corridor: Negotiating the ‘Line of Mutual Hatred’," International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage: Vol. 9: Iss. 2, Article 5. doi:https://doi.org/10.21427/2qad-kw05 Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol9/iss2/5 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. © International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage ISSN : 2009-7379 Available at: http://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/ Volume 9(ii) 2021 The Kartarpur Pilgrimage Corridor: Negotiating the ‘Line of Mutual Hatred’ Anna Bochkovskaya Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia [email protected] After the partition of British India in 1947, many pilgrimage sites important for the Sikhs – followers of a medieval poet-mystic and philosopher Guru Nanak (1469-1539) – turned out to be at different sides of the Indian-Pakistani border. The towns of Nankana Sahib and Kartarpur (Guru Nanak’s birthplace, and residence for the last 18 years of his life, respectively) remained within Pakistani territory. Gurdwaras located there represent utmost pilgrimage destinations, the Sikhs’ ‘Mecca and Medina’. Owing to Indian-Pakistani relations that have deteriorated throughout seven decades, pilgrimage to Kartarpur has been extremely difficult for India’s citizens. -

A New India-Pakistan Ceasefire: Will It Hold?

12 16 March 2021 A New India-Pakistan Ceasefire: Will It Hold? Tridivesh Singh Maini FDI Visiting Fellow Key Points The Joint Statement by the Directors-General of Military Operations (DGMO) of India and Pakistan calling for a ceasefire is being attributed to various reasons, both internal and external. It comes days after the decision of both India and China to disengage. Days before the statement by the DGMOs , there were some indicators of a thaw, if one were to go by the statements of Pakistan Army Chief Qamar Javed Bajwa, and even Prime Minister Imran Khan during his visit to Sri Lanka. For both countries, the best way ahead would be to get results from low-hanging fruit like bilateral trade. It will be important to see if bilateral tensions can be reduced and whether the South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC), which has been in limbo for nearly five years, can be revived. Summary The ceasefire on 24 February that was agreed upon by India and Pakistan is important for a number of reasons. First, it comes a year-and-a-half after the already strained ties between India and Pakistan had deteriorated even further after New Delhi revoked Article 370 of the Indian Constitution in Kashmir. Second, it comes days after India and China decided to resolve tensions after a period of almost nine months by withdrawing their troops from the North and South Banks of Pangong Lake at the Line of Actual Control. Third, this ceasefire was declared a little over a month after US President Joe Biden took office as President of the US. -

India-Pakistan Relations India Desires Peaceful, Friendly and Cooperative Relations with Pakistan, Which Require an Environment

India-Pakistan Relations India desires peaceful, friendly and cooperative relations with Pakistan, which require an environment free from violence and terrorism. In April 2010, during the meeting between Prime Minister and then Pak PM Gilani on the margins of the SAARC Summit (Thimpu) PM spoke about India's willingness to resolve all outstanding issues through bilateral dialogue. Follow up meetings were held by the two Foreign Ministers (Islamabad, July 2010), and the two Foreign Secretaries (Thimphu, February 2011). During the latter meeting it was formally agreed to resume dialogue on all issues: (i) Counter-terrorism (including progress on Mumbai trial) and Humanitarian issues at Home Secretary level; (ii) Peace & Security, including CBMs, (iii) Jammu & Kashmir, and (iv) promotion of friendly exchanges at the level of Foreign Secretaries; (v) Siachen at Defence Secretary-level; (vi) Economic issues at Commerce Secretary level; (vii) Tulbul Navigation Project/ Wullar Barrage at Water Resources Secretary-level; and (viii) Sir Creek (at the level of Surveyors General/ Additional Secretary). Since then several efforts have been made by the two countries to enhance people-to-people contacts. Cross-LoC travel and trade across J&K, initiated in 2005 and 2008 respectively, is an important step in this direction. Further, India and Pakistan signed a new visa agreement in September 2012 during the visit of then External Affairs Minister to Pakistan. This agreement has led to liberalization of bilateral visa regime. Two rounds of the resumed dialogue have been completed; the third round began in September 2012, when the Commerce Secretaries met in Islamabad. Talks on conventional and non-conventional CBMs were held in the third round in December 2012 in New Delhi. -

Punjab Punjab Trade – Case for Opening up of Wagha Attari Route

Punjab Punjab Trade – Case for Opening Up of Wagha Attari Route By Huma Fakhar Managing Partner MAP Services Group www.mapservicesgroup.com Background • Before partition the flow of economic progress of the region was towards central Punjab represented by two prominent cities, Lahore as political capital of Punjab and cultural centre of north India and Amritsar as centre of trade and commerce. • East Punjab and West Punjab were allocated respectively to India and Pakistan in 1947. • There was a tremendous trade route from Sialkot right upto Ambala • Punjab strip has the potential to be the food bowl for the two countries including a strong base for industrial progress. • The line of partition changed the direction of economic progress from the region centric towards outside big cities of the two countries as the two central cities of the region (Lahore and Amritsar) had been converted into border cities. However, things did seem to be amiable and pragmatic for a while • In 1948-49 Pakistan’s exports to India accounted for 56% of its total exports while 32% of Pakistan’s imports came from India . The two countries were trading normally during this turbulent period. India was Pakistan’s largest trading partner and this continued to be the case till 1955-56. • Between 1948 and 1965, Pakistan and India used a number of land routes for bilateral trade. These included eight (8) Customs stations in Punjab province at Wagha, Takia Ghawindi, Khem Karan, Ganda Singhwala, Mughalpura Railway Station, Lahore Railway Station, Haripur Bund on River Chenab, and the Macleod Ganj Road Railway Station. -

Final Report

USAID Trade Project Final Report USAID Trade Project USAID/Pakistan Office of Economic Growth & Agriculture Contract Number: Task Order EEM-I-03-07-00005 September 2014 Disclaimer: This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Deloitte Consulting LLP. \ Trade Project Table of Contents Table of Acronyms & Initialisms .................................................................................................. 1 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Project Background ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Select Accomplishments .................................................................................................................... 6 2. Improved Pakistan Trade Environment (Component 1) ....................................................... 11 2.1 Support to the Ministry of Commerce ............................................................................................... 11 2.2 Strengthening the Human and Institutional Capacity of the National Tariff Commission ................. 19 2.3 Anti-Dumping Appellate Tribunal (ADAT) ......................................................................................... 24 2.4 Government of Pakistan Compliance with the Revised Kyoto Convention -

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: LAHORE, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE for RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 17Th, 2014

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: LAHORE, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE FOR RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 17th, 2014 Rains/Floods 2014: Lahore District Profile September 2014 iMMAP-USAID District at a Glance Administrative DivisionR ajanpur - Reference Map Police Stations (http://www.lahorepolice.gov.pk/) Attribute Value District/tehsil Knungo Patwar Number of Mouzas Sr. No. Police Station Phone No. Population (2014 est) 9,396,398 Circles/ Circles/ 1 SP Iqbal Town Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99230660 Male 4,949,706 (53%) Supervisory Tapas Total Rural Urban Partly Forest Un- 2 SP Iqbal Town Div. (Inv. Wing) 0092 42 99233331 Tapas urban populated Female 4,446,692 (47%) 3 Iqbal Town 0092 42 37801375 DISTRICT 22 213 360 211 92 40 17 4 SP Saddar Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99262023-4 Rural 1,650,134 (18%) LAHORE CITY 10 76 115 51 40 15 9 Urban 7,746,264 (82%) LAHORE 5 SP Saddar Div. (Inv. Wing) 0092 42 99262028-7 12 137 245 160 52 25 8 Tehsils 2 CANTT 6 Johar Town 0092 42 99231472 Towns & Cantonment 9 & 1 Source: Punjab Mouza Statistics 2008 7 SP Cantt. Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99220615/ 99221126 UC 165 8 SP Cantt. Div. (Inv. Wing) 0092-52-3553613 Road Network Infrastructure: District Roads: 1,244.41 (km), NHWs: 48.43 (km), Prov. Highways: Revenue Villages/Mouza 360 9 SP Model Town Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99263421-2 113.6 (km) R&B Sector: 245.31 (km), Farm to Market: 343.47 (km), District Council Roads: 493.6 (km) 10 SP Model Town (Inv. -

Geotechnical Statistical Evaluation of Lahore Site Data and Deep Excavation Design

Portland State University PDXScholar Civil and Environmental Engineering Master's Project Reports Civil and Environmental Engineering 2015 Geotechnical Statistical Evaluation of Lahore Site Data and Deep Excavation Design Aiza Malik Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cengin_gradprojects Part of the Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Malik, Aiza, "Geotechnical Statistical Evaluation of Lahore Site Data and Deep Excavation Design" (2015). Civil and Environmental Engineering Master's Project Reports. 13. https://doi.org/10.15760/CEEMP.17 This Project is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Civil and Environmental Engineering Master's Project Reports by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. CE 501 GEOTECHNICAL STATISTICAL EVALUATION OF LAHORE SITE DATA AND DEEP EXCAVATION DESIGN Submitted By: Aiza Malik A research project report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING Project Advisor: Dr. Trevor Smith DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY USA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Trevor Smith for his continuing support and help throughout the project. I would also like to thank the following companies and institutes for providing site data for Lahore, Pakistan. 1. Geo Associates and Consultants, Lahore 2. Building Standards, Lahore 3. National Engineering Services Pakistan (NESPAK), Lahore 4. University of Engineering and Technology Lahore (UET), Lahore ABSTRACT Geotechnical characterization for foundation design is critical during preliminary planning, designing and feasibility studies of various engineering projects. -

Agreementbetweenthe Governmentof the Republicof India And

AGREEMENTBETWEENTHE GOVERNMENTOFTHE REPUBLICOF INDIA ANDTHE GOVERNMENTOFTHE ISLAMIC REPUBLICOF PAKISTANFORTHE REGULATIONOF BUS SERVICEBETWEENAMRITSAR(INDIA) AND LAHORE(PAKISTAN) The Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, (hereinafter referred to individually as a "Party" and collectively as the "Parties',), Having agreed to explore possibilities of promotion and expansion of vehicular traffic between the two countries on the basis of mutual advantage and reciprocity, Desiring to strengthen interaction between the people of the two countries on the basis of common interests, by operating a passenger bus service between Amritsar and Lahore, Haveagreed as follows: ARTICLE- I DEFINmONS Unlessotherwise provided in the text, the term- a) "Act" means the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 of India and the Provincial Motor Vehicles Ordinance (W.P.Ord. XIX of 1965) of Pakistan; "Authorization Fee" means the fee to be paid by the permit holder of one country to the other country for obtaining authorization; c) "Bus crew" means driver, conductor and liaison officer; d) "Certificate of fitness" means a certificate issued by the competent authorities of one of the two countries, testifying to the fitness of the vehicle to ply on the road; e) "Competent authority" means in relation to- i) "Permits", an authority competent to issue such a permit authorized by the Party concerned; ii) "Driving license" an authority competent to issue a driving license authorized by the Party concerned; iii) "Conductor's license", -

Gujarat, Rajasthan and Punjab: E Need for a Border States Group

Policy Report No. 6 Gujarat, Rajasthan and Punjab: e Need for a Border States Group TRIDIVESHTRIDIVESH SINGH MAINI MAINI © The Hindu Centre for Politics & Public Policy, 2014 The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy is an independent platform for an exploration of ideas and public policies. Our goal is to increase understanding of the various aspects of the challenges today. As a public policy resource, our aim is to help the public increase its awareness of its political, social and moral choices. The Hindu Centre believes that informed citizens can exercise their democratic rights better. In accordance with this mission, The Hindu Centre publishes policy and issue briefs drawing upon the research of its scholars and staff that are intended to explain and highlight issues and themes that are the subject of public debate. These are intended to aid the public in making informed judgments on issues of public importance. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher. GUJARAT, RAJASTHAN & PUNJAB The Need for a Border States Group TRIDIVESH SINGH MAINI POLICY REPORT NO.6 THE NEED FOR A BORDER STATES GROUP ABSTRACT NDIA-PAKISTAN ties over the past decade have been a mixed bag. There have been Isignificant tensions, especially in the aftermath of the 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks in 2008, and the beheading of Indian soldiers across the Line of Control (LOC) in August 2013. Amid these tensions, however, there have been noteworthy achievements in the realm of bilateral trade, where trade through the Wagah-Attari land route has gone up nearly four-fold from $664 million (2004) to approximately $2.6 billion (2012-2013) (Source: Ministry of Commerce).