The Sikh Community in Indian Punjab: Some Socio-Economic Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quality of Water in Chandigarh (Panchkula and Mohali Region)

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 7, Issue 4, July-August 2016, pp. 539–541 Article ID: IJCIET_07_04_050 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJCIET?Volume=7&Issue=4 ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication QUALITY OF WATER IN CHANDIGARH (PANCHKULA AND MOHALI REGION) Raman deep Singh Bali Department of Civil Engineering, Chandigarh University, Gharuan, Mohali, India Puneet Sharma Assistant professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Chandigarh University, Gharuan, Mohali, India ABSTRACT As we know among all the natural resources water is one of the most important resource which cannot be neglected. So it is essential to know the water method for sources time to time for the calm change. About 97% of the earth’s surface is covered by water and about 60-65% of water is present in the animal and plant bodies. 2.4% are present on glaciers and polar ice caps. Heavy metals can be found in industrial waste water are deemed undesirable. Exposure of heavy metals in environment degrades the ecosystem which harms the inhabitants. In this paper various parameters have been discussed such as hardness, cadmium, magnesium, chromium, arsenic, iron, calcium, BOD, COD, TDS, pH, conductivity, and temperature for this review study. In this paper nature of ground water, surface water of Chandigarh adjacent areas, for example, Parwano, S.A.S. Nagar (Mohali) have been discussed on the premise of reports accessible online. However, not a lot of studies have been coordinated to check the water way of this area but on the basis of available information, it was found that that the water quality in a portion of the spots is underneath the benchmarks of water quality endorsed by Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS).Appropriate working of Sewerage Treatment Plants (STPs) should be checked also, Industrial waste ought to be appropriately treated before setting off to the catchment ranges. -

20-A Pine Terrace, Howick, Auckland

100 Marathon Club – New Zealand NEWSLETTER FOR MEMBERS – December 2011 1) Two members celebrate their 150th marathon finish Since the last Newsletter, two members have completed their 150th marathon – within a few days of each other. Richard Were ( Auckland YMCA Marathon Club) Richard achieved his 150th marathon finish at the Auckland Marathon on 30th October. Richard completed his first marathon at the Wellington event in January 1985, and his 100th at the Auckland marathon in October 1999. He started running regularly in the spring of 1984 in order to get fit for the next football season. However, he did so much running over the summer that he decided to enter the 1985 Wellington marathon. Over the years Richard has been a member of several Clubs, with his first – a year or so after his first marathon, being the Wellington Scottish Harriers. After moving to Auckland the following year he joined Lynndale for a year, and then subsequently North Shore Bays and then Takapuna for a few years. Since 1999 Richard has been a member of the Auckland YMCA Marathon Club During his marathon career he has had many highlights including – A Personal Best of 2:31:30 at the Buller Gorge Marathon in 1987 . Completing a total of 135 of his 150 marathons in less than 3 hours, with a career average of 2:47:36. Winning a total of 19 marathons – which may well be the largest number by an NZ male. These included – The Great Forest, Waitarere (3 times), Cambridge to Hamilton (3 times), and Whangamata (twice). Overseas he has also achieved firsts in both the Alice Springs (twice) and Muir Woods (California) marathons. -

Turning Mobile Growth Into Broadband Success: Case Study of Pakistan

Turning mobile growth into broadband success: Case Study of Pakistan Syed Ismail Shah, PhD Chairman, Pakistan Telecommunication Authority E-mail: [email protected] Evolution of Cellular Mobile Communication in Pakistan 2 Evolution of Cellular Mobile Communication in Pakistan 3 • Total Spectrum offered was 2 lots with the following configuration: • Total Spectrum 2X13.6MHz • 2X4.8MHz in 900MHz band and 2X 8.8MHz in 1800MHz band • Existing Operators were to pay the same amount upon expiry of license with spectrum normalization except for Instaphone, who were only offered 2x7.38MHz in the 850 MHz band Total Teledensity (Millions) 4 GSM Coverage Data revenues Data Revenues in the Telecoms Quarterly Shares of Data Revenue in Total Cellular Reve Sector 25.0 100 25.00% 19.30% 90 20.0 80 20.00% 16.40% 24.1 70 15.80% 15.0 23.5 60 13.70% 15.00% 12.40% 21.4 50 90 10.0 16.7 40 10.00% Percentage 72.2 15.0 30 64.7 50.3 5.0 20 42.6 5.00% 10 - 0 0.00% Oct- Jan - Apr - Jul - Sep Oct- 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 Dec-13 Mar-14 Jun 14 14 Dec-14 Rs. Billion Percentage • Revenue from data is now more than double what it was five years ago • For cellular mobile segment, share of data revenue has crossed 24% LDN Network Diagram Fiber Backbone LDN-T has developed its backbone Network covering 78 cities. Ring, Enhanced Ring, Mesh & Spur network topologies have been used to create backbone. -

State Profiles of Punjab

State Profile Ground Water Scenario of Punjab Area (Sq.km) 50,362 Rainfall (mm) 780 Total Districts / Blocks 22 Districts Hydrogeology The Punjab State is mainly underlain by Quaternary alluvium of considerable thickness, which abuts against the rocks of Siwalik system towards North-East. The alluvial deposits in general act as a single ground water body except locally as buried channels. Sufficient thickness of saturated permeable granular horizons occurs in the flood plains of rivers which are capable of sustaining heavy duty tubewells. Dynamic Ground Water Resources (2011) Annual Replenishable Ground water Resource 22.53 BCM Net Annual Ground Water Availability 20.32 BCM Annual Ground Water Draft 34.88 BCM Stage of Ground Water Development 172 % Ground Water Development & Management Over Exploited 110 Blocks Critical 4 Blocks Semi- critical 2 Blocks Artificial Recharge to Ground Water (AR) . Area identified for AR: 43340 sq km . Volume of water to be harnessed: 1201 MCM . Volume of water to be harnessed through RTRWH:187 MCM . Feasible AR structures: Recharge shaft – 79839 Check Dams - 85 RTRWH (H) – 300000 RTRWH (G& I) - 75000 Ground Water Quality Problems Contaminants Districts affected (in part) Salinity (EC > 3000µS/cm at 250C) Bhatinda, Ferozepur, Faridkot, Muktsar, Mansa Fluoride (>1.5mg/l) Bathinda, Faridkot, Ferozepur, Mansa, Muktsar and Ropar Arsenic (above 0.05mg/l) Amritsar, Tarantaran, Kapurthala, Ropar, Mansa Iron (>1.0mg/l) Amritsar, Bhatinda, Gurdaspur, Hoshiarpur, Jallandhar, Kapurthala, Ludhiana, Mansa, Nawanshahr, -

Public Relations

Annual Training Camps The Railway TA personnel have to undergo 30 days of mandatory annual training every year to keep themselves physically fit and accustomed with military discipline, arms & ammunition, defence techniques, etc. The annual training camps were duly conducted for the Railway TA personnel of the six Railway TA Regiments during 2011-12. Tourist information centre of Rajasthan at Jaipur Railway Station. Recruitment/Discharge During 2011-12, 480 Railway TA personnel and 1 Officer were inducted into various Railway TA Regiments while 162 Other Ranks (ORs), 12 Junior Commissioned Officers and 1 Officer were discharged/retired from TA Regiments. Ramp connectivity provided at Bilaspur Station. Public Relations Indian Railways’ PR set up is responsible for disseminating information about various policy initiatives, services, concessions, projects, performances and developmental activities undertaken by the Railways. It plays an important role in building both the corporate and social image of IR. Publicity campaigns are launched to educate the rail users on various aspects of railway working including safety and security norms in order to create awareness among the masses. During the last financial year, a special brand building A view of dwelling unit, CLW township. advertisement campaign was undertaken entitled ‘We Deliver’. Special campaigns were also undertaken by IR on revised Tatkal Scheme, need for carrying identity proofs while travelling with Tatkal tickets, information about the various Summer Specials, safety norms at unmanned Railway Level Crossings, hazards of roof top travelling, trespassing of railway tracks, menaces of touts in booking of the tickets, drugging of passengers by strangers on trains and at railway stations, etc. -

Initial Environment Examination IND: Infrastructure Development Investment Program for Tourism

Initial Environment Examination Project Number: 40648-034 January 2017 IND: Infrastructure Development Investment Program for Tourism - Tranche 3 Sub Project : Imperial Highway Heritage C onservation and Visitor Facility Development: (L ot-3) Adaptive Reuse of Aam Khas Bagh and Interpretation Centre/Art and Craft C entre at Maulsari, Fatehgarh Sahib Submitted by Program Management Unit, Punjab Heritage and Tourism Board, Chandigarh This Initial Environment Examination report has been prepared by the Program Management Unit, Punjab Heritage and Tourism Board, Chandigarh for the Asian Development Bank and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. This report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Compliance matrix to the Queries from ADB Package no.: PB/IDIPT/T3-03/12/18 (Lot-3): Imperial Highway Heritage Conservation and Visitor Facility Development: Adaptive Reuse of Aam Khas Bagh and Interpretation Centre/Art and Craft Centre at Maulsari, Fatehgarh Sahib Sl.no Query from ADB Response from PMU 1. We note that there are two components Noted, the para has been revised for better i.e. Aam Khas Bagh and Maulsari (para 3, understanding. -

Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES* (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______ SUBMISSION BY MEMBERS Re: Farmers facing severe distress in Kerala. THE MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI RAJ NATH SINGH) responding to the issue raised by several hon. Members, said: It is not that the farmers have been pushed to the pitiable condition over the past four to five years alone. The miserable condition of the farmers is largely attributed to those who have been in power for long. I, however, want to place on record that our Government has been making every effort to double the farmers' income. We have enhanced the Minimum Support Price and did take a decision to provide an amount of Rs.6000/- to each and every farmer under Kisan Maan Dhan Yojana irrespective of the parcel of land under his possession and have brought it into force. This * Hon. Members may kindly let us know immediately the choice of language (Hindi or English) for obtaining Synopsis of Lok Sabha Debates. initiative has led to increase in farmers' income by 20 to 25 per cent. The incidence of farmers' suicide has come down during the last five years. _____ *MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 1. SHRI JUGAL KISHORE SHARMA laid a statement regarding need to establish Kendriya Vidyalayas in Jammu parliamentary constituency, J&K. 2. DR. SANJAY JAISWAL laid a statement regarding need to set up extension centre of Mahatma Gandhi Central University, Motihari (Bihar) at Bettiah in West Champaran district of the State. 3. SHRI JAGDAMBIKA PAL laid a statement regarding need to include Bhojpuri language in Eighth Schedule to the Constitution. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos -

Central European Journal of International & Security Studies

Vysoká škola veřejné správy a mezinárodních vztahů v Praze Volume 1 / Issue 2 / November 2007 Central European Journal of International & Security Studies Volume 1 Issue 2 November 2007 Contents Editor’s Note . 5 Special Report Daniel Kimmage and Kathleen Ridolfo / Iraqi Insurgent Media: The War of Images and Idea . 7 Research Articles Marketa Geislerova / The Role of Diasporas in Foreign Policy: The Case of Canada . .90 Atsushi Yasutomi and Jan Carmans / Security Sector Reform (SSR) in Post-Confl ict States: Challenges of Local Ownership . 109 Nikola Hynek / Humanitarian Arms Control, Symbiotic Functionalism and the Concept of Middlepowerhood . 132 Denis Madore / The Gratuitous Suicide by the Sons of Pride: On Honour and Wrath in Terrorist Attacks . 156 Shoghig Mikaelian / Israeli Security Doctrine between the Thirst for Exceptionalism and Demands for Normalcy . 177 Comment & Analysis Svenja Stropahl and Niklas Keller / Adoption of Socially Responsible Investment Practices in the Chinese Investment Sector – A Cost-Benefi t Approach . 193 Richard Lappin / Is Peace-Building Common Sense? . 199 Balka Kwasniewski / American Political Power: Hegemony on its Heels? . 201 Notes on Contributors . 207 CEJISS Contact Information. 208 5 Editor’s Note: CE JISS In readying the content of Volume 1 Issue 2 of CEJISS, I was struck by the growing support this journal has received within many scholarly and profes- sional quarters. Building on the success of the fi rst issue, CEJISS has man- aged to extend its readership to the universities and institutions of a number of countries both in the EU and internationally. It is truly a pleasure to watch this project take on a life of its own and provide its readers with cutting-edge analy- sis of current political affairs. -

California's A.Jnjabi- Mexican- Americans

CULTURE HERITAGE Amia&i-Mexicon-Americans California's A.Jnjabi Mexican Americans Ethnic choices made by the descendants of Punjabi pioneers and their Mexican wives by Karen Leonard he end of British colonial rule in India and the birth of two new nations-India and Pakistan-was celebrated in California in T 1947 by immigrant men from India's Punjab province. Their wives and children celebrated with them. With few exceptions, these wives were of Mexican ancestry and their children were variously called "Mexican-Hindus," "half and halves," or sim ply, like their fathers, "Hindus," an American misno mer for people from India. In a photo taken during the 1947 celebrations in the northern California farm town of Yuba City, all the wives of the "Hindus" are of Mexican descent, save two Anglo women and one woman from India. There were celebrations in Yuba City in 1988, too; the Sikh Parade (November 6) and the Old-Timers' Reunion Christmas Dance (November 12). Descend ants of the Punjabi-Mexicans might attend either or The congregation of the Sikh temple in Stockton, California, circa 1950. - -_ -=- _---=..~...;..:..- .. both of these events-the Sikh Parade, because most of the Punjabi pioneers were Sikhs, and the annual ChristmaB dance, because it began as a reunion for descendants of the Punjabi pioneers. Men from In dia's Punjab province came to California chiefly between 1900 and 1917; after that, immigration practices and laws discriminated against Asians and legal entry was all but impossible. Some 85 percent of the men who came during those years were Sikhs, 13 percent were Muslims, and only 2 percent were really Hindus. -

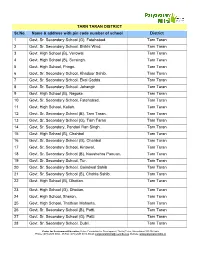

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Download the Punjab Community Profile

Punjabi Community Profile July 2016 Punjab Background The Punjabis are an ethnic group of Indo-Aryan peoples, originating from the Punjab region, found in Pakistan and northern India. Punjab literally means the land of five waters (Persian: panj (“five”) ab (“waters”)). The name of the region was introduced by the Turko-Persian conquerors of India and more formally popularized during the Mughal Empire. Punjab is often referred to as the breadbasket in both Pakistan and India. The coalescence of the various tribes, castes and the inhabitants of the Punjab into a broader common “Punjabi” identity initiated from the onset of the 18th century CE. Prior to that the sense and perception of a common “Punjabi” ethno-cultural identity and community did not exist, even though the majority of the various communities of the Punjab had long shared linguistic, cultural and racial commonalities. Traditionally, Punjabi identity is primarily linguistic, geographical and cultural. Its identity is independent of historical origin or religion, and refers to those who reside in the Punjab region, or associate with its population, and those who consider the Punjabi language their mother tongue. Integration and assimilation are important parts of Punjabi culture, since Punjabi identity is not based solely on tribal connections. More or less all Punjabis share the same cultural background. Historically, the Punjabi people were a heterogeneous group and were subdivided into a number of clans called biradari (literally meaning “brotherhood”) or tribes, with each person bound to a clan. However, Punjabi identity also included those who did not belong to any of the historical tribes.