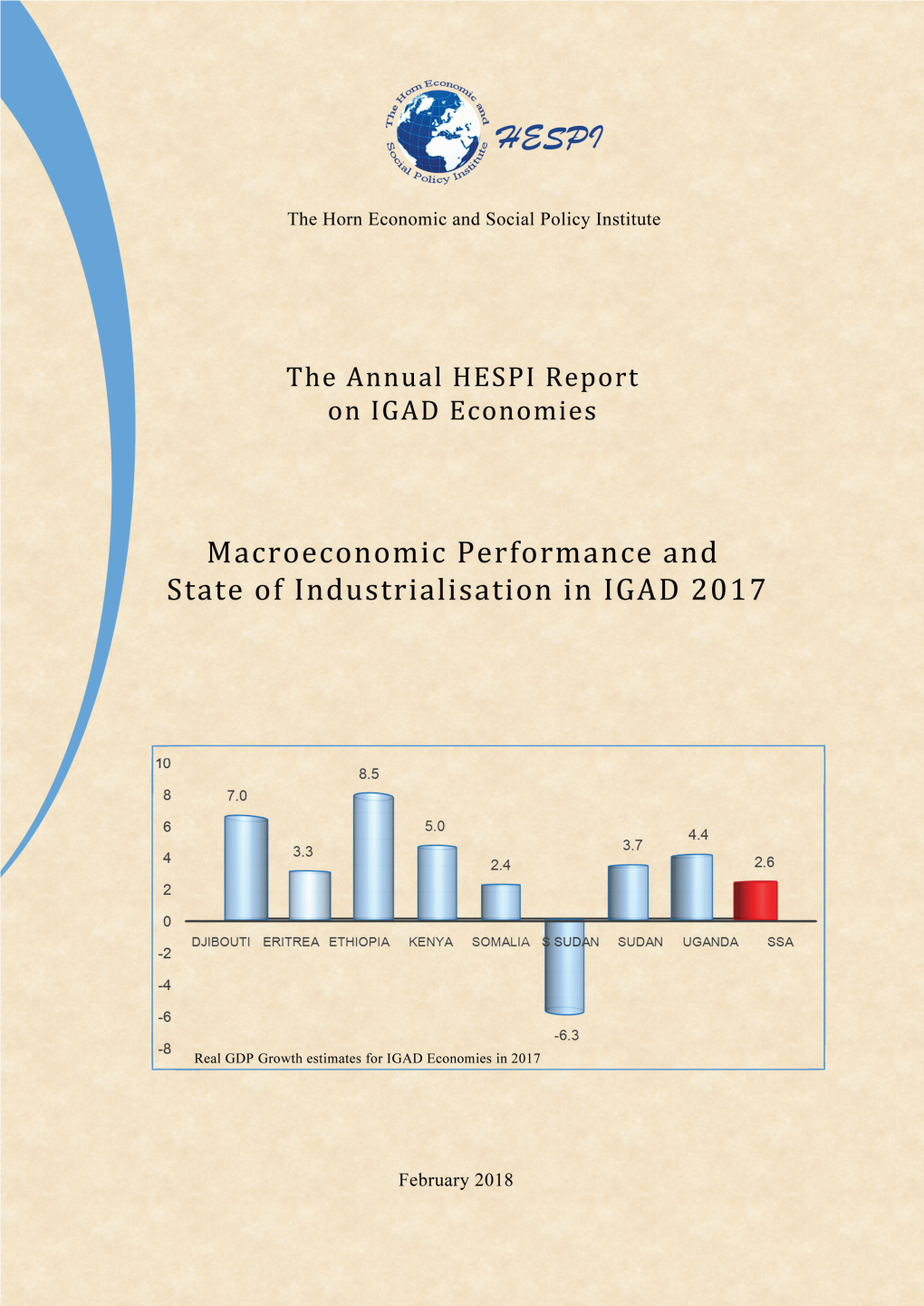

Macroeconomic Performance and Status of Industrialization in IGAD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Thirtieth Ordinary Session 22 - 27 January 2017 Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: 5517 700 Fax: 5517844 Website: www.au.int EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Thirtieth Ordinary Session 22 - 27 January 2017 Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA EX.CL/994(XXX) Final Original: English ANNUAL REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2016 EX.CL/994(XXX)Rev.2 Page i Table of Contents PART A. OVERVIEW (pages 1-13) Introduction; the African Paradox; Agenda 2063; State of African Integration; the African Passport and Free movement of People; 2017 - the Year ahead; Word of Thanks PART B. REPORT OF THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMISSION Commission Highlights of 2016; AUC 3rd Strategic Plan (2013-2017); Meetings of Policy Organs; High-level visits (pages 15-20) Outcome 1. Democracy, Peace, Governance and Human rights (pages 21-34): Introduction; Women’s Empowerment and Participation; Democracy, Human rights and Governance; Promoting free, fair and peaceful elections; African Governance Architecture; the Year of Human Rights; Constitutionalism and Rule of Law; African Public Services and Local Government; AU High Level Council on Local Government; Common African Position on Habitat III; Decolonisation process; Peace and Security; AU Plan of Action on Drug Control and Crime Prevention (2013-2017); Legal support to AU Organs; The Fight against impunity. Outcome 2. Agriculture, natural resource management and food security (pages 35-50): Introduction; Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP); Organic and -

Trends and Spatio-Temporal Variation of Female

Tesema et al. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:719 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08882-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Trends and Spatio-temporal variation of female genital mutilation among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: a Spatio-temporal and multivariate decomposition analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health surveys Getayeneh Antehunegn Tesema1*, Chilot Desta Agegnehu2, Achamyeleh Birhanu Teshale1, Adugnaw Zeleke Alem1, Alemneh Mekuriaw Liyew1, Yigizie Yeshaw3 and Sewnet Adem Kebede1 Abstract Background: Female genital mutilation (FGM) is a serious health problem globally with various health, social and psychological consequences for women. In Ethiopia, the prevalence of female genital mutilation varied across different regions of the country. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the trend and determinants of female genital mutilation among reproductive-age women over time. Methods: A secondary data analysis was done using 2000, 2005, and 2016 Demographic Health Surveys (DHSs) of Ethiopia. A total weighted sample of 36,685 reproductive-age women was included for analysis from these three EDHS Surveys. Logit based multivariate decomposition analysis was employed for identifying factors contributing to the decrease in FGM over time. The Bernoulli model was fitted using spatial scan statistics version 9.6 to identify hotspot areas of FGM, and ArcGIS version 10.6 was applied to explore the spatial distribution FGM across the country. (Continued on next page) * Correspondence: [email protected] 1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia Full list of author information is available at the end of the article © The Author(s). -

Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Associated Factors of Home Delivery in Ethiopia

Spatio-temporal distribution and associated factors of home delivery in Ethiopia. Fruther multilevel and spatial analysis of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys 2005 - 2016 Zemenu Tessema Tadesse ( [email protected] ) University of Gondar https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3878-7956 Sofonyas Abebaw Tiruneh Debre Tabor University Research article Keywords: Home delivery, EDHS, Spatial Distribution, Ethiopia Posted Date: January 3rd, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.16582/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published at BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth on June 3rd, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02986-w. Page 1/30 Abstract Background: Globally, between 2012 -2017 80% of live births occurred at health facilities assisted by skilled health personnel. In Ethiopia, in 2016 only 26% of live births attended by skilled health personal. The aim of this study was to assess the spatial patterns and associated factors of home delivery in Ethiopia using 2005 to 2016 Ethiopian Demgraphic and Health Surveys. Method: A total of 33 482 women who gave live birth in the ve years preceding each survey were included for this study. ArcGIS version 10.7 software was used to visualize spatial distribution of home delivery. The Bernoulli model was applied using Kilduff SaTScan version 9.6 software to identify signicant purely spatial clusters for home delivery in Ethiopia. Multilevel logistic regression model were tted to identify factors associated with home delivery. A p-value < 0.05 was taken to declare statistically signicant predictors. -

South Sudanese Refugees in Uganda and Ethiopia

Theorie und Praxis Wissenschaftliche Reihe zur Entwicklungszusammenarbeit, Humanitären Hilfe und entwicklungspolitischen Anwaltschaftsarbeit Leonore Merck South Sudanese Refugees in Uganda and Ethiopia The effect of refugee-housing on the protection of refugee children against physical and sexual violence World Vision Institut Institut Vision World Nr. 15 Theorie und Praxis Wissenschaftliche Reihe zur Entwicklungszusammenarbeit, humanitären Hilfe und entwicklungspolitischen Anwaltschaftsarbeit, herausgegeben vom World Vision Institut South Sudanese Refugees in Uganda and Ethiopia The effect of refugee-housing on the protection of refugee children against physical and sexual violence Masterarbeit zur Erlangung eines Master of Public Policy von Leonore Merck Hertie School of Governance Berlin Mai 2018 Leonore Merck South Sudanese Refugees in Uganda and Ethiopia The effect of refugee-housing on the protection of refugee children against physical and sexual violence Theorie und Praxis Nr.15 Impressum © World Vision,2018 Herausgeber: World Vision Institut Friedrichsdorf, Deutschland Forschungsleitung: Dr. Caterina Rohde-Abuba HERTIE SCHOOL OF GOVERNANCE BERLIN South Sudanese Refugees in Uganda and Ethiopia The effect of refugee-housing on the protection of refugee children against physical and sexual violence Leonore Merck Master of Public Policy, Class of 2018 Supervisor: Dr. Clara Weinhardt 5/1/2018 In cooperation with World Vision Germany Word Count: 11,955 Acknowledgements I would like to thank World Vision Germany and especially Verena -

Ethiopia Refugee Education Strategy 2015-2018

ETHIOPIA REFUGEE EDUCATION STRATEGY 2015-2018 JUNE 2015 1 | National Refugee Education Strategy 2015-2018 (Ethiopia) Table of Contents ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Background: Contextualization of the UNHCR Global Education Strategy to the Ethiopian Context ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 General Operational Context of the Office of UNHCR Representation in Ethiopia ............. 6 The Organization, Structure and Management of Refugee Education System ..................... 8 Emphases of the Contextualized Refugee Education Strategy in Ethiopia ............................ 9 PART I PRIMARY EDUCATION .............................................................................................. 11 A. Context Analysis: Gaps and challenges ........................................................................................ 11 Teachers................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Curricula .................................................................................................................................................................. 12 MoE Expertise ...................................................................................................................................................... -

The Impact of Roads on Land-Use Change in Ethiopia: Evidence from Satellite Data

The Impact of Roads on Land-Use Change in Ethiopia: Evidence from Satellite Data By: Ariana Brynn Vaisey Honors Thesis Economics Department University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 2016 Approved: ___________________________ Dr. Simon Alder Ariana Vaisey 2 Abstract Using satellite-based land cover data for Ethiopia, I examine the relationship between travel costs and the spatial allocation of economic activity. In analyzing a cross-section of land cover data for all of Ethiopia in 2005/2006, I find that proximity to market is positively associated with land being devoted to agriculture, when controlling for soil quality and climatic factors. Additionally, I examine the change in land cover associated with the construction of the Addis Ababa-Adama expressway, using panel data on land cover in a 40-km buffer of the expressway for 2009 and 2016. I find that proximity to the expressway increases the likelihood of a transition in land cover type, both into and out of agriculture. On average, the expressway reduced the likelihood of agricultural land cover for land parcels within an inner buffer of the expressway in the period after it opened. This study contributes to previous literature by employing high spatial resolution GIS data that has not been previously applied to studies of economic geography, by examining data from the African continent – where little empirical work on transportation infrastructure and land cover change has been done –, and by using a comprehensive measure of market access to assess transportation costs. Ariana Vaisey 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Simon Alder, for providing invaluable guidance in formulating a research question, using geographic information systems software to collect data, and building a model to test my hypotheses. -

TANA FORUM REPORT No Retreat, No Surrender

2017 TANA FORUM REPORT No Retreat, No Surrender 2017 TANA FORUM REPORT No Retreat, No Surrender Copyright © 2017 Tana Forum Secretariat at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reproduced as long as the Tana Forum Secretariat at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University is acknowledged as the source. Preface Dear friends of the Tana Forum, Since 2012, it has been a tradition to provide our participants and readers with in-depth knowledge on the theme of each year. The State of Peace and Security in Africa report, presented annually by the Tana Forum Chairperson, has become a significant contribution to the field of peace and security. This year’s trends will fuel your thoughts on the mixture of progress and obstacles facing the sector today: • Various security indices on armed conflicts (total number, spread/distribution and trend analysis) • The lack of progress of peace agreements • Atomised violence and low intensity conflicts • An overview of African interventions in peace and security • Containment and rollbacks of violence extremism, focusing on three case studies: Boko Haram, Al-Shabaab and the Islamic State (IS) • Political protests and riots It is also important to highlight some of the most salient security challenges: 1. In 2016, the threats posed by violent extremist groups were neutralized or reduced, with the main epicentres of attacks in Africa including Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin area; al-Shabaab in Somalia and Kenya; and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), Ansar-Dine, Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s katibat (battalion) al-Murabitun and IS elements in Northern Mali and the Sahel region; and IS in Libya (Sirte and parts of Benghazi), Tunisia and Egypt. -

Urban Refugee Economies: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Urban refugee economies: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Alison Brown, Peter Mackie, Kate Dickenson and Tegegne Gebre-Egziabher Working Paper Urban environments Keywords: March 2018 Refugees, Informal economy, Post-conflict reconstruction, Local economic development About the authors Acknowledgements Alison Brown, Cardiff University, Our thanks to Addis Ababa University, in particular to Tegegne www.cardiff.ac.uk/people/view/363219-brown-alison, Gebre-Egziabher’s research assistants, the Administration for [email protected] Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA) and the Danish Refugee Council who facilitated this research. Thanks also to Jennifer Peter Mackie, Cardiff University, Riggan, Arcadia University, and Kemisso Alebachew, Addis Ababa www.cardiff.ac.uk/people/view/363257-mackie-peter University, for their support. Most significantly, our thanks to the Kate Dickenson, Cardiff University, many refugees who participated in this study http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/people/view/515995-Kate-Dickenson Tegegne Gebre-Egziabher, Addis Ababa University, About the Urban Crises Learning Fund www.aau.edu.et/idpr/tegegne Urban areas are increasingly the sites of humanitarian crises, from natural disasters to conflict and displacement. IIED is leading Produced by IIED’s Human Settlements a three-year programme of research, documentation of past experiences, development of tools and guidelines, and shared Group learning across humanitarian actors and other urban stakeholders. The Human Settlements Group works to reduce poverty and IIED is working to build the knowledge and capacity to respond of improve health and housing conditions in the urban centres of humanitarian actors working in urban areas, and of urban actors Africa, Asia and Latin America. It seeks to combine this with facing humanitarian crises. -

Agricultural Prices During Drought in Ethiopia

ESSP WORKING PAPER 97 Agricultural prices during drought in Ethiopia An updated assessment using national producer data (January 2014 to June 2016) Fantu Bachewe, Feiruz Yimer, and Bart Minten This ESSP Working Paper builds on the analysis of ESSP Working Paper 88 (April 2016) by extending the period over which prices are examined through to June 2016 and expanding several components of the analysis. November 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Data and methodology............................................................................................................................................. 4 3. Agricultural prices .................................................................................................................................................... 6 3.1. Cereal prices ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 3.2. Other crops ......................................................................................................................................................... 9 3.3. Comparing recent cereal price evolution with that of a previous major -

Download the Dataset for This Study

Tessema and Tiruneh BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2020) 20:342 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02986-w RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Spatio-temporal distribution and associated factors of home delivery in Ethiopia. Further multilevel and spatial analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health surveys 2005–2016 Zemenu Tadesse Tessema1* and Sofonyas Abebaw Tiruneh2 Abstract Background: Globally, between 2012 and 2017, 80% of live births occurred at health facilities assisted by skilled health personnel. In Ethiopia, in 2016 only 26% of live births attended by skilled health personal. This study aimed to assess the spatial patterns and associated factors of home delivery in Ethiopia using 2005, 2011, and 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys. Methods: A total of 33,482 women who gave live birth in the 5 years preceding each survey were included for this study. ArcGIS version 10.7 software was used to visualize the spatial distribution of home delivery. The Bernoulli model was applied using Kilduff SaTScan version 9.6 software to identify significant purely spatial clusters for home delivery in Ethiopia. A multilevel logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with home delivery. A p-value < 0.05 was taken to declare statistically significant predictors. Results: Home delivery was declined from 94.78% in 2005, 90.05% in 2011, and 73.44% in 2016 in Ethiopia. Among the three surveys, consistently high clustering of home delivery was observed in Amhara and Southern Nations Nationalities and People’s Regions (SNNPR) of Ethiopia. In spatial scan statistics analysis, a total of 128 clusters (RR = 1.04, P-value < 0.001) in 2005, and 90 clusters (RR = 1.11, P-value < 0.001) in 2011, and 55 clusters (RR = 1.29, P-value < 0.001) in 2016 significant primary clusters were identified. -

The State of Social Safety Nets 2018

2018 The State of Social Safety Nets Nets Safety Social of State The Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The State ofSocialSafety Nets State The 2018 The State of Social Safety Nets 2018 The State of Social Safety Nets 2018 © 2018 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 21 20 19 18 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. -

Aiming for Universal Health Coverage Through Insurance in Ethiopia: State

ESID Working Paper No. 156 The political economy of health insurance enrolment in Ethiopia: Party, state and the quest for universal health coverage Tom Lavers 1 October 2020 1 The University of Manchester Email correspondence: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-912593-70-5 email: [email protected] Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID) Global Development Institute, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK www.effective-states.org The political economy of health insurance enrolment in Ethiopia: Party, state and the quest for universal health coverage Abstract Many developing countries are considering insurance as a means of pursuing universal health coverage. A key challenge to confront is how to achieve high levels of health insurance enrolment. For voluntary schemes, this entails mass awareness- raising and promotional activity, though as schemes move to compulsory enrolment, monitoring and enforcement is required. This paper focuses on Ethiopia, which is has made state health insurance for the informal sector a central pillar of its universal health coverage strategy. The paper shows that high enrolment requires particular forms of state capacity, captured here by Michael Mann’s concept of state ‘infrastructural power’. The paper draws on detailed case studies of health insurance implementation in the Tigray and Oromiya regions of Ethiopia to illustrate variation in state infrastructural power and the implications for the promotion of health insurance. The findings suggest that the potential of state health insurance as a means of promoting health access for a broad section of the population may be limited to the minority of countries or regions within countries exhibiting high levels of infrastructural power.