Yishu 60 Web.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Chen Qiulin), 25F a Cheng, 94F a Xian, 276 a Zhen, 142F Abso

Index Note: “f ” with a page number indicates a figure. Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, 81, 101, 102, 132, 271 Apartment (gongyu), 270 “......” (Chen Qiulin), 25f Apartment art, 7–10, 18, 269–271, 284, 305, 358 ending of, 276, 308 A Cheng, 94f internationalization of, 308 A Xian, 276 legacy of the guannian artists in, 29 A Zhen, 142f named by Gao Minglu, 7, 269–270 Absolute Principle (Shu Qun), 171, 172f, 197 in 1980s, 4–5, 271, 273 Absolution Series (Lei Hong), 349f privacy and, 7, 276, 308 Abstract art (chouxiang yishu), 10, 20–21, 81, 271, 311 space of, 305 Abstract expressionism, 22 temporary nature of, 305 “Academic Exchange Exhibition for Nationwide Young women’s art and, 24 Artists,” 145, 146f Apolitical art, 10, 66, 79–81, 90 Academicism, 78–84, 122, 202. See also New academicism Appearance of Cross Series (Ding Yi), 317f Academic realism, 54, 66–67 Apple and thinker metaphor, 175–176, 178, 180–182 Academic socialist realism, 54, 55 April Fifth Tian’anmen Demonstration (Li Xiaobin), 76f Adagio in the Opening of Second Movement, Symphony No. 5 April Photo Society, 75–76 (Wang Qiang), 108f exhibition, 74f, 75 Adam and Eve (Meng Luding), 28 Architectural models, 20 Aestheticism, 2, 6, 10–11, 37, 42, 80, 122, 200 Architectural preservation, 21 opposition to, 202, 204 Architectural sites, ritualized space in, 11–12, 14 Aesthetic principles, Chinese, 311 Art and Language group, 199 Aesthetic theory, traditional, 201–202 Art education system, 78–79, 85, 102, 105, 380n24 After Calamity (Yang Yushu), 91f Art field (yishuchang), 125 Agree -

Zhan Ng Enli I

ICA Press release: 15 May 2013 Zhang Enli ICA Theatre Project 16 October 2013 – 22 December 2013 The ICA is pleased to announce a unique project with Shanghai-based artist Zhang Enli. Transforming the ICA theatre with a painting covering the floor and walls, the artist will create an immersive pictorial environment. Enli’s previous paintings featured seemingly mundane urban objects such as tangled wires, empty cabinets, cargo netting and stacked cardboard boxes. As with the objects he paints, the spaces are empty rooms that show signs of decay and come complete with dirt marks. Semi-transparent layers of paint and the traces of brush strokes draw the viewer’s focus to the materiality of the painting, and in turn the newly created space. Enli always paints with artificial light in a studio located in Moganshan Road art district, an industrial compound filled with galleries and artist studios in Shanghai. Looking at the tones and colours that permeate his work this lack of natural light is evident and enhances the presence of an artificial atmosphere. Enli’s work embodies a very personal relationship with his surroundings and for the ICA he aims to stretch colours across the space 'like human skin' with thin washes of pigment creating a 'space painting.' Having grown up in the provincial town of Jilin in the north of China, Enli’s work continues to be strongly marked by his experience of this transition, 20 years ago, to the sprawling metropolis of Shanghai. He represents this extreme contrast to the smaller city he was accustomed to, not through the consumerist preoccupation so common in contemporary Chinese painting coming from its major cities, but by looking at the ordinary, unpretentious objects that surround him and the immigrants travelling from the countryside to Shanghai. -

Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 489 SO 025 360 AUTHOR Yu-ning, Li, Ed. TITLE Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM Johnson & Associates, 257 East South St., Franklin, IN 46131-2422 (paperback: $25; clothbound: ISBN-1-880938-008, $39; shipping: $3 first copy, $0.50 each additional copy). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chinese Culture; *Cultural Images; Females; Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Legends; Mythology; Role Perception; Sexism in Language; Sex Role; *Sex Stereotypes; Sexual Identity; *Womens Studies; World History; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Asian Culture; China; '`Chinese Literature ABSTRACT This book examines the ways in which Chinese literature offers a vast array of prospects, new interpretations, new fields of study, and new themes for the study of women. As a result of the global movement toward greater recognition of gender equality and human dignity, the study of women as portrayed in Chinese literature has a long and rich history. A single volume cannot cover the enormous field but offers volume is a starting point for further research. Several renowned Chinese writers and researchers contributed to the book. The volume includes the following: (1) Introduction (Li Yu- Wing);(2) Concepts of Redemption and Fall through Woman as Reflected in Chinese Literature (Tsung Su);(3) The Poems of Li Qingzhao (1084-1141) (Kai-yu Hsu); (4) Images of Women in Yuan Drama (Fan Pen Chen);(5) The Vanguards--The Truncated Stage (The Women of Lu Yin, Bing Xin, and Ding Ling) (Liu Nienling); (6) New Woman vs. -

Downloaded 4.0 License

Return to an Inner Utopia 119 Chapter 4 Return to an Inner Utopia In what was to become a celebrated act in Chinese literary history, Su Shi be- gan systematically composing “matching Tao” (he Tao 和陶) poems in the spring of 1095, during his period of exile in Huizhou. This project of 109 poems was completed when he was further exiled to Danzhou. It was issued in four fascicles, shortly after his return to the mainland in 1100.1 Inspired by and fol- lowing the rhyming patterns of the poetry of Tao Qian, these poems contrib- uted to the making (and remaking) of the images of both poets, as well as a return to simplicity in Chinese lyrical aesthetics.2 Thus far, scholarship has focused on the significance of Su Shi’s agency in Tao Qian’s canonisation. His image was transformed through Su’s criticism and emulation: Tao came to be viewed as a spontaneous Man of the Way and not just an eccentric medieval recluse and hearty drinker.3 In other words, Tao Qian’s ‘spontaneity’ was only created retrospectively in lament over its loss. The unattainability of the ideal is part and parcel of its worth. In this chapter, I will further examine what Su Shi’s practice meant for Su Shi himself. I argue that Su Shi’s active transformation of and identification with Tao Qian’s image were driven by the purpose of overcoming the tyranny of despair, deprivation and mortality. The apparent serenity of the “matching Tao” poems was therefore fundamentally paradoxical, a result of self-persua- sion. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Reflections on Anonymity and Contemporaneity in Chinese Art Beatrice Leanza

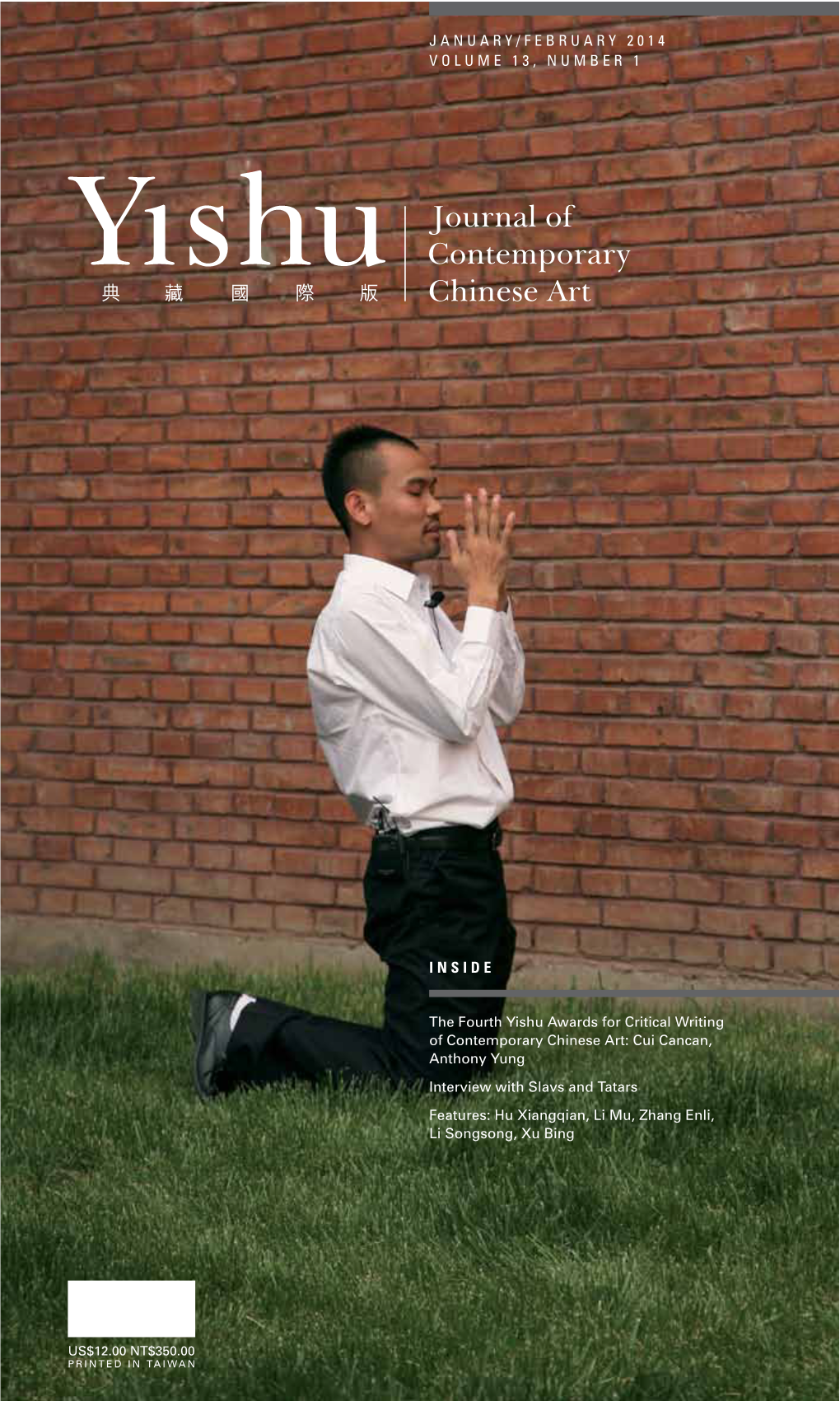

PLACE UNDER THE LINE PLACE UNDER THE LINE : july / august 1 vol.9 no. 4 J U L Y / A U G U S T 2 0 1 0 VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4 INSIDE New Art in Guangzhou Reviews from London, Beijing, and San Artist Features: Gu Francisco Wenda, Lin Fengmian, Zhang Huan The Contemporary Art Academy of China Identity Politics and Cultural Capital in Contemporary Chinese Art US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4, JULY/AUGUST 2010 CONTENTS 2 Editor’s Note 33 4 Contributors 6 The Guangzhou Art Scene: Today and Tomorrow Biljana Ciric 15 On Observation Society Anthony Yung Tsz Kin 20 A Conversation with Hu Xiangqian 46 Biljana Ciric, Li Mu, and Tang Dixin 33 An interview with Gu Wenda Claire Huot 43 China Park Gu Wenda 46 Cubism Revisited: The Late Work of Lin Fengmian Tianyue Jiang 63 63 The Cult of Origin: Identity Politics and Cultural Capital in Contemporary Chinese Art J. P. Park 73 Zhang Huan: Paradise Regained Benjamin Genocchio 84 Contemporary Art Academy of China: An Introduction Christina Yu 87 87 Of Jungle—In Praise of Distance: Reflections on Anonymity and Contemporaneity in Chinese Art Beatrice Leanza 97 Shanghai: Art of the City Micki McCoy 104 Zhang Enli Natasha Degan 97 111 Chinese Name Index Cover: Zhang Huan, Hehe Xiexie (detail), 2010, mirror-finished stainless steel, 600 x 420 x 390 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Vol.9 No.4 1 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art president Katy Hsiu-chih Chien legal counsel Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C.C. -

Creating Standards

Creating Standards Unauthenticated Download Date | 6/17/19 6:48 PM Studies in Manuscript Cultures Edited by Michael Friedrich Harunaga Isaacson Jörg B. Quenzer Volume 16 Unauthenticated Download Date | 6/17/19 6:48 PM Creating Standards Interactions with Arabic Script in 12 Manuscript Cultures Edited by Dmitry Bondarev Alessandro Gori Lameen Souag Unauthenticated Download Date | 6/17/19 6:48 PM ISBN 978-3-11-063498-3 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063906-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063508-9 ISSN 2365-9696 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019935659 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Dmitry Bondarev, Alessandro Gori, Lameen Souag, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Unauthenticated Download Date | 6/17/19 6:48 PM Contents The Editors Preface VII Transliteration of Arabic and some Arabic-based Script Graphemes used in this Volume (including Persian and Malay) IX Dmitry Bondarev Introduction: Orthographic Polyphony in Arabic Script 1 Paola Orsatti Persian Language in Arabic Script: The Formation of the Orthographic Standard and the Different Graphic Traditions of Iran in the First Centuries of -

2018 ASIA 2607 Self and Society

ASIA 2607: Self and Society in Pre-modern Chinese Literature MWF 12:10-1:00 Furman Hall 007 Office Hours: Wed 1:45-3:45 Buttrick 260 Prof. Guojun Wang ([email protected]) (Prior knowledge of Chinese language or literature is NOT required) Course Description: What is the Chinese tradition? What is the traditional China? How can such a millennia-long civilization enrich our experience as individual persons in modern society? Through reading Chinese literature, we will together explore these questions. In this course, you will learn about the major intellectual traditions, literary texts, and authors in pre-modern China (ca. 17th century BCE to 20th century CE). The readings follow a chronological order, but in each period we focus on some particular themes revolving around self and society. In turn we will discuss early writings on man and nature, the birth of the poetic self, China as an open empire, Chinese ethnicity, vernacular literature and commercial culture, and the modern view of the Chinese tradition. Through this course, you will become familiar with China’s intellectual traditions and literary history, hone your skills of close reading, and learn to think and write critically. ASIA 2607 Self and Society in Pre-modern Chinese Literature 2 Class meets three times a week. MW meetings usually include a 30-minute lecture followed by a 20-minute discussion. Friday meetings are usually discussion sessions. The readings for each class average about 25 pages (I will designate sections to focus on if more readings are assigned). All readings are in English. Class is taught in English. -

The Poetry of Zhai Yongming 翟永明 1982-1995

The Poetry of Zhai Yongming 翟永明 1982-1995 Zhai Yongming was born in Chengdu, Sichuan province, in 1955. She as one of the instigators of the “Black Tornado” of woman’s poetry that swept China’s poetry scene in 1986-1989. This came about as a reaction among other woman poets to the official publication of poems from her series <Woman> and other poems during this period. In fact, <Woman> was written in 1984, and poems in the series appeared in Sichuan’s unofficial poetry journals and others outside the province in 1985. The series was officially published in book form (with other poems) in 1989. Since the 1980s, Zhai has maintained a position as one of China’s most prominent poets, being a frequent guest at conferences and festivals in Europe and North America since spending over a year travelling in the West with her then artist-husband in the early 1990s. 1) I Have a Broom [ 我有了一把扫帚] 2) Woman [ 女人] I. #1 A Premonition [ 预感] II. #3 An Instant [ 瞬间] III. #6 The World [ 世界] IV. #7 Mother [ 母亲] V. #9 Anticipation [ 憧憬] VI. #10 Nightmare [ 噩梦] VII. #11 Monologue [ 独白] VIII. #14 July [ 七月] IX. #17 Human Life [ 人生] X. #18 Silence [ 沉默] XI. #20 The Finish [ 结束] 3) Peaceful Village [ 静安庄] I. The First Month [ 第一月] II. The Seventh Month [ 第七月] III. The Twelfth Month [ 第十二月] 4) The Black Room [ 黑房间] 5) At This Very Moment [ 此时此刻] 6) The Red Room [红房间] 7) You've Cut Off My Hair [ 头发被你剪去] 8) Landlord! Landlord! [ 房东!!!房东!房东!!!] 9) Death's Design [ 死亡的图案] I. -

2004 V03 03 Wu H P005.Pdf

: Figure 1. Marc Riboud, A Student in the Central Academy of Fine Arts Making an Image of Mao Zedong, 1957, black-and-white photography. Courtesy of Chambers Fine Art The exhibition Intersection,presented at Chambers Fine Art in New York City in June 2004, deals with a fundamental issue in contemporary Chinese art: the interrelationship between photography and painting. It is fundamental because few oil painters and photographers in post-Cultural Revolution China can escape this interrelationship which has influenced and even controlled their art in different ways and on multiple levels. From the 1960s through the 1980s, photography provided painting with a state sanctioned reality to depict (although the content of this reality changed greatly over time), while most “experimental photographers” (shiyan sheyingjia) that emerged in the 1990s and early 2000s were first trained as painters or graphic artists. How do painting and photography interact with each other in today’s Chinese art? To Chen Danqing, one of the six artists featured in this exhibition, “copying [photographs in oil] is not to imitate other people’s language. Like playing musical compositions, copying is itself a language.”The other five artists each answer the question differently; but all have problematized the painting/photography relationship in their works. By doing so, these artists—three photographers and three oil painters—demonstrate how this relationship has become a shared focus of their artistic experi- mentation. To understand the experimental nature of their works, however, we need to briefly reflect upon the connections between painting and photography in Chinese art since the 1960s. *** “Painting from photographs” became a legitimate artistic practice during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), when numerous paintings—portraits of Mao Zedong and his wife Jiang Qing, heroic images of the revolutionary masses, and narrative pictures of the Party’s glorious history—were Figure 2. -

Ethnohistory of the Qizilbash in Kabul: Migration, State, and a Shi'a Minority

ETHNOHISTORY OF THE QIZILBASH IN KABUL: MIGRATION, STATE, AND A SHI’A MINORITY Solaiman M. Fazel Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology Indiana University May 2017 i Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Raymond J. DeMallie, PhD __________________________________________ Anya Peterson Royce, PhD __________________________________________ Daniel Suslak, PhD __________________________________________ Devin DeWeese, PhD __________________________________________ Ron Sela, PhD Date of Defense ii For my love Megan for the light of my eyes Tamanah and Sohrab and for my esteemed professors who inspired me iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This historical ethnography of Qizilbash communities in Kabul is the result of a painstaking process of multi-sited archival research, in-person interviews, and collection of empirical data from archival sources, memoirs, and memories of the people who once live/lived and experienced the affects of state-formation in Afghanistan. The origin of my study extends beyond the moment I had to pick a research topic for completion of my doctoral dissertation in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University. This study grapples with some questions that have occupied my mind since a young age when my parents decided to migrate from Kabul to Los Angeles because of the Soviet-Afghan War of 1980s. I undertook sections of this topic while finishing my Senior Project at UC Santa Barbara and my Master’s thesis at California State University, Fullerton. I can only hope that the questions and analysis offered here reflects my intellectual progress. -

Thatched Cottage in a Fallen City the Poetics and Sociology of Survival Under the Occupation

European Journal European Journal of of East Asian Studies 19 (2020) 209–236 East Asian Studies brill.com/ejea Thatched Cottage in a Fallen City The Poetics and Sociology of Survival under the Occupation Zhiyi Yang Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany [email protected] Abstract This article examines the construction of lyric identities by Li Xuanti, a classical- style poet, cultural celebrity and prominent civil servant in collaborationist regimes based in Nanjing during the Second Sino-Japanese War. It argues that Li used his poetry to explore the confusion, ambivalence and sense of cultural pride while liv- ing with the occupiers. Despite his collaboration, a frequent identity that appears in Li’s poetry is that of a yimin (loyalist), who has retreated to the inner world of reclu- sion. With the progress of the war, however, another identity eventually emerged in Li’s poetry, namely that of a patriot. Historical allusions in Li’s poems thus acquire double- entendre, expressing his ambivalent loyalty. Li was also at the social centre of a group of like-minded collaborators and accommodators in Nanjing, bound by their common practice of classical-style poetry and arts.Their community thus becomes a special case of study for the sociology of survival under the Japanese occupation. Keywords Li Xuanti – collaboration – accommodation – Japanese occupation – classical-style Chinese poetry – Second Sino-Japanese War In September 1940, Li Xuanti 李宣倜 (1888–1961), chief of the Bureau of Engrav- ing and Printing in the collaborationist Reorganised National Government (rng) in Nanjing, was awarded a vacant two-storey house in the Three-Steps- Two-Bridges (Sanbu liangqiao 三步兩橋) residential quarter.