Souris River Study Unit 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Souris R1ve.R Investigation

INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION REPORT ON THE SOURIS R1VE.R INVESTIGATION OTTAWA - WASHINGTON 1940 OTTAWA EDMOND CLOUTIER PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1941 INTERNATIONAT, JOINT COMMISSION OTTAWA - WASHINGTON CAKADA UNITEDSTATES Cllarles Stewrt, Chnirmun A. 0. Stanley, Chairman (korge 11'. Kytc Roger B. McWhorter .J. E. I'erradt R. Walton Moore Lawrence ,J. Burpee, Secretary Jesse B. Ellis, Secretary REFERENCE Under date of January 15, 1940, the following Reference was communicated by the Governments of the United States and Canada to the Commission: '' I have the honour to inform you that the Governments of Canada and the United States have agreed to refer to the International Joint Commission, underthe provisions of Article 9 of theBoundary Waters Treaty, 1909, for investigation, report, and recommendation, the following questions with respect to the waters of the Souris (Mouse) River and its tributaries whichcross the InternationalBoundary from the Province of Saskatchewanto the State of NorthDakota and from the Stat'e of NorthDakota to the Province of Manitoba:- " Question 1 In order to secure the interests of the inhabitants of Canada and the United States in the Souris (Mouse) River drainage basin, what apportion- ment shouldbe made of the waters of the Souris(Mouse) River and ita tributaries,the waters of whichcross theinternational boundary, to the Province of Saskatchewan,the State of North Dakota, and the Province of Manitoba? " Question ,$! What methods of control and operation would be feasible and desirable in -

Reconstruction of Glacial Lake Hind of Southwestern

Journal of Paleolimnology 17: 9±21, 1997. 9 c 1997 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in Belgium. Reconstruction of glacial Lake Hind in southwestern Manitoba, Canada C. S. Sun & J. T. Teller Department of Geological Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3T 2N2 Received 24 July 1995; accepted 21 January 1996 Abstract Glacial Lake Hind was a 4000 km2 ice-marginal lake which formed in southwestern Manitoba during the last deglaciation. It received meltwater from western Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and North Dakota via at least 10 channels, and discharged into glacial Lake Agassiz through the Pembina Spillway. During the early stage of deglaciation in southwestern Manitoba, part of the glacial Lake Hind basin was occupied by glacial Lake Souris which extended into the area from North Dakota. Sediments in the Lake Hind basin consist of deltaic gravels, lacustrine sand, and clayey silt. Much of the uppermost lacustrine sand in the central part of the basin has been reworked into aeolian dunes. No beaches have been recognized in the basin. Around the margins, clayey silt occurs up to a modern elevation of 457 m, and ¯uvio-deltaic gravels occur at 434±462 m. There are a total of 12 deltas, which can be divided into 3 groups based on elevation of their surfaces: (1) above 450 m along the eastern edge of the basin and in the narrow southern end; (2) between 450 and 442 m at the western edge of the basin; and (3) below 442 m. The earliest stage of glacial Lake Hind began shortly after 12 ka, as a small lake formed between the Souris and Red River lobes in southwestern Manitoba. -

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota By RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Prepared as part of the program of the Department of the Interior *Jfor the development-L of*J the Missouri River basin UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $3 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ _____-_-_________________--_--____---__ 1 Pre- Wisconsin nonglacial deposits, ______________ 41 Scope and purpose of study._________________________ 2 Stratigraphic sequence in Nebraska and Iowa_ 42 Field work and acknowledgments._______-_____-_----_ 3 Stream deposits. _____________________ 42 Earlier studies____________________________________ 4 Loess sheets _ _ ______________________ 43 Geography.________________________________________ 5 Weathering profiles. __________________ 44 Topography and drainage______________________ 5 Stream deposits in South Dakota ___________ 45 Minnesota River-Red River lowland. _________ 5 Sand and gravel- _____________________ 45 Coteau des Prairies.________________________ 6 Distribution and thickness. ________ 45 Surface expression._____________________ 6 Physical character. _______________ 45 General geology._______________________ 7 Description by localities ___________ 46 Subdivisions. ________-___--_-_-_-______ 9 Conditions of deposition ___________ 50 James River lowland.__________-__-___-_--__ 9 Age and correlation_______________ 51 General features._________-____--_-__-__ 9 Clayey silt. __________________________ 52 Lake Dakota plain____________________ 10 Loveland loess in South Dakota. ___________ 52 James River highlands...-------.-.---.- 11 Weathering profiles and buried soils. ________ 53 Coteau du Missouri..___________--_-_-__-___ 12 Synthesis of pre- Wisconsin stratigraphy. -

Geomorphic and Sedimentological History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin

Electronic Capture, 2008 The PDF file from which this document was printed was generated by scanning an original copy of the publication. Because the capture method used was 'Searchable Image (Exact)', it was not possible to proofread the resulting file to remove errors resulting from the capture process. Users should therefore verify critical information in an original copy of the publication. Recommended citation: J.T. Teller, L.H. Thorleifson, G. Matile and W.C. Brisbin, 1996. Sedimentology, Geomorphology and History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin Field Trip Guidebook B2; Geological Association of CanadalMineralogical Association of Canada Annual Meeting, Winnipeg, Manitoba, May 27-29, 1996. © 1996: This book, orportions ofit, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission ofthe Geological Association ofCanada, Winnipeg Section. Additional copies can be purchased from the Geological Association of Canada, Winnipeg Section. Details are given on the back cover. SEDIMENTOLOGY, GEOMORPHOLOGY, AND HISTORY OF THE CENTRAL LAKE AGASSIZ BASIN TABLE OF CONTENTS The Winnipeg Area 1 General Introduction to Lake Agassiz 4 DAY 1: Winnipeg to Delta Marsh Field Station 6 STOP 1: Delta Marsh Field Station. ...................... .. 10 DAY2: Delta Marsh Field Station to Brandon to Bruxelles, Return En Route to Next Stop 14 STOP 2: Campbell Beach Ridge at Arden 14 En Route to Next Stop 18 STOP 3: Distal Sediments of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 18 En Route to Next Stop 19 STOP 4: Flood Gravels at Head of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 24 En Route to Next Stop 24 STOP 5: Stott Buffalo Jump and Assiniboine Spillway - LUNCH 28 En Route to Next Stop 28 STOP 6: Spruce Woods 29 En Route to Next Stop 31 STOP 7: Bruxelles Glaciotectonic Cut 34 STOP 8: Pembina Spillway View 34 DAY 3: Delta Marsh Field Station to Latimer Gully to Winnipeg En Route to Next Stop 36 STOP 9: Distal Fan Sediment , 36 STOP 10: Valley Fill Sediments (Latimer Gully) 36 STOP 11: Deep Basin Landforms of Lake Agassiz 42 References Cited 49 Appendix "Review of Lake Agassiz history" (L.H. -

The Generation of Mega Glacial Meltwater Floods and Their Geologic

urren : C t R gy e o s l e o r a r LaViolette, Hydrol Current Res 2017, 8:1 d c y h H Hydrology DOI: 10.4172/2157-7587.1000269 Current Research ISSN: 2157-7587 Research Article Open Access The Generation of Mega Glacial Meltwater Floods and Their Geologic Impact Paul A LaViolette* The Starburst Foundation, 1176 Hedgewood Lane, Niskayuna, New York 12309, United States Abstract A mechanism is presented explaining how mega meltwater avalanches could be generated on the surface of a continental ice sheet. It is shown that during periods of excessive climatic warmth when the continental ice sheet surface was melting at an accelerated rate, self-amplifying, translating waves of glacial meltwater emerge as a distinct mechanism of meltwater transport. It is shown that such glacier waves would have been capable of attaining kinetic energies per kilometer of wave front equivalent to 12 million tons of TNT, to have achieved heights of 100 to 300 meters, and forward velocities as great as 900 km/hr. Glacier waves would not have been restricted to a particular locale, but could have been produced wherever continental ice sheets were present. Catastrophic floods produced by waves of such size and kinetic energy would be able to account for the character of the permafrost deposits found in Alaska and Siberia, flood features and numerous drumlin field formations seen in North America, and many of the lignite deposits found in Europe, Siberia, and North America. They also could account for how continental debris was transported thousands of kilometers into the mid North Atlantic to form Heinrich layers. -

Sedimentology and Stratigraphy of Glacial Lake Souris, North Dakota: Effects of a Glacial-Lake Outburst Mark L

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 1988 Sedimentology and Stratigraphy of Glacial Lake Souris, North Dakota: effects of a glacial-lake outburst Mark L. Lord University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Lord, Mark L., "Sedimentology and Stratigraphy of Glacial Lake Souris, North Dakota: effects of a glacial-lake outburst" (1988). Theses and Dissertations. 183. https://commons.und.edu/theses/183 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEDIMENTOLOGY AND STRATIGRAPHY OF GLACIAL LAKE SOURIS, NORTH DAKOTA: EFFECTS OF A GLACIAL-LAKE OUTBURST by Mark L. Lord Bachelor of Science, State University of New York College at Cortland, 1981 Master of Science University of North Dakota, 1984 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Grand Forks, North Dakota August 1988 l I This Dissertation submitted by Mark L. Lord in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the University of North Dakota has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done, and is hereby approved. (Chairperson) This Dissertation meets the standards for appearance and conforms to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of North Dakota, and is hereby approved. -

National Advisory Committee on Research in the Geological Sciences

6 -01 NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON RESEARCH IN THE GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES SIXTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT 1965-66 ANNUAL REVIEW AND REPORTS OF SUBCOMMITTEES Published by the Geological Survey of Canada as GSC Paper 66 -61 MANUSCRIPT AI'1D National Advisory Cf\ DT()':~AO~JY - APR 3 1967 HR · 1967 Price, 5 D ce nts 1967 SECTION Comn-.:!:~ee SIXTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT 1965-66 ANNUAL REVIEW AND REPORTS OF SUBCOMMITTEES @ Crown C opyrights reserved Availa b le by mail from the Queen' s Printer, Otta wa from the Geologi cal Survey of Canada, 601 B ooth St. , Ottawa and a t th e fo llowing Can a dian Governm ent book s h op s: OTTAWA Daly Building, Corner Mackenzie and Rideau TORONTO 221 Yonge Street MONTREAL /Eterna-Vie Building, 1182 St. Catherine St. West WINNIPEG Mall Center Building, 499 Portage Avenue VANCOUVER 657 Granville Avenue HALIFAX 1737 Barrington Street or through your bookseller A deposit copy of this publication is also available for reference in public libraries across Canada Price, 50 cents Cat. No. M44-66-61 Price subject to change without notice ROGER D UHAMEL, F.R.S.C. Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa, Canada 1967 CONTENTS Page MEMBERS OF COMMITTEE . • . • . • • . • . • . • . • • . vii Executive Committee . • . • . • . • • . • • • • . • . viii Projects Subcommittee . • . • . • . • . • • . • • • • • • • • . • . • • • • ix THE YEAR IN REVIEW •.....•.•••••...••••......•..•..•..•..•.• Research grants to universities .•.•••...••.........•....••• Comprehensive studies of Canadian sulphide • • . • . • • . • . • . • . • Z Storage and retrieval of geological data . • . • . • • • . • 3 Geochemical prospecting symposium........................ 6 International Union of Geological Sciences . • . • . • • . • • . • . • . 6 Summary statements and discussion of subcommittee reports.. 7 Changes in personnel of committee ....................... 13 SUBCOMMITTEE REPORTS..................................... 14 Geophysical methods applied to geological problems . -

Geology O F Renville and Ward Counties North

ISSN : 0546 - 500 1 GEOLOGY O F RENVILLE AND WARD COUNTIES NORTH DAKOTA by John P . Blueml e BULLETIN 50 - PART 1 NORTH DAKOTA INDUSTRIAL COMMISSIO N GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIVISIO N COUNTY GROUNDWATER STUDIES 11 - PART 1 NORTH DAKOTA STATE WATER COMMISSIO N Prepared by the North Dakota Geological Surve y in cooperation with the North Dakota State Water Commission, the United States Geological Survey, and Renville and Ward Counties Water Management District s Printed by Quality Printing Service 1989 CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT v i INTRODUCTION 1 Purpose 1 Previous Work 1 Methods of Study 2 Acknowledgments 3 Regional Topography and Geology 3 STRATIGRAPHY 6 General Statement 6 Cretaceous and Tertiary Rocks 8 Configuration of the Bedrock Surface 1 0 Pleistocene Sediment 1 2 Glacial Stratigraphy 1 7 Snow School Formation 20 Blue Hill Deposits 20 Younger Glacial Deposits 2 2 Holocene Sediment 24 GEOMORPHOLOGY 26 General Description 2 6 Glacial Landforms 28 Collapsed Glacial Topography 28 Waterworn Topography 32 Sllopewash-Eroded Topography 33 Glacial Lake Landforms 33 Fluvial Landforms 3 5 Spillways 3 5 Overridden Fluvial Deposits 39 Other Glaciofluvial Deposits 39 Eskers and Kames 409 PLEISTOCENE FOSSILS 40 GEOLOGIC HISTORY 41 iii CONTENTS--continued Page ECONOMIC GEOLOGY 52 Lignite 52 Gravel and Sand 53 Hydrocarbons 53 Potash 54 Halite 54 REFERENCES 56 ILLUSTRATION S Figure Page 1. Physiographic map of North Dakota showing the location of Renvill e and Ward Counties 5 2. Stratigraphic column for Renvill e and Ward Counties 7 3. Subglacial geology and topograph y of Renville and Ward Counties 1 1 4. Thickness of the Coleharbor Grou p deposits in Renville and War d Counties 1 3 5. -

Fishes of the Dakotas

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020 Fishes of the Dakotas Kathryn Schlafke South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Schlafke, Kathryn, "Fishes of the Dakotas" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3942. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3942 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FISHES OF THE DAKOTAS BY KATHRYN SCHLAFKE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Major in Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences Specialization in Fisheries Science South Dakota State University 2020 ii THESIS ACCEPTANCE PAGE Kathryn Schlafke This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the master’s degree and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. Brian Graeb, Ph.D. Advisor Date Michele R. Dudash Department Head Date Dean, Graduate School Date iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my advisors throughout this project, Dr. Katie Bertrand and Dr. Brian Graeb for giving me the opportunity to work towards a graduate degree at South Dakota State University. -

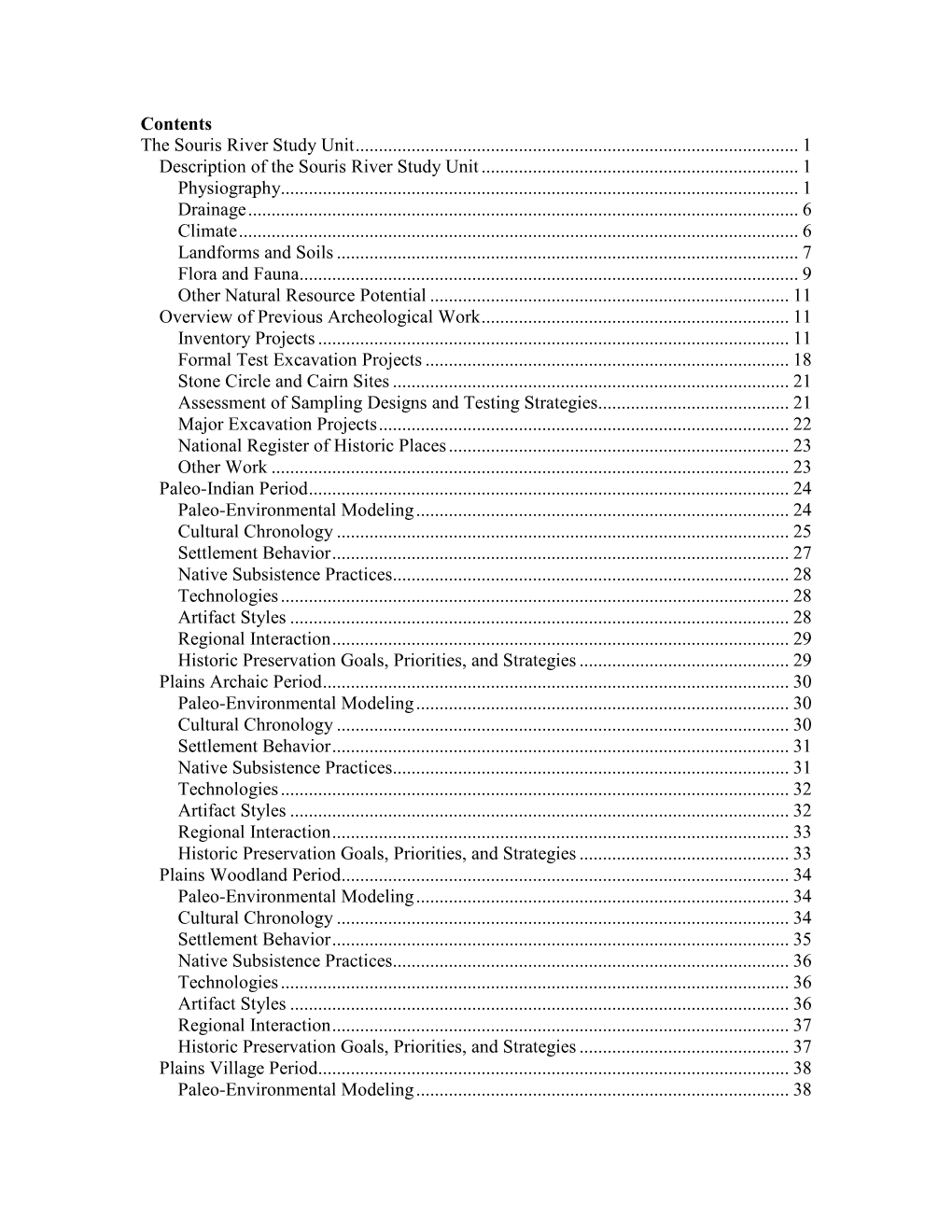

The Souris River Study Unit

The Souris River Study Unit.................................................................................11.1 Description of the Souris River Study Unit ......................................................11.1 Physiography ................................................................................................ 11.6 Drainage ....................................................................................................... 11.6 Climate.......................................................................................................... 11.7 Landforms and Soils..................................................................................... 11.8 Floodplains ............................................................................................... 11.8 Terraces .................................................................................................... 11.9 Valley Walls.............................................................................................. 11.9 Alluvial Fans........................................................................................... 11.10 Upland Plains ......................................................................................... 11.10 Flora and Fauna ......................................................................................... 11.10 Other Natural Resource Potential............................................................... 11.11 Overview of Previous Archeological Work .....................................................11.12 Inventory -

Surface Water Supply of the United States

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRKCTOB WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 285 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1910 - PAET V. HUDSON BAY AND UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF M. 0. LEIGHTON BY ROBERT FOLLANSBEE, A. H. BORTON AND G. C. STEVENS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR WATER- SUPPLY PAPER 285 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1910 PART V. HUDSON BAY AND UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF M. 0. LEIGHTON BY ROBERT FOLLANSBEE, A. H. HORTON AND G. C. STEVENS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction.............................................................. 7 Authority for investigations................................. c........... 7 Scope of investigations.................................................. 8 Publications................................................."......... 9 Definition of terms..................................................... 12 Convenient equivalents................................................ 12 Explanation of data.................................................... 13 Accuracy and reliability of field data and comparative results............. 15 Cooperative data...................................................... 17 Cooperation and acknowledgements...................................... 18 Division of work...................................................... 19 Gaging stations maintained -

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1909 Part V

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 265 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1909 PART V. HUDSON BAY AND UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER BASINS PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF M. 0. LEIGHTON BY ROBERT FOLLANSBEE, A. H. HORTON AND R. H. BOLSTER WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 265 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1909 PART V. HUDSON BAY AND UPPER MISSISSIPPI R1YER BASINS PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF M. 0. LEIGHTON BY ROBERT FOLLANSBEE, A. H. HORTON AND R. H. BOLSTER WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 CONTENTS. Introduction............................................................. 7 Authority for investigations............................................. 7 Scope of investigations.................................................. 8 Purposes of the work.................................................. 9 Publications.......................................................... 10 Definition of terms..................................................... 13 Convenient equivalents................................................ 14 Explanation of tables................................................... 15 Field methods of measuring stream flow................................. 16 Office methods of computing and studying discharge and run-off.......... 22 Accuracy and reliability of field data and comparative results............. 26 Use of the