Books for Daily Life: Household, Husbandry, Behaviour 514 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squanto's Garden

© 2006 Bill Heid Contents An Introduction to Squanto’s Garden...4 Chapter One ...6 Squanto and the Pilgrims:...6 Squanto’s History ...7 The First Meeting...12 Squanto and the Pilgrims...14 The First Thanksgiving...15 Chapter Two...18 The Soil Then...18 The Geological History of Plymouth...18 The Land Before the Pilgrims...19 The Land of New Plymouth...21 Chapter Three...23 Why Did Squanto’s Methods Work?...23 Tastes Better, Is Better...25 Chapter Four...28 The Soil Today and What It Produces...28 Chapter Five...31 Squanto’s Garden Today...31 Assessing Your Soil and Developing a Plan...31 What to Grow...34 Garden Design...35 Wampanoag...36 Wampanoag...37 Hidatsa Gardens...38 Hidasta...39 Zuni Waffle Garden...40 Zuni Waffle Garden...41 Caring for Your Garden...42 Recipes...43 Conclusion-Squanto’s Legacy...49 Resources...51 An Introduction to Squanto’s Garden When the Pilgrims first came to America, they nearly starved because of insufficient food. It was with the help of a Native American they knew as Squanto that they learned to properly cultivate the land so that they could survive and flourish. All of that might seem quite removed from your own gardening endeavors, however there is much to be learned from those historical lessons. What was the soil like then? How did the soil affect the food being grown? What techniques were used to enrich the soil? Why is it that the Pilgrims, being from a more technologically advanced society, needed the help of the Native Americans to survive? Whether you are an experienced gardener, or just starting out, “Squanto’s Garden” has plenty to teach you. -

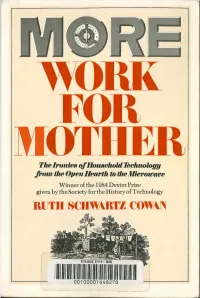

More Work for Mother

The It--onies ofHousehohl'JeehnowgiJ ft--om the Open Heat--th to the Miet--owave Winner of the 1984 Dexter Prize given by the Society for the History of Technology -RUTH SCHWARTZ COWAN ETHICS ETH·- BIB II II 111111 II II II llllllllllllll II 00100001648270 More Work for Mother MORE WORK FOR MOTHER The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave Ruth Schwartz Cowan • BasicBooks- A Division of HarperCollinsPub/ishen Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cowan, Ruth Schwartz, 1941- More work for mother. Bibliography: p. 220 Includes index. 1. Horne economics-United States-History. 2. Household appliances-United States-History. 3. Housewives-United States-History I. Title. II. Title: Household technology from the open hearth to the microwave. TX23.C64 1983 640'.973 83-70759 ISBN 0-465-04731-9 (cloth) ISBN 0-465-04732-7 (paper) Copyright © 1983 by Basic Books, Inc. Printed in the United States of America Designed by Vincent Torre 10 9 8 7 For Betty Schwartz and Louis E. Schwartz with love Contents PICTURE ESSAYS ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS XI Chapter 1 An Introduction: Housework and Its Tools 3 Chapter 2 Housewifery: Household Work and Household Tools under Pre-Industrial Conditions 16 Housewifery and the Doctrine of Separate Spheres 18 Household Tools and Household Work 20 The Household Division of Labor 26 The Household and the Market Economy 31 Conclusion 3 7 Chapter 3 The Invention of Housework: The Early Stages of Industrialization 40 Milling Flour and Making Bread 46 The Evolution of the Stove 53 More Chores -

Digesting the Complexities of Cake in Australian Society - After a Long and Textured British-European History

Digesting the complexities of cake in Australian society - after a long and textured British-European history The how and why of cake consumption in contemporary Australia ~ A Research Project by Jessica Graieg-Morrison a1641657 ~ 1. Introduction Answering the questions of how and why people choose and consume particular foods is a complex undertaking. This essay will attempt to examine the historical development of cake to determine its role on the plates and in the minds of Australian consumers. Cake is, some argue, an unnecessary food; however, there are many cultural and social events that, seemingly, cannot occur without it present. Why has this mixture of ‘special’ ingredients so long enchanted humans and become central to numerous celebrations and cultural rituals? From ancient times sweet creations have been developed using available resources, with technological development and world travel contributing to the significant development of cake offerings available today. Whatever the age, it is cake that is used to bring people together in celebration as communities mark important cultural and personal events. As time passed and people moved around the globe, cake recipes were enriched with new meanings, ideas and symbolism. As a relatively young country, Australia was taught to bake and eat cake by European immigrants, particularly the British. Our lack of a unique cultural cuisine has seen the adoption of eating patterns from a range of international sources. Sifting through stories about cake from Great Britain, mainland Europe, America and, finally, Australia, this essay will seek to examine the cultural phenomenon of cake, particularly in contemporary Australian society. 2. What is cake? The word ‘cake’ has two slightly different, albeit related, definitions. -

Renaissance Food from Rabelais to Shakespeare

RENAISSANCE FOOD FROM RABELAIS TO SHAKESPEARE Renaissance Food from Rabelais to Shakespeare Culinary Readings and Culinary Histories Edited by JOAN FITZPATRICK Loughborough University, UK ASHGATE © The editor and contributors 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Joan Fitzpatrick has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Renaissance food from Rabelais to Shakespeare: culinary readings and culinary histories. 1. Food habits - Europe - History - 16th century. 2. Food habits - Europe - History- 17th century. 3. Food habits in literature. 4. Diet in literature. 5. Cookery in literature. 6. Food writing - Europe - History 16th century. 7. Food writing - Europe - History 17th century. 8. European literature Renaissance, 1450-1600 - History and criticism. 9. European literature - 17th century - History and criticism. 1. Fitzpatrick, Joan. 809.9'33564'09031-dc22 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Renaissance food from Rabelais to Shakespeare: culinary readings and culinary histories I edited by Joan Fitzpatrick. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7546-6427-7 (alk. paper) 1. European literature-Renaissance, l450-1600-History and criticism. 2. Food in literature. 3. Food habits in literature. -

The British Origins of the First American Cookbook: a Re-Evaluation of Amelia Simmons’ American Cookery (1796)

CORE brought to you by Pobrane z czasopisma New Horizons in English Studies http://newhorizons.umcs.pl Data: 20/11/2019 22:19:35 New Horizons in English Studies 3/2018 CULTURE & MEDIA • View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Anna Węgiel GRADUATE SCHOOL FOR SOCIAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF PHILOSOPHY AND SOCIOLOGY POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES [email protected] The British Origins of The First American Cookbook: A Re-evaluation of Amelia Simmons’ American Cookery (1796) Abstract. In 1796, the first American cookbookAmerican Cookery by Amelia Simmons was published in Hartford, Connecticut. Although many scholars referred to it as “the second declaration of American independence” the cooking patterns presented in Simmons’ book still resembled the old English tradi- tion. The purpose of this paper is to explore the British origins of the first American cookbook and to demonstrate that it is, in essence,UMCS a typical eighteenth-century English cookery book. Key Words: American Cookery, Amelia Simmons, cuisine, cookbook. American Cookery by Amelia Simmons was published in 1796, twenty years after the Declaration of Independence. In Feeding America – the Historic American Cookbook Project, scholars have argued that American Cookery deserves to be called “a second Declaration of American Independence,” as it was the first cookbook written by an American writer (Feeding America 2003). Most researchers point to certain features that make American Cookery an American cookbook. Karen Hess, one of the major food studies researchers poses a question: “what makes American Cookery so very American?” and answers that “it is precisely the bringing together of certain native American products and English culinary traditions” (Hess 1996, xv). -

The Pudding Club

FOOD & DRINK The Pudding Club It was while I was visiting my aunt and choice of seven puddings (hot and cold). the earliest recipe books: The English uncle in Gloucestershire that I first heard At the end of the evening, they then vote Huswife, Containing the Inward and of the Pudding Club. As we drove through for the best pudding of the night. Outward Virtues Which Ought to Be in a Mickleton, a small, picturesque Cotswold Puddings date back to medieval times in Complete Woman by Gervase Markham, village, my uncle pointed out the Three Britain. Steamed puddings, bread puddings which was first published in 1615. Back Ways House Hotel and told me that he’d and rice puddings are all listed in one of then, puddings often meant a dish in recently been there to take part in the which meat and or sweet ingredients, ‘Pudding Club’. Intrigued, I wanted to find often in liquid form, were encased and out more. then steamed or boiled to set the con- It turns out the Pudding Club was thought tents, these were often savoury dishes up in 1985 by the then-owners Keith and such as: black pudding, haggis, steamed Jean Turner, who felt that British puddings beef pudding or Yorkshire puddings; and it were disappearing and all that was offered has only been in the past century (around after a meal was cheesecake and black for- 1950) that it came to mean any sweet est gateau. They wanted to bring back tra- dish at the end of the meal. I imagine it ditional British puddings that were starting must be somewhat confusing for first time to fade in to history, puddings such as: visitors to the United Kingdom to look at spotted dick, treacle tart, summer pudding, a menu where they could be served a college pudding and many more. -

RESEARCH THEME: FOOD RESEARCH REPORT for the UK Estonian University of Life Sciences

CULTURE AND NATURE: THE EUROPEAN HERITAGE OF SHEEP FARMING AND PASTORAL LIFE RESEARCH THEME: FOOD RESEARCH REPORT FOR THE UK By Simon Bell and Gemma Bell Estonian University of Life Sciences November 2011 The CANEPAL project is co-funded by the European Commission, Directorate General Education and Culture, CULTURE 2007-2013.Project no: 508090-CU-1-2010-1-HU-CULTURE-VOL11 This report reflects the authors’ view and the Commission is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained herein 1. INTRODUCTION Sheep have been a major farm animal in the UK for hundreds of years and also been raised in countries such as New Zealand which were British colonies and which send considerable quantities of lamb and mutton to British markets. Food from sheep has been and remains common in British cuisine and there are a number of typical and classic dishes as well as plainer and more popular ones. These are not specifically associated with sheep farming or shepherding but are intrinsically part of British and Irish cooking generally. The term lamb is used for young fattened lambs up to one year old. The meat from a mature sheep is known as mutton. In general meat from sheep (lamb and mutton) is the main product and sheep milk is hardly used except in a very small way using non-native breeds. Owing to food hygiene regulations slaughter of sheep must be carried out in licensed abbatoirs so that the food product chain starts with hill farmers selling store lambs to lowland farmers for finishing, via the auction marts, after which these farmers sell the fat lambs or fattened cull sheep to abbatoirs where the animals are slaughtered and the carcasses sold on to butchers or, increasingly, to supermarkets which nowadays have their own quality assurance schemes. -

Recipes for Life: Seventeenth-Century Englishwomen's Household Manuals

University of Alberta Recipes for Life: Seventeenth-Century Englishwomen’s Household Manuals by Kristine Kowalchuk A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English English and Film Studies ©Kristine Kowalchuk Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract This project offers a semi-diplomatic edition of three seventeenth-century Englishwomen’s household manuals along with a Historical Introduction, Textual Introduction, Note on the Text, and Glossary. The aim of this project is multifold: to bring to light a body of unpublished manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.; to consider the household manual as an important historical form of women’s writing (despite the fact it has not received such consideration in the past); to acknowledge the role of household manuals in furthering women’s literacy; to reveal new knowledge on the history of food and medicine in England as contained in household manuals; and to discuss the unique contribution of household manuals to critical issues of authorship and book history. -

December 2013 912/236-8097 Become a Facebook Fan at “Davenport House Museum”

Isaiah Davenport House Volunteer Newsletter December 2013 www.davenporthousemuseum.org 912/236-8097 Become a Facebook fan at “Davenport House Museum” To the Inhabitants of Savannah and its Tuesday, December 3 at 10 a.m. - SHOP NEW: vicinity. – DH DOCENT HOLIDAY - Visit the DH Museum Shop to A gentleman, who has lately arrived REFRESHER/End of Year find holiday gifts. You must here from Europe, undertakes to cure Celebrations and Discussion of know we have terrific stocking all DISEASES incident to the noble 2013 Special Focus – CAKES stuffers, books and signature animal, the HORSE – corns, thrushes, AND COOKIES Savannah items. and contracted feet, completely and - 1 p.m. – 2013 Oyster Roast As a gift to you from December 1 expeditiously cured; splints sprains, Meeting through 15, DH Friends, Volun- lameness, and king hooves effectually - 6 to 8 p.m. – SAA JIs teers and Staff receive a 25% removed. He also undertakes to cure Wednesday, December 4 from 10 discount on shop purchases. the diseases of the eye, if called upon a.m. to 1 or 2 p.m. – KP win- - Gift Cards: Remember we have when they are first affected. He begs dow display creation (10 a.m.) gift cards! leave to remark, these diseases, gener- followed by wreath ornamenta- - New book: See the ally, may (if taken Care of at an early tion beautifully illus- stage) be cured IN a very short period, Thursday, December 5 from 4 to 6 trated new book and at a trifling expense. Horse Medi- p.m. – Special Tour with Hospi- Magnolias, Porch- cine, of every description, carefully tality es and Sweet Tea: prepared, and to be had on the shortest Saturday, December 7 from 5 to 7 Recipes, Stories & notice. -

English Housewives in Theory and Practice, 1500-1640

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 English housewives in theory and practice, 1500-1640 Lynn Ann Botelho Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the European History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Botelho, Lynn Ann, "English housewives in theory and practice, 1500-1640" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4293. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6177 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lynn Ann Botelho for the Master of Arts in History presented May 9, 1991. Title: English Housewives in Theory and Practice, 1500-1640. APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Ann Weikel, Chair Susan Karant-Numr Charles A Le Guin Christine Thompson Women in early modem England were expected to marry, and then to become housewives. Despite the fact that nearly fifty percent of the population was in this position, little is known of the expectations and realities of these English housewives. This thesis examines both the expectations and actual lives of middling sort and gentry women in England between 1500 and 1640. The methodology employed here was relatively simple. The first step was to determine society's expectations of a good housewife. To do so the publish housewifery 2 advice books written for women were analyzed to define a model English housewife. -

Women's Reading Habits and Gendered Genres, C.1600 – 1700

Women’s Reading Habits and Gendered Genres, c.1600 – 1700 Hannah Jeans PhD University of York History July 2019 Abstract The history of early modern reading has long been based on narratives of long-term change, tracing the move from scholarly, humanist reading habits to the leisured reading of the eighteenth century. These narratives are normatively masculine, and leave little room for women and non-elite men. The studies of women readers that have emerged have largely been based on case studies of exceptional women. This thesis, then, provides the first diachonic study of women’s reading habits in the seventeenth century, offering a fresh perspective on the chronology of early modern reading. This encompasses an exploration of women’s participatio n in certain reading habits or cultures, such as ‘active reading’ methods and the rise of news culture. Moreover, there is an examination of the connections between reading and gender. This thesis proposes that reading was often used as a signifier of gender, and that by discussing their reading women entered into a discourse about femininity and identity. The sources, drawn largely from archival research across the UK and the USA, are wide-ranging, and piece together examples of reading, and representations thereof, from a variety of different seventeenth-century Englishwomen. This is a both a recovery project, and a reimagining of the field, complicating chronologies and approaches common to previous studies of reading. Ultimately, this thesis investigates both the practice and act of reading, and the nature of the ‘woman reader’ herself. It argues that our categories of analysis need to be complicated and nuanced when discussing the history of both reading and women, and proposes that the ‘woman reader’ i s far more complex and varied than is often realised. -

The Making of Domestic Medicine: Gender, Self-Help and Therapeutic Determination in Household Healthcare in South-West England in the Late Seventeenth Century

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Stobart, Anne (2008) The making of domestic medicine: gender, self-help and therapeutic determination in household healthcare in South-West England in the late seventeenth century. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/6745/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated.