English Housewives in Theory and Practice, 1500-1640

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'A Ffitt Place for Any Gentleman'?

‘A ffitt place for any Gentleman’? GARDENS, GARDENERS AND GARDENING IN ENGLAND AND WALES, c. 1560-1660 by JILL FRANCIS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham July 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to investigate gardens, gardeners and gardening practices in early modern England, from the mid-sixteenth century when the first horticultural manuals appeared in the English language dedicated solely to the ‘Arte’ of gardening, spanning the following century to its establishment as a subject worthy of scientific and intellectual debate by the Royal Society and a leisure pursuit worthy of the genteel. The inherently ephemeral nature of the activity of gardening has resulted thus far in this important aspect of cultural life being often overlooked by historians, but detailed examination of the early gardening manuals together with evidence gleaned from contemporary gentry manuscript collections, maps, plans and drawings has provided rare insight into both the practicalities of gardening during this period as well as into the aspirations of the early modern gardener. -

1972 FAMILY TAPE CODE Variable Tape Number Location Content ------1 1-3 Study Number 768 (Wave 5) (2401) (4501-4503)

1972 FAMILY TAPE CODE Variable Tape Number Location Content -------- -------- ------- 1 1-3 Study Number 768 (Wave 5) (2401) (4501-4503) ------------------------- 2 4-7 1972 Interview Number (2402) (4504-4507) --------------------- 3 8-9 *State of Residence at time of 1972 Interview (2403) (4508-4509) --------------------------------------------- 4 10-12 *County of Residence at time of 1972 Interview (2404) (4510-4512) ---------------------------------------------- 5 13-17 *State and County of Residence at time of (2405) (4513-4517) 1972 Interview ----------------------------------------- V3 and V4 combined into one variable 6 18 Size of Largest City in PSU (2406) (4518) --------------------------- 34.2 1. SMSA: largest city 500,000 or more 22.0 2. SMSA: largest city 100,000 - 499,999 11.7 3. SMSA: largest city 50,000 - 99,999 7.2 4. Non-SMSA: largest citv 25,000 - 49,999 9.5 5. Non-SMSA: largest city 10,000 - 24,999 15.1 6. Non-SMSA: largest city under 10,000 0.2 9. N.A.; DU is not in continental U.S.A. ----- 99.9 7 19 Color of Coversheet (2407) (4519) ------------------- 75.0 0. Brown (Main Family) 3.0 1. Yellow (Split-off) 20.0 2. Blue (Main Family) 2.0 3. Pink (Split-off) ----- 100.0 * Detailed State and County Codes will be furnished on request 8 20 Whether Originally Refused in 1972 A variable (2408) (4520) to determine whether or not the respondent at first refused to be interviewed this year --------------------------------------------- 99.8 0. Never refused 0.2 1. Refused at least once 0.0 9. N.A. ----- 100.0 9 21 Whether Telephone Interview in 1972 (2409) (4521) ----------------------------------- 97.2 0. -

T\\I Summit Bank, Pays Interest at 4Oio

THE CHATHAM Vol.. X. No. |s. CHATHAM, MMI;!;!.- Col.WTY, N. J., Fi.liKlAliV So, 1', $1.50 PER YEAR, LARGE REAL OBITUARY. FIVE OUT OF SIX Serious Acci ':n! to 'i'mine Girl. Mrs. 'Michael Ryan. > \i,, M.lili'i-,1 I Mrs. Michael Hyan died at her CHARLES MflNLEY ESTATE DEAL homo, on l.iun avenue last Friday FOR LOCAL BOYS lay night. She had been ailing fur si i i i ' ,i. .1 . , .: , i lung lime, but the end came unex- REAL ESTATE RHU IMSURAHCE Minion Tract of Over Thirty Acre; .lerts of Madison Never Had asail i'l HI HV..I. i, pectedly. She leaves her husband, a laughter, Man, and two sons, Aliens COMMISSIONER OF Dfc'cDS S Id .0 a N;w York Syndicate Look-in and Dropped Three Mil.l.vil .ill.-II.I, ,i us F. and John. Mrs. Hyan \va- Wh'ch Will Explut It. ibout sixty-five years old. She was Straight Games. „'! \ .'II in I iu rhaj.,1 ,,l I l.i- I i^. horn in Ireland, but eame to this .ui.il rli .i'i li W,',l.i,.,.l,v .'.i'i MAIN STREET CHATHAM I'lninuy when young. She has bem PROPERTY IS ON SUMMIT AV! a resident of Chatham for man TOCK TWO FROM ORANGE A. A. •„',IM ih. II >i IUI'IL i- •cars, and was a member of St. Pai- .•I II. l,. I ,1 -..-ll A re il c.-i'ii'i' .leal of largo iironor ilel.'s f'hnrrli. The fune'al service; Ihe loeal bowlers enlfiiati • ! th• |. -

Sheila Never Go As Fast As You Would Wish!) Don’T Worry – We Will Let You Know When You Can Open That Present!

Bear in Mind An electronic newsletter from Bear Threads Ltd. Volume 4 – Issue 1 January 2012 From The Editor – I hope you will enjoy this newsletter. In it there is lots of information that I think you will find helpful for the 2012! coming months and beyond. And I am looking forward to showing you all that is new at the Creative Sewing Market in Birmingham. Remember the dates are January 15‐16. Seems only yesterday we were turning the calendar to the new millennium of 2000! Indeed this is a new year and an Till Birmingham, Happy Stitching – exciting one as well, for Bear Threads. * We will soon be inaugurating a new website (things Sheila never go as fast as you would wish!) Don’t worry – we will let you know when you can open that present! *I will begin teaching again with several informative as well as fun lectures and projects. There are classes for beginner to advanced, as well as shop owners, too. BIRMINGHAM CREATIVE SEWING Please call for more information. MARKET *We have many new fabrics to entice your spring sewing. Sunday and Monday Honestly there are too many new fabrics to list here, but January 15 and 16, 2012 for teasers, we have brought back the beautiful Ecru in the Marriot Hotel – Hwy. 280 just south of I‐459 Bearissima. AND we have brought back the TRUE LAWN, in white, pink and blue. *We have a new price list that is easier to read and it lists Be sure to see Bear Threads, Ltd. first. -

Books for Daily Life: Household, Husbandry, Behaviour 514 13

THE CAMBRIDGE DICTION ARIUM SAXONICO-LA TINO .ANGLICUM. History of the Book in Britain +++++++ A,,!:DlCI)IUm initW., helper ben:; behop~. Nil .f- i edic ...., denunrio"" procbma- +"""C::nonnW"Iuanl olio- r){.. q.iJnup ... tft).'q.ifq•• , re,publiarc. to publi1I1, to ;3 X &+fum, tOque:per a- "..;tj",e,p;s;1fJ;,.~.r);'_tiftHf"1 p~oclaime. Ill: abannan. c .. +~ ~t phzrcf.. A.,li, ufi.. ptr p.. if ........ pi'.I<,./IT. Hoc dicto cOnyoc.rc, congn:gorc; +++++++1iIIi1limuu bOdic&- lin&'1i Danica :mer., I. V. evoarc. to call fOltb, ftIrn. po przcifum. E. G. W..... : Liur"/IT~ Rnie" c· ·mOIl, eOllilU!lal~ 01 call to- abzpan, to bUn: alx:ot>an, ..,. p. 160. grtbtr. 'T.llttniciftidou fig- to bib: abpecan, to· bjtake, Xa.:. qucrcus, robur. an l!I>ake. nific:Ltion.,.!c ab eodan font., VOLUME IV I< oIi. fexcen ... At~i hoc ip- lingua Danid v... ee cik. Wor~ banntn: barbu~, b, ••iTt. (um .x ufu 8< gano linguz .,illS. Kili_. ClIke, !ce. V. Hinc ctiam nollraaum bAnne., GN/I:Z ad A.~III detintum. a.:.. prO nupOuwn I"'ctO publica- 1557-1695 quod. intcr oIia. plUt.1 . haud ~ . ~em.s, ilrucs, p>:ra, to. Hue infuper ( quod ad 0- ",.1!;tria, me doc~t Slu~Orum I.gm. cong~n ... mgu.,. R.!!,IIt, rigincm alliDct) tcfercndum mc"rum &'utnr ille UDICU" D. a iIllIOob>ptle. BtJ. HdUi. ~. e. G2I10ruri'l . b.".ir. /talorum Mtricll" C.{... ""'. rna,:ru I.. b.nJir•• oollradum banni1l1. 'I'llidem patti, non minor fill- Xalte p.p. IgniariullI. a girr- i. profcriberc; in exilium~; ..s, at d. -

Testing the Baseline Hypothesis in South Korea

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Rudolf, Robert; Kang, Sung-Jin Working Paper Adaptation under Traditional Gender Roles: Testing the Baseline Hypothesis in South Korea Discussion Papers, No. 101 Provided in Cooperation with: Courant Research Centre 'Poverty, Equity and Growth in Developing and Transition Countries', University of Göttingen Suggested Citation: Rudolf, Robert; Kang, Sung-Jin (2011) : Adaptation under Traditional Gender Roles: Testing the Baseline Hypothesis in South Korea, Discussion Papers, No. 101, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Courant Research Centre - Poverty, Equity and Growth (CRC-PEG), Göttingen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/90495 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Courant Research Centre ‘Poverty, Equity and Growth in Developing and Transition Countries: Statistical Methods and Empirical Analysis’ Georg-August-Universität Göttingen (founded in 1737) Discussion Papers No. -

Fine Golf Books from the Library of Duncan Campbell and Other Owners

Sale 461 Thursday, August 25, 2011 11:00 AM Fine Golf Books from the Library of Duncan Campbell and Other Owners Auction Preview Tuesday, August 23, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, August 24, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, August 25, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/ realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www. pbagalleries.com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. -

Australian Superfine Wool Growers Association Inc

AustrAliAn superfine Wool Growers’ Association inc. AustrAliAn superfine Wool Growers Association inc. AnnuAl 2015-2016 www.aswga.com 1 | Annual 2015/2016 Australian Wool Innovation On-farm tools for woolgrowers Get involved in key initiatives such as: • Join an AWI-funded Lifetime Ewe Management group to lift production - www.wool.com/ltem • Join your state’s AWI extension network - www.wool.com/networks • Benchmark your genetic progress with MERINOSELECT - www.wool.com/merinoselect • Reducing wild dog predation through coordinated action - www.wool.com/wilddogs • Training shearers and woolhandlers - www.wool.com/shearertraining • Enhanced worm control through planning - www.wool.com/wormboss • Getting up to scratch with lice control - www.wool.com/lice • Flystrike protection and prevention - www.wool.com/fl ystrike VR2224295 www.wool.com | AWI Helpline 1800 070 099 Disclaimer: Whilst Australian Wool Innovation Limited and its employees, offi cers and contractors and any contributor to this material (“us” or “we”) have used reasonable efforts to ensure that the information contained in this material is correct and current at the time of its publication, it is your responsibility to confi rm its accuracy, reliability, suitability, currency and completeness for use for your purposes. To the extent permitted by law, we exclude all conditions, warranties, guarantees, terms and obligations expressed, implied or imposed by law or otherwise relating to the information contained in this material or your use of it and will have no liability to you, however arising and under any cause of action or theory of liability, in respect of any loss or damage (including indirect, special or consequential loss or damage, loss of profi t or loss of business opportunity), arising out of or in connection with this material or your use of it. -

Squanto's Garden

© 2006 Bill Heid Contents An Introduction to Squanto’s Garden...4 Chapter One ...6 Squanto and the Pilgrims:...6 Squanto’s History ...7 The First Meeting...12 Squanto and the Pilgrims...14 The First Thanksgiving...15 Chapter Two...18 The Soil Then...18 The Geological History of Plymouth...18 The Land Before the Pilgrims...19 The Land of New Plymouth...21 Chapter Three...23 Why Did Squanto’s Methods Work?...23 Tastes Better, Is Better...25 Chapter Four...28 The Soil Today and What It Produces...28 Chapter Five...31 Squanto’s Garden Today...31 Assessing Your Soil and Developing a Plan...31 What to Grow...34 Garden Design...35 Wampanoag...36 Wampanoag...37 Hidatsa Gardens...38 Hidasta...39 Zuni Waffle Garden...40 Zuni Waffle Garden...41 Caring for Your Garden...42 Recipes...43 Conclusion-Squanto’s Legacy...49 Resources...51 An Introduction to Squanto’s Garden When the Pilgrims first came to America, they nearly starved because of insufficient food. It was with the help of a Native American they knew as Squanto that they learned to properly cultivate the land so that they could survive and flourish. All of that might seem quite removed from your own gardening endeavors, however there is much to be learned from those historical lessons. What was the soil like then? How did the soil affect the food being grown? What techniques were used to enrich the soil? Why is it that the Pilgrims, being from a more technologically advanced society, needed the help of the Native Americans to survive? Whether you are an experienced gardener, or just starting out, “Squanto’s Garden” has plenty to teach you. -

Division of Domestic Labour and Lowest-Low Fertility in South Korea

DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 37, ARTICLE 24, PAGES 743-768 PUBLISHED 26 SEPTEMBER 2017 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol37/24/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.24 Research Article Division of domestic labour and lowest-low fertility in South Korea Erin Hye-Won Kim This publication is part of the Special Collection on “Domestic Division of Labour and Fertility Choice in East Asia,” organized by Guest Editors Ekaterina Hertog and Man-Yee Kan. © 2017 Erin Hye-Won Kim This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 2.0 Germany, which permits use, reproduction, and distribution in any medium for noncommercial purposes, provided the original author(s) and source are given credit. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/de/ Contents 1 Introduction 744 2 Current knowledge and gaps in the literature 745 2.1 Husbands’ contribution 745 2.2 Help from parents and parents-in-law 746 2.3 Formal childcare 747 3 The Korean context 748 4 Data, variables, and the research design 749 4.1 Data 749 4.2 Fertility intentions and fertility behaviour 750 4.3 Division of domestic labour 750 4.4 Regression analysis of fertility intentions and behaviour on help 751 with domestic labour 5 Results 753 5.1 Description of fertility intentions and fertility behaviour 753 5.2 Women’s domestic labour, informal and formal help received, and 755 related factors 5.3 Regression analysis of fertility on help with domestic labour 757 6 Conclusion 760 7 Acknowledgements 763 References 764 Demographic Research: Volume 37, Article 24 Research Article Division of domestic labour and lowest-low fertility in South Korea Erin Hye-Won Kim1 Abstract BACKGROUND One explanation offered for very low fertility has been the gap between improvements in women’s socioeconomic status outside the home and gender inequality in the home. -

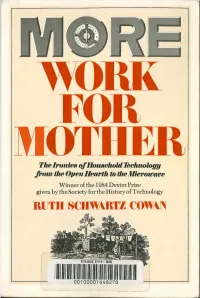

More Work for Mother

The It--onies ofHousehohl'JeehnowgiJ ft--om the Open Heat--th to the Miet--owave Winner of the 1984 Dexter Prize given by the Society for the History of Technology -RUTH SCHWARTZ COWAN ETHICS ETH·- BIB II II 111111 II II II llllllllllllll II 00100001648270 More Work for Mother MORE WORK FOR MOTHER The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave Ruth Schwartz Cowan • BasicBooks- A Division of HarperCollinsPub/ishen Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cowan, Ruth Schwartz, 1941- More work for mother. Bibliography: p. 220 Includes index. 1. Horne economics-United States-History. 2. Household appliances-United States-History. 3. Housewives-United States-History I. Title. II. Title: Household technology from the open hearth to the microwave. TX23.C64 1983 640'.973 83-70759 ISBN 0-465-04731-9 (cloth) ISBN 0-465-04732-7 (paper) Copyright © 1983 by Basic Books, Inc. Printed in the United States of America Designed by Vincent Torre 10 9 8 7 For Betty Schwartz and Louis E. Schwartz with love Contents PICTURE ESSAYS ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS XI Chapter 1 An Introduction: Housework and Its Tools 3 Chapter 2 Housewifery: Household Work and Household Tools under Pre-Industrial Conditions 16 Housewifery and the Doctrine of Separate Spheres 18 Household Tools and Household Work 20 The Household Division of Labor 26 The Household and the Market Economy 31 Conclusion 3 7 Chapter 3 The Invention of Housework: The Early Stages of Industrialization 40 Milling Flour and Making Bread 46 The Evolution of the Stove 53 More Chores -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The qualify of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pag%, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each orignal is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. EGgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infoniiation C o m p aiy 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor MI 4S106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 RAPE AND THE RHETORIC OF FEMALE CHASTITY IN ENGLISH RENAISSANCE LITERATURE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nancy Weitz Miller, B.A., M.A., M.A.