Notes from East Berlin: a Coming to Terms with the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Escape to Freedom: a Story of One Teenager’S Attempt to Get Across the Berlin Wall

Escape to Freedom: A story of one teenager’s attempt to get across the Berlin Wall By Kristin Lewis From the April 2019 SCOPE Issue Every muscle in Hartmut Richter’s body ached. He’d been in the cold water for four agonizing hours. His body temperature had plummeted dangerously low. Now, to his horror, he found himself trapped in the water by a wall of razor-sharp barbed wire. Precious seconds ticked by. The area was crawling with guards carrying machine guns. Some had snarling dogs at their sides. If they caught Hartmut, he could be thrown in prison—or worse. These men were trained to shoot on sight. Hartmut grabbed the wire with his bare hands. He began pulling it apart, hoping he could make a hole large enough to squeeze through. Hartmut Richter was not a criminal escaping from jail. He was not a bank robber on the run. He was simply an 18-year-old kid who wanted nothing more than to be free—to listen to the music he wanted to listen to, to say what he wanted to say and think what he wanted to think. And right now, Hartmut was risking everything to escape from his country and start a new life. A Bleak Time Hartmut was born in Germany in 1948. He lived near the capital city of Berlin with his parents and younger sister. This was a bleak time for his country. Only three years earlier, Germany had been defeated in World War II. During the war, Germany had invaded nearly every other country in Europe. -

Tageszeitung (Taz) Article on the Opening of the Berlin Wall

Volume 10. One Germany in Europe, 1989 – 2009 The Fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9, 1989) Two journalists from Die Tageszeitung (taz), a left-of-center West Berlin newspaper, describe the excitement generated by the sudden opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989. The event was the result of internal pressure applied by East German citizens, and it evoked spontaneous celebration from a people who could once again freely cross the border and rekindle relationships with friends and relatives on the other side. (Please note: the dancing bear mentioned below is a figurative reference to West Berlin's official mascot. Beginning in 1954, the flag of West Berlin featured a red bear set against a white background. In 1990, the bear became the mascot of a unified Berlin. The former West Berlin flag now represents the city as a whole.) "We Want In!" The Bear Is Dancing on the Border Around midnight, RIAS – the American radio station broadcasting to the East – still has no traffic interruptions to report. Yet total chaos already reigns at the border checkpoint on Invalidenstrasse. People parked their cars at all conceivable angles, jumped out, and ran to the border. The transmission tower of the radio station "Free Berlin" is already engulfed by a throng of people (from the West) – waiting for the masses (from the East) to break through. After three seconds, even the most hardened taz editor finds himself applauding the first Trabi he sees. Everyone gets caught up in the frenzy, whether she wants to or not. Even the soberest members of the crowd are applauding, shrieking, gasping, giggling. -

DEFA Directors and Their Criticism of the Berlin Wall

«Das ist die Mauer, die quer durchgeht. Dahinter liegt die Stadt und das Glück.» DEFA Directors and their Criticism of the Berlin Wall SEBASTIAN HEIDUSCHKE MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY This article examines the strategies used by directors of the East German film monopoly Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft (DEFA) to voice their disap- proval of the Berlin Wall.1 My aim is to show how it was possible, despite universal censorship in East Germany, to create films that addressed the wall as an inhumane means to imprison the East German people. Although many DEFA films adhered to socialist law and reiterated the official doctrine of the «antifascist protection rampart» on the silver screen, an analysis of three DEFA films will demonstrate how the representation of human crisis was used as a means to criticize the wall.2 The films Das Kleid (Konrad Petzold, 1961), Der geteilte Himmel (Konrad Wolf, 1964), and Die Architekten (Peter Kahane, 1990) address walls in a variety of functions and appearances as rep- resentations, symbols, and metaphors of the barrier between East and West Germany. Interest in DEFA has certainly increased during the last decade, and many scholars have introduced a meaningful variety of topics regarding the history of East Germany’s film company and its films. In addition to book-length works that deal exclusively with the cinema of East Germany, many articles have looked at DEFA’s film genres, provided case studies of single DEFA films, and engaged in sociological or historical analyses of East German so- ciety and its films.3 In order to expand the current discussion of DEFA, this article applies a sociocultural reading to the three DEFA films Das Kleid, Der geteilte Himmel, and Die Architekten with the goal of introducing the new subtopic of roles and functions of the Berlin Wall in East German film to the field of DEFA studies. -

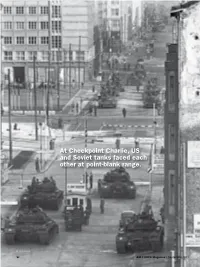

At Checkpoint Charlie, US and Soviet Tanks Faced Each Other at Point-Blank Range

At Checkpoint Charlie, US and Soviet tanks faced each other at point-blank range. AP Ppoto/Kreusch 92 AIR FORCE Magazine / September 2011 Showdown in BerlinBy John T. Correll any place was ground zero for the The First Crisis from the 1948 confrontation—Walter Cold War, it was Berlin. The first Berlin crisis was in 1948, Ulbricht, the Communist Party boss in Awash in intrigue, the former when the Soviets and East Germans East Germany. capital of the Third Reich lay 110 attempted to cut the city off from the Ulbricht, handpicked for the job by miles inside the Iron Curtain but outside world. However, three air the Soviet Premier, Joseph Stalin, was was not part of East Germany. corridors into Berlin, each 20 miles charmless, intense, and dogmatic, but IEach of the four victorious powers in wide, remained open. The Americans a good administrator and a reliable en- Europe in World War II—the United and British responded with the Berlin forcer of Soviet hegemony. Stalin had States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Airlift, which sustained West Berlin visions of a unified Germany as part Union—held control of a sector of the with food, fuel, and other supplies from of the Soviet sphere of influence, but city, which would be preserved as the June 1948 to September 1949. Ulbricht had so antagonized the popu- future capital of a reunified Germany. Some senior officials in the US De- lace the Communists had no chance of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev partment of State had favored abandon- winning free elections. called it “the most dangerous place in the ing Berlin. -

Building of the Berlin Wall

BUILDING OF THE BERLIN WALL a A CITY TORN APART b A CITY TORN APART OF BUILDING THE BERLIN WALL in conjunction with a symposium given on 27 OCTOBER 2011 at the NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, DC WASHINGTON, DC RECORDS ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND at the 27 OCTOBER 2011 in conjunction with a symposium given on BUILDING BERLIN WALL OF ITY TORN APART A C BUILDING OF THE BERLIN WALL brandenburg gate Built in 1791, standing 85 feet high, 215 feet long and 36 feet wide, this former city gate is one of the most iconic symbols of Berlin and Germany. Throughout its existence it has served as a visual representation of various political ideologies, ranging from Prussia’s imperialism to East Germany’s communism. It was closed by the East Germans on 14 August 1961 in a response to West Berliners’ demonstration against the building of the wall dividing their city into East and West. It remained closed until 22 December 1989. Its design is based upon the gate way to the Propylaea, the entry into the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. It has 12 Doric columns, six to a side, forming five passageways. The central archway is crowned by the Quadriga, a statue consisting of a four horse chariot driven by Victoria, the Roman goddess of victory. After Napoleon’s defeat, the Quadriga was returned to Berlin and the wreath of oak leaves on Victoria was replaced with the new symbol of Prussia, the Iron Cross. i A CITYC ITY TORNTO RN APART a family divided A couple from Berlin may never see each other again because they became separated by the newly formed Berlin Wall. -

Designed by Professor Misty Sabol | 7 Days | June 2017

Designed by Professor Misty Sabol | 7 Days | June 2017 College Study Tour s BERLIN: THE CITY EXPERIENCE INCLUDED ON TOUR Round-trip flights on major carriers; Full-time Tour Director; Air-conditioned motorcoaches and internal transportation; Superior tourist-class hotels with private bathrooms; Breakfast daily; Select meals with a mix of local cuisine. Sightseeing: Berlin Alternative Berlin Guided Walking Tour Entrances: Business Visit KW Institute for Contemporary Art Berlinische Galerie (Museum of Modern Art) Topography of Terror Museum 3-Day Museum Pass BMW Motorcycle Plant Tour Reichstag Jewish Holocaust Memorial Overnight Stays: Berlin (5) NOT INCLUDED ON TOUR Optional excursions; Insurance coverage; Beverages and lunches (unless otherwise noted); Transportation to free-time activities; Customary gratuities (for your Tour Director, bus driver and local guide); Porterage; Adult supplement (if applicable); Weekend supplement; Shore excursion on cruises; Any applicable baggage-handing fee imposed by the airlines SIGN UP TODAY (see efcollegestudytours.com/baggage for details); Expenses caused by airline rescheduling, cancellations or delays caused by the airlines, bad efcst.com/1868186WR weather or events beyond EF’s control; Passports, visa and reciprocity fees YOUR ITINERARY Day 1: Board Your Overnight Flight to Berlin! Day 4: Berlin Day 2: Berlin Visit a Local Business Berlin's outstanding infrastructure and highly qualified and educated Arrive in Berlin workforce make it a competitive location for business. Today you will Arrive in historic Berlin, once again the German capital. For many visit a local business. (Please note this visit is pending confirmation years the city was defined by the wall that separated its residents. In and will be confirmed closer to departure.) the last decade, since the monumental events that ended Communist rule in the East, Berlin has once again emerged as a treasure of arts Receive a 3 Day Museum Pass and architecture with a vibrant heart. -

Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989

The Berlin Wall was the 97-mile-long physical barrier that separated the city of West Berlin from East Berlin and the rest of East Germany from 1961 until the East German government relaxed border controls in November 1989. The 13-foot-high concrete wall snaked through Berlin, effectively sealing off West Berlin from ground access except for through heavily guarded checkpoints. It included guard towers and a wide area known as the “death strip” that contained anti-vehicle trenches, barbed wire, and other defenses. The wall came to symbolize the “Iron Curtain” that separated Western Europe and the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. As East Germany grew more socialist in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, about 3.5 million East Germans fled from East Berlin into democratic West Berlin. From there, they could then travel to West Germany and other Western European countries. It became clear to the powers of East Germany that they might not survive as a state with open borders to the West. Between 1961 and 1989, the wall prevented almost all such emigration. Among the many attempt to escape included through underground tunnels, hot-air balloons, and with the support of organized groups of Fluchthelfer (flight helpers). The East German border guards’ shoot-to-kill order against refugees resulted in about 250-300 deaths between August 1961, and February 1989. Demonstrations and protests in the late 1980’s began to build stress on the East German government to open the city. In the summer of 1989, neighboring Hungary opened its border and thousands of East Germans fled the communist country for the West. -

Behind the Berlin Wall.Pdf

BEHIND THE BERLIN WALL This page intentionally left blank Behind the Berlin Wall East Germany and the Frontiers of Power PATRICK MAJOR 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York Patrick Major 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Major, Patrick. -

Berlin Visit Focus Berlinhistory

BERLIN / EAST BERLIN HISTORY Berlin House of Representatives (Abgeordnetenhaus) Niederkirchnerstraße 5, 10117 Berlin Contact: +49 (0) 30 23250 Internet: https://www.parlament-berlin.de/de/English The Berlin House of Representatives stands near the site of the former Berlin Wall, and today finds itself in the center of the reunified city. The president directs and coordinates the work of the House of Representatives, assisted by the presidium and the Council of Elders, which he or she chairs. Together with the Martin Gropius Bau, the Topography of Terror, and the Bundesrat, it presents an arresting contrast to the flair of the new Potsdamer Platz. (source: https://www.parlament-berlin.de/de/English) FHXB Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg museum Adalbertstraße 95A, 10999 Berlin Contact: +49 (0)30 50 58 52 33 Internet: https://www.fhxb-museum.de The intricate web of different experiences of history, lifestyles, and ways of life; the coexistence of different cultures and nationalities in tight spaces; contradictions and fissures: These elements make the Berlin district of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg compelling – and not only to those interested in history. The Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Museum documents the history of this district. It emerged from the fusion of the districts of Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg with the merger of the Kreuzberg Museum with the Heimatmuseum Friedrichshain. In 1978, the Kreuzberg Office for the Arts began to develop a new type of local museum, in which everyday history – a seemingly banal relic – and the larger significance -

MAUERRESTE Ln Berlln RELICTS of the BERLIN WALL

Gerhard Sälter MAUERRESTE IN BERLIN RELICTS OF THE BERLIN WALL Der Abbau der Berliner Mauer und noch sichtbare Reste in der Berliner Innenstadt The Dismantling of the Berlin Wall and the Visible Remains in the Berlin City Center Zweite, überarbeitete Auflage Translated by Miriamne Fields Based on the 2nd revised edition Herausgegeben vom Verein Berliner Mauer Gedenkstätte und Dokumentationszentrum e.V. Berlin 2007 INHALT 4 Das Ende der Berliner Mauer The end of the Berlin wall 10 Abriss der Mauer Tearing Down the Wall 18 Verbleib der Relikte What Happened to the Wall Relicts 24 In Berlin noch sichtbare Reste der Mauer Locating Relicts of the Wall in Berlin Impressum Herausgeber/Publisher 42 Literaturhinweise Verein Berliner Mauer – Gedenkstätte und Dokumentationszentrum Bibiliography Redaktion/Editor Maria Nooke, Lydia Dollmann 43 Anmerkungen Notes Fotonachweis/Photo credits S. 5: Landesarchiv Berlin (1989) S. 13: Rainer Just (1990) S. 16, 21, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, Umschlag: Yvonne Kavermann (2004) S. 37: Brigitte Hiss (2004) Gestaltung/Design gewerk design, Berlin Druck Druckerei Elsholz, Berlin Berlin 2007 ISBN 3-00-014780-2 2 3 DAS ENDE DER BERLINER MAUER THE END OF THE BERLIN WALL Die Berliner Mauer hat das Stadt bild zwi - The Wall had a major impact on Berlin’s schen 1961 und 1989 wesentlich geprägt. Sie war wie die Befestigung urban landscape from 1961 to 1989. Like the fortification of the border bet- und Absicherung der innerdeutschen Grenze ein wesentliches Instru- ween West Germany and the GDR, it was an instrument to stabilize the East ment der Herrschaftssicherung in der DDR, indem sie die Freizügig- German government’s power by effectively restricting the population’s free- keit der Bevölkerung wirksam unterband.1 Darüber hinaus symbo lisiert dom of movement.1 sie heute wie damals den Charakter des SED-Regimes und wurde nach Today, it continues to characterize the nature of the SED (the ruling com- 1989 zu einem Symbol für die überwundene Teilung Berlins, Deutsch- munist party in the GDR) regime. -

50 Jahre Ministerkonferenz Für Raumordnung (MKRO)

50 Jahre Ministerkonferenz für Raumordnung Festschrift anlässlich des 50-jährigen Bestehens der MKRO www.bmvi.de Diese Broschüre greift einzelne Themen heraus, die besonders anschaulich einen Überblick über den Wandel der Raumordnung von 1967 bis heute geben. Über den QR-Code am Ende eines Textes gelangen Sie zu weiterführenden Informationen zum jeweiligen Thema, mit umfangreichem Kartenmaterial, Texten aus den Raumord- nungsberichten und Beschlüssen der MKRO. Und so geht’s: QR-Code Scanner auf Ihrem Smartphone oder Tablet als App herunterladen, das Kameraauge zum Scannen auf das Symbol halten - Sie werden automatisch zu den weiterführenden Inhalten geleitet. Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort ...............................................................................................................................2 Mobilität .............................................................................................................................4 Umweltschutz ...................................................................................................................6 Urbanisierung ....................................................................................................................8 Raumordnung 1967-1977 ............................................................................................ 10 Raumordnung 1977-1987 ............................................................................................ 14 Raumordnung 1987-1997 ........................................................................................... -

Heinrich Bortfeldt Interviews

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4199r6np No online items Register of the Heinrich Bortfeldt Interviews Finding aid prepared by Hoover Institution Library and Archives Staff Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2010 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Heinrich Bortfeldt 2002C60 1 Interviews Title: Heinrich Bortfeldt interviews Date (inclusive): 2001-2006 Collection Number: 2002C60 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: German Physical Description: 3 manuscript boxes, 3 oversize boxes(2.4 Linear Feet) Abstract: Sound recordings and transcripts of interviews of leaders of the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands and of the Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus, and of other German political and cultural figures, relating to political conditions in East Germany and in reunified Germany. Creator: Bortfeldt, Heinrich Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 2002. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Heinrich Bortfeldt interviews, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Scope and Content of Collection The Heinrich Bortfeldt Collection consists of several series of oral history interviews conducted by Bortfeldt, a German historian, between 2001 and 2006. These interviews were a follow-up to an earlier series of interviews conducted in the former East Germany during the period of transition following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and German reunification in 1990.