Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Escape to Freedom: a Story of One Teenager’S Attempt to Get Across the Berlin Wall

Escape to Freedom: A story of one teenager’s attempt to get across the Berlin Wall By Kristin Lewis From the April 2019 SCOPE Issue Every muscle in Hartmut Richter’s body ached. He’d been in the cold water for four agonizing hours. His body temperature had plummeted dangerously low. Now, to his horror, he found himself trapped in the water by a wall of razor-sharp barbed wire. Precious seconds ticked by. The area was crawling with guards carrying machine guns. Some had snarling dogs at their sides. If they caught Hartmut, he could be thrown in prison—or worse. These men were trained to shoot on sight. Hartmut grabbed the wire with his bare hands. He began pulling it apart, hoping he could make a hole large enough to squeeze through. Hartmut Richter was not a criminal escaping from jail. He was not a bank robber on the run. He was simply an 18-year-old kid who wanted nothing more than to be free—to listen to the music he wanted to listen to, to say what he wanted to say and think what he wanted to think. And right now, Hartmut was risking everything to escape from his country and start a new life. A Bleak Time Hartmut was born in Germany in 1948. He lived near the capital city of Berlin with his parents and younger sister. This was a bleak time for his country. Only three years earlier, Germany had been defeated in World War II. During the war, Germany had invaded nearly every other country in Europe. -

Endless House: Intersections of Art and Architecture June 27, 2015–March 6, 2016 the Robert Menschel Architecture and Design Gallery, Third Floor

Endless House: Intersections of Art and Architecture June 27, 2015–March 6, 2016 The Robert Menschel Architecture and Design Gallery, third floor Endless House considers the single-family home and archetypes of dwelling as a theme for the creative endeavors of architects and artists. Through drawings, photographs, video, installations, and architectural models drawn from MoMA’s collection, the exhibition highlights how artists have used the house as a means to explore universal topics, and how architects have tackled the design of residences to expand their discipline in new ways. The exhibition also marks the 50th anniversary of the death of Viennese-born artist and architect Frederick Kiesler (1890–1965). Taking its name from an unrealized project by Kiesler, Endless House celebrates his legacy and the cross-pollination of art and architecture that made Kiesler’s 15-year project a reference point for generations to come. Work by architects and artists spanning more than seven decades are exhibited alongside materials from Kiesler’s Endless House design and images of its presentation in MoMA’s 1960 Visionary Architecture exhibition. Intriguing house designs—ranging from historical projects by Mies van der Rohe, Frank Gehry, Peter Eisenman, and Rem Koolhaas, to new acquisitions from Smiljan Radic and Asymptote Architecture—are juxtaposed with visions from artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Bruce Nauman, Mario Merz, and Rachel Whiteread. Together these works demonstrate how the dwelling occupies a central place in a cultural exchange across generations and disciplines. Organized by Pedro Gadanho, Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art Architecture and Design Collection Exhibitions are made possible by Hyundai Card and Hyundai Capital America. -

Tageszeitung (Taz) Article on the Opening of the Berlin Wall

Volume 10. One Germany in Europe, 1989 – 2009 The Fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9, 1989) Two journalists from Die Tageszeitung (taz), a left-of-center West Berlin newspaper, describe the excitement generated by the sudden opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989. The event was the result of internal pressure applied by East German citizens, and it evoked spontaneous celebration from a people who could once again freely cross the border and rekindle relationships with friends and relatives on the other side. (Please note: the dancing bear mentioned below is a figurative reference to West Berlin's official mascot. Beginning in 1954, the flag of West Berlin featured a red bear set against a white background. In 1990, the bear became the mascot of a unified Berlin. The former West Berlin flag now represents the city as a whole.) "We Want In!" The Bear Is Dancing on the Border Around midnight, RIAS – the American radio station broadcasting to the East – still has no traffic interruptions to report. Yet total chaos already reigns at the border checkpoint on Invalidenstrasse. People parked their cars at all conceivable angles, jumped out, and ran to the border. The transmission tower of the radio station "Free Berlin" is already engulfed by a throng of people (from the West) – waiting for the masses (from the East) to break through. After three seconds, even the most hardened taz editor finds himself applauding the first Trabi he sees. Everyone gets caught up in the frenzy, whether she wants to or not. Even the soberest members of the crowd are applauding, shrieking, gasping, giggling. -

Nowe Miasto Pod Ziemią New Underground City

EWA WĘCŁAWOWICZ-GYURKOVICH∗ NOWE MIASTO POD ZIEMIĄ NEW UNDERGROUND CITY Streszczenie Obserwowana na przełomie wieków fascynacja formami organicznymi, zakrzywionymi bądź pofałdowanymi zmusza do sięgania do świata przyrody, by odkrywać ją niejako na nowo. Szeroki kontekst środowiska, pejzaż, większe fragmenty natury nie zaskakują w analizie projektowej. Nie przypadkiem znowu powracamy do obecnej w awangardzie od lat 70. Sztuki Ziemi. Różnorodność bazująca na topografii terenu staje się podstawową wytyczną wszelkich działań. Słowa kluczowe: miasto, architektura współczesna Abstract Fascination with organic, bent, or undulating forms, observable at the turn of centuries, calls for reference to the world of nature to discover it once again. Broad context of the environment, landscape, bigger fragments of nature do not surprise in design analysis. It is not accidental that we return to the Art of Earth, present in avant-garde since the 70s. Variety basing on topography of the site becomes the guideline of all activity. Keywords: city, contemporary architecture ∗ Dr inż. arch. Ewa Węcławowicz-Gyurkovich, Instytut Historii Architektury i Konserwacji Zabytków, Wydział Architektury, Politechnika Krakowska. 196 (...) z miastami jest jak ze snami: wszystko co wyobrażalne może się przyśnić, ale nawet najbardziej zaskakujący sen jest rebusem, który kryje w sobie pragnienie lub jego odwrotną stronę – lęk. Miasta jak sny są zbudowane z pragnień i lęków, nawet jeśli wątek ich mowy jest utajony, zasady – absurdalne, perspektywy – złudne, a każda rzecz kryje w sobie inną (...) Italo Calvino, Niewidzialne miasta1 Nowe Centrum Kulturalne prowincji Galicja w zachodnio-północnej Hiszpanii zajmuje całe wzgó- rze na zachodnim pogórzu Gór Kantabryjskich, na przedmieściach miasta Santiago de Compostela. Region Galicji od X w. p.n.e. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

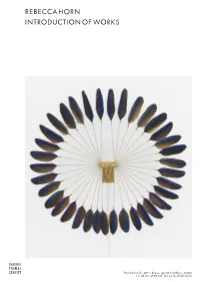

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

DEFA Directors and Their Criticism of the Berlin Wall

«Das ist die Mauer, die quer durchgeht. Dahinter liegt die Stadt und das Glück.» DEFA Directors and their Criticism of the Berlin Wall SEBASTIAN HEIDUSCHKE MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY This article examines the strategies used by directors of the East German film monopoly Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft (DEFA) to voice their disap- proval of the Berlin Wall.1 My aim is to show how it was possible, despite universal censorship in East Germany, to create films that addressed the wall as an inhumane means to imprison the East German people. Although many DEFA films adhered to socialist law and reiterated the official doctrine of the «antifascist protection rampart» on the silver screen, an analysis of three DEFA films will demonstrate how the representation of human crisis was used as a means to criticize the wall.2 The films Das Kleid (Konrad Petzold, 1961), Der geteilte Himmel (Konrad Wolf, 1964), and Die Architekten (Peter Kahane, 1990) address walls in a variety of functions and appearances as rep- resentations, symbols, and metaphors of the barrier between East and West Germany. Interest in DEFA has certainly increased during the last decade, and many scholars have introduced a meaningful variety of topics regarding the history of East Germany’s film company and its films. In addition to book-length works that deal exclusively with the cinema of East Germany, many articles have looked at DEFA’s film genres, provided case studies of single DEFA films, and engaged in sociological or historical analyses of East German so- ciety and its films.3 In order to expand the current discussion of DEFA, this article applies a sociocultural reading to the three DEFA films Das Kleid, Der geteilte Himmel, and Die Architekten with the goal of introducing the new subtopic of roles and functions of the Berlin Wall in East German film to the field of DEFA studies. -

At Checkpoint Charlie, US and Soviet Tanks Faced Each Other at Point-Blank Range

At Checkpoint Charlie, US and Soviet tanks faced each other at point-blank range. AP Ppoto/Kreusch 92 AIR FORCE Magazine / September 2011 Showdown in BerlinBy John T. Correll any place was ground zero for the The First Crisis from the 1948 confrontation—Walter Cold War, it was Berlin. The first Berlin crisis was in 1948, Ulbricht, the Communist Party boss in Awash in intrigue, the former when the Soviets and East Germans East Germany. capital of the Third Reich lay 110 attempted to cut the city off from the Ulbricht, handpicked for the job by miles inside the Iron Curtain but outside world. However, three air the Soviet Premier, Joseph Stalin, was was not part of East Germany. corridors into Berlin, each 20 miles charmless, intense, and dogmatic, but IEach of the four victorious powers in wide, remained open. The Americans a good administrator and a reliable en- Europe in World War II—the United and British responded with the Berlin forcer of Soviet hegemony. Stalin had States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Airlift, which sustained West Berlin visions of a unified Germany as part Union—held control of a sector of the with food, fuel, and other supplies from of the Soviet sphere of influence, but city, which would be preserved as the June 1948 to September 1949. Ulbricht had so antagonized the popu- future capital of a reunified Germany. Some senior officials in the US De- lace the Communists had no chance of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev partment of State had favored abandon- winning free elections. called it “the most dangerous place in the ing Berlin. -

Building of the Berlin Wall

BUILDING OF THE BERLIN WALL a A CITY TORN APART b A CITY TORN APART OF BUILDING THE BERLIN WALL in conjunction with a symposium given on 27 OCTOBER 2011 at the NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, DC WASHINGTON, DC RECORDS ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND at the 27 OCTOBER 2011 in conjunction with a symposium given on BUILDING BERLIN WALL OF ITY TORN APART A C BUILDING OF THE BERLIN WALL brandenburg gate Built in 1791, standing 85 feet high, 215 feet long and 36 feet wide, this former city gate is one of the most iconic symbols of Berlin and Germany. Throughout its existence it has served as a visual representation of various political ideologies, ranging from Prussia’s imperialism to East Germany’s communism. It was closed by the East Germans on 14 August 1961 in a response to West Berliners’ demonstration against the building of the wall dividing their city into East and West. It remained closed until 22 December 1989. Its design is based upon the gate way to the Propylaea, the entry into the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. It has 12 Doric columns, six to a side, forming five passageways. The central archway is crowned by the Quadriga, a statue consisting of a four horse chariot driven by Victoria, the Roman goddess of victory. After Napoleon’s defeat, the Quadriga was returned to Berlin and the wreath of oak leaves on Victoria was replaced with the new symbol of Prussia, the Iron Cross. i A CITYC ITY TORNTO RN APART a family divided A couple from Berlin may never see each other again because they became separated by the newly formed Berlin Wall. -

Designed by Professor Misty Sabol | 7 Days | June 2017

Designed by Professor Misty Sabol | 7 Days | June 2017 College Study Tour s BERLIN: THE CITY EXPERIENCE INCLUDED ON TOUR Round-trip flights on major carriers; Full-time Tour Director; Air-conditioned motorcoaches and internal transportation; Superior tourist-class hotels with private bathrooms; Breakfast daily; Select meals with a mix of local cuisine. Sightseeing: Berlin Alternative Berlin Guided Walking Tour Entrances: Business Visit KW Institute for Contemporary Art Berlinische Galerie (Museum of Modern Art) Topography of Terror Museum 3-Day Museum Pass BMW Motorcycle Plant Tour Reichstag Jewish Holocaust Memorial Overnight Stays: Berlin (5) NOT INCLUDED ON TOUR Optional excursions; Insurance coverage; Beverages and lunches (unless otherwise noted); Transportation to free-time activities; Customary gratuities (for your Tour Director, bus driver and local guide); Porterage; Adult supplement (if applicable); Weekend supplement; Shore excursion on cruises; Any applicable baggage-handing fee imposed by the airlines SIGN UP TODAY (see efcollegestudytours.com/baggage for details); Expenses caused by airline rescheduling, cancellations or delays caused by the airlines, bad efcst.com/1868186WR weather or events beyond EF’s control; Passports, visa and reciprocity fees YOUR ITINERARY Day 1: Board Your Overnight Flight to Berlin! Day 4: Berlin Day 2: Berlin Visit a Local Business Berlin's outstanding infrastructure and highly qualified and educated Arrive in Berlin workforce make it a competitive location for business. Today you will Arrive in historic Berlin, once again the German capital. For many visit a local business. (Please note this visit is pending confirmation years the city was defined by the wall that separated its residents. In and will be confirmed closer to departure.) the last decade, since the monumental events that ended Communist rule in the East, Berlin has once again emerged as a treasure of arts Receive a 3 Day Museum Pass and architecture with a vibrant heart. -

Arc De La Villette Competition Entry, 1982, Original Image Cropped

OMA, Parc de la Villette competition entry, 1982, original image cropped, http://oma.eu/projects/parcdelavillette ARC 201: Design Studio 3: Process, Process, Process SYLLABUS FALL 2018 CREDITS 6 CLASS HOURS MWF 1:00 pm – 4:20 pm 1 2018 ARC201 Syllabus INSTRUCTORS Mustafa Faruki mustafa@thelablab.com Crosby 120 Julia Jamrozik (coordinator) [email protected] Crosby 101 Virginia Melnyk [email protected] Crosby 110 Nellie Niespodzinski [email protected] Crosby 160 Sasson Rafailov [email protected] Crosby 130 Jon Spielman [email protected] Crosby 150 ELIGIBILITY ARC102: Architectural Design Studio. Architecture majors only. PREREQUISITES/COREQUISITES ARC311: Architectural Media 3 required. ARC 241: Environmental Systems – recommended. These courses will be linked in content and schedule. COURSE DESCRIPTION How do we design? What drives ideas and what generates concepts? How do we productively and critically engage with the vast history and contemporary practice of architecture in the process? How do we design places that are rooted in their location but reflective of the past and aspiring to a better future? How do we meld idealism with practicality? This studio will not offer answers to all of these questions but it will introduce one methodology and prompt a selfconscious and introspective approach to the design process. The studio is guided by ideas of morphology and context. Morphology is understood as formfinding or the deliberate, logical and wellargumented development of a formal strategy. Context is understood as the relation to site at different scales and through different lenses (physical, social, cultural) and includes the history of the discipline of architecture. -

Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989

The Berlin Wall was the 97-mile-long physical barrier that separated the city of West Berlin from East Berlin and the rest of East Germany from 1961 until the East German government relaxed border controls in November 1989. The 13-foot-high concrete wall snaked through Berlin, effectively sealing off West Berlin from ground access except for through heavily guarded checkpoints. It included guard towers and a wide area known as the “death strip” that contained anti-vehicle trenches, barbed wire, and other defenses. The wall came to symbolize the “Iron Curtain” that separated Western Europe and the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. As East Germany grew more socialist in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, about 3.5 million East Germans fled from East Berlin into democratic West Berlin. From there, they could then travel to West Germany and other Western European countries. It became clear to the powers of East Germany that they might not survive as a state with open borders to the West. Between 1961 and 1989, the wall prevented almost all such emigration. Among the many attempt to escape included through underground tunnels, hot-air balloons, and with the support of organized groups of Fluchthelfer (flight helpers). The East German border guards’ shoot-to-kill order against refugees resulted in about 250-300 deaths between August 1961, and February 1989. Demonstrations and protests in the late 1980’s began to build stress on the East German government to open the city. In the summer of 1989, neighboring Hungary opened its border and thousands of East Germans fled the communist country for the West.