Historic Approaches to Sonic Encounter at the Berlin Wall Memorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archbishop Says Berlin Wall Was a Good Friday in German History

Archbishop says Berlin Wall was a Good Friday in German history BERLIN (CNS) — Catholics and Protestants gathered Aug. 13 to remember the day in 1961 when their city was divided, becoming a symbol of the Cold War. Catholic Archbishop Heiner Koch joined his Protestant counterpart, Bishop Christian Stäblein, for an ecumenical prayer service in the Chapel of Reconciliation, on the spot where part of the wall was built. Today, a few wall remnants still remain in a remembrance garden. Archbishop Koch reminded those gathered in the small chapel that without Good Friday, there would not have been a Resurrection on Easter. “Today we remember one of the Good Fridays in the history of Berlin and Germany. We have gathered at one of the many Golgotha mounds in our city and our country, directly at a monument that for many of us was a symbol of bondage and confinement, and which reminds us today of the preciousness of freedom,” he said. Archbishop Koch remembered how, as a young boy, he was on vacation with his parents in Italy when the wall went up. He recalled the anger and powerlessness of his parents and other adults as they watched, in disbelief, the images on television. It was his mother’s birthday, but no one was celebrating. Early on that Sunday morning in 1961, the Soviet sector border was sealed off when more than 10,000 East German security forces started to tear up the pavement in Berlin; they erected barricades and barbed wire fences. A few days later, the concrete slabs that would become the wall started to go up. -

After the Berlin Wall Hope M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04931-4 — After the Berlin Wall Hope M. Harrison Frontmatter More Information AFTER THE BERLIN WALL The history and meaning of the Berlin Wall remain controversial, even three decades after its fall. Drawing on an extensive range of archival sources and interviews, this book profiles key memory activists who have fought to commemorate the history of the Berlin Wall and examines their role in the creation of a new German national narrative. With victims, perpetrators, and heroes, the Berlin Wall has joined the Holocaust as an essential part of German collective memory. Key Wall anniversaries have become signposts marking German views of the past, its relevance to the present, and the complicated project of defining German national iden- tity. Considering multiple German approaches to remembering the Wall via memorials, trials, public ceremonies, films, and music, this revelatory work also traces how global memory of the Wall has impacted German memory policy. It depicts the power and fragility of state-backed memory projects, and the potential of such projects to reconcile or divide. hope m. harrison is Associate Professor of History and International Affairs at the George Washington University. The recipient of fellowships from Fulbright, the Wilson Center, and the American Academy in Berlin, she is the author of Driving the Soviets up the Wall (2003), which was awarded the 2004 Marshall Shulman Book Prize by the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies, and was also published to wide acclaim in German translation. She has served on the National Security Council staff, currently serves on the board of three institutions in Berlin connected to the Cold War and the Berlin Wall, and has appeared on CNN, the History Channel, the BBC, and Deutschlandradio. -

Berlin by Sustainable Transport

WWW.GERMAN-SUSTAINABLE-MOBILITY.DE Discover Berlin by Sustainable Transport THE SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT GUIDE GERMANY The German Partnership for Sustainable Mobility (GPSM) The German Partnership for Sustainable Mobility (GPSM) serves as a guide for sustainable mobility and green logistics solutions from Germany. As a platform for exchanging knowledge, expertise and experiences, GPSM supports the transformation towards sustainability worldwide. It serves as a network of information from academia, businesses, civil society and associations. The GPSM supports the implementation of sustainable mobility and green logistics solutions in a comprehensive manner. In cooperation with various stakeholders from economic, scientific and societal backgrounds, the broad range of possible concepts, measures and technologies in the transport sector can be explored and prepared for implementation. The GPSM is a reliable and inspiring network that offers access to expert knowledge, as well as networking formats. The GPSM is comprised of more than 150 reputable stakeholders in Germany. The GPSM is part of Germany’s aspiration to be a trailblazer in progressive climate policy, and in follow-up to the Rio+20 process, to lead other international forums on sustainable development as well as in European integration. Integrity and respect are core principles of our partnership values and mission. The transferability of concepts and ideas hinges upon respecting local and regional diversity, skillsets and experien- ces, as well as acknowledging their unique constraints. www.german-sustainable-mobility.de Discover Berlin by Sustainable Transport This guide to Berlin’s intermodal transportation system leads you from the main train station to the transport hub of Alexanderplatz, to the redeveloped Potsdamer Platz with its high-qua- lity architecture before ending the tour in the trendy borough of Kreuzberg. -

Escape to Freedom: a Story of One Teenager’S Attempt to Get Across the Berlin Wall

Escape to Freedom: A story of one teenager’s attempt to get across the Berlin Wall By Kristin Lewis From the April 2019 SCOPE Issue Every muscle in Hartmut Richter’s body ached. He’d been in the cold water for four agonizing hours. His body temperature had plummeted dangerously low. Now, to his horror, he found himself trapped in the water by a wall of razor-sharp barbed wire. Precious seconds ticked by. The area was crawling with guards carrying machine guns. Some had snarling dogs at their sides. If they caught Hartmut, he could be thrown in prison—or worse. These men were trained to shoot on sight. Hartmut grabbed the wire with his bare hands. He began pulling it apart, hoping he could make a hole large enough to squeeze through. Hartmut Richter was not a criminal escaping from jail. He was not a bank robber on the run. He was simply an 18-year-old kid who wanted nothing more than to be free—to listen to the music he wanted to listen to, to say what he wanted to say and think what he wanted to think. And right now, Hartmut was risking everything to escape from his country and start a new life. A Bleak Time Hartmut was born in Germany in 1948. He lived near the capital city of Berlin with his parents and younger sister. This was a bleak time for his country. Only three years earlier, Germany had been defeated in World War II. During the war, Germany had invaded nearly every other country in Europe. -

He Big “Mitte-Struggle” Politics and Aesthetics of Berlin's Post

Martin Gegner he big “mitt e-struggl e” politics and a esth etics of t b rlin’s post-r nification e eu urbanism proj ects Abstract There is hardly a metropolis found in Europe or elsewhere where the 104 urban structure and architectural face changed as often, or dramatically, as in 20 th century Berlin. During this century, the city served as the state capital for five different political systems, suffered partial destruction pós- during World War II, and experienced physical separation by the Berlin wall for 28 years. Shortly after the reunification of Germany in 1989, Berlin was designated the capital of the unified country. This triggered massive building activity for federal ministries and other governmental facilities, the majority of which was carried out in the old city center (Mitte) . It was here that previous regimes of various ideologies had built their major architectural state representations; from to the authoritarian Empire (1871-1918) to authoritarian socialism in the German Democratic Republic (1949-89). All of these époques still have remains concentrated in the Mitte district, but it is not only with governmental buildings that Berlin and its Mitte transformed drastically in the last 20 years; there were also cultural, commercial, and industrial projects and, of course, apartment buildings which were designed and completed. With all of these reasons for construction, the question arose of what to do with the old buildings and how to build the new. From 1991 onwards, the Berlin urbanism authority worked out guidelines which set aesthetic guidelines for all construction activity. The 1999 Planwerk Innenstadt (City Center Master Plan) itself was based on a Leitbild (overall concept) from the 1980s called “Critical Reconstruction of a European City.” Many critics, architects, and theorists called it a prohibitive construction doctrine that, to a certain extent, represented conservative or even reactionary political tendencies in unified Germany. -

Tageszeitung (Taz) Article on the Opening of the Berlin Wall

Volume 10. One Germany in Europe, 1989 – 2009 The Fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9, 1989) Two journalists from Die Tageszeitung (taz), a left-of-center West Berlin newspaper, describe the excitement generated by the sudden opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989. The event was the result of internal pressure applied by East German citizens, and it evoked spontaneous celebration from a people who could once again freely cross the border and rekindle relationships with friends and relatives on the other side. (Please note: the dancing bear mentioned below is a figurative reference to West Berlin's official mascot. Beginning in 1954, the flag of West Berlin featured a red bear set against a white background. In 1990, the bear became the mascot of a unified Berlin. The former West Berlin flag now represents the city as a whole.) "We Want In!" The Bear Is Dancing on the Border Around midnight, RIAS – the American radio station broadcasting to the East – still has no traffic interruptions to report. Yet total chaos already reigns at the border checkpoint on Invalidenstrasse. People parked their cars at all conceivable angles, jumped out, and ran to the border. The transmission tower of the radio station "Free Berlin" is already engulfed by a throng of people (from the West) – waiting for the masses (from the East) to break through. After three seconds, even the most hardened taz editor finds himself applauding the first Trabi he sees. Everyone gets caught up in the frenzy, whether she wants to or not. Even the soberest members of the crowd are applauding, shrieking, gasping, giggling. -

Miller, Schwaag, Warner the New Death Strip Blaster of Architecture № ① 1.MMXI

Miller, Schwaag, Warner The New Death Strip blaster of architecture THE HEURIS GONZO BLURBANISM T IC JOURNAL FOR № ① THE 1.MMXI NEW DEATH StRIP THE NEW DEATH StRIP MIller, Schwaag, Warner SLAB Magazine The Heuristic Journal for Gonzo Blurbanism Imprint Content Published by: Arno Brandlhuber, Silvan Linden akademie c/o Architektur und Stadtforschung, Forward 4 AdBK Nürnberg Method 6 Editors: Oliver Miller, Daniel Schwaag, Ian Warner Re-Coding the Environs 8 All photos: the authors Rewe + Aldi =Rewaldi 18 Layout: Blotto Design, Berlin Europarc.de 20 Typefaces: Vectora, News Gothic, LiSong Kernel Memory Dump 28 Cover photo: Traffic police filming motorists on A Future Squat 30 the A113 in south east Berlin Color Plates 33 Printed by: Druckerei zu Altenburg Distribution: www.vice-versa-vertrieb.de La Dolcé Ignoranza! 49 © Publishers and authors, Hashing out the Grey Zone 56 Nürnberg / Berlin, January 2011 Landscape Rules: The Lessons of A113 60 Free Form 68 Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der National bibliografie; Hyperbolic Seam 69 detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet Striptonwickburgshirehamwaldetinow 72 abrufbar. Postscript: For Unreal 76 http://dnb.ddb.de List of Projects / Bibliography 78 ISSN 1862-1562 The Authors / Slab Magazine 79 ISBN 978-3-940092-04-5 fied Berlin, land that very quickly became prime real estate once the geopolitical FORWARD map of the Cold War was trashed in ’89. OlIver MIller The concern of this study, however, is to look elsewhere: to the forlorn corners of the death strip in 2010. To be sure, this is not the death strip from ten, twenty or thirty years ago. -

ANNIVERSARY ND of AUGUST 1945 Th ALPI Magazine

ALPI magazine 7 | 2015 th ANNIVERSARY SINCE THE 2ND OF AUGUST 1945 ASSOCIAZIONE ITALIANA CONTRO L’EPILESSIA alpiworld.com SEZ. REGIONE TOSCANA ONLUS Alpi Magazine 07 Art Work Gerecon Italia © Albini&Pitigliani March 2015 ANNIVERSARY th 2015 is a special year for all of us at Albini & Pitigliani. ALPI It was 70 years ago, on August 2, 1945, when my father and Mr. NORD-EST2 Pitigliani established the Company in Prato, a textile center near Florence. BECOFRANCE Initially the Company handled domestic traffic mostly for the south of 4 Italy; then, in conjunction with the economic boom of the 1950’s, the I Company grew quickly and developed European and overseas traffic. ALBINI&PITIGLIANI NAPLES 6 In order to offer our customers a very accurate service, the Company BIG made joint ventures in Europe, the United States, and Asia to reach the FIVE present dimensions of 60 associated companies and a staff of about DUBAI 1500 people. ALPI 10 N WORLDWIDE Our grateful thoughts go to the Founders and to Fabrizio Pitigliani, who CONVENTION have been the engine for such development. 2014 12 ALPI BEST PARTNER Together with my brother Nando, I support the third generation, who LONDON TEXTILE FAIR are very concerned about continuing the families’ traditions, not only in PREMIÈRE VISION PARIS terms of feelings and mutual friendship, but also in terms of remarkable 18 developments and success. D ALPI EASY They face difficult times and big changes in a world full of contradictions, COOKING23 but they seem ready to hand over the message of the past generations ALPI to the fourth one, who, by looking at photos (see pag.12) seem to be BEST PARTNER getting ready! PREMIÈRE VISION PARIS 24 On behalf of the Board, I want to thank all our past and present employees E ALPI and associates around the world, and above all, our customers who BERLIN NEWS have trusted us with their business and have enabled us to achieve 26 our goals. -

Heinrich Zille's Berlin Selected Themes from 1900

"/v9 6a~ts1 HEINRICH ZILLE'S BERLIN SELECTED THEMES FROM 1900 TO 1914: THE TRIUMPH OF 'ART FROM THE GUTTER' THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Catherine Simke Nordstrom Denton, Texas May, 1985 Copyright by Catherine Simke Nordstrom 1985 Nordstrom, Catherine Simke, Heinrich Zille's Berlin Selected Themes from 1900 to 1914: The Trium of 'Art from the Gutter.' Master of Arts (Art History), May, 1985, 139 pp., 71 illustrations, bibliography, 64 titles. Heinrich Zille (1858-1929), an artist whose creative vision was concentrated on Berlin's working class, portrayed urban life with devastating accuracy and earthy humor. His direct and often crude rendering linked his drawings and prints with other artists who avoided sentimentality and idealization in their works. In fact, Zille first exhibited with the Berlin Secession in 1901, only months after Kaiser Wilhelm II denounced such art as Rinnsteinkunst, or 'art from the gutter.' Zille chose such themes as the resultant effects of over-crowded, unhealthy living conditions, the dissolution of the family, loss of personal dignity and economic exploi tation endured by the working class. But Zille also showed their entertainments, their diversions, their excesses. In so doing, Zille laid bare the grim and the droll realities of urban life, perceived with a steady, unflinching gaze. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . S S S . vi CHRONOLOGY . xi Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 5 . 1 II. AN OVERVIEW: BERLIN, ART AND ZILLE . 8 III. "ART FROM THE GUTTER:" ZILLE'S THEMATIC CHOICES . -

DEFA Directors and Their Criticism of the Berlin Wall

«Das ist die Mauer, die quer durchgeht. Dahinter liegt die Stadt und das Glück.» DEFA Directors and their Criticism of the Berlin Wall SEBASTIAN HEIDUSCHKE MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY This article examines the strategies used by directors of the East German film monopoly Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft (DEFA) to voice their disap- proval of the Berlin Wall.1 My aim is to show how it was possible, despite universal censorship in East Germany, to create films that addressed the wall as an inhumane means to imprison the East German people. Although many DEFA films adhered to socialist law and reiterated the official doctrine of the «antifascist protection rampart» on the silver screen, an analysis of three DEFA films will demonstrate how the representation of human crisis was used as a means to criticize the wall.2 The films Das Kleid (Konrad Petzold, 1961), Der geteilte Himmel (Konrad Wolf, 1964), and Die Architekten (Peter Kahane, 1990) address walls in a variety of functions and appearances as rep- resentations, symbols, and metaphors of the barrier between East and West Germany. Interest in DEFA has certainly increased during the last decade, and many scholars have introduced a meaningful variety of topics regarding the history of East Germany’s film company and its films. In addition to book-length works that deal exclusively with the cinema of East Germany, many articles have looked at DEFA’s film genres, provided case studies of single DEFA films, and engaged in sociological or historical analyses of East German so- ciety and its films.3 In order to expand the current discussion of DEFA, this article applies a sociocultural reading to the three DEFA films Das Kleid, Der geteilte Himmel, and Die Architekten with the goal of introducing the new subtopic of roles and functions of the Berlin Wall in East German film to the field of DEFA studies. -

Traditional Materials Optimized for the Twenty-First Century

T RADITIONAL MATERIALS OPTIMIZED for THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY ELIZABETH GOLDEN University of Washington INTRODUCTION been few organizations and manufacturers willing to invest in the testing and promotion of traditional materials. Consequently, their The rapid pace of development and economic forces have contrib- predictability hardly improved before the 1990s, and traditional con- uted to the ever increasing complexity of construction, with most struction methods remained relatively unaffected by technological building components being manufactured from materials and miner- advances in the construction industry. In the mid-1990s, however, als extracted from locations thousands of miles from the sites where many traditional materials saw a strong revival in several countries they are installed. In their article, Global in a Not-so-Global World, due to growing concerns about climate change, higher demands for Mark Jarzombek and Alfred Hwangbo observe that “Buildings of even healthier, nontoxic building materials and a newfound desire to re- humble proportions are today a composite of materials from probably connect with local culture through indigenous materials. Currently, a dozen or more different countries. In that sense, buildings are far a small but growing number of architects and engineers around the more foundational as a map of global realities...than even a shoe.”1 world are critically reexamining traditional building materials and The current state of architectural affairs is that buildings are less an finding fertile ground for innovation. Material research and testing, in expression of place, and more an assembled product, created by sup- addition to collaborative onsite training, are providing architects with ply chain logistics and industrial manufacturing processes. -

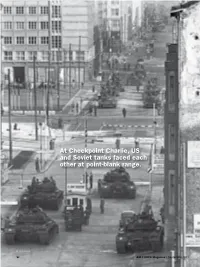

At Checkpoint Charlie, US and Soviet Tanks Faced Each Other at Point-Blank Range

At Checkpoint Charlie, US and Soviet tanks faced each other at point-blank range. AP Ppoto/Kreusch 92 AIR FORCE Magazine / September 2011 Showdown in BerlinBy John T. Correll any place was ground zero for the The First Crisis from the 1948 confrontation—Walter Cold War, it was Berlin. The first Berlin crisis was in 1948, Ulbricht, the Communist Party boss in Awash in intrigue, the former when the Soviets and East Germans East Germany. capital of the Third Reich lay 110 attempted to cut the city off from the Ulbricht, handpicked for the job by miles inside the Iron Curtain but outside world. However, three air the Soviet Premier, Joseph Stalin, was was not part of East Germany. corridors into Berlin, each 20 miles charmless, intense, and dogmatic, but IEach of the four victorious powers in wide, remained open. The Americans a good administrator and a reliable en- Europe in World War II—the United and British responded with the Berlin forcer of Soviet hegemony. Stalin had States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Airlift, which sustained West Berlin visions of a unified Germany as part Union—held control of a sector of the with food, fuel, and other supplies from of the Soviet sphere of influence, but city, which would be preserved as the June 1948 to September 1949. Ulbricht had so antagonized the popu- future capital of a reunified Germany. Some senior officials in the US De- lace the Communists had no chance of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev partment of State had favored abandon- winning free elections. called it “the most dangerous place in the ing Berlin.