Arab TV-Audiences: Negotiating Religion and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read the Full PDF

en Books published to date in the continuing series o .:: -m -I J> SOVIET ADVANCES IN THE MIDDLE EAST, George Lenczowski, 1971. 176 C pages, $4.00 ;; Explores and analyzes recent Soviet policies in the Middle East in terms of their historical background, ideological foundations and pragmatic application in the 2 political, economic and military sectors. n PRIVATE ENTERPRISE AND SOCIALISM IN THE MIDDLE EAST, Howard S. Ellis, m 1970. 123 pages, $3.00 en Summarizes recent economic developments in the Middle East. Discusses the 2- significance of Soviet economic relations with countries in the area and suggests new approaches for American economic assistance. -I :::I: TRADE PATTERNS IN THE MIDDLE EAST, Lee E. Preston in association with m Karim A. Nashashibi, 1970. 93 pages, $3.00 3: Analyzes trade flows within the Middle East and between that area and other areas of the world. Describes special trade relationships between individual -C Middle Eastern countries and certain others, such as Lebanon-France, U.S .S.R. C Egypt, and U.S.-Israel. r m THE DILEMMA OF ISRAEL, Harry B. Ellis, 1970. 107 pages, $3.00 m Traces the history of modern Israel. Analyzes Israel 's internal political, eco J> nomic, and social structure and its relationships with the Arabs, the United en Nations, and the United States. -I JERUSALEM: KEYSTONE OF AN ARAB-ISRAELI SETTLEMENT, Richard H. Pfaff, 1969. 54 pages, $2.00 Suggests and analyzes seven policy choices for the United States. Discusses the religious significance of Jerusalem to Christians, Jews, and Moslems, and points out the cultural gulf between the Arabs of the Old City and the Western r oriented Israelis of West Jerusalem. -

ISIS Success in Iraq: a Movement 40 Years in the Making Lindsay Church a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirem

ISIS Success in Iraq: A Movement 40 Years in the Making Lindsay Church A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN INTERNATIONAL STUDIES: MIDDLE EAST University of Washington 2016 Committee: Terri DeYoung Arbella Bet-Shlimon Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies !1 ©Copyright 2016 Lindsay Church !2 University of Washington Abstract ISIS Success in Iraq: A Movement 40 Years in the Making Lindsay Church Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Terri DeYoung, Near Eastern Language and Civilization In June 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS)1 took the world by surprise when they began forcibly taking control of large swaths of territory in Iraq and Syria. Since then, policy makers, intelligence agencies, media, and academics have been scrambling to find ways to combat the momentum that ISIS has gained in their quest to establish an Islamic State in the Middle East. This paper will examine ISIS and its ability to build an army and enlist the support of native Iraqis who have joined their fight, or at the very least, refrained from resisting their occupation in many Iraqi cities and provinces. In order to understand ISIS, it is imperative that the history of Iraq be examined to show that the rise of the militant group is not solely a result of contemporary problems; rather, it is a movement that is nearly 40 years in the making. This thesis examines Iraqi history from 1968 to present to find the historical cleavages that ISIS exploited to succeed in taking and maintaining control of territory in Iraq. -

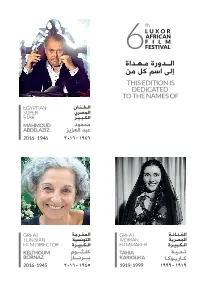

ﺍﻝــﺛﻭﺭﺓ ﻄـﻋـﺛﺍﺓ ﺇﻝﻯ ﺍﺠﻃ ﺾﻀ ﻄﻆ This Edition Is Dedicated to the Names Of

th LUXOR AFRICAN FILM 6FESTIVAL ﺍﻝــﺛﻭﺭﺓ ﻄـﻋـﺛﺍﺓ ﺇﻝﻯ ﺍﺠﻃ ﺾﻀ ﻄﻆ THIS EDITION IS DEDICATED TO THE NAMES OF ﺍﻝـﻑـﻈـﺍﻥ EGYPTIAN ﺍﻝﻡﺧﺭﻱ SUPER ﺍﻝﺿـﺊـﻐـﺭ STAR ﻄﺗﻡﻌﺩ MAHMOUD ﺲﺊﺛ ﺍﻝﺳﺞﻏﺞ ABDELAZIZ ١٩٤٦ - ٢٠١٦ 1946 - 2016 ﺍﻝﻑـﻈـﺍﻇـﺋ GREAT ﺍﻝﻡﺚـﺭﺝﺋ GREAT ﺍﻝﻡﺧﺭﻏﺋ IVORIAN ﺍﻝﺎﻌﻇﺱﻐﺋ TUNISIAN ﺍﻝـﺿـﺊﻐـﺭﺓ FILMMAKER ﺍﻝـﺿـﺊﻐـﺭﺓ FILM DIRECTOR ﺕـﺗـﻐـﺋ TAHIA ﺾﻂـﺑـــﻌﻡ KELTHOUM ﺾـﺍﺭﻏـﻌﺾـﺍ KARIOUKA ﺏـــﺭﻇـــﺍﺯ BORNAZ ١٩١٩ - ١٩٩٩ 1999 1919- ١٩٤٥ - ٢٠١٦ -1945 2016 ﺖﻂﻡﻎ ﺍﻝﻈﻡﻈﻃ ﻭﺯﻏﺭ ﺍﻝﺑﺼﺍﺸﺋ MINISTER OF CULTURE HELMY AL NAMNAM ﺗﺄﺗﻲ اﻟﺪورة اﻟﺴﺎدﺳﺔ ﻟﻬﺬا اﻟﻤﻬﺮﺟﺎن، ﻓﻲ ﻇﻞ ﻣﻨﻌﻄﻒ ﺟﺪﻳﺪ، إﻳﺠﺎﺑﻲ وﻣﻬﻢ، ﺗﺸﻬﺪه ﻣﺼﺮ، ﺣﻴﺚ ﺻﺎر اﻻﻫﺘﻤﺎم ﺑﺎﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎ -ﻋﻤﻮﻣ -ﻣﻦ أوﻟﻮﻳﺎت اﻟﺤﻜﻮﻣﺔ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ، ارﺗﻔﻌﺖ اﻟﻤﻴﺰاﻧﻴﺔ اﻟﻤﺨﺼﺼﺔ ﻟﺼﻨﺪوق دﻋﻢ اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎ، ﻣﻦ ٢٠ ﻣﻠﻴﻮن ﺟﻨﻴﺔ إﻟﻰ ٥٠ ﻣﻠﻴﻮن ﺟﻨﻴﺔ ﺳﻨﻮﻳ، وﻳﺠﺮي اﻟﻌﻤﻞ ﺑﺠﺪﻳﺔ ﻟﺘﺄﺳﻴﺲ اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎﺗﻴﻚ، وﺗﺄﺳﻴﺲ ﺷﺮﻛﺔ ﻗﺎﺑﻀﺔ ﻟﻧﺘﺎج اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎﺋﻲ، ﻣﻤﺎ ٌﻳﺒﺸﺮ ﺑﺈزدﻫﺎر ﺣﻘﻴﻘﻲ ﻟﺼﻨﺎﻋﺔ اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎ، وﻓﻀﻼً ﻋﻦ ذﻟﻚ، ﻓﺈن ا¨ﻧﺘﺎج اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎﺋﻲ اﻟﻤﺼﺮي، ﺷﻬﺪ ﺧﻼل اﻟﻌﺎم اﻟﻤﻨﺼﺮم ارﺗﻔﺎﻋ ﻓﻲ أﻋﺪاد ا³ﻓﻼم اﻟﺘﻲ ﺗﻢ إﻧﺘﺎﺟﻬﺎ، وﺗﻤﻴﺰ· ﻓﻲ اﻟﻤﺴﺘﻮى اﻟﻔﻨﻲ. ﺗﺄﺗﻲ ﻫﺬه اﻟﺪورة -ﻛﺬﻟﻚ -ﻓﻲ ﻇﻞ اﻫﺘﻤﺎم اﻟﺪوﻟﺔ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ ﺑﺘﻨﺸﻴﻂ وﺗﻌﻤﻴﻖ اﻟﻌﻼﻗﺎت اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ -ا³ﻓﺮﻳﻘﻴﺔ، ودﻋﺎ اﻟﺮﺋﻴﺲ ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻔﺘﺎح اﻟﺴﻴﺴﻲ ﻓﻲ ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ ﻣﺆﺗﻤﺮ أﺳﻮان ﻟﻠﺸﺒﺎب، إﻟﻰ إﻋﺪاد أﺳﻮان ﻟﺘﻜﻮن ﻋﺎﺻﻤﺔ ﻟﻗﺘﺼﺎد واﻟﺜﻘﺎﻓﺔ ا¨ﻓﺮﻳﻘﻴﺔ. وأﺧﻴﺮ·، ﺗﺘﻮاﻓﻖ ﻫﺬه اﻟﺪورة ﻣﻦ اﻟﻤﻬﺮﺟﺎن، ﻣﻊ اﻻﺣﺘﻔﺎل ﺑﺎ³ﻗﺼﺮ ﻋﺎﺻﻤﺔ ﻟﻠﺜﻘﺎﻓﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ، ﻃﻮال ﻫﺬا اﻟﻌﺎم، ﻛﺎﻧﺖ ا³ﻗﺼﺮ داﺋﻤ ﻧﻘﻄﺔ اﻟﺘﻘﺎء ﺑﻴﻦ اﻟﺤﻀﺎرﺗﻴﻦ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ اﻟﻘﺪﻳﻤﺔ (اﻟﻔﺮﻋﻮﻧﻴﺔ) واﻟﺤﻀﺎرة اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ – ا¨ﺳﻼﻣﻴﺔ، واﺧﺘﻴﺎر ا³ﻗﺼﺮ ﻋﺎﺻﻤﺔ ﻟﻠﺜﻘﺎﻓﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ، ﻳﺆﻛﺪ ﻋﻠﻰ ﻫﺬا ٌاﻟﺒﻌﺪ. The sixth edition of Luxor African Film Festival comes within the shadow of a new positive and significant turn that Egypt is witnessing of paying a special attention to cinema and being one of the priorities of the Egyptian government as the budget of the cinema fund has increased from 20 million EGP to 50 million EGP annually, while tireless efforts are made to found Cimatheque and founding a company for cinema production that promises a rich cinema production in addition to the increase of the number of produced films last year and of a good quality. -

10. Alfilm 10

10. ALFILM 3. — 10.4.2019 Berlin Filmfestival Arabisches فهرس Inhalt Content جدول العروض 6 Programmübersicht Program overview اإلختيارات الرسمية 11 OFFICIAL SELECTION برامج خاصة 30 Win a Co-Production! SPECIALS القاعات والبطاقات 35 Eintrittspreise und Film Prize of the Robert Bosch Stiftung for International Cooperation Spielorte Venues and tickets Germany / Arab World الداعمون والشركاء 38 Partner und Each year, the Robert Bosch Stiftung issues three Film Prizes for International Förderer Supporters and partners Cooperation to teams of emerging filmmakers from Germany and the Arab world. The prizes, each worth 60,000 euros, are awarded for realising a joint film project in the categories short animation, short fiction, and short or feature length documentary. The call for entries opens every May. Deadline for the 2020 Film Prize submissions is July 31, 2019. Apply at www.filmprize.de Kritisch. Mutig. Meinungsstark. Stay tuned on www.facebook.com/FilmPrize Testen Sie den Freitag! Die unabhängige Wochenzeitung für Politik, Kultur und Wirtschaft. Jetzt Wochen lang kostenlos lesen! “Four Acts for Syria”, 2019 by Waref Abu Quba and Kevork Mourad Robuste Tasche mit langen Henkeln aus Bio-Baumwolle. Der ideale Alltags-Begleiter in Dunkelblau www.freitag.de/lesen 4 5 ترحيب Grußwort Greetings Liebe Freunde, Dear friends, بسعادة وفخر، ننظر إلى عشر سنوات مضت على مهرجان الفيلم العربي برلين. منذ خطوات انطالقنا األولى في عام ٢٠٠٩، وضعنا mit Stolz und Freude schauen wir auf nun it is with pride and joy that we look نصب أعيننا مهمة إيصال الفن السينمائي العربي، قصصه wunder- back on 10 years of ALFILM. What ein für Was zurück. -

![Mossad [The Greatest Missions of the Israeli Secret Service].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9406/mossad-the-greatest-missions-of-the-israeli-secret-service-pdf-6279406.webp)

Mossad [The Greatest Missions of the Israeli Secret Service].Pdf

MOSSAD THE GREATEST MISSIONS OF THE ISRAELI SECRET SERVICE MICHAEL BAR-ZOHAR AND NISSIM MISHAL Dedications For heroes unsung For battles untold For books unwritten For secrets unspoken And for a dream of peace never abandoned, never forgotten —Michael Bar-Zohar To Amy Korman For her advice, her inspiration, and her being my pillar of support —Nissim Mishal Contents Dedications Introduction - Alone, in the Lion’s Den Chapter One - King of Shadows Chapter Two - Funerals in Tehran Chapter Three - A Hanging in Baghdad Chapter Four - A Soviet Mole and a Body at Sea Chapter Five - “Oh, That? It’s Khrushchev’s Speech . .” Chapter Six - “Bring Eichmann Dead or Alive!” Chapter Seven - Where Is Yossele? Chapter Eight - A Nazi Hero at the Service of the Mossad Chapter Nine - Our Man in Damascus Chapter Ten - “I Want a MiG-21!” Chapter Eleven - Those Who’ll Never Forget Chapter Twelve - The Quest for the Red Prince Chapter Thirteen - The Syrian Virgins Chapter Fourteen - “Today We’ll Be at War!” Chapter Fifteen - A Honey Trap for the Atom Spy Photo Section Chapter Sixteen - Saddam’s Supergun Chapter Seventeen - Fiasco in Amman Chapter Eighteen - From North Korea with Love Chapter Nineteen - Love and Death in the Afternoon Chapter Twenty - The Cameras Were Rolling Chapter Twenty-one - From the Land of the Queen of Sheba Epilogue - War with Iran? Acknowledgments Bibliography and Sources Index About the Authors Copyright About the Publisher Introduction Alone, in the Lion’s Den On November 12, 2011, a tremendous explosion destroyed a secret missile base close to Tehran, killing seventeen Revolutionary Guards and reducing dozens of missiles to a heap of charred iron. -

An Introductory Survey of the Plays, Novels, and Stories of Tawfiq Al-Hakim, As Translated Into English

AN INTRODUCTORY SURVEY OF THE PLAYS, NOVELS, AND STORIES OF TAWFIQ AL-HAKIM, AS TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH A THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in The Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christina M. Sidebottom, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Thomas Postlewait, Adviser ~qo~ Dr. Joseph Zeidan Advisor Adviser, Department of Theatre ABSTRACT This thesis will provide an introductory survey of the plays, novels, short stories and other writing of Tawfiq al-Hakim, which have been translated into English. This work will be useful to English-speaking readers who are interested in learning more about Tawfiq al-Hakim and his literary works. The study will include a brief biography of al-Hakim together with an overview of the political regimes, geographical conditions, and the socio- economic environment that had an impact on the various phases of al-Hakim's life. An analysis of examples of significant publications spanning al-Hakim's writing career will be undertaken. The main focus of this thesis will be an discussion of the play F ate o f a Cockroach, in particular Act One which could be read as a political allegory for the life and times of Gamal Abdul Nasir, the military conflicts during his political regime, and the rise and fall of the United Arab Republic (1958-1961). The discussion will include a synopsis of the play, a description of the characters, and a literary analysis of the play, explaining the political allegory. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere thanks go to my advisor, Dr. -

A Political Economy of Egyptian Foreign Policy: State, Ideology, and Modernisation Since 1970

London School of Economics A Political Economy of Egyptian Foreign Policy: State, Ideology, and Modernisation since 1970 Yasser Mohamed Elwy MOHAMED MAHMOUD A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, April 2009. UMI Number: U615702 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615702 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F iz-vssvv A Political Economy o f Egyptian Foreien Policy: State. Ideology and Modernisation since 1970 Yasser M. Elwv Declaration I certify that this thesis, presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science, is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. -

Negotiating Religion and Identity of Reference

Galal (ed.) Galal (ed.) Ehab Galal (ed.) Ehab Galal (ed.) Arab TV-Audiences Today the relations between Arab audiences and Arab media are characterised by plural- ism and fragmentation. More than a thousand Arab satellite TV channels alongside oth- er new media platforms are offering all kinds of programming. Religion has also found a Arab TV-Audiences vital place as a topic in mainstream media or in one of the approximately 135 religious satellite channels that broadcast guidance and entertainment with an Islamic frame Negotiating Religion and Identity of reference. How do Arab audiences make use of mediated religion in negotiations of identity and belonging? The empirical based case studies in this interdisciplinary volume explore audience-media relations with a focus on religious identity in different countries such as Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Great Britain, Germany, Denmark, and the United States. Arab TV-Audiences Arab The Editor Ehab Galal is Assistant Professor in Media and Society in the Middle East at the Depart- ment of Cross Cultural and Regional Studies at the University of Copenhagen (Denmark). He has specialised in Arab and Islamic media in local and global contexts. ISBN 978-3-631-65611-2 www.peterlang.com Galal (ed.) Galal (ed.) Ehab Galal (ed.) Ehab Galal (ed.) Arab TV-Audiences Today the relations between Arab audiences and Arab media are characterised by plural- ism and fragmentation. More than a thousand Arab satellite TV channels alongside oth- er new media platforms are offering all kinds of programming. Religion has also found a Arab TV-Audiences vital place as a topic in mainstream media or in one of the approximately 135 religious satellite channels that broadcast guidance and entertainment with an Islamic frame Negotiating Religion and Identity of reference. -

A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East

A POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC DICTIONARY OF THE MIDDLE EAST A POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC DICTIONARY OF THE MIDDLE EAST David Seddon FIRST EDITION LONDON AND NEW YORK First Edition 2004 Europa Publications Haines House, 21 John Street, London WC1N 2BP, United Kingdom (A member of the Taylor & Francis Group) This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” © David Seddon 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be photocopied, recorded, or otherwise reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN 0-203-40291-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-40992-2 (Adobe e-Reader Format) ISBN 1 85743 212 6 (Print Edition) Development Editor: Cathy Hartley Copy Editor and Proof-reader: Simon Chapman The publishers make no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may take place. FOREWORD The boundaries selected for this first Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East may appear somewhat arbitrary. It is difficult to define precisely ‘the Middle East’: this foreword attempts to explain the reasoning behind my selection. For the purposes of this Dictionary, the region includes six countries and one disputed territory in North Africa (Mauritania, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt and Western Sahara), eight countries in Western Asia (Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, Iraq and Iran), seven in Arabia (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain and Yemen), five newly independent states in southern Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) and Afghanistan. -

The Absence of Middle Eastern Great Powers: Political "Backwardness" in Historical Perspective

The Absence of MiddleEastern Great Powers:Political ‘ ‘Backwardness’’ in HistoricalPerspective IanS. Lustick Propelledby theoil boom of the mid-1970s the Middle East emerged as theworld’ s fastestgrowing region. 1 Hopesand expectations were highfor Arab politicalconsoli- dation,economic advancement, and cultural efflorescence. With falling oil prices and adevastatingwar betweenIran andIraq, these hopes had dimmed somewhat by the early1980s. In 1985, however, the spectacular image of an Arab greatpower was stilltantalizing. A Pan-Arabstate, wrote two experts on the region, would include a totalarea of 13.7million square kilometers, secondonly to theSoviet Union and considerably larger than Europe, Canada, China,or the United States. ..By2000it wouldhave more people than either ofthetwo superpowers. This state would contain almost two-thirds of the world’s provenoil reserves. It would also have enough capital to nanceits own economicand social development. Conceivably, it couldfeed itself. ..Access toahugemarket could stimulate rapid industrial growth. Present regional in- equalitiescould ultimately be lessenedand the mismatch between labor-surplus andlabor-short areas corrected. The aggregate military strength and political inuence of this strategically located state would be formidable.. ..Itis easyto comprehendwhy this dream has long intoxicated Arab nationalists. 2 Withinten years, however, this assessment sounded more like a fairytale than a scenario.Indeed the last two decades have been dispiriting for Arab nationalists,not onlymeasured against the prospectof agreatnational state, but compared to levelsof Iam gratefulfor helpful comments made onpreliminary drafts of this article byThomasCallaghy, MelaniCammett, AveryGoldstein, Steven Heydemann, Friedrich Kratochwil, Sevket Pamuk, and this journal’s anonymousreviewers. Thepaper on which this article is basedwas originallyprepared for a January1996 workshop on ‘ ‘Regionalismand the Middle East’ ’ organizedunder the auspices ofthe Joint Near andMiddle East Committee oftheSocial Science Research Council. -

Remember Baghdad Press Pack

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE FILM TIMELINE HISTORY CONTRIBUTORS DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT PRODUCTION TEAM FURTHER READING CONTACTS TRAILER www.vimeo.com/198711108 spring films INTRODUCTION Iraq’s last Jews tell the story of their country On the hundredth anniversary of the British invasion in 1917, Remember Baghdad is the untold story of Iraq, an unmissable insight into how the country developed from a completely new perspective – through the eyes of the Jews who lived there for 2,600 years until only a generation ago. With vivid home movies and archive news footage, eight characters tell their remarkable stories, of fun that was had, and the fear that followed as Iraq laid foundations for decades of unrest. Amid the country’s instability today we follow one Iraqi Jew on a journey home, Baghdad in the 1950s back to Baghdad. The story begins in a happy period for the Jews. In 1917 a third of the citizens of Baghdad are Jewish. The descendants of the scholars who wrote the Babylonian Talmud are now westernising fast. In 1947 the first Miss Baghdad is Jewish. Jews are parliamentarians. They attend fancy parties and picnics on the Tigris with the elite. But after the creation of Israel they are no longer safe. A mass exodus takes place, though many thousands stay behind, loyal to the country they love. Finally, after 1967, Saddam Hussein mobilises a mass movement against them and they must flee. Our characters tell their story with poignant regret and bitter clarity. uy a house in Iraq Edwin Shuker wants to b r the future to plant a seed of hope fo REMEMBER BAGHDAD www.rememberbaghdad.com THE FILM Five families from the Jewish community look back on a scarcely imaginable time in Baghdad – Iraq was booming, it was pleasure-seeking, and there was inter-communal trust. -

"Palestinian Nationalism and the Struggle for National Self-Determination," in Berch Berberoglu, Ed., the National

"Palestinian Nationalism and the Struggle for National Self-Determination," in Berch Berberoglu, ed., The National Question (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995), pp. 15-35 by Gordon Welty Wright State University Dayton, OH 45435 USA [//15] The development of the Palestinian national movement can be traced back at least to the beginning of the twentieth century, when the crumbling Ottoman Empire gave rise by the end of the First World War to the territorial expansion of the Western imperialist powers -- including France, Britain, and later the United States -- into the Middle East. Palestine, the provincial territory controlled by the Ottoman state, had for centuries been home to the Palestinian people. But while successful national uprisings in the Balkans and elsewhere in the Empire led to the establishment of independent nation states, the area inhabited by the Palestinians and the surrounding regions extending to the Persian Gulf and the Arabian peninsula came under the control of the European powers which intervened and turned them into mandates of one or another of the leading imperialist states of the period -- Britain and France. This occupation of Arab territories by the Western powers intensified with the creation of the State of Israel on Palestinian lands at mid-century. The Zionist oppression of the Palestinian people in Israel, their forced expulsion from their homeland to neighboring Arab states as refugees, and their harsh treatment by the Zionist state in the occupied territories of Gaza and the West Bank during the 1970s and 1980s have given rise to a strong sense of national identity and to a struggle for national independence which culminated in the popular uprising known as the Intifada.