Chapter 10.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015–2016 Annual Report

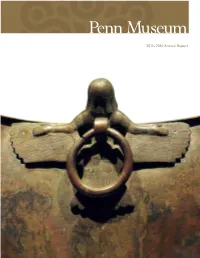

2015–2016 Annual Report 2015–2016 Annual Report 3 EXECUTIVE MESSAGE 4 THE NEW PENN MUSEUM 7 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE GEOGRAPHY 8 Teaching & Research: Penn Museum-Sponsored Field Projects 10 Excavations at Anubis-Mountain, South Abydos (Egypt) 12 Gordion Archaeological Project (Turkey) — Historical Landscape Preservation at Gordion — Gordion Cultural Heritage Education Project 16 The Penn Cultural Heritage Center — Conflict Culture Research Network (Global) — Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria & Iraq Project (Syria and Iraq) — Tihosuco Heritage Preservation & Community Development Project (Mexico) — Wayka Heritage Project (California, USA) 20 Pelekita Cave in Eastern Crete (Greece) 21 Late Pleistocene Pyrotechnology (France) 22 The Life & Times of Emma Allison (Canada) 23 On the Wampum Trail (North America) 24 Louis Shotridge & the Penn Museum (Alaska, USA) 25 Smith Creek Archaeological Project (Mississippi, USA) 26 Silver Reef Project (Utah, USA) 26 South Jersey (Vineland) Project (New Jersey, USA) 27 Collections: New Acquisitions 31 Collections: Outgoing Loans & Traveling Exhibitions 35 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE NUMBERS 40 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE MONTH 57 SUPPORTING THE MISSION 58 Leadership Supporters 62 Loren Eiseley Society 64 Expedition Circle 66 The Annual Fund 67 Sara Yorke Stevenson Legacy Circle 68 Corporate, Foundation, & Government Agency Supporters Objects on the cover, inside cover, and above were featured 71 THE GIFT OF TIME in the special exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas, from 72 Exhibition Advisors & Contributors February 13, 2016 through November 27, 2016. 74 Penn Museum Volunteers On the cover: Bronze cauldron with siren and demon 76 Board of Overseers attachments. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations 18516. -

Body of Pennsylvania, the Atwater-Kent Museum, the Museum

REVIEWS 239 Philadelphia and the Development of papers offers an important and coherent account Americanist Archaeology of one major American city’s contributions to Don D. Fowler and David R. Wilcox the intellectual development of archaeology as a learned profession in the Americas. (editors) Curtis M. Hinsley’s sweeping and finely University of Alabama Press, crafted contribution leads off the volume with Tuscaloosa, 2003. xx+246 pp., 13 an insightful analysis of Philadelphia’s late-19th illus. $65.00 cloth. century social milieu that set the city apart from Boston, New York, and other eastern cities as Being a native Philadelphian, I had the good a center of intellectual foment. Hinsley sagely fortune early on to come under the infl uence observes that it was Philadelphia’s late-19th- of the cultural opportunities offered by the city. century atmosphere of “business aristocracy” Many of Philadelphia’s venerable institutions and genteel wealth that ultimately created the were routinely on my family’s list of places climate that allowed for the leaders of the to visit when going “into town,” including the city’s institutions to become some of the coun- Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, the try’s prime players in the developing fi eld of Philadelphia Academy of Music, the Franklin archaeology. Presaging some of the later chap- Institute, the Philadelphia Art Museum, and the ters in the volume, Hinsley identifi es these key University Museum of the University of Penn- players as Daniel G. Brinton, Sara Stevenson, sylvania. In my career, I soon became aware of Stewart Culin, Charles C. -

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES in the HISTORY of ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O. Murray Cultural Negotiations The Role of Women in the Founding of Americanist Archaeology DAVID L. BROWMAN University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London © 2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Browman, David L. Cultural negotiations: the role of women in the founding of Americanist archaeology / David L. Browman. pages cm.— (Critical studies in the history of anthropology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8032-4381-1 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. Women archaeologists—Biography. 2. Archaeology—United States—History. 3. Women archaeologists—History. 4. Archaeologists—Biography. I. Title. CC110.B76 2013 930.1092'2—dc23 2012049313 Set in Lyon by Laura Wellington. Designed by Nathan Putens. Contents Series Editors’ Introduction vii Introduction 1 1. Women of the Period 1865 to 1900 35 2. New Directions in the Period 1900 to 1920 73 3. Women Entering the Field during the “Roaring Twenties” 95 4. Women Entering Archaeology, 1930 to 1940 149 Concluding Remarks 251 References 277 Index 325 Series Editors’ Introduction REGNA DARNELL AND STEPHEN O. MURRAY David Browman has produced an invaluable reference work for prac- titioners of contemporary Americanist archaeology who are interested in documenting the largely unrecognized contribution of generations of women to its development. Meticulous examination of the archaeo- logical literature, especially footnotes and acknowledgments, and the archival records of major universities, museums, field school programs, expeditions, and general anthropological archives reveals a complex story of marginalization and professional invisibility, albeit one that will be surprising neither to feminist scholars nor to female archaeologists. -

Sara Yorke Stevenson Papers

Sara Yorke Stevenson Papers Sara Yorke Stevenson (1847-1921), archeologist, Egyptologist, civic leader, newspaper editor and columnist, was one of the principal founders of what is now called the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology; In 1894 she became the first woman to receive an honorary degree from Penn. Stevenson served as Curator of the Egyptian and Mediterranean Section and member of the Museum’s governing board from 1890 to 1905, but she resigned in 1905––apparently over the Board’s handling of disputes about Hermann Hilprecht, Curator of the Babylonian Section. Founder and first president of the Equal Franchise Society, co-founder and two- term president of the Civic Club (a women’s group pushing for reform and civic improvement), chair of the French War Relief Committee of the Emergency Aid of Pennsylvania, Stevenson played a leadership role in many of Philadelphia’s “good causes.” For more than a decade she was also literary editor and columnist for the Philadelphia Public Ledger, writing under the pen names “Peggy Shippen” and “Sallie Wistar.” These papers (1.8 cubic feet), removed in 2006 from a home once lived in by Stevenson’s friend Frances Anne Wister (1874-1956), cover the full range of Stevenson’s interests. Highlights include her newspaper clippings and comments on the Hilprecht dispute, copies of hundreds of letters to her from her good friend William Pepper, Jr. (1898; provost at Penn, civic leader), and letters to her from many other Philadelphia notables. Donation of David Prince Estate -

George B. Gordon Director's Office Records 0001.03 Finding Aid Prepared by Elizabeth Eyermann

George B. Gordon Director's Office Records 0001.03 Finding aid prepared by Elizabeth Eyermann. Last updated on March 02, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Penn Museum Archives August 12, 2013 George B. Gordon Director's Office Records Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 General note...................................................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Alphabetical Correspondence.................................................................................................................. 7 - Page 2 - George B. Gordon Director's Office Records Summary Information Repository -

Zelia Nuttall Papers 1056 Finding Aid Prepared by Kathleen Baxter, Maureen Callahan

Zelia Nuttall papers 1056 Finding aid prepared by Kathleen Baxter, Maureen Callahan. Last updated on March 03, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Penn Museum Archives 2009 Zelia Nuttall papers Table of Contents Summary Information...................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History.........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents.......................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................4 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings......................................................................................................................... 5 Related Items note.........................................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... 7 Correspondence.......................................................................................................................................7 -

Frank Hamilton Cushing: Pioneer Americanist

Frank Hamilton Cushing: pioneer Americanist Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Brandes, Ray, 1924- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 14:52:04 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565633 FRANK HAMILTON CUSHING: PIONEER AMERICANIST by Ra y m o n d Stewart Brandes A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 5 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Raymond Stewart Brandes____________________ entitled "Frank Hamilton Cushing: Pioneer Americanist11 be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* X t o m /r (90^ jjLar . A y ,, (r i ?6 S ~ ~ *This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library0 ' Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission^ provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is ma d e 0 . -

Sara Yorke Stevenson Papers 1162

Sara Yorke Stevenson papers 1162 Last updated on March 02, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Penn Museum Archives July 2011 Sara Yorke Stevenson papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - Sara Yorke Stevenson papers Summary Information Repository University of Pennsylvania: Penn Museum Archives Creator Stevenson, Sara Yorke, 1847-1921 Title Sara Yorke Stevenson papers Call number 1162 Date [bulk] 1898-1905 Date [inclusive] 1890-1905 Extent 0.2 linear foot () Language English Abstract -

A Brief History of the Penn Museum

he founding of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology was A Brief part of the great wave of institution-building that took place in the United States after the Civil War. It was an outgrowth of the rising promi- History of nence of the new country and its belief in the ideals of prog- Tress and manifest destiny. The 1876 Centennial Exposition, held in Philadelphia, introduced America as a new industrial tHe Penn world power and showcased the city as embodying the coun- try’s strength. The United States, however, still lagged behind Europe in MuseuM universities and museums, as well as significant contributions to architecture and the arts. The new wealth created after the Civil War helped to overcome these deficiencies as philan- By AlessAndro PezzAti thropy became a means of earning social recognition, and witH JAne HickMAn And many wealthy and civic-minded Americans thus turned their AlexAndrA fleiscHMAn attention to cultural life and institutions. Philadelphia was at the center of the industrial and cultural ethos of the times. It was known for its manufacturing, rail- roads, and commerce, but also for its institutions of learning, such as the American Philosophical Society, the Academy of Natural Sciences, and the University of Pennsylvania. 4 volume 54, number 3 expedition 125years Top, pictured is a postcard from the 1876 Centennial Exposition in which Philadelphia emerged onto the world stage. Bottom left, as founder of the University Museum, William Pepper, Jr., M.D., L.L.D. (1843–1898), served as University Provost from 1881 to 1894; he was President of the Board of Managers of the Museum from 1894 to 1898. -

Museums, Native American Representation, and the Public

MUSEUMS, NATIVE AMERICAN REPRESENTATION, AND THE PUBLIC: THE ROLE OF MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY IN PUBLIC HISTORY, 1875-1925 By Nathan Sowry Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences July 12, 2020 Date 2020 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 © COPYRIGHT by Nathan Sowry 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Leslie, who has patiently listened to me, aided me, and supported me throughout this entire process. And for my parents, David Sowry and Rebecca Lash, who have always encouraged the pursuit of learning. MUSEUMS, NATIVE AMERICAN REPRESENTATION, AND THE PUBLIC: THE ROLE OF MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY IN PUBLIC HISTORY, 1875-1925 BY Nathan Sowry ABSTRACT Surveying the most influential U.S. museums and World’s Fairs at the turn of the twentieth century, this study traces the rise and professionalization of museum anthropology during the period now referred to as the Golden Age of American Anthropology, 1875-1925. Specifically, this work examines the lives and contributions of the leading anthropologists and Native collaborators employed at these museums, and charts how these individuals explained, enriched, and complicated the public’s understanding of Native American cultures. Confronting the notion of anthropologists as either “good” or “bad,” this study shows that the reality on the ground was much messier and more nuanced. Further, by an in-depth examination of the lives of a host of Native collaborators who chose to work with anthropologists in documenting the tangible and intangible cultural heritage materials of Native American communities, this study complicates the idea that anthropologists were the sole creators of representations of American Indians prevalent in museum exhibitions, lectures, and publications. -

Sara Yorke Stevenson 1847- 1922 by Barbara S. Lesko

Sara Yorke Stevenson 1847- 1922 by Barbara S. Lesko The first curator of the Egyptian Section of the University of Pennsylvania’s Free Museum of Science and Art (now known as the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology), Sara Yorke Stevenson was a wealthy Philadelphian lady who had become a member of the American branch of the Egypt Exploration Fund, founded by Amelia B. Edwards (q.v.) in London in 1882. That Mrs. Stevenson had such an important position at the Museum at such an early time was due in part to the enlightened Dr. William Pepper, Provost of the University, who was also involved with developing the archaeological interests of Phoebe Apperson Hearst (q.v.). Thus two wealthy, intelligent, and managerial women on opposite sides of the North American continent came to be intimately and importantly involved with giving Egyptian archaeology a firm basis in the United States. Sara Yorke was born of American parents in Paris on February 19, 1847 and spent the first fifteen years of her life there. Her father, Edward Yorke, was a plantation owner in Louisiana and also a banker. It was in Paris, among the collections of the Louvre most probably, that Sara (named for her mother Sarah Hanna) developed at a young age her life-long interest in ancient Egypt. In 1862 her family settled in Mexico, where she lived for five years. The Yorkes then moved to the United States, settling in Vermont. However, Sara, when she reached the age of 21, went to Philadelphia to live with some aged relatives of her father. -

Zelia Nuttall Papers 1056 Finding Aid Prepared by Kathleen Baxter, Maureen Callahan

Zelia Nuttall papers 1056 Finding aid prepared by Kathleen Baxter, Maureen Callahan. Last updated on March 03, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Penn Museum Archives 2009 Zelia Nuttall papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Related Items note......................................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Correspondence........................................................................................................................................8