Museums, Native American Representation, and the Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Music of the Indians of British Columbia by FRANCES DENSMORE

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 136 Anthropological Papers, No. 27 Music of the Indians of British Columbia By FRANCES DENSMORE FOREWORD Many tribes and locations are represented in the present work, differing from the writer's former books,^ which have generally con- sidered the music of only one tribe. This material from widely sep- arated regions was available at Chilliwack, British Columbia, during the season of hop-picking, the Indians being employed in the fields. The work was made possible by the courtesy of Canadian officials. Grateful acknowledgment is made to Dr. Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent General, Department of Indian Affairs at Ot- tawa, who provided a letter of credential, and to Mr. C. C. Perry, In- dian agent at Vancouver, and Indian Commissioner A. O. N. Daunt, Indian agent at New Westminster, who extended assistance and co- operation. Acknowledgment is also made of the courtesy of Walter Withers, corporal (later sergeant). Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who acted as escort between Chilliwack and the hop camp, and as- sisted the work in many ways. Courtesies were also extended by municipal officers in Chilliwack and by the executive office of the Columbia Hop Co., in whose camp the work was conducted. This is the writer's first musical work in Canada and the results are important as a basis of comparison between the songs of Canad- ian Indians and those of Indians residing in the United States. On this trip the writer had the helpful companionship of her sis- ter, Margaret Densmore. iSee bibliography (Densmore, 1910, 1913, 1918, 1922, 1923, 1926, 1928, 1929, 1929 a, 1929 b, 1932, 1932 a, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1942). -

A. L. Kroeber Papers, 1869-1972

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf3d5n99tn No online items Guide to the A. L. Kroeber Papers, 1869-1972 Processed by Xiuzhi Zhou Jane Bassett Lauren Lassleben Claora Styron; machine-readable finding aid created by James Lake The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note History --History, University of California --History, UC BerkeleyGeographical (by Place) --University of California --University of California BerkeleySocial Sciences --AnthropologySocial Sciences --Area and Interdisciplinary Studies --Native American Studies Guide to the A. L. Kroeber BANC FILM 2049 BANC MSS C-B 925 1 Papers, 1869-1972 Guide to the A. L. Kroeber Papers, 1869-1972 Collection number: BANC FILM 2049 BANC MSS C-B 925 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: Xiuzhi Zhou Jane Bassett Lauren Lassleben Claora Styron Date Completed: 1997 Encoded by: James Lake © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: A. L. Kroeber Papers, Date (inclusive): 1869-1972 Collection Number: BANC FILM 2049 BANC MSS C-B 925 Creator: Kroeber, A. L. (Alfred Louis), 1876-1960 Extent: Originals: 40 boxes, 21 cartons, 14 volumes, 9 oversize folders (circa 45 linear feet)Copies: 187 microfilm reels: negative (Rich. -

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCHES and STUDIES No 4, 2014 3 a Lithuanian “Ethnographic Village”: Heritage, Private Property

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCHES AND STUDIES No 4, 2014 A Lithuanian “Ethnographic Village”: Heritage, Private Property, Entitlement Kristina Jonutyte Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Address correspondence to: Kristina Jonutyte, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, PO Box 11 03 51, 06017 Halle (Saale) Germany. Ph.: +49 (0) 345 2927 0; Fax: +49 (0) 345 2927 502; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this article, various aspects of engagement with the past and with heritage are explored in the context of Grybija village in southern Lithuania. The village in question is a heritage site within an "ethnographic villages" programme, which was initiated by the Soviet state and continued by Independent Lithuania after 1990. The article thus looks at the ideological aspects of heritage as well as its practical implications to Grybija's inhabitants. Moreover, local ideas about private property, righteous ownership and entitlement are explored in their complexity and in relation to the heritage project. Since much of the preserved heritage in the village is private property, various restrictions and prohibitions are imposed on local residents, which are deemed as neither righteous nor effective by many locals. In the meantime, the discourse of the "ethnographic villages" project exotifies and distances the village and its inhabitants, constructing an "Other" that is both admired and alienated. Keywords: heritage site, private property, Lithuania. The fieldsite Grybija is a small village in the far South of Lithuania, Dzūkija region. There are around 50 permanent inhabitants and another dozen or so who stay for the summer, plus weekend visitors.1 The village is in the territory of Dzūkijos National Park which was established in order to protect the landscape as well as natural and cultural monuments of the region. -

A Cultural View of Music Therapy: Music and Beliefs of Teton Sioux Shamans, with Reference to the Work of Frances Densmore

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 5-1999 A Cultural View of Music Therapy: Music and Beliefs of Teton Sioux Shamans, with Reference to the Work of Frances Densmore Stephanie B. Thorne Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Thorne, Stephanie B., "A Cultural View of Music Therapy: Music and Beliefs of Teton Sioux Shamans, with Reference to the Work of Frances Densmore" (1999). Graduate Thesis Collection. 253. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/253 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -- CERTIFICATE FORM Name of Candidate: Stephanie B. Thome Oral Examination Date: ___W=e",dn",e",s",d""aYz."",J",un",-e"--"2"-3,~1,,,,9 ,,,,9,,,9,---________ COmmUtteeChaUpe~on: __~D~r~.~P~enn~y~D~Urun~~i~c~k ______________________ Committee Members: Dr. Sue Kenyon, Dr. Tim Brimmer, Dr. Wayne Wentzel, Mr. Henry Leck Thesis Title: A Cultural View of Music Therapy: Music and Beliefs of Teton Shamans, with Reference to the Work of Frances Densmore Thesis approved in final fonn: """"" Date: ____________:::::~ _________ Major professor: __----'D"'r"' . ..!.P-"e"'nn"'y.L...!.D"'im!!.!!.m""'ic"'k~ ___________________________ II • A CULTURAL VIEW OF MUSIC THERAPY: MUSIC AND BELIEFS OF TETON SIOUX SHAMANS, WITH REFERENCE TO THE WORK OF FRANCES DENSMORE by Stephanie B. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

2017 Fernald Caroline Dissert

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE VISUALIZATION OF THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST: ETHNOGRAPHY, TOURISM, AND AMERICAN INDIAN SOUVENIR ARTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CAROLINE JEAN FERNALD Norman, Oklahoma 2017 THE VISUALIZATION OF THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST: ETHNOGRAPHY, TOURISM, AND AMERICAN INDIAN SOUVENIR ARTS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS BY ______________________________ Dr. W. Jackson Rushing, III, Chair ______________________________ Mr. B. Byron Price ______________________________ Dr. Alison Fields ______________________________ Dr. Kenneth Haltman ______________________________ Dr. David Wrobel © Copyright by CAROLINE JEAN FERNALD 2017 All Rights Reserved. For James Hagerty Acknowledgements I wish to extend my most sincere appreciation to my dissertation committee. Your influence on my work is, perhaps, apparent, but I am truly grateful for the guidance you have provided over the years. Your patience and support while I balanced the weight of a museum career and the completion of my dissertation meant the world! I would certainly be remiss to not thank the staff, trustees, and volunteers at the Millicent Rogers Museum for bearing with me while I finalized my degree. Your kind words, enthusiasm, and encouragement were greatly appreciated. I know I looked dreadfully tired in the weeks prior to the completion of my dissertation and I thank you for not mentioning it. The Couse Foundation, the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center, and the School of Visual Arts, likewise, deserve a heartfelt thank you for introducing me to the wonderful world of Taos and supporting my research. A very special thank you is needed for Ginnie and Ernie Leavitt, Carl Jones, and Byron Price. -

Black Lives Matter and Ethnographic Museums

ICME NEWS ISSUE 90 AUGUST 2020 black lives matter and etHnographic museums A statement from ICME Committee Announcements AND NEWS / Exhibitions and Conferences: Announcements and Reviews / ARTICLES / NOTICES ICME NEWS 90 AUGUST 2020 2 CONTENTS Words from the Editor .........................................................3 ICME Board Announcements and News Black Lives Matter and Ethnographic Museums: A Statement from ICME .........................................................4 Postponement of the 2020 ICME Conference ........................5 Exhibitions and Conferences: Announcements and Reviews Conference Review: Absence and Belonging in Museums of Everyday Life – Laurie Cosmo ...............................................6 Conference Review: Beyond collecting; new ethics for museums in transition – Flower Manasse .................................13 Conference Announcement: Anthropology and Geography ......15 Conference Announcement: Mapping South-South Connections ..........................................................16 Film Review: Bang the Drum – Jenny Walklate .......................17 Articles How can Museums Challenge Racism and Colonial Fantasies? - Boniface Mabanza in conversation with Anette Rein ............19 Getting out, getting in: Amerindian and European perspectives around the museum - Rui Mourão .........................25 Kurmanjan Datka. Museum of Nomadic Civilization, The Kyrgyz Republic - Aida Alymova and Gulbara Abdykalykova .............29 Beyond Trophies and Spoils of Wars - Staci-Marie Dehaney ........33 -

Kickapoo Tribe by Jacob

Kickapoo Tribe by Jacob Questions and answers: Where did the tribe live? Where do the people live now? The Kickapoo Indian people are from Michigan and in the area of Great Lakes Regions. Most Kickapoo people still live in Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. What did they eat? The Kickapoo men hunted large animals like deer. They also eat com, cornbread call "'pugna" and planted squash and beans. What did they wear? The women wore wrap around skirts. Men wore breechcloths with leggings. What special ceremonies did they have? The Kickapoo people were very spiritual and connected with animals and they had special ceremonies when it came to hunting. A display of lighting and thunder, usually in early February signifies the beginning of the New Year and hence the cycle of the ceremonies. Some of the ceremonies would be hand drum, dancing and singing. What kind of homes did they build? The Kickapoo people made homes called wickiups and Indian brush shelters. 5 Interesting Facts of the Kickapoo People: 1. Story telling is very important to the Kickapoo Indian culture. 2. Kickapoo hunters & warriors used spears, clubs, bows and arrows to hunt for food. 3. Ho (pronounced like the English word Hoe) is a friendly greeting. 4. Kepilhcihi (pronounced Kehpeeehihhih) means "thank you." 5. The Kickapoo children are just like us. They go to school, like to play and help around the house.. -

De Laguna 1960:102

78 UNIVERSITY ANTHROPOLOGY: EARLY1DEPARTMENTS IN THE UNITED STATES John F. Freeman Paper read before the Kroeber Anthropological Society April 25, 1964, Berkeley, California I. The Conventional View Unlike other social sciences, anthropology prides itself on its youth, seeking its paternity in Morgan, Tylor, Broca, and Ratzel, its childhood in the museum and its maturity in the university. While the decades after 1850 do indeed suggest that a hasty marriage took place between Ethnology, or the study of the races of mankind conceived as divinely created, and Anthropology, or the study of man as part of the zoological world; the marriage only symbol- ized the joining of a few of the tendencies in anthropology and took place much too late to give the child an honest name. When George Grant MacCurdy claimed in 1899 that "Anthropology has matured late," he was in fact only echoing the sentiments of the founders of the Anthropological Societies of Paris (Paul Broca) and London (James Hunt), who in fostering the very name, anthropology, were urging that a science of man depended upon prior develop- ments of other sciences. MacCurdy stated it In evolutionary terms as "man is last and highest in the geological succession, so the science of man is the last and highest branch of human knowledge'" (MacCurdy 1899:917). Several disciples of Franz Boas have further shortened the history of American anthropology, arguing that about 1900 anthropology underwent a major conversion. Before that date, Frederica de Laguna tells us, "anthropologists [were] serious-minded amateurs or professionals in other disciplines who de- lighted in communicating-across the boundaries of the several natural sci- ences and the humanities, [because] museums, not universities, were the cen- ters of anthropological activities, sponsoring field work, research and publication, and making the major contributions to the education of profes- sional anthropologists, as well as serving the general public" (de Laguna 1960:91, 101). -

Fidelia Fielding

Fidelia Fielding Warning: Page using Template:Infobox person with he met up with several Mohegan young men---Burrill unknown parameter “box_width” (this message is shown Tantaquidgeon, Jerome Roscoe Skeesucks, and Edwin only in preview). Fowler---who introduced him to Fielding. This encounter sparked a lifelong friendship with the Tantaquidgeon family. Speck interviewed Fidelia, recording notes on the Fidelia Ann Hoscott Smith Fielding (1827–1908), also known as Dji'ts Bud dnaca (“Flying Bird”), was the Mohegan language that he shared with his professor, John Dyneley Prince, who encouraged further research. Fi- daughter of Bartholomew Valentine Smith (c. 1811- 1843) and Sarah A. Wyyougs (1804-1868), and grand- delia eventually allowed Speck to view her personal day- daughter of Martha Shantup Uncas (1761-1859).[2] books (also called diaries) in which she recorded brief observations on the weather and local events, so that he She married Mohegan mariner William H. Fielding could understand and accurately record the written ver- (1811-1843), and they lived in one of the last “tribe sion of the Mohegan language. houses,” a reservation-era log cabin dwelling. She was known to be an independent-minded woman who was This material that Speck collected from Fidelia Fielding well-versed in tribal traditions, and who continued to inspired four publications in 1903 alone: “The Remnants speak the traditional Mohegan Pequot language during of our Eastern Indian Tribes” in The American Inventor, her elder years.[3] Vol. 10, pp. 266–268; “A Mohegan-Pequot Witchcraft Tale” in Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 16, pp. 104– 107; “The Last of the Mohegans” in The Papoose Vol. -

'Gladys and the Native American Long Long Trail of Tears'

The University of Manchester Research 'Gladys and the Native American Long Long Trail of Tears' Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Newby, A. (2016, Feb 16). 'Gladys and the Native American Long Long Trail of Tears': Reading Race, Collecting Cultures - The Roving Reader Files. Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Relations Resource Centre. https://aiucentre.wordpress.com/2016/02/16/gladys-and-the-native-american-long-long-trail-of-tears/ Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 Gladys and the Native American Long Long Trail of Tears The Roving Reader Files Posted on 16/02/2016 (https://aiucentre.wordpress.com/2016/02/16/gladys-and-the-native-american-long-long-trail- of-tears/) Have you thought about your worldview recently? Do you believe deep down everyone everywhere should think like you? We’ve all done it. -

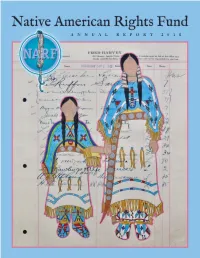

NARF Annual Report 2018(A)

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 NATIVE AMERICAN RIGHTS FUND TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Director’s Report .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Chairman’s Message ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Board of Directors and National Support Committee ........................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Preserving Tribal Existence .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Protecting Tribal Natural Resources .................................................................................................................................... 9 Promoting Human Rights .................................................................................................................................................... 17 Holding Governments Accountable .................................................................................................................................... 24 Developing Indian Law .......................................................................................................................................................