'Gladys and the Native American Long Long Trail of Tears'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geena Clonan

Malta House of Care Geena Clonan: Founding President of the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame In 1993, while working as the Managing Director of the Connecticut Forum, Geena Clonan of Fairfield realized there was a gaping hole in our state – namely, there was no organization or venue that collectively celebrated the achievements of the many, many Connecticut women who had made groundbreaking contribu- tions locally, nationally, and internationally. After consulting with the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca, NY, Geena and her team set about changing that, and in May 1994, established the Connecti- cut Women’s Hall of Fame. Since then, 115 women representing eight different disciplines have been inducted into the Hall – women like Gov. Ella Grasso, opera singer Marian Anderson, Mohegan anthropologist Gladys Tantaquidgeon, and abolitionist Prudence Crandall, to name just a few. In November 2017, three wom- en who have distinguished themselves in law enforcement and military service will be inducted. Their stories, and those of the other inductees, are beautifully told in the “Virtual Hall” on the organization’s web site. Under Geena’s 20+-year leadership as Founding President, the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame re- mained true to its mission “to honor publicly the achievements of Connecticut women, preserve their sto- ries, educate the public and inspire the continued achievements of women and girls.” Says Geena: “It has been personally rewarding and one of my proudest pursuits in community service to tell, through the Connecticut -

Children's Literature Bibliographies

appendix C Children’s Literature Bibliographies Developed in consultation with more than a dozen experts, this bibliography is struc- tured to help you find and enjoy quality literature, and to help you spend more time read- ing children’s books than a textbook. It is also structured to help meet the needs of elementary teachers. The criteria used for selection are • Because it is underused, an emphasis on multicultural and international literature • Because they are underrepresented, an emphasis on the work of “cultural insiders” and authors and illustrators of color • High literary quality and high visual quality for picture books • Appeal to a dual audience of adults and children • A blend of the old and the new • Curricular usefulness to practicing teachers • Suitable choices for permanent classroom libraries Many of the books are award winners. To help you find books for ELLs, I have placed a plus sign (+) if the book is writ- ten in both English and another language. To help you find multicultural authors and il- lustrators, I have placed an asterick (*) to indicate that the author and/or illustrator is a member of underrepresented groups. They are also often cultural insiders. I identify the ethnicity of the authors only if they are is clearly identified in the book. Appendix D in Encountering Children’s Literature: An Arts Approach by Jane Gangi (2004) has a com- plete list of international and multicultural authors who correspond with the astericks. Some writers and illustrators of color want to be known as good writers and good illustrators, not as good “Latino” or “Japanese American” writers and/or illustrators. -

Great Women in Connecticut History

GREAT WOMEN IN CONNECTICUT HISTORY PERMANENT COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN 6 GRAND STREET HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT AUGUST 26, 1978 COMMISSIONERS OF THE PERMANENT COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN Sh irley R. Bysiewicz, Chairperson Lucy Johnson, Vice Chairperson Helen Z . Pearl, Treasurer Diane Alverio Dorothy Billington Thomas I. Emerson Mary Erlanger Mary F. Johnston Barbara Lifton, Esq . Minerva Neiditz Flora Parisky Chase Going Woodhouse LEGISLATIVE COMMISSION MEMBERS Betty Hudson, Senator Nancy Johnson, Senator Charles Matties, Representative Margaret Morton, Representative STAFF MEMBERS Susan Bucknell, Executive Director Fredrica Gray, Public Information Coordinator Linda Poltorak, Office Administrator Jeanne Hagstrom, Office Secretary Elba I. Cabrera, Receptionist/Typist " ... when you put your hand to the plow, you can't put it down until you get to the end of the row. " -Alice Paul CREDITS Project Coordinator: Fredrica Gray, Public Information Coordinator. Review and Comment: Susan Bucknell, Executive Director, PCSW and Lucy Johnson, Chair of the PCSW Public Information Committee Initial Research and First Draft: Shawn Lampron Follow-up Research and Second Draft: Erica Brown Wood Production Typist: Elba Cabrera Special Assistance for the Project was given by: Shirley Dobson, Coleen Foley, Lynne Forester, Sharice Fredericks, Lyn Griffen, Andrea Schenker, and Barbara Wilson Student Artists from Connecticut High Schools: Nancy Allen for her illustration of Alice Paul, Kathleen McGovern for her illustration of Josephine Griffing, -

Museums, Native American Representation, and the Public

MUSEUMS, NATIVE AMERICAN REPRESENTATION, AND THE PUBLIC: THE ROLE OF MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY IN PUBLIC HISTORY, 1875-1925 By Nathan Sowry Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences July 12, 2020 Date 2020 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 © COPYRIGHT by Nathan Sowry 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Leslie, who has patiently listened to me, aided me, and supported me throughout this entire process. And for my parents, David Sowry and Rebecca Lash, who have always encouraged the pursuit of learning. MUSEUMS, NATIVE AMERICAN REPRESENTATION, AND THE PUBLIC: THE ROLE OF MUSEUM ANTHROPOLOGY IN PUBLIC HISTORY, 1875-1925 BY Nathan Sowry ABSTRACT Surveying the most influential U.S. museums and World’s Fairs at the turn of the twentieth century, this study traces the rise and professionalization of museum anthropology during the period now referred to as the Golden Age of American Anthropology, 1875-1925. Specifically, this work examines the lives and contributions of the leading anthropologists and Native collaborators employed at these museums, and charts how these individuals explained, enriched, and complicated the public’s understanding of Native American cultures. Confronting the notion of anthropologists as either “good” or “bad,” this study shows that the reality on the ground was much messier and more nuanced. Further, by an in-depth examination of the lives of a host of Native collaborators who chose to work with anthropologists in documenting the tangible and intangible cultural heritage materials of Native American communities, this study complicates the idea that anthropologists were the sole creators of representations of American Indians prevalent in museum exhibitions, lectures, and publications. -

THE ROLE of GLADYS Tantaquidgefjn

THE ROLE OF GLADYS TANTAQUIDGEfJN MELISSA FAWCETr University of Connecticut The identity of the Mohegan people has been preserved as well as challenged by interaction with the non-Indian. This paradox has been sustained by three outstanding tribal leaders born in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, respectively. When a splinter-group of the Pequot nation first formed the Mohegan tribe in the 1620's, the rebels were an insecure minor ity within both the Indian and non-Indian world.l Forced to ally with the Puritans for survival, the Mohegan chief, Uncas, was nonetheless able to limit cultural contamination through his pragmatism and manipulative diplomacy. Mter U ncas' death in 1683, the devastating effects of accul turation combined with a power vacuum created a nearly dis astrous cultural and demographic degeneration. This trend was reversed in the mid 1700s by Samsom Occum. As a congre gational minister and skilled Indian woodsman, he was able to establish schools for his people with curriculum that balanced traditional and modern skills. Having survived the ravages of contact and acculturation by the creative implementation of non-lndian military and educa tional skills, the Mohegan had yet to face an even greater chal lenge. Mter the reservation was eliminated in 1861, cultural identity became increasingly difficult to maintain. By the late 1 This view of Mohegan origins is popular within the tribe itself. For the currently accepted scholarly interpretation see Neal Salisbury (1982). 136 MELISSA FAWCETT 19th century tribal elders were often too apathetic, too fearful or too skeptical of their offspring to pass on their knowledge. -

Native American Sourcebook: a Teacher's Resource on New England Native Peoples. INSTITUTION Concord Museum, MA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 406 321 SO 028 033 AUTHOR Robinson, Barbara TITLE Native American Sourcebook: A Teacher's Resource on New England Native Peoples. INSTITUTION Concord Museum, MA. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 238p. AVAILABLE FROMConcord Museum, 200 Lexington Road, Concord, MA 01742 ($16 plus $4.95 shipping and handling). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Culture; American Indian History; *American Indian Studies; *Archaeology; Cultural Background; Cultural Context; *Cultural Education; Elementary Secondary Education; Instructional Materials; Social Studies; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Algonquin (Tribe); Concord River Basin; Native Americans; *New England ABSTRACT A major aim of this source book is to provide a basic historical perspective on the Native American cultures of New England and promote a sensitive understanding of contemporary American Indian peoples. An emphasis is upon cultures which originated and/or are presently existent in the Concord River Basin. Locally found artifacts are used in the reconstruction of past life ways. This archaeological study is presented side by side with current concerns of New England Native Americans. The sourcebook is organized in six curriculum units, which include:(1) "Archaeology: People and the Land";(2) "Archaeology: Methods and Discoveries";(3) "Cultural Lifeways: Basic Needs";(4) "Cultural Lifeways: Basic Relationships"; (5) "Cultural Lifeways: Creative Expression"; and (6) "Cultural Lifeways: Native Americans Today." Background information, activities, and references are provided for each unit. Many of the lessons are written out step-by-step, but ideas and references also allow for creative adaptations. A list of material sources, resource organizations and individuals, and an index conclude the book. -

Hartford's Ann Plato and the Native Borders of Identity

Hartford’s Ann Plato and the Native Borders of Identity Hartford’s Ânn Plato and the Native Borders of Identity RON WELBURN SUNY PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2015 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production and book design, Laurie D. Searl Marketing, Kate R. Seburyamo Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Welburn, Ron, 1944– Hartford’s Ann Plato and the native borders of identity / Ron Welburn. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4384-5577-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4384-5578-5 (ebook) 1. Plato, Ann—Criticism and interpretation. 2. African American women authors. 3. African American women educators. 4. Hartford (Conn.)—Intellectual life. I. Title. PS2593.P347Z93 2015 818'.309—dc23 2014017459 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Missinnuok of Towns and Cities Contents Figures and Maps ix Prologue xi Acknowledgments xiii A Speculative and Factual Chronology for Ann Plato xvii Introduction 1 1. Ann Plato: Hartford’s Literary Enigma 17 2. “The Natives of America” and “To the First of August”: Contrasts in Cultural Investment 33 3. -

State of Vermont's Response to Petition for Federal

STATE OF VERMONT‘S RESPONSE TO PETITION FOR FEDERAL ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF THE ST. FRANCIS/SOKOKI BAND OF THE ABENAKI NATION OF VERMONT STATE OF VERMONT WILLIAM H. SORRELL, ATTORNEY GENERAL Eve Jacobs-Carnahan, Special Assistant Attorney General December 2002 Second Printing, January 2003 CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................. v MAP ......................................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................. vii INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................1 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND...............................................................................................1 Historic Tribe Elusive ...................................................................................................1 Major Scholars of the Western Abenakis .....................................................................3 SEVENTEENTH CENTURY .......................................................................................5 Seventeenth-Century History is Sketchy ......................................................................5 Some Noteworthy Events of the Seventeenth-Century ................................................7 EIGHTEENTH CENTURY ..........................................................................................8 -

47Th Annual Convention

MLA Northeast Modern Language Association 47th Annual Convention March 17–20, 2016 HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT Local Host: University of Connecticut Administrative Sponsor: University at Buffalo 2 3 CONVENTION STAFF Executive Director Local Liaisons Carine Mardorossian Cathy Schlund-Vials University at Buffalo University of Connecticut Emma Burris-Janssen Associate Executive Director University of Connecticut Brandi So Stony Brook University, SUNY Sarah Moon University of Connecticut Administrative Coordinator Graduate Assistant/Webmaster Renata Towne University at Buffalo Jesse Miller University at Buffalo Chair Coordinator CV Clinic Organizer Kristin LeVeness SUNY Nassau Community College James Van Wyck Fordham University Marketing Coordinator Derek McGrath Stony Brook University, SUNY FELLOWS Book Award Assistant Panel Assistant Shayna Israel Paul Beattie University at Buffalo University at Buffalo Events Assistant Summer Fellowship Assistant Sarah Goldbort Leslie Nickerson University at Buffalo University at Buffalo Exhibitor Assistant Travel Awards Assistant Joshua Flaccavento Nicole Lowman University at Buffalo University at Buffalo 4 BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Benjamin Railton | Fitchburg State University First Vice President Hilda Chacón | Nazareth College Second Vice President Maria DiFrancesco | Ithaca College Past President Daniela B. Antonucci | Princeton University Anglophone/American Literature Director John Casey | University of Illinois at Chicago Anglophone/British Literature Director Susmita Roye | Delaware State University -

Sponsorship Opportunities

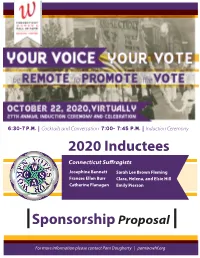

6:30-7 P.M. | Cocktails and Conversation 7:00- 8:00 P.M. | Induction Ceremony 2020 Inductees Connecticut Suffragists Josephine Bennett Sarah Lee Brown Fleming Frances Ellen Burr Clara, Helena, and Elsie Hill Catherine Flanagan Emily Pierson Sponsorship Proposal For more information please contact Pam Dougherty | [email protected] Sponsporships At - A - Glance “Did You Company Logo on Mention in Sponsor Sponsorship Welcome Commercial Know” Website, Social Media Investment Event Tickets Media Level Opportunities Video Spot Video Platforms and all Outreach (10 sec) Marketing Materials Title $10,000 Lead Sponsor 30 Seconds Unlimited Sponsorship Gold Spotlight $7,500 Activity Room 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Activity Room Gold Spotlight Centenninal $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Prize Package Activity Room Gold Spotlight $7,500 Mirror Mirror 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Room Gold Spotlight Women Who $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Run Room Gold Spotlight Show Me the $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Money Room General Chat Silver $5,000 15 Seconds Unlimited Room Bronze $3,000 Logo Listing Unlimited Why Your Sponsorship Matters COVID-19 has created many challenges for our community, and women and students are particularly impacted. At the Hall, we are working diligently to ensure that our educational materials are available online while parents, students, and community members work from home and that our work remains relevant to the times. We are moving forward to offer even more programs that support our community’s educational needs, from collaborating with our Partners to offer virtual educational events like at-home STEM workshops, to our new webinar series, “A Conversation Between”, which creates a forum for women to discuss issues that matter to them with leaders in our community. -

Sponsorship Proposal 2020 Inductees

6:30-7 P.M. | Cocktails and Conversation 7:00- 7:45 P.M. | Induction Ceremony 2020 Inductees Connecticut Suffragists Josephine Bennett Sarah Lee Brown Fleming Frances Ellen Burr Clara, Helena, and Elsie Hill Catherine Flanagan Emily Pierson Sponsorship Proposal For more information please contact Pam Dougherty | [email protected] Sponsporships At - A - Glance “Did You Company Logo on Mention in Sponsor Sponsorship Welcome Commercial Know” Website, Social Media Investment Event Tickets Media Level Opportunities Video Spot Video Platforms and all Outreach (10 sec) Marketing Materials Title $10,000 Lead Sponsor 30 Seconds Unlimited Sponsorship Gold Spotlight $7,500 Activity Room 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Activity Room Gold Spotlight Centenninal Prize $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Package Activity Room Gold Spotlight $7,500 Mirror Mirror 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Room Gold Spotlight $7,500 Women Who Run 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Room Gold Spotlight Show Me the $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Money Room General Chat Silver $5,000 15 Seconds Unlimited Room Bronze $3,000 Logo Listing Unlimited Why Your Sponsorship Matters COVID-19 has created many challenges for our community, and women and students are particularly impacted. At the Hall, we are working diligently to ensure that our educational materials are available online while parents, students, and community members work from home and that our work remains relevant to the times. We are moving forward to offer even more programs that support our community’s educational needs, from collaborating with our Partners to offer virtual educational events like at-home STEM workshops, to our new webinar series, “A Conversation Between”, which creates a forum for women to discuss issues that matter to them with leaders in our community. -

FINAL DRAFT SPRING 2015 Volume 19, Issue 1.Pub

Spring 2015 Volume 19, Issue 1 The WIHS Woman The Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study Visit 42 Parenthood, Golden Gate and Congregations Organizing for Renewal. After a few years of Happy Spring! working at non-profit organizations, she began working in public health research. Jenna has worked on a number of studies with UC Davis It’s hard to believe we will begin Visit 42 in Medical Center, Public Health Institute (PHI) April. We don’t have much in the way of and Kaiser Permanente. changes for this visit, but we want to keep you informed of recent WIHS activities. In 2008, she founded a grassroots organization – Red, Bike and Green – in an effort to use bicy- cling as a way to promote healthy living within Introducing Jenna Burton, the African American community. She has Clinical Research Coordinator organized tons of community bike rides, and in 2009 rode her bike from San Francisco to Los Our newest Interviewer, Jenna Burton, joined Angeles as a participant in the AIDS LifeCycle. WIHS in February 2015. In addition to doing interviews and core visits, Jenna is our new Jenna is very excited to join the WIHS com- CAB Coordinator. We are planning to have our munity and looks forward to getting to know next CAB meeting in May. We hope you can everyone. Welcome Jenna! attend, meet Jenna, and get involved with the CAB. Jenna has a BA in Anthropology from Howard University. With an interest in community health, she started doing community-based work for organizations like Planned TABLE OF CONTENTS Visit 42 ...............................................................................................................................