Frank Hamilton Cushing: Pioneer Americanist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015–2016 Annual Report

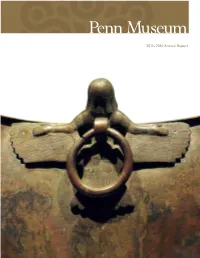

2015–2016 Annual Report 2015–2016 Annual Report 3 EXECUTIVE MESSAGE 4 THE NEW PENN MUSEUM 7 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE GEOGRAPHY 8 Teaching & Research: Penn Museum-Sponsored Field Projects 10 Excavations at Anubis-Mountain, South Abydos (Egypt) 12 Gordion Archaeological Project (Turkey) — Historical Landscape Preservation at Gordion — Gordion Cultural Heritage Education Project 16 The Penn Cultural Heritage Center — Conflict Culture Research Network (Global) — Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria & Iraq Project (Syria and Iraq) — Tihosuco Heritage Preservation & Community Development Project (Mexico) — Wayka Heritage Project (California, USA) 20 Pelekita Cave in Eastern Crete (Greece) 21 Late Pleistocene Pyrotechnology (France) 22 The Life & Times of Emma Allison (Canada) 23 On the Wampum Trail (North America) 24 Louis Shotridge & the Penn Museum (Alaska, USA) 25 Smith Creek Archaeological Project (Mississippi, USA) 26 Silver Reef Project (Utah, USA) 26 South Jersey (Vineland) Project (New Jersey, USA) 27 Collections: New Acquisitions 31 Collections: Outgoing Loans & Traveling Exhibitions 35 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE NUMBERS 40 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE MONTH 57 SUPPORTING THE MISSION 58 Leadership Supporters 62 Loren Eiseley Society 64 Expedition Circle 66 The Annual Fund 67 Sara Yorke Stevenson Legacy Circle 68 Corporate, Foundation, & Government Agency Supporters Objects on the cover, inside cover, and above were featured 71 THE GIFT OF TIME in the special exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas, from 72 Exhibition Advisors & Contributors February 13, 2016 through November 27, 2016. 74 Penn Museum Volunteers On the cover: Bronze cauldron with siren and demon 76 Board of Overseers attachments. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations 18516. -

2017 Fernald Caroline Dissert

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE VISUALIZATION OF THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST: ETHNOGRAPHY, TOURISM, AND AMERICAN INDIAN SOUVENIR ARTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CAROLINE JEAN FERNALD Norman, Oklahoma 2017 THE VISUALIZATION OF THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST: ETHNOGRAPHY, TOURISM, AND AMERICAN INDIAN SOUVENIR ARTS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS BY ______________________________ Dr. W. Jackson Rushing, III, Chair ______________________________ Mr. B. Byron Price ______________________________ Dr. Alison Fields ______________________________ Dr. Kenneth Haltman ______________________________ Dr. David Wrobel © Copyright by CAROLINE JEAN FERNALD 2017 All Rights Reserved. For James Hagerty Acknowledgements I wish to extend my most sincere appreciation to my dissertation committee. Your influence on my work is, perhaps, apparent, but I am truly grateful for the guidance you have provided over the years. Your patience and support while I balanced the weight of a museum career and the completion of my dissertation meant the world! I would certainly be remiss to not thank the staff, trustees, and volunteers at the Millicent Rogers Museum for bearing with me while I finalized my degree. Your kind words, enthusiasm, and encouragement were greatly appreciated. I know I looked dreadfully tired in the weeks prior to the completion of my dissertation and I thank you for not mentioning it. The Couse Foundation, the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center, and the School of Visual Arts, likewise, deserve a heartfelt thank you for introducing me to the wonderful world of Taos and supporting my research. A very special thank you is needed for Ginnie and Ernie Leavitt, Carl Jones, and Byron Price. -

Body of Pennsylvania, the Atwater-Kent Museum, the Museum

REVIEWS 239 Philadelphia and the Development of papers offers an important and coherent account Americanist Archaeology of one major American city’s contributions to Don D. Fowler and David R. Wilcox the intellectual development of archaeology as a learned profession in the Americas. (editors) Curtis M. Hinsley’s sweeping and finely University of Alabama Press, crafted contribution leads off the volume with Tuscaloosa, 2003. xx+246 pp., 13 an insightful analysis of Philadelphia’s late-19th illus. $65.00 cloth. century social milieu that set the city apart from Boston, New York, and other eastern cities as Being a native Philadelphian, I had the good a center of intellectual foment. Hinsley sagely fortune early on to come under the infl uence observes that it was Philadelphia’s late-19th- of the cultural opportunities offered by the city. century atmosphere of “business aristocracy” Many of Philadelphia’s venerable institutions and genteel wealth that ultimately created the were routinely on my family’s list of places climate that allowed for the leaders of the to visit when going “into town,” including the city’s institutions to become some of the coun- Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, the try’s prime players in the developing fi eld of Philadelphia Academy of Music, the Franklin archaeology. Presaging some of the later chap- Institute, the Philadelphia Art Museum, and the ters in the volume, Hinsley identifi es these key University Museum of the University of Penn- players as Daniel G. Brinton, Sara Stevenson, sylvania. In my career, I soon became aware of Stewart Culin, Charles C. -

Photography and the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, 1870•Fi1930

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 84 Number 2 Article 2 4-1-2009 Photography and the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, 1870–1930 Richard H. Frost Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Frost, Richard H.. "Photography and the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, 1870–1930." New Mexico Historical Review 84, 2 (2009). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol84/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Photography and the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, 1870-1930 Richard H. Frost hotography has influenced the relationship of Pueblo Indians and PAnglos in New Mexico since the nineteenth century. For the most part, picture-taking in the pueblos has been overshadowed by dominant issues, such as those involving land title, water rights, education, health, and sover eignty. However, the subject of photographing the Pueblos is inherently interesting, and reveals a dimension of white-Indian contacts and insights that is external to and in some respects at variance with the Anglo-Pueblo relationship on the larger issues. Photography in the pueblos usually did not involve federal government policy or authority, but it was often a source of tension between Pueblo and Anglo cultures. The tension surfaced be tween visitors and Indians without government interference. Photography has long been integrated into Pueblo ethnology, both schol arly and popular. -

Zuni Vocabulary MS.873

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8br8tc3 No online items Finding Aid to Zuni Vocabulary MS.873 Finding aid prepared by Holly Rose Larson Autry National Center, Braun Research Library 234 Museum Drive Los Angeles, CA, 90065-5030 323-221-2164 [email protected] 2012 December 13 Finding Aid to Zuni Vocabulary MS.873 1 MS.873 Title: Zuni Vocabulary Identifier/Call Number: MS.873 Contributing Institution: Autry National Center, Braun Research Library Language of Material: English Physical Description: 0.1 linear feet(1 folder) Date: 1903 Abstract: This is a bound journal with the title "Zuni Vocabulary" by Matilda Coxe Stevenson, 1903. Vocabularly is listed in alphabetical divisions by English word or phrase with Zuni equivalent. Language: English, Zuni. creator: Stevenson, Matilda Coxe, 1850-1915 Scope and Contents This is a bound journal with the title "Zuni Vocabulary" by Matilda Coxe Stevenson, 1903. Vocabularly is listed in English with Zuni equivalent. Text is divided with alphabetical tabs; entries are made in pencil and ink. End papers include a pencil sketch of a groundplan. Preferred citation Zuni Vocabulary, 1903, Braun Research Library Collection, Autry National Center, Los Angeles; MS.873. Processing history Processed by Library staff before 1981. Finding aid completed by Holly Rose Larson, NHPRC Processing Archivist, 2012 December 13, made possible through grant funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commissions (NHPRC). Acquisition Donated by Michael Harrison, 1948 December. Use Copyright has not been assigned to the Autry National Center. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Autry Archivist. -

Frederick Webb Hodge Papers, 1894-1957

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf7g50085c No online items Finding Aid for the Frederick Webb Hodge Papers, 1894-1957 Processed by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Frederick 181 1 Webb Hodge Papers, 1894-1957 Descriptive Summary Title: Frederick Webb Hodge Papers, Date (inclusive): 1894-1957 Collection number: 181 Creator: Hodge, Frederick Webb, 1864-1956 Extent: 1 box (0.5 linear ft.) Abstract: Frederick Webb Hodge (1864-1956) worked for the U.S. Geological Survey and the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE), edited the Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, was the editor of the The American Anthropologist, co-founder and president of the American Anthropological Association (AAA), director of the Museum of the American Indian, and director of the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles. The collection consists of correspondence, photographs, and printed materials related to Hodge's career as an anthropologist, historian and museum director. Language: English Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. -

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES in the HISTORY of ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O. Murray Cultural Negotiations The Role of Women in the Founding of Americanist Archaeology DAVID L. BROWMAN University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London © 2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Browman, David L. Cultural negotiations: the role of women in the founding of Americanist archaeology / David L. Browman. pages cm.— (Critical studies in the history of anthropology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8032-4381-1 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. Women archaeologists—Biography. 2. Archaeology—United States—History. 3. Women archaeologists—History. 4. Archaeologists—Biography. I. Title. CC110.B76 2013 930.1092'2—dc23 2012049313 Set in Lyon by Laura Wellington. Designed by Nathan Putens. Contents Series Editors’ Introduction vii Introduction 1 1. Women of the Period 1865 to 1900 35 2. New Directions in the Period 1900 to 1920 73 3. Women Entering the Field during the “Roaring Twenties” 95 4. Women Entering Archaeology, 1930 to 1940 149 Concluding Remarks 251 References 277 Index 325 Series Editors’ Introduction REGNA DARNELL AND STEPHEN O. MURRAY David Browman has produced an invaluable reference work for prac- titioners of contemporary Americanist archaeology who are interested in documenting the largely unrecognized contribution of generations of women to its development. Meticulous examination of the archaeo- logical literature, especially footnotes and acknowledgments, and the archival records of major universities, museums, field school programs, expeditions, and general anthropological archives reveals a complex story of marginalization and professional invisibility, albeit one that will be surprising neither to feminist scholars nor to female archaeologists. -

MS 4372 Miscellaneous Material Relating to the History of the Bureau of American Ethnology, the History of Anthropology, and Anthropological Controversies

MS 4372 Miscellaneous material relating to the history of the Bureau of American Ethnology, the history of anthropology, and anthropological controversies National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland, Maryland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Local Numbers................................................................................................................. 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 MS 4372 Miscellaneous material relating to the history of the Bureau of American Ethnology, the history of anthropology, and anthropological controversies NAA.MS4372 Collection Overview Repository: National Anthropological Archives Title: MS 4372 Miscellaneous material relating to the history of the Bureau of American Ethnology, the history of anthropology, and anthropological controversies Identifier: NAA.MS4372 Date: undated Creator: Stirling, Matthew Williams, 1896-1975 (Collector) Language: Undetermined . Administrative Information Provenance Sent to the BAE archives by M. W. Stirling, Director, January, 1951. Citation Manuscript 4372, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution Local Numbers NAA MS -

Frank Hamilton Cushing by Guy Belleranti

Name : Frank Hamilton Cushing by Guy Belleranti Frank Hamilton Cushing was a pioneer anthropologist. Born in Pennsylvania in 1857, Cushing was a white man who studied Native Americans as no one had before. He actually lived among the Zuni Tribe of New Mexico for several years. While doing so, he adopted their customs and learned their ways. In fact, he was one of the !rst professional anthropologists to live with the people he was studying.PREVIEW Cushing seemed to be born into a career in anthropology, the science that deals Gain complete access to the largest with the study of the origins and development of cultures among di"erent groups of collection of worksheets in all subjects! people. He showed a interest in the !eld as a young boy, collecting relics and fossils while he was eight. Not a member? Members, please log in to Please sign up to When he was 13, his family moved to Newgain York. This move opened new worlds for download this complete access. him to explore. He wanderedworksheet. the forests near his home. He became fascinated with the Indian artifacts he found. Cushing’s interest became so great he even taught himself to reproduce arrowheads and otherwww.mathworksheets4kids.com artifacts by processes similar to those of the natives. By the time Cushing was 17 he had published his !rst scienti!c paper. He followed this up with a brief enrollment as a student at Cornell University. More knowledgeable than his instructors, he became curator of an exhibition of Indian artifacts. Not long after this, the director of the Smithsonian Institution made a 19-year-old Cushing curator of the Ethnological Department at the National Museum in Washington, D.C. -

Bibliographies of Northern and Central California Indians. Volume 3--General Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 370 605 IR 055 088 AUTHOR Brandt, Randal S.; Davis-Kimball, Jeannine TITLE Bibliographies of Northern and Central California Indians. Volume 3--General Bibliography. INSTITUTION California State Library, Sacramento.; California Univ., Berkeley. California Indian Library Collections. St'ONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. Office of Library Programs. REPORT NO ISBN-0-929722-78-7 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 251p.; For related documents, see ED 368 353-355 and IR 055 086-087. AVAILABLE FROMCalifornia State Library Foundation, 1225 8th Street, Suite 345, Sacramento, CA 95814 (softcover, ISBN-0-929722-79-5: $35 per volume, $95 for set of 3 volumes; hardcover, ISBN-0-929722-78-7: $140 for set of 3 volumes). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian History; *American Indians; Annotated Bibliographies; Films; *Library Collections; Maps; Photographs; Public Libraries; *Resource Materials; State Libraries; State Programs IDENTIFIERS *California; Unpublished Materials ABSTRACT This document is the third of a three-volume set made up of bibliographic citations to published texts, unpublished manuscripts, photographs, sound recordings, motion pictures, and maps concerning Native American tribal groups that inhabit, or have traditionally inhabited, northern and central California. This volume comprises the general bibliography, which contains over 3,600 entries encompassing all materials in the tribal bibliographies which make up the first two volumes, materials not specific to any one tribal group, and supplemental materials concerning southern California native peoples. (MES) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** U.S. -

Reflections on Frederick Webb Hodge, 1864-1956

History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 32 Issue 2 December 2005 Article 3 January 2005 Anthropology's Organization Man: Reflections on rF ederick Webb Hodge, 1864-1956 Curtis M. Hinsley Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Hinsley, Curtis M. Jr. (2005) "Anthropology's Organization Man: Reflections on rF ederick Webb Hodge, 1864-1956," History of Anthropology Newsletter: Vol. 32 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol32/iss2/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol32/iss2/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANTHROPOLOGY'S ORGANIZATION MAN: REFLECfiONS ON FREDERICK WEBB HODGE, 1864-1956 Curtis Hinsley Northern Arizona University "Terrible nightmare. Were the oysters to blame? Falling over precipices and facing revolvers all night and holhwing to the top of my voice (at least so the porter tells me)."l Thus 22-year-old Frederick Webb Hodge recorded the night of December 5, 1886, on the train from Baltimore to Rochester to meet up with Frank Hamilton Cushing for the first time. The next day he traveled on to the Cushing family homestead in Albion, on the western edge of New York, where he met Cushing and his wife Emily, her sister Maggie Magill, and three Zuni Indians. Less than a week later, Cushing's enterprise, the "Hemenway Southwestern Archaeological Expedition," departed from Albion for Arizona Territory, with Hodge employed as Cushing's personal secretary. Although he had no way of knowing it at the time, the Hemenway Expedition of the next three years was to become Hodge's introduction to anthropological fieldwork and the American Southwest, as well as the foundation of a long life at the institutional center of twentieth-century American anthropology. -

Sara Yorke Stevenson Papers

Sara Yorke Stevenson Papers Sara Yorke Stevenson (1847-1921), archeologist, Egyptologist, civic leader, newspaper editor and columnist, was one of the principal founders of what is now called the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology; In 1894 she became the first woman to receive an honorary degree from Penn. Stevenson served as Curator of the Egyptian and Mediterranean Section and member of the Museum’s governing board from 1890 to 1905, but she resigned in 1905––apparently over the Board’s handling of disputes about Hermann Hilprecht, Curator of the Babylonian Section. Founder and first president of the Equal Franchise Society, co-founder and two- term president of the Civic Club (a women’s group pushing for reform and civic improvement), chair of the French War Relief Committee of the Emergency Aid of Pennsylvania, Stevenson played a leadership role in many of Philadelphia’s “good causes.” For more than a decade she was also literary editor and columnist for the Philadelphia Public Ledger, writing under the pen names “Peggy Shippen” and “Sallie Wistar.” These papers (1.8 cubic feet), removed in 2006 from a home once lived in by Stevenson’s friend Frances Anne Wister (1874-1956), cover the full range of Stevenson’s interests. Highlights include her newspaper clippings and comments on the Hilprecht dispute, copies of hundreds of letters to her from her good friend William Pepper, Jr. (1898; provost at Penn, civic leader), and letters to her from many other Philadelphia notables. Donation of David Prince Estate