A Brief History of the Penn Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015–2016 Annual Report

2015–2016 Annual Report 2015–2016 Annual Report 3 EXECUTIVE MESSAGE 4 THE NEW PENN MUSEUM 7 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE GEOGRAPHY 8 Teaching & Research: Penn Museum-Sponsored Field Projects 10 Excavations at Anubis-Mountain, South Abydos (Egypt) 12 Gordion Archaeological Project (Turkey) — Historical Landscape Preservation at Gordion — Gordion Cultural Heritage Education Project 16 The Penn Cultural Heritage Center — Conflict Culture Research Network (Global) — Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria & Iraq Project (Syria and Iraq) — Tihosuco Heritage Preservation & Community Development Project (Mexico) — Wayka Heritage Project (California, USA) 20 Pelekita Cave in Eastern Crete (Greece) 21 Late Pleistocene Pyrotechnology (France) 22 The Life & Times of Emma Allison (Canada) 23 On the Wampum Trail (North America) 24 Louis Shotridge & the Penn Museum (Alaska, USA) 25 Smith Creek Archaeological Project (Mississippi, USA) 26 Silver Reef Project (Utah, USA) 26 South Jersey (Vineland) Project (New Jersey, USA) 27 Collections: New Acquisitions 31 Collections: Outgoing Loans & Traveling Exhibitions 35 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE NUMBERS 40 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE MONTH 57 SUPPORTING THE MISSION 58 Leadership Supporters 62 Loren Eiseley Society 64 Expedition Circle 66 The Annual Fund 67 Sara Yorke Stevenson Legacy Circle 68 Corporate, Foundation, & Government Agency Supporters Objects on the cover, inside cover, and above were featured 71 THE GIFT OF TIME in the special exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas, from 72 Exhibition Advisors & Contributors February 13, 2016 through November 27, 2016. 74 Penn Museum Volunteers On the cover: Bronze cauldron with siren and demon 76 Board of Overseers attachments. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations 18516. -

Benin Kingdom • Year 5

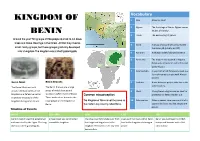

BENIN KINGDOM REACH OUT YEAR 5 name: class: Knowledge Organiser • Benin Kingdom • Year 5 Vocabulary Oba A king, or chief. Timeline of Events Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means 900 CE Lots of villages join together and make a “Rulers of the Sky”. kingdom known as Igodomigodo, ruled by Empire lots of countries or states, all ruled by the Ogiso. one monarch or single state. c. 900- A huge earthen moat was constructed Guild A group of people who all do the 1460 CE around the kingdom, stretching 16.000 km same job, usually a craft. long. Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 1180 CE The Oba royal family take over from the Voodoo The belief that non-human objects Osigo, and begin to rule the kingdom. (or Vodun) have spirits or souls. They are treated like Gods. Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as 1440 CE Benin expands its territory under the rule of Oba Ewuare the Great. a kind of money to trade with African leaders. 1470 CE Oba Ewuare renames the kingdom as Civil war A war between people who live in the Edo, with it;s main city known as Ubinu (Benin in Portuguese). same country. Moat A long trench dug around an area to 1485 CE The Portuguese visit Edo and Ubinu. keep invaders out. 1514 CE Oba Esigie sets up trading links with the Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Portuguese, and other European visitors. country by force, and live among the 1700 CE A series of civil wars within Benin lead to people. -

BRITISH SCHOOL of ARCHAEOLOGY in IRAQ (Gertrude Bell Memorial)

BRITISH SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN IRAQ (Gertrude Bell Memorial) REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30th JUNE Printed by 1938 Cheltenham Press Ltd., Cheltenham and London. THE SIXTH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE SCHOOL WILL BE HELD IN THE HALL OF THE ROYAL SOCrETY, BURLI NGTON HOUSE, ON WEDNESDAY, 1 OCTOBER 19TH, 1938, AT 5.30 O'CLOCK, TO CONSIDER THE ACCOUNTS, BALANCE SHEET AND REPORTS OF THE COUNCIL AND AUDITOR ; TO ELECT MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL ; TO APPOINT AN AUDITOR ; AND FOR ANY OTHER BUSINESS WHICH MAY PROPERLY BE TRANSACTED. PRESIDENT COUNCIL RIGHT HON. L. S. AMERY, M.P. LIFE M E M BERS SIR CHARLES HYDE, DART., LL.D. WILLIA.\\1 RUSHTON PARKER, M.D. MRS. W I LLIAM H . MOORE *LADY RICHMOND VICE- PRESIDENTS GEORGE LOWTHIAN T REVELYAN HIS GRACE THE ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY SIR MAURICE PETERSON , K.C.M.G. NOMI NATED MEMBERS REPRESENTING : P l!OFESSOR VERE GORDON CHILDE, F .S.A. Edinburgh Unive rsity MISS A. M . DALE Lad y Margaret Hall, Oxford FOUNDERS *G. R. DRIVER, M.G. Magdalen College, Oxford SIR CHARLES HYDE, BART., LL.D. *PROFESSOR S. R. K . GLA:"!V!LLE, F .S.A. Bo,ilrd of Studie s in Archaeol ogy, London Universi ty MRS. WILLIAM H. MOORE ADMIRAL SIR WILLIAM GOODENOUGH , G.C.B ., M .V.O., Royal Geographical Society *SIR GEORGE F . H ILL , K.C.B., D.C.L., LITT.D., LL.D., F .B.A., F .S.A., British Academy CHAIRMAN OF EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE SIR FREDERIC G. KENYON, G .B.E., K.C.B., T.D. -

New Vice President Finance & Treasurer $6.5 Million for Center Of

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday, January 11, 2000 Volume 46 Number 16 www.upenn.edu/almanac/ Professor Farber to FCC New Vice President Finance & Treasurer Internet pioneer Craig Carnaroli, director of the Health Care Finance Department at Merrill David Farber, the Lynch & Co., has been named Vice President for Finance and Treasurer at Alfred Fitler Moore Penn by Executive Vice President John A. Fry. Professor of Tele- As Vice President for Finance and Treasurer, Mr. Carnaroli is responsible communication for the University’s financial planning processes and coordinates the finan- Systems, has been cial activities for the University and its component parts. He is directly re- named Chief Tech- sponsible for the offices of the Comptroller, Treasurer, Investments, Student nologist for the Fed- Financial Services, Risk Management, Research Services and Acquisition eral Communica- Services. tions Commission “Craig is an outstanding financial executive, who has spent his entire (FCC). He will be career in public finance investment banking, working primarily with hospi- on leave while in tals and colleges and universities,” said Mr. Fry. “His expertise in these areas the government ser- will enable him to lead the Division of Finance forward in a strategic and Craig Carnaroli vice in Washington. progressive manner, as well as enable him to play a key role in planning financial strategies for the The position is tra- University and the Health System.” ditionally a one- or Mr. Carnaroli joined Merrill Lynch in 1995, where he led a team of professionals responsible two-year appoint- for structuring and marketing tax-exempt and taxable debt issues for non-profit education and David Farber ment held by a healthcare institutions. -

Guide, Office of the Provost Records. William Pepper Administration

A Guide to the Office of the Provost Records. William Pepper Administration 1887-1892 0.25 Cubic feet UPA 6.2Pep Prepared by Edward A. Skuchas under the direction of J.M. Duffin 2002 The University Archives and Records Center 3401 Market Street, Suite 210 Philadelphia, PA 19104-3358 215.898.7024 Fax: 215.573.2036 www.archives.upenn.edu Mark Frazier Lloyd, Director Office of the Provost Records. William Pepper Administration UPA 6.2Pep TABLE OF CONTENTS PROVENANCE...............................................................................................................................1 ARRANGEMENT...........................................................................................................................1 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE................................................................................................................1 SCOPE AND CONTENT...............................................................................................................3 CONTROLLED ACCESS HEADINGS.........................................................................................3 INVENTORY.................................................................................................................................. 4 CORRESPONDENCE...............................................................................................................4 Office of the Provost Records. William Pepper Administration UPA 6.2Pep Guide to the Office of the Provost Records. William Pepper Administration 1887-1892 UPA 6.2Pep 0.25 Cubic feet -

Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: a Biographical and Contextual View Karen L

Andean Past Volume 7 Article 14 2005 Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View Karen L. Mohr Chavez deceased Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Mohr Chavez, Karen L. (2005) "Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View," Andean Past: Vol. 7 , Article 14. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol7/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALFRED KIDDER II IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY: A BIOGRAPHICAL AND CONTEXTUAL VIEW KAREN L. MOHR CHÁVEZ late of Central Michigan University (died August 25, 2001) Dedicated with love to my parents, Clifford F. L. Mohr and Grace R. Mohr, and to my mother-in-law, Martha Farfán de Chávez, and to the memory of my father-in-law, Manuel Chávez Ballón. INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY SERGIO J. CHÁVEZ1 corroborate crucial information with Karen’s notes and Kidder’s archive. Karen’s initial motivation to write this biography stemmed from the fact that she was one of Alfred INTRODUCTION Kidder II’s closest students at the University of Pennsylvania. He served as her main M.A. thesis This article is a biography of archaeologist Alfred and Ph.D. dissertation advisor and provided all Kidder II (1911-1984; Figure 1), a prominent necessary assistance, support, and guidance. -

A Spatial Analysis of Ceramics in Northwestern Alaska: Studying Pre-Contact Gendered Use of Space

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Winter 3-14-2018 A Spatial Analysis of Ceramics in Northwestern Alaska: Studying Pre-Contact Gendered Use of Space Katelyn Elizabeth Braymer-Hayes Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Anthropology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Braymer-Hayes, Katelyn Elizabeth, "A Spatial Analysis of Ceramics in Northwestern Alaska: Studying Pre- Contact Gendered Use of Space" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4357. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6250 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Spatial Analysis of Ceramics in Northwestern Alaska: Studying Pre-Contact Gendered Use of Space by Katelyn Elizabeth Braymer-Hayes A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Anthropology Thesis Committee: Shelby L. Anderson, Chair Virginia L. Butler Douglas C. Wilson Portland State University 2018 Abstract Activities and production among ethnographic Arctic peoples were primarily divided by gender. This gendered division of labor also extended to a spatial segregated pattern of the household in some Arctic cultures. Other cultures had a more gender-integrated spatial pattern of the household. There have been very few archaeological studies of gender in the Arctic, and even fewer studies of gendered use of space. In this thesis, I evaluated the existence of this gendered use of space in pre-contact Northwest Alaska. -

The Cinchona Program (1940-1945): Science and Imperialism in the Exploitation of a Medicinal Plant

The Cinchona Program (1940-1945): science and imperialism in the exploitation of a medicinal plant Nicolás Cuvi (*) (*) Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO-Ecuador; Centre d’Història de la Ciència, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. [email protected] Dynamis Fecha de recepción: 25 de enero de 2010 [0211-9536] 2011; 31 (1): 183-206 Fecha de aceptación: 27 de julio de 2010 SUMARIO: 1.—Introduction. 2.—Cinchona and its alkaloids. 3.—The War and the need for raw materials. 4.—The quest for Cinchona in the Andes. 5.—Extraction and sale of Cinchona. 6.—Nur- series, plantations and alkaloids factories. 7.—The end of the Cinchona Program. 8.—Epilogue. ABSTRACT: During World War II, the United States implemented programs to exploit hundreds of raw materials in Latin America, many of them botanical. This required the participation of the country’s scientific community and marked the beginning of intervention in Latin Ame- rican countries characterized by the active participation of the United States in negotiations (and not only by private firms supported by the United States). Many federal institutions and companies were created, others were adapted, and universities, research centers and pharma- ceutical companies were contracted. The programs undertaken by this coalition of institutions served to build and consolidate the dependence of Latin American countries on United States technology, to focus their economies on the extraction and development of resources that the United States could not obtain at home (known as «complementary») and to impede the development of competition. Latin American republics had been historically dependant on raw material exports (minerals and plants). -

Sir Leonard Woolley

204 OBITUARIES devoted to his students that his output of publications was com- paratively small. Had he survived, many more important mono- graphs would have come from his pen. His grateful students will bring to fruition some of the works which he projected but was unable to finish. JOHN W. SPELLMAN. SIR LEONARD WOOLLEY Charles Leonard Woolley, who died on 20th February, 1960, nearly eighty years old, had not only a diversity of archaeological experience unequalled in his generation, but also gifts that helped to make his opportunities and turned them to unique account. After he had had a short museum experience in Oxford, the pattern of his life was quickly set by some minor explorations in Nubia : he was to be the field-archaeologist, not the academic scholar, still less the teacher. Three sites in the Near East were the scenes of Woolley's most memorable achievements. Two of these, Ur and Carchemish, had already been identified and partly worked ; the third, 'Atshanah, was his own discovery. Its neighbourhood abounds in ancient mounds, and Woolley's choice of one among them all was brilliantly justified when it proved to be Alalakh, a place of no little note in the international politics of the later second millennium B.C. Carchemish gave him his introduction to the Near East and yielded to his work a series of late Hittite sculptures and inscriptions and the most comprehensive plan of the city's fortifications. But his most famous discoveries were made in thirteen seasons at the ancient city of Ur in Southern Iraq. -

What Was Life Like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’S Enquiry: Why Is It Important to Learn About Benin in School?

History Our main enquiry question this term: What was life like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’s enquiry: Why is it important to learn about Benin in school? Benin Where is Benin? Benin is a region in Nigeria, West Africa. Benin was once a civilisation of cities and towns, powerful Kings and a large empire which traded over long distances. The Benin Empire 900-1897 Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. As their kingdom expanded they built walls and moats around Benin City which showed incredible town planning and architecture. What do you think of Benin City? Benin craftsmen were skilful in Bronze and Ivory and had strong religious beliefs. During this time, West Africa invented the smelting (heating and melting) of copper and zinc ores and the casting of Bronze. What do you think that this might mean? Why might this be important? What might this invention allowed them to do? This allowed them to produced beautiful works of art, particularly bronze sculptures, which they are famous for. Watch this video to learn more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zpvckqt/articles/z84fvcw 7 Benin was the center of trade. Europeans tried to trade with Benin in the 15 and 16 century, especially for spices like black pepper. When the Europeans arrived 8 Benin’s society was so advanced in what they produced compared with Britain at the time. -

January 1968

Luce, Harris Named Faculty, Administration Give University Professors Two faculty members were named $3 Million to University Professors by the Board of Capital Campaign Trustees during their meeting last A total of 1,630 faculty and staff the country couldn't ask for a more month. They are Dr. Robert Duncan members of the University of Pennsyl- heartwarming vote of encouragement." Luce, professor of psychology, and Dr. vania have given $3,288,682 anony- It is hoped that by the May Trustees Zellig Harris, professor of linguistics. mously to its Development Program, meeting, at least 75 percent of the faculty University professorships were estab- Wilfred D. Gillen, chairman of the and staff will have participated. lished at Pennsylvania in 1961 to honor University's trustees, announced in Leading the appeal among the aca- those faculty members who are particu- December. demic faculties is Dr. George 'W. Taylor, larly distinguished in scholarship and It is believed that this is the larg- Harnwell Professor of Industry and whose contributions to knowledge have est amount ever contributed by any noted labor mediator; among the medical been made in more than one discipline, faculty and administration to a campaign faculties, Dr. Richard H. Chamberlain, rather than in a narrow field of speciali- of this kind. Over 50 percent have con- chairman of the Radiology Department zation. Dr. Luce and Dr. Harris are the tributed to the campaign. in the School of Medicine; and among eighth and ninth scholars to be named Gillen said the faculty-staff gifts had the administrative staff, Dr. Donald S. -

Kingdom of Benin Is Not the Same As 10 Colonisation When Invaders Take Over Control of a Benin

KINGDOM OF Vocabulary 1 Oba A king or chief. 2 Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means BENIN ‘Rulers of the Sky’. 3 Trade The exchanging of goods. Around the year 900 groups of Edo people started to cut down trees and make clearings in the forest. At first they lived in 4 Guild A group of people who all complete small family groups, but these groups gradually developed the same job (usually a craft). into a kingdom. The kingdom was called Igodomigodo. 5 Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 6 Benin city The modern city located in Nigeria. Previously, it has been called Edo and Igodomigodo. 7 Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as a form of money to trade with African leaders. Benin Moat Benin Bronzes 8 Civil war A war between people who live in the same country. The Benin Moat was built The Benin Bronzes are a large around the boundaries of the group of metal plaques and 9 Moat A long trench dug around an area for kingdom as a defensive barrier sculptures (often made of brass). Common misconception protection to keep invaders out. to protect the people of the These works of art decorate the kingdom during times of war. royal palace of the Kingdom of The Kingdom of Benin is not the same as 10 Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Benin. the modern day country called Benin. country by force, and live among the people. Timeline of Events 900 AD 900—1460 1180 1700 1897 Benin Kingdom was first established A huge moat was constructed The Oba royal family take over from A series of civil wars within Benin Benin was destroyed by British and was ruled by the Ogiso.